BUDGET STRATEGY AND OUTLOOK

BUDGET PAPER NO. 1

Circulated by

The Honourable Jim Chalmers MP

Treasurer of the Commonwealth of Australia

and

Senator the Honourable Katy Gallagher

Minister for Finance, Minister for Women,

Minister for the Public Service of the Commonwealth of Australia

For the information of honourable members

on the occasion of the Budget 2024–25

14 May 2024

© Commonwealth of Australia 2024

ISSN 0728 7194 (print); 1326 4133 (online)

This publication is available for your use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

International licence, with the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, third-party

content and where otherwise stated. The full licence terms are available from

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode.

Use of Commonwealth of Australia material under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

International licence requires you to attribute the work (but not in any way that suggests that

the Commonwealth of Australia endorses you or your use of the work).

Commonwealth of Australia material used ‘as supplied’.

Provided you have not modified or transformed Commonwealth of Australia material in any

way including, for example, by changing the Commonwealth of Australia text; calculating

percentage changes; graphing or charting data; or deriving new statistics from published

statistics – then the Commonwealth of Australia prefers the following attribution:

Source: The Commonwealth of Australia.

Derivative material

If you have modified or transformed Commonwealth of Australia material, or derived new

material from those of the Commonwealth of Australia in any way, then the Commonwealth

of Australia prefers the following attribution:

Based on Commonwealth of Australia data.

Use of the Coat of Arms

The terms under which the Coat of Arms can be used are set out on

the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet website (see www.pmc.gov.au/

honours-and-symbols/commonwealth-coat-arms).

Other uses

Enquiries regarding this licence and any other use of this document are welcome at:

Manager

Media Unit

The Treasury

Langton Crescent

Parkes ACT 2600

Email: media@treasury.gov.au

Internet

A copy of this document is available on the central Budget website at: www.budget.gov.au.

Printed by CanPrint Communications Pty Ltd

Page iii

Contents

Statement 1: Budget Overview .................................................................................... 1

Economic and Fiscal Outlook ........................................................................................................ 5

Budget priorities ............................................................................................................................ 8

Statement 2: Economic Outlook ................................................................................ 39

Outlook for the international economy......................................................................................... 43

Outlook for the domestic economy .............................................................................................. 50

Statement 3: Fiscal Strategy and Outlook ................................................................ 73

Economic and Fiscal Strategy ..................................................................................................... 79

Fiscal outlook .............................................................................................................................. 84

The Government’s balance sheet ............................................................................................. 103

Fiscal impacts of the net zero transformation ............................................................................ 107

Physical Impacts of Climate Change......................................................................................... 107

Net zero spending ..................................................................................................................... 108

New net zero spending measures ............................................................................................. 113

Appendix A: Other fiscal aggregates ......................................................................................... 116

Statement 4: Meeting Australia’s Housing Challenge ........................................... 121

Australia has underinvested in housing for too long .................................................................. 125

Affordability pressures are high ................................................................................................. 135

Barriers to the construction of new homes need to be addressed ............................................ 140

The Government’s plan to meet Australia’s housing challenge ................................................. 149

Australian Government housing measures since May 2022 ..................................................... 156

Statement 5: Revenue ............................................................................................... 163

Overview .............................................................................................................................. 167

Variations in receipts estimates ................................................................................................ 172

Variations in revenue estimates ................................................................................................ 183

Appendix A: Tax Expenditures .................................................................................................. 186

Statement 6: Expenses and Net Capital Investment ............................................. 189

Overview .............................................................................................................................. 193

Estimated expenses by function ............................................................................................... 196

General government sector expenses ...................................................................................... 200

General government net capital investment .............................................................................. 227

Appendix A: Expense by function and sub-function .................................................................. 231

Page iv

Statement 7: Debt Statement ................................................................................... 235

Australian Government Securities on issue .............................................................................. 239

Green Treasury Bonds .............................................................................................................. 244

Non-resident holdings of AGS on issue .................................................................................... 244

Net debt .............................................................................................................................. 245

Interest on AGS ........................................................................................................................ 247

Appendix A: AGS issuance ....................................................................................................... 251

Statement 8: Forecasting Performance and Sensitivity Analysis ....................... 253

Assessing past forecasting performance .................................................................................. 257

Assessing forecast uncertainty – confidence interval analysis .................................................. 265

Assessing current forecasts through sensitivity analysis........................................................... 271

Statement 9: Statement of Risks ............................................................................. 275

Risks to the Budget – Overview ................................................................................................ 279

Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry ........................................................................................... 288

Attorney-General’s .................................................................................................................... 290

Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water.............................................................. 292

Defence .............................................................................................................................. 296

Employment and Workplace Relations ..................................................................................... 299

Finance .............................................................................................................................. 301

Foreign Affairs and Trade ......................................................................................................... 305

Health and Aged Care ............................................................................................................... 307

Home Affairs ............................................................................................................................. 311

Industry, Science and Resources.............................................................................................. 314

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts ..................... 317

Prime Minister and Cabinet ....................................................................................................... 323

Social Services ......................................................................................................................... 324

Treasury .............................................................................................................................. 326

Veterans’ Affairs ........................................................................................................................ 333

Government loans ..................................................................................................................... 334

Statement 10: Australian Government Budget Financial Statements ................. 349

Appendix A: Financial reporting standards and budget concepts ............................................. 385

Appendix B: Assets and Liabilities ............................................................................................ 393

Statement 11 Historical Australian Government Data........................................... 407

Data sources ............................................................................................................................. 411

Comparability of data across years ........................................................................................... 411

Revisions to previously published data ..................................................................................... 413

Notes .......................................................................................................................... 435

Statement 1: Budget Overview | Page 1

Statement 1

Budget Overview

The 2024–25 Budget delivers cost-of-living help and builds a future made in Australia.

It helps ease the pressures people are under today, invests in a stronger and more resilient

economy and continues the Government’s record of responsible economic management.

Global uncertainty, high but moderating inflation, and higher interest rates are contributing

to cost-of-living pressures and combining to slow the economy. At the same time, the

global transformation to net zero and rapid shifts in the geostrategic landscape are creating

new opportunities and challenges for Australia’s economic prosperity and security.

While many Australians remain under pressure, Australia is better placed than most

economies to manage these challenges and become the beneficiaries of change. This Budget

strikes the right balance between keeping pressure off inflation, delivering cost-of-living

relief, supporting sustainable economic growth and strengthening public finances.

Following a surplus in 2022–23, a second is expected in 2023–24, which would be the first

back-to-back surpluses in nearly two decades. The Budget forecasts lower gross

debt-to-GDP and lower inflation, which is expected to return to the RBA’s target band

earlier than previously expected.

This Budget responds to the challenges of today and lays the foundation for future

prosperity by:

• easing cost-of-living pressures

• building more homes for Australians

• investing in a Future Made in Australia

• strengthening Medicare and the care economy

• broadening opportunity and advancing equality.

Global growth is expected to remain subdued over the next few years as the effects of high

inflation, restrictive macroeconomic policies, geopolitical tensions, and challenges in the

Chinese economy weigh on the outlook. Tackling inflation remains the primary focus but,

as inflationary pressures abate and labour markets soften, the global policy focus will

increasingly shift to managing risks to growth.

Inflation remains elevated, but has moderated to less than half of its peak in 2022. Annual

inflation has moderated more quickly than forecast at the 2023–24 Mid-Year Economic and

Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) and is expected to be lower in 2023–24. The Government’s

responsible cost-of-living relief measures of energy bill relief and Commonwealth Rent

Assistance are estimated to directly reduce headline inflation by ½ of a percentage point in

| Budget Paper No. 1

Page 2 | Statement 1: Budget Overview

2024–25 and are not expected to add to broader inflationary pressures. This could see

headline inflation return to the RBA’s target band by the end of 2024, slightly earlier than

expected at MYEFO.

The labour market has been resilient, with employment growing faster than many other

advanced economies, the unemployment rate near its 50-year historical low, nominal

wages growing at their its fastest rate in nearly 15 years and real wages now growing.

The Government delivered a $22.1 billion surplus in 2022–23. A second surplus of

$9.3 billion (0.3 per cent of GDP) is expected in 2023–24, an improvement of $10.5 billion

since MYEFO. The back-to-back surpluses reflect the Government’s discipline to return

96 per cent of tax upgrades to Budget in 2023–24 and 82 per cent of tax upgrades since the

Pre-election Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2022 (PEFO) over the forward estimates period.

A deficit of $28.3 billion is forecast in 2024–25. Over the six years to 2027–28, the underlying

cash balance is stronger in every year compared to PEFO and has improved by a

cumulative $214.7 billion. Gross debt as a share of the economy is projected to be lower

than MYEFO in every year of the forward estimates and medium term.

This Budget delivers further cost-of-living relief, with tax cuts to all 13.6 million taxpayers.

The Government’s tax changes deliver bigger tax cuts for low- and middle-income

Australians in a way that does not add to the inflation outlook. The Budget also provides

energy bill relief for all households, further increases to Commonwealth Rent Assistance,

financial support for students and cheaper medicines.

The Government is taking action to build more homes for Australians. This Budget delivers

more housing, provides additional funding for social housing and homelessness, and helps

address infrastructure bottlenecks to support the building of more homes. It also invests in

better transport in growth areas, including Western Sydney and South East Queensland.

This Budget invests in a stronger and more resilient economy by building a future made in

Australia. It reforms investment settings and approvals, and accelerates Australia’s plan to

become a renewable energy superpower by unlocking private investment in the production

of hydrogen, critical minerals, and clean manufacturing. It invests in digital and defence

priorities, supports small business and boosts engagement and trade in our region.

This Budget will reform higher education to expand access and deliver the highly skilled

workforce of the future. It invests in skills in priority industries and creates a more

integrated tertiary education system that responds and adapts to skills needs.

The Government is investing in strengthening Medicare and providing cheaper and more

accessible health care, including Medicare Urgent Care Clinics and PBS listings. The

Government continues to improve aged care, and reform the NDIS to get it back on track.

The Budget builds on the Government’s commitment to broaden opportunity and advance

equality. It includes initiatives to support gender equality, including superannuation on

Government-funded Paid Parental Leave and support for women affected by violence, and

makes investments in essential services, housing and support for First Nations Australians.

Statement 1: Budget Overview | Page 3

Statement contents

Economic and Fiscal Outlook ...................................................................................... 5

Responsible economic management ............................................................................................ 7

Budget priorities............................................................................................................ 8

Easing cost-of-living pressures ..................................................................................................... 8

Building more homes for Australians........................................................................................... 11

Investing in a Future Made in Australia ....................................................................................... 14

Strengthening Medicare and the care economy .......................................................................... 27

Broadening opportunity and advancing equality ......................................................................... 32

Measures to support economic inclusion since May 2022 .......................................................... 36

Statement 1: Budget Overview | Page 5

Statement 1: Budget Overview

Economic and Fiscal Outlook

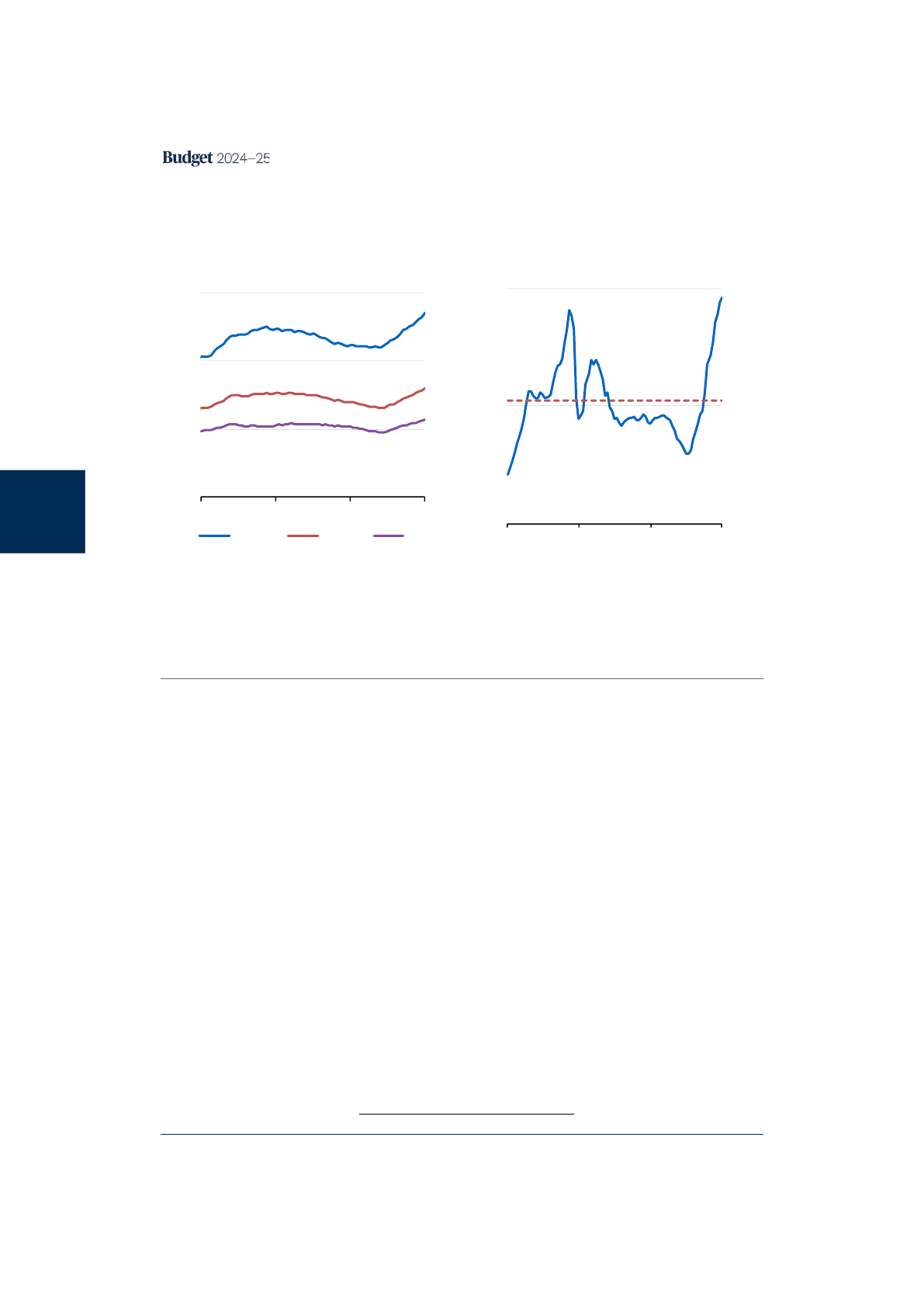

Global growth is expected to remain subdued over the next few years as the effects of high

inflation, restrictive macroeconomic policies, geopolitical tensions, and challenges in the

Chinese economy weigh on the outlook. Global growth is forecast to remain flat at around

3¼ per cent in 2024, 2025, and 2026. This would represent the longest stretch of

below-average global growth since the early 1990s. While fighting inflation remains the

primary task, as inflationary pressures abate and labour markets soften, the global policy

focus will begin to shift to managing risks to growth.

Australia is not immune from global developments and the combination of moderating but

high inflation and higher interest rates have resulted in lower growth over the past year.

Real GDP is forecast to grow by 1¾ per cent in 2023–24. The Australian economy is well

placed to navigate these economic challenges, with moderating inflation, a resilient labour

market, a return to annual real wage growth and a solid pipeline of business investment.

Although inflation remains elevated, it has moderated substantially and is now less than

half of its peak in 2022. The moderation has occurred more quickly than anticipated at

MYEFO. While there remains considerable uncertainty around the outlook for the domestic

and global economy, energy bill relief and Commonwealth Rent Assistance in this Budget

are expected to directly reduce inflation by ½ of a percentage point in 2024–25 and not

expected to add to broader inflationary pressures. This could see headline inflation return

to the target band by the end of 2024, slightly earlier than expected at MYEFO.

The labour market has been resilient. The unemployment rate is historically low, the

participation rate is near its record high and employment is growing faster than any major

advanced economy over the past year. As labour market conditions continue to ease over

2024–25, the unemployment rate is expected to rise slightly but remain below

pre-pandemic levels.

Nominal wage growth has picked up and is growing at its fastest rate in nearly 15 years.

The moderation in inflation and pick up in wage growth have contributed to an

improvement in real wages. Real wages have risen for three consecutive quarters and

returned to annual growth at the end of 2023, which is earlier than previously forecast.

Real wages are expected to rise further and grow by ½ per cent through-the-year to the

June quarter 2024.

There is a solid pipeline of business investment, with annual investment growth expected

to continue through to 2025–26. If realised, this would be the longest sustained increase in

investment since the mining boom.

| Budget Paper No. 1

Page 6 | Statement 1: Budget Overview

Growth is expected to remain subdued over the forecast period. Real GDP is forecast to

grow by 2 per cent in 2024–25, 2¼ per cent in 2025–26 and 2½ per cent in 2026–27. Higher

wages growth, the forecast moderation in inflation, continuing employment growth and

the Government’s cost-of-living tax cuts should support real household disposable incomes

and a recovery in household consumption.

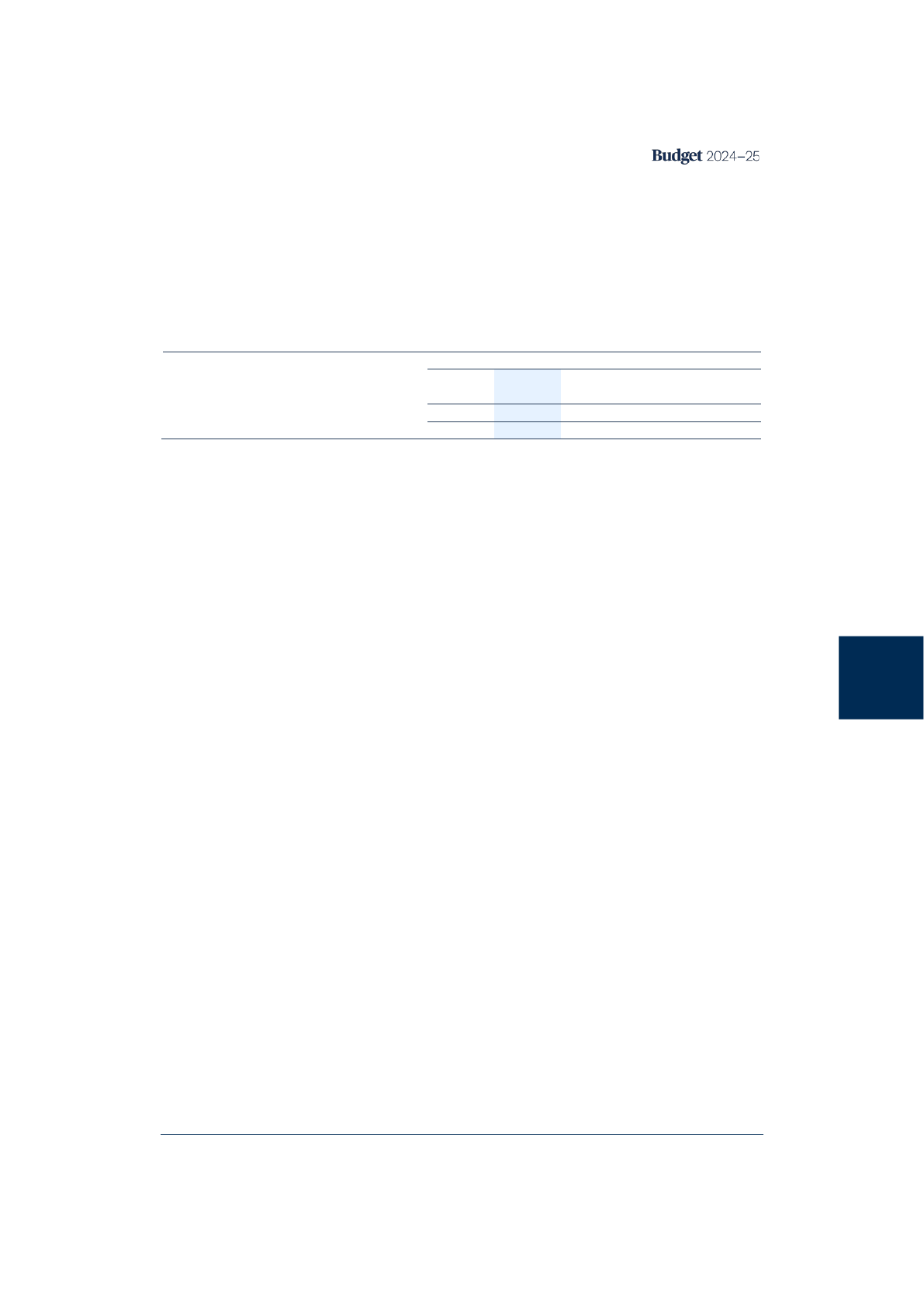

Table 1.1: Major economic parameters

(a)

Outcome

Forecasts

2022-23

2023-24

2024-25

2025-26

2026-27

2027-28

Real GDP

3.1

1 3/4

2

2 1/4

2 1/2

2 3/4

Employment

3.5

2 1/4

3/4

1 1/4

1 3/4

1 3/4

Unemployment rate

3.6

4

4 1/2

4 1/2

4 1/2

4 1/4

Consumer price index

6.0

3 1/2

2 3/4

2 3/4

2 1/2

2 1/2

Wage price index

3.7

4

3 1/4

3 1/4

3 1/2

3 1/2

Nominal GDP

9.9

4 3/4

2 3/4

4

5 1/4

5 1/4

a) Real GDP and Nominal GDP are percentage change on preceding year. Employment, the consumer

price index and the wage price index are through-the-year growth to the June quarter.

The unemployment rate is the rate for the June quarter.

Source: ABS Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product; Labour Force

Survey, Australia; Wage Price Index, Australia; Consumer Price Index, Australia; and Treasury.

Following a $22.1 billion surplus in 2022–23, another $9.3 billion surplus is now forecast for

2023–24 – the first back-to-back surpluses in almost two decades and a $65.9 billion

improvement from PEFO.

The Government is supporting monetary policy to keep the pressure off inflation by

targeting a surplus and banking 96 per cent of tax receipt upgrades in 2023–24. Since

coming to government, 82 per cent of tax upgrades have been returned to the budget.

A deficit of $28.3 billion (1.0 per cent of GDP) is forecast in 2024–25. The larger deficit is

driven by the Government’s cost-of-living relief and addressing unavoidable spending

including terminating health funding and frontline services. Over the six years to 2027–28,

the underlying cash balance is stronger in every year compared to PEFO and has improved

by a cumulative $214.7 billion.

The upgrades to receipts in this Budget are much smaller than recent budget updates, at

around a fifth of the average of the previous three Budgets. This Budget sees tax receipts,

excluding GST and policy decisions, increasing since MYEFO by $8.2 billion in 2024–25 and

$27.0 billion over the forward estimates.

Real payments growth has been limited to an average 1.4 per cent per year over the period

since coming to government to 2027–28, compared to around 3.2 per cent over the past

30 years. The Government has identified $32.2 billion in budget improvements in this

Budget, bringing the total to $104.8 billion since coming to government.

Budget Paper No. 1 |

Statement 1: Budget Overview | Page 7

Gross debt as a share of the economy is projected to be lower than at MYEFO and PEFO in

every year of the forward estimates and medium term, helping to rebuild fiscal buffers to

prepare for future challenges. Gross debt is projected to be $183.0 billion lower in 2024–25

than at PEFO. The improvements to the Budget position since PEFO will save around

$80 billion in interest costs over the decade.

Table 1.2: Budget aggregates

Actual

Estimates

Projections

2022-23

2023-24

2024-25

2025-26

2026-27

2027-28

Total(a)

2034-35

$b

$b

$b

$b

$b

$b

$b

Underlying cash balance

22.1

9.3

-28.3

-42.8

-26.7

-24.3

-112.8

Per cent of GDP

0.9

0.3

-1.0

-1.5

-0.9

-0.8

-0.1

Gross debt(b)

889.8

904.0

934.0

1,007.0

1,064.0

1,112.0

Per cent of GDP

34.7

33.7

33.9

35.1

35.2

34.9

30.2

Net debt(c)

491.0

499.9

552.5

615.5

660.0

697.5

Per cent of GDP

19.2

18.6

20.0

21.5

21.8

21.9

18.7

a) Total is equal to the sum of amounts from 2023–24 to 2027–28.

b) Gross debt measures the face value of Government Securities (AGS) on issue.

c) Net debt is the sum of interest-bearing liabilities (which includes AGS on issue measured at market

value) less the sum of selected financial assets (cash and deposits, advances paid and investments,

loans and placements).

Responsible economic management

The Government’s Economic and Fiscal Strategy is making the economy and the budget

stronger, more resilient and more sustainable over the medium term. The back-to-back

surpluses reflect the Government’s discipline to return 96 per cent of tax upgrades to

Budget in 2023–24 and 82 per cent of tax upgrades since PEFO. Since coming to

government real payments growth has been limited to an average 1.4 per cent per year and

$104.8 billion in budget improvements have been identified up to 2027–28.

The Government is directly reducing inflation through responsible cost-of-living measures.

In 2024–25, these measures are estimated to directly reduce inflation by ½ of a percentage

point and are not expected to add to broader inflationary pressures.

In this Budget, the Government has identified $27.9 billion in savings and spending

reprioritisations to support the Government’s commitment to improve the quality of

spending and ensure spending is targeted at national priorities. This brings the total

savings and spending reprioritisations since PEFO to $77.4 billion.

The Budget also incorporates the impact of National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS)

reforms being undertaken by the Government as part of the Getting the NDIS back on track

measure. These reforms are expected to offset increases in NDIS payments of $14.4 billion

over four years from 2024–25, based on the NDIS Actuary’s revised projections without

further action.

This Budget also includes measures to strengthen the fairness and sustainability of the tax

system, which will improve the budget by $3.1 billion over five years. This includes

| Budget Paper No. 1

Page 8 | Statement 1: Budget Overview

funding for the Australian Taxation Office to address fraud, extending tax compliance

activities focused on domestic and multinational tax avoidance, the shadow economy and

the personal income tax system, and strengthening the foreign resident capital gains tax

regime to ensure foreign residents pay their fair share of tax in Australia.

The Government has taken $15.4 billion in unavoidable spending decisions, including to

extend terminating programs and continue to address legacy issues left by the former

Government. Investment in these critical areas ensures that we keep existing programs in

place to prevent any cuts to the services that Australians rely on. This includes funding to:

• address pressures at Services Australia, help stabilise claim processing performance and

continue emergency response capability, continue to operate, maintain and enhance

myGov, and improve safety for staff and customers

• address unavoidable cost pressures for existing projects in the Infrastructure Investment

Program

• extend terminating health programs and to continue the COVID-19 response

• support digital capability and sustainment of aged care systems

• address underfunding at Home Affairs and the Australian Border Force, helping to

sustain operations and maintain capability to secure our borders.

Budget priorities

Easing cost-of-living pressures

Australian households and businesses are still under pressure from high, but moderating,

inflation and higher interest rates. In addition to the Government’s cost-of-living tax cuts,

this Budget delivers a further $7.8 billion in cost-of-living relief. The Government’s income

tax changes, energy bill relief, and rent assistance that will take pressure off households

and are not expected to add to broader inflationary pressures. The Government is also

delivering initiatives to build a more competitive and dynamic economy to put downward

pressure on prices into the future.

Tax cuts for every Australian taxpayer

The Government has legislated tax cuts for all 13.6 million Australian taxpayers from

1 July 2024 to provide cost-of-living relief, return bracket creep and boost labour supply.

The Government’s tax changes have been designed to ensure they will not add to the

inflation outlook.

Budget Paper No. 1 |

Statement 1: Budget Overview | Page 9

From 1 July 2024:

• the 19 per cent tax rate will be reduced to 16 per cent

• the 32.5 per cent tax rate will be reduced to 30 per cent

• the income threshold above which the 37 per cent tax rate applies will be increased from

$120,000 to $135,000

• the income threshold above which the 45 per cent tax rate applies will be increased from

$180,000 to $190,000.

The Government’s tax cuts return bracket creep and lower average tax rates for all

taxpayers, with an average tax cut of $1,888. Someone earning an average income will pay

$21,915 less in tax by 2034–35 as a result of the tax cuts. The reductions in average tax rates

provide all taxpayers, particularly low- to middle-income taxpayers, with greater

protection against bracket creep.

Compared to previously legislated settings, 11.5 million taxpayers (or 84 per cent of

taxpayers) will receive a bigger tax cut. This includes 2.9 million lower-income taxpayers

with taxable income of $45,000 or less, who would not have received any support

previously.

The tax cuts are expected to increase labour supply by around 930,000 hours per week,

equivalent to around 25,000 full time jobs. This increase is primarily driven by increases in

hours worked and participation of women and individuals in the low- to middle-income

range, particularly those earning between $25,000 and $75,000. All 6.5 million women

taxpayers will receive a tax cut in 2024–25, and 90 per cent of women taxpayers will get a

bigger tax cut, increasing the financial return from work and supporting participation.

The Government has increased the Medicare levy low-income thresholds for singles,

families and seniors from 1 July 2023 to provide additional cost-of-living relief. This will

mean more than one million Australians on lower incomes continue to be exempt from

paying the Medicare levy or pay a reduced levy rate.

New power bill relief

The Government is directly easing cost-of-living pressures for households and eligible

small businesses through additional energy bill relief, which will be extended to all

households, at a cost of $3.5 billion. From 1 July 2024, the Government will deliver rebates

of $300 to every household and $325 to around one million small businesses across the

country. Extending energy bill relief and expanding it to all households is expected to

directly reduce headline inflation by around ½ a percentage point in 2024–25 and is not

expected to add to broader inflationary pressures.

| Budget Paper No. 1

Page 10 | Statement 1: Budget Overview

Support for renters

The Government recognises that many renters are still facing pressure from rising rents.

This Budget provides further relief for renters by increasing maximum rates of

Commonwealth Rent Assistance by an additional 10 per cent, at a cost of $1.9 billion over

five years from 2023–24. This increase will support nearly one million households and help

further relieve rental stress among low-income households.

This builds upon relief provided in the 2023–24 Budget, where the Government delivered

the largest increase in Commonwealth Rent Assistance in more than 30 years, increasing

maximum rates by 15 per cent. This is the first back-to-back real increase in the maximum

rates of Commonwealth Rent Assistance in more than three decades.

Cheaper medicines

The Government is continuing to assist households facing cost-of-living pressures by

keeping down the costs of medicines. Instead of rising with inflation, medicines will be

kept cheaper through a one-year freeze on the maximum Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme

(PBS) patient co-payment for everyone with a Medicare card and a five-year freeze for

pensioners and other concession cardholders. The Government is working to finalise the

new Eighth Community Pharmacy Agreement, supported by up to an additional $3 billion

in funding.

Supporting students

The Government will cut $3 billion in student debt for more than three million Australians.

This will provide relief for everyone with Higher Education Loan Program (HELP) and

other student loan debt, while continuing to protect the integrity and value of the student

loan system which has massively expanded access to tertiary education. In response to the

Universities Accord, the Government will cap the HELP indexation rate to be the lower of

either the Consumer Price Index (CPI) or the Wage Price Index (WPI). The Government will

backdate this relief to all HELP, VET Student Loan, Australian Apprenticeship Support

Loan and other student support loan accounts that existed on 1 June 2023. This will benefit

all Australians with a HELP debt, fix last year’s spike and prevent growth in debt from

outpacing wages in the future.

These changes complement other investments to set students up for success including

payments for mandatory placements and to apprentices in priority occupations.

Support for vulnerable Australians

The Government is extending eligibility for the existing higher base rate of JobSeeker

Payment to single JobSeeker Payment recipients with an assessed partial capacity to work

between zero and 14 hours per week. Combined with a higher rate of Energy Supplement

this will provide an increase of at least $54.90 per fortnight for these recipients. This is in

addition to the broader $40 fortnightly base rate increase for working age and student

payments announced in the 2023–24 Budget and regular indexation increases.

Budget Paper No. 1 |

Statement 1: Budget Overview | Page 11

The Government is also supporting social security recipients to manage their budgets by

continuing the freeze on social security deeming rates for financial investments at their

current levels for a further 12 months until 30 June 2025. This will benefit around

876,000 income support recipients, including around 450,000 Age Pensioners.

The Government is providing $138.0 million over five years for community services

delivered under the Financial Wellbeing and Capability Activity program, including

financial resilience, capability building and crisis support. This program supports over

580,000 people experiencing financial distress including to help meet the cost of unexpected

bills and expenses.

A fair go for consumers

The cost of food and groceries is putting many family budgets under significant pressure.

The Government is committed to ensuring that the right regulatory settings are in place to

support a competitive and sustainable food and grocery industry in Australia.

The Government has appointed Dr Craig Emerson to review the Food and Grocery Code of

Conduct, to promote good faith commercial dealings between supermarkets and suppliers.

The Government has also directed the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission

(ACCC) to undertake a price inquiry into the supermarket sector, to ensure Australians are

paying a fair price for their groceries.

Further, the Government has commissioned respected consumer advocate CHOICE to

prepare quarterly reports, looking at the comparative cost of a basket of goods from

retailers. This initiative will help consumers to make an informed choice and save money.

The Government has announced the biggest reform to Australia’s merger control system in

almost 50 years, and is working with state and territory governments over the coming year

to revitalise National Competition Policy. These initiatives will promote a more competitive

and productive economy, support living standards and put downward pressure on prices

into the future.

Building more homes for Australians

This Budget invests in delivering the housing and infrastructure needed to support

Australia’s thriving cities and regional communities. The Government is boosting housing

supply including social and affordable housing and investing in infrastructure to build

more homes in well-located areas. The Government is also investing in the road, rail and

port infrastructure needed to make our cities and regional communities more liveable and

connect them with each other and to the world.

Help to build, rent and buy

The Government will make a further $1 billion available to the states and territories to

boost housing supply in well-located areas. This includes funding to unblock local

infrastructure bottlenecks that are preventing housing from being built by supporting

| Budget Paper No. 1

Page 12 | Statement 1: Budget Overview

better shared facilities and essential services such as water, power, and roads. This

responds directly to requests from states and territories for an earlier boost to infrastructure

funding to help them meet National Cabinet’s 1.2 million homes target and achieve their

share of the $3 billion New Homes Bonus incentive payment being offered by the

Commonwealth.

Under the new National Agreement on Social Housing and Homelessness the Government

is offering the states and territories an additional $423.1 million over five years for social

housing and homelessness services, bringing the total to $9.3 billion. For this new

agreement, the Commonwealth will double its dedicated funding allocation for

homelessness services – funding the states and territories must match.

The Government will implement regulatory requirements to ensure public universities

provide more purpose-built student accommodation. The Government will consult on the

details of these requirements and transition arrangements prior to commencement. This

will help increase the supply of student accommodation for all students and will ease

pressure on the private rental market.

To encourage investment in the Build to Rent sector, the Government will allow foreign

investors to purchase established Build to Rent developments and apply lower application

fees to these investments. This builds on the Government’s 2023–24 MYEFO commitment to

apply lower fees to foreign investment applications for new Build to Rent developments.

Building the construction workforce

To strengthen the pipeline of skilled workers in the construction and housing sector, the

Government is investing $88.8 million to deliver 20,000 additional Fee-Free TAFE and VET

places in courses relevant to construction, including increased access to pre-apprenticeship

programs. This is on top of more than 355,000 Fee-Free TAFE places delivered in 2023, and

the 300,000 places being delivered from 2024 to 2026 in areas of skills need.

The Government will also provide $1.8 million to deliver streamlined skills assessments for

around 1,900 migrants from comparable countries who wish to work in Australia’s housing

construction industry.

More Social and Affordable Housing

The first $500 million minimum annual disbursement from the $10 billion Housing

Australia Future Fund (HAFF) will be made in 2024–25. These funds will support social,

affordable, and acute housing, including for women and children impacted by family

violence and older women at risk of homelessness. The Government will also provide

additional concessional financing of up to $1.9 billion to community housing providers and

other charities to support delivery of new social and affordable dwellings under the HAFF

and the National Housing Accord.

The Government will further expand the Affordable Housing Bond Aggregator program

by increasing Housing Australia’s liability cap by $2.5 billion to $10 billion, and lend an

additional $3 billion to Housing Australia to support ongoing delivery of the program.

Budget Paper No. 1 |

Statement 1: Budget Overview | Page 13

These changes will enable Housing Australia to provide more low-cost finance to

community housing providers.

The Government will target $1 billion for social housing under the National Housing

Infrastructure Facility towards crisis and transitional accommodation for women and

children fleeing domestic violence, and youth.

Better transport for cities, regions and suburbs

The Government is focusing its over $120 billion ten-year infrastructure investment

pipeline on nationally significant projects which improve the prosperity, accessibility and

liveability of our cities, regions and communities. This Budget provides $16.5 billion over

10 years from 2024–25 for priority road and rail infrastructure projects, including additional

funding of $3.3 billion for the North East Link and $437.3 million for suburban road

upgrades in south eastern and northern Melbourne.

To ensure Perth has an effective public transport network to support its growth, this

Budget provides an additional $1.4 billion to existing METRONET projects and

$300 million for a new High-Capacity Signalling Program.

This Budget will provide every state and territory with additional funding for new and

existing infrastructure projects over the forward estimates; with $9.5 billion additional

being provided over the forward estimates.

Better transport for Western Sydney

The Government is committed to unlocking the economic potential of Western Sydney,

investing $2 billion of additional infrastructure funding this Budget. This brings total

infrastructure investment in Western Sydney to $17.3 billion.

Investments in more efficient transport networks will transform the way communities live

and move within Western Sydney and connect people to opportunities in the region. Key

projects include:

• $1.9 billion for priority road and rail projects; including Mamre Road, Elizabeth Drive,

and Richmond Road from the M7 Motorway to Townson Road

• $100.0 million for zero emission rapid bus infrastructure to connect the metropolitan

centres of Penrith, Liverpool and Campbelltown to the Western Sydney International

(Nancy-Bird Walton) Airport and Aerotropolis at Bradfield.

Western Sydney International Airport is due to welcome its first travellers and freight in

2026. The Government is providing a further $302.6 million over five years to enable

operations at the Airport, including for border agencies to progress design, fit out and

commissioning of facilities, provide federal policing and establish a detector dog unit.

| Budget Paper No. 1

Page 14 | Statement 1: Budget Overview

Meeting the infrastructure needs for South East Queensland

The Government is investing $2.2 billion in vital transport infrastructure projects in South

East Queensland to accommodate a population that has grown by over 50 per cent in the

last 20 years, better integrating the region, and unlocking future housing development.

Investments in this Budget will enhance rail connectivity and reduce trip times between

Brisbane and the Sunshine Coast, including an additional $1.2 billion for the Direct

Sunshine Coast Rail and $226.7 million for the Beerburrum to Nambour Rail Upgrade,

ahead of the 2032 Olympic and Paralympic Games. In addition, $431.7 million is provided

for the Coomera Connector Stage 1 project, and an extra $467.2 million is being committed

for the Bruce Highway Corridor, including in South East Queensland.

Better connections for regional and remote communities

Australia’s regions rely on efficient and resilient transport links to connect communities

and businesses. The Government is investing $2.6 billion in road and rail projects in

regional Australia, including $541.7 million for upgrades to critical roads in Northern

Australia and an additional $290.1 million for the Gippsland Rail Line Upgrade. Following

the completion of additional planning, $720.0 million will be released for the construction

of the Inland Freight Route in Queensland, providing an alternative to the Bruce Highway

and improved connectivity between the NSW border and Charters Towers. The

Government is also investing $540.0 million to improve the reliability of the Australian Rail

Track Corporation’s interstate freight rail network, including $150.0 million to upgrade the

Maroona to Portland Line.

This Budget also provides $101.9 million to improve safety and accessibility at regional

airports, including funding to upgrade remote airstrips recognising their importance in

delivering healthcare and other services to remote communities.

Investing in a Future Made in Australia

This Budget invests $22.7 billion over the next decade to build a Future Made in Australia.

This plan is about maximising the economic and industrial benefits of the net zero

transformation and securing Australia’s place in a changing global economic and strategic

landscape.

The Future Made in Australia package encourages and facilitates the private sector

investment required for Australia to make the most of these structural shifts. It will help

Australia better attract and enable investment, encourage the transition to cheaper and

cleaner energy and support Australia to become a renewable energy superpower. It will

also value-add to our resources, strengthen our economic security, boost our innovation

and digital capabilities and invest in the highly skilled workforce of the future.

The Future Made in Australia plan recognises the best opportunities for Australia and its

people are at the intersection of industry, energy, resources, human capital, and our ability

to attract and deploy investment. It will help build a stronger, more diversified and more

Budget Paper No. 1 |

Statement 1: Budget Overview | Page 15

resilient economy powered by clean energy, in a way that creates secure, well-paid jobs in

our regions and suburbs, and benefits communities across Australia.

The Future Made in Australia plan is complemented by broader government priorities and

initiatives in this Budget. These include but are not limited to investments in education,

defence capabilities, trade and regional engagement and support for small business,

farmers and regions.

Attracting investment in key industries

The Government will legislate a Future Made in Australia Act and establish a National

Interest Framework to identify priority industries and guide investments associated with

these industries, to ensure they are responsible and targeted.

The Framework will have a focus on industries that contribute to net zero transformation

where Australia has a comparative advantage, and in areas where Australia has national

interest imperatives related to economic security and resilience. It will also allow for the

setting of new Community Benefit Principles to ensure government investment has flow on

benefits for the broader Australian community, and will complement the Buy Australian

Plan and Secure Jobs Plan.

New front door for investors

To facilitate the investment Australia’s dynamic economy needs, the Government will

establish a new front door for investors with major, transformational investment proposals

to make it simpler to invest in Australia and attract more global and domestic capital. The

single point of contact for investors and companies with major investment proposals will

streamline engagement with government, helping those investors and companies navigate

approvals processes and fast-tracking major projects where possible.

It is proposed the new front door will deliver a joined-up approach to investment attraction

and facilitation, identify priority projects related to the Government’s Future Made in

Australia agenda, support accelerated and coordinated approvals, and connect investors

with the Government’s Specialist Investment Vehicles. Its core functions and institutional

arrangements will be subject to consultation, led by the Treasury.

The Net Zero Economy Authority (NZEA) will continue to support regions affected by

energy system change through public and private investment, facilitating worker

transition, and driving skills development. The front door will work in partnership with

the NZEA to provide investment facilitation support and lead place-based co-investment.

The mandate of Export Finance Australia’s National Interest Account will be expanded to

provide financial support for projects where public investment can strengthen the

alignment of economic incentives with Australia’s national interests and incentivise private

investment at scale in the development of priority industries. Support from the National

Interest Account will be guided by the National Interest Framework and Community

Benefit Principles, outlined in Box 1.1. Export Finance Australia will continue to rigorously

assess the technical and commercial viability of proposed projects.

| Budget Paper No. 1

Page 16 | Statement 1: Budget Overview

Strengthening and streamlining approvals

The Government is making it easier to invest in transformational projects by streamlining

approval processes in ways that strengthen standards. Through smarter use of data, better

decision-making processes and appropriate resourcing, this Budget provides a faster

pathway to better decisions on environmental, energy, planning, cultural heritage and

foreign investment approvals.

The Government is providing $96.6 million over four years to support timely

environmental approval decisions by providing more support for project assessments,

better planning in priority regions and more funding for threatened species research.

This Budget provides an additional $19.9 million over four years to support assessment of

priority renewable energy projects, to support the identification of national priority

projects, working in collaboration with states and territories. Together, these measures

support the recently announced second stage of the Government’s Nature Positive Plan.

The Government is also providing $17.7 million over three years to help reduce the backlog

and support the administration of complex cultural heritage applications in the system.

The Government is working in partnership with states and territories to improve approval

processes for energy infrastructure. This Budget invests $20.7 million over seven years in

improving community engagement in energy infrastructure, including through

introducing voluntary national standards for renewable energy developers, improving

community benefits realisation in regional communities, and permanently establishing the

Australian Energy Infrastructure Commissioner. Through the National Energy

Transformation Partnership and support for the Australian Energy Market Operator grid

connections pilot, the Government is also improving how planning decisions and electricity

grid connections are delivered. To date, these actions have fast-tracked the delivery of an

additional 3.2 gigawatts of generation capacity.

Foreign Investment Framework

This Budget provides $15.7 million to deliver a stronger, more streamlined and more

transparent approach to foreign investment. These reforms will help attract the foreign

capital flows Australia needs while protecting the national interest in an increasingly

complex economic and geostrategic environment.

The Government will apply greater scrutiny to high-risk investments and enhance

monitoring and enforcement activities. At the same time, low-risk investments will be

processed faster to help bring in the capital Australia needs. This will be supported by

Treasury adopting a new target of processing 50 per cent of foreign investment applications

within the 30-day statutory timeframe from 1 January 2025.

Sustainable finance strategy

The Government is investing $17.3 million to deliver its ambitious sustainable finance

agenda to mobilise private sector investment in the net zero transformation. This Budget

fully funds completion of Australia’s preliminary sustainable finance taxonomy, as well as

development of a labelling regime for investment products marketed as sustainable.

Budget Paper No. 1 |

Statement 1: Budget Overview | Page 17

An additional $1.3 million will enable the development of guidance on best practices for

businesses disclosing net zero transition plans.

The Government is also issuing around $7 billion of green bonds in 2023–24 which

will support the development of Australia’s broader sustainable finance markets.

The sustainable finance strategy will support reforms such as the new front door for

investors and those that enhance Australia’s ability to attract investment needed to make

Australia a renewable energy superpower.

Making Australia a renewable energy superpower

The Government is making substantial investments to establish Australia as a renewable

energy superpower. Maximising the opportunities of cheaper, cleaner, more reliable energy

and the transformation to net zero are foundational in building a future made in Australia.

Powering Australia with cheaper, cleaner, more reliable energy

The Government is unlocking over $65 billion of investment in renewable generation and

clean dispatchable capacity through the Capacity Investment Scheme. This will transform

Australia’s electricity grid and provide the foundation for an economy powered by

renewables.

This Budget commits $27.7 million to help Australians benefit from cheaper, cleaner energy

sooner by supporting development of priority reforms to ensure consumer energy

resources, such as rooftop solar, household batteries and electric vehicles, contribute to our

grid. It also introduces the New Vehicle Efficiency Standard, which will save Australians

around $95 billion at the bowser by 2050 while reducing transport emissions.

Unlocking investment in net zero industries and jobs

This Budget accelerates the growth of new industries by providing a $1.5 billion extension

over seven years to the Australian Renewable Energy Agency’s industry-building

investments and establishing the $1.7 billion Future Made in Australia Innovation Fund.

This Fund will support innovation, commercialisation, pilot and demonstration projects

and early stage development in priority sectors, including renewable hydrogen, green

metals, low carbon liquid fuels and clean energy technology manufacturing such as

batteries. The Budget also invests $44.4 million in an Energy Industry Jobs Plan and

$134.2 million for skills and employment support in key regions impacted by the net zero

transition.

The Government is establishing a Hydrogen Production Tax Incentive for renewable

hydrogen produced from 2027–28 to 2039–40 to incentivise greater investment in renewable

hydrogen production, at an estimated cost of $6.7 billion over the decade. This Government

is also expanding the Hydrogen Headstart program by $1.3 billion, supporting early

movers to invest in the industry’s development.

| Budget Paper No. 1

Page 18 | Statement 1: Budget Overview

These investments are supported by an extension to the First Nations Renewable Hydrogen

Engagement Fund and the 2024 National Hydrogen Strategy, which outlines Australia’s

approach to becoming a global hydrogen leader through the development of a domestic

low emissions hydrogen industry, working with international partners. Together, these

new commitments are expected to unlock $50 billion in private capital investment into the

Australian renewable hydrogen industry by 2030.

Green metals and low carbon liquid fuels are also key to Australia’s net zero

transformation. This Budget initiates further consultation on policy approaches to

accelerate investment and incentivise efficient production of green metals and low carbon

liquid fuels.

Boosting demand for Australia’s green exports

The Government is supporting the growth of green industries and making it easier for

businesses and trading partners to source low-emissions products by developing product

standards for green products. The Budget provides $32.2 million to fast-track the initial

phase of the Guarantee of Origin scheme focused on renewable hydrogen in 2024–25,

before expanding the scheme to accredit the emissions content of green metals and low

carbon liquid fuels.

Realising the opportunities of net zero transformation

Australia is committed to reaching net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 and is

developing six sector plans covering electricity and energy, transport, industry, resources,

agriculture and land, and the built environment. This Budget continues the Government’s

investment in effective emissions abatement, including through $63.8 million to support

emissions reduction efforts in the agriculture and land sector.

The Government is also investing $399.1 million to establish the Net Zero Economy

Authority, which will support the economy-wide net zero transformation that is underway

by acting as a catalyst for private and public investment, major project development,

employment transition, skills and community development. The Budget strengthens

community engagement in and benefits from the transition by investing $48.0 million in the

reforms to the Australian Carbon Credit Unit scheme and $20.7 million to improve

community engagement and realise community benefits for regional communities affected

by the energy transition.

Adding value to resources and strengthening economic security

Critical minerals are a key input to many clean energy technologies. Scaling the supply of

critical minerals will be essential in order to support the global transition to net zero by

2050. Australia can improve the resilience of supply chains and add more value to our

resources by processing and refining critical minerals.

Budget Paper No. 1 |

Statement 1: Budget Overview | Page 19

Backing a strong resources sector

Critical minerals are a key input to many clean energy technologies. Scaling the supply of

critical minerals will be essential to support the global transition to net zero by 2050.

By adding more value to our resources by processing and refining critical minerals,

Australia can improve the resilience of global supply chains.

This Budget establishes a Critical Minerals Production Tax Incentive for eligible processing

and refining costs from 2027–28 to 2039–40 to incentivise investment in refining and

processing of the 31 critical minerals currently identified on the Government’s Critical

Minerals List, at an estimated cost of $7.0 billion over the decade.

The Government is also partnering with states and territories to complete pre-feasibility

studies for critical minerals common-use infrastructure through the Critical Minerals

National Productivity Initiative, and supporting up to $1.2 billion in priority critical

minerals projects through the Critical Minerals Facility and Northern Australia

Infrastructure Facility. This includes the Alpha HPA alumina project in Queensland and

Arafura Rare Earth’s Nolans Rare Earth project in the Northern Territory.

The Government is investing $556.1 million over ten years to progressively map Australia’s

potential for critical minerals, alternative energy, groundwater and other resources,

providing scientific information to guide future investment.

Manufacturing clean energy technologies

The Government is providing $1.5 billion in support administered by the Australian

Renewable Energy Agency for the manufacturing of clean energy technologies that

strengthens supply chain resilience. The $1 billion Solar Sunshot program will incentivise

private investment in solar panel manufacturing capability and the Battery Breakthrough

Initiative, costing $523.2 million over seven years, will promote further opportunities to

add value to Australia’s critical minerals and target the high-value opportunities in the

battery manufacturing value chain.

Building resilient supply chains

Resilient supply chains will be critical to delivering the Government’s renewable energy

superpower vision. The Government is working with the states and territories through the

National Energy Transformation Partnership to secure the inputs required to achieve the

82 per cent renewable energy target. This is on top of the $2.2 million over two years

previously committed to improve supply chain transparency and identify future demand

for critical inputs.

The Government will also invest an additional $14.3 million to improve the

competitiveness of the Australian economy by working with trade partners to support

global rules on unfair trade practices and to negotiate benchmarks for trade in high-quality

critical minerals.

| Budget Paper No. 1

Page 20 | Statement 1: Budget Overview

Box 1.1: The Future Made in Australia National Interest Framework

The net zero transition and heightened geostrategic competition are transforming

the global economy. Australia’s comparative advantages, capabilities and trade

partnerships mean that these global shifts present a profound opportunity for

Australian workers and businesses. In certain circumstances, targeted public

investment can strengthen the alignment of economic incentives with Australia’s

national interests and incentivise private investment at scale to develop priority

industries.

In considering the prudent basis for public investment, the Government has had

regard to: Australia’s grounds for lasting competitiveness, the role the industry will

play in securing an orderly path to net zero and in building Australia’s economic

resilience and security, whether the industry will build key capabilities, and whether

the barriers to private investment can be resolved through public investment in a

way that delivers compelling public value.

These five tests have informed the development of a National Interest Framework

(the Framework), which will impose rigour on Government’s decision making on

significant public investments, particularly those used to incentivise private

investment at scale. The Framework has two streams that will be used to identify

priority industries and principles for government support.

• Net zero transformation stream: Industries may warrant public investment

under this stream if Australia is assessed to have grounds for sustained

comparative advantage in a net zero global economy, and public investment is

needed for the sector to make a significant contribution to emissions reduction at

an efficient cost.

• Economic resilience and security stream: Industries may warrant public

investment under this stream if some level of domestic capability is necessary or

efficient to deliver adequate economic resilience and security, and the private

sector would not invest in this capability in the absence of public investment.

The Government will apply community benefit principles in relation to investments

in priority industries. These principles will have a focus on investment in local

communities, supply chains and skills, and the promotion of diverse workforces and

secure jobs.

continued on next page

Budget Paper No. 1 |

Statement 1: Budget Overview | Page 21

Box 1.1: The Future Made in Australia National Interest Framework

(continued)

The following industries are consistent with the National Interest Framework

in the context of the Government’s Future Made in Australia agenda in the

2024–25 Budget:

Net zero transformation

Economic resilience and security

Renewable hydrogen

Green metals

Low carbon liquid fuels

Processing and refining of critical minerals

Manufacturing of clean energy technologies

Treasury will be responsible for the Framework. Further details will be made

available and consulted on as part of the Future Made in Australia legislative

package. The Framework is not intended to direct all Government investments or

replace other policy frameworks.

The Future Made in Australia package in the 2024–25 Budget puts in place

meaningful but targeted incentives for private investment consistent with the

Framework, including production tax credits for renewable hydrogen and critical

minerals processing and refining. The Future Made in Australia package also

includes broader investments in the Government’s growth agenda, including critical

technologies, defence priorities, skills in priority sectors, a competitive business

environment and reforms to better attract and deploy investment.

Investing in digital, science and innovation

Science and research lay the foundations for new industries and productivity growth.

This Budget invests in the data, technology and capabilities that will underpin future

innovations.

Investing in new technologies and capabilities

Building on Australia’s existing strengths in research and applied technology, the

Government is partnering with PsiQuantum and the Queensland Government to develop

Australia’s quantum computing capabilities. As part of this $466.4 million partnership,

PsiQuantum will build the world’s first commercial-scale quantum computer in Brisbane,

become the anchor tenant in a growing quantum precinct in Brisbane and deliver PhD

positions and research collaborations.

The Government is initiating an independent, strategic examination of Australia’s research

and development system to ensure a robust and sustainable policy for a future made in

Australia and to maximise the impact of investments in science, research and innovation.

| Budget Paper No. 1

Page 22 | Statement 1: Budget Overview

The Government is providing $448.7 million to partner with the United States in the

Landsat Next satellite program to provide access to critical data to monitor the earth’s

climate, agricultural production, and natural disasters, and $145.4 million for the National

Measurement Institute to support its core scientific capabilities. To increase diversity in

education and industry, the Government will invest $38.2 million to provide funding for

a range of STEM programs.

Modernising and digitising industries

To guide safe and responsible development of new technologies, the Government will

invest $39.9 million to progress Australia’s regulatory response to ensure safe and

responsible development and deployment of AI and release a National Robotics Strategy to

promote the responsible production and adoption of robotics and automation technologies

in Australia.

The Government will invest $288.1 million to support the further delivery and expansion of

Australia’s Digital ID System so more Australians can realise the economic, security and

privacy benefits of Digital ID.

Reforming tertiary education and investing in priority skills

A highly skilled workforce will be a core enabler of the Government’s ambitious agenda to

modernise the Australian economy, drive productivity growth and build a future made in

Australia. This Budget invests to build and enhance Australia’s human capital base through

key reforms to the tertiary education sector.

As part of the response to the Universities Accord, the Government will set a tertiary

attainment target of 80 per cent of the working age population to have a VET or higher

education qualification by 2050. To achieve this target, the Government is committing

$1.1 billion over five years, and an additional $2.7 billion from 2028–29 to 2034–35, to

expand access to higher education and support future productivity.

Broadening access to university

Increasing tertiary attainment and meeting the 80 per cent target will require greater

numbers of underrepresented students to attend university. To help more of these students

succeed, the Government is committing to needs-based funding. Universities will receive

additional funding to provide dedicated support to students from low-socioeconomic

backgrounds, First Nations students, students with disability and students studying at

regional campuses.

The Government will also redesign the university funding model to drive attainment levels

that meet our long-term skills needs. To provide more pathways to university for students

who do not qualify for direct entry, the Government is also investing $350.3 million to

expand access to free university enabling courses from 1 January 2025.

Budget Paper No. 1 |

Statement 1: Budget Overview | Page 23

Supporting students on placements

The Government is investing $427.4 million over four years to make Commonwealth Prac

Payments to students studying in critical sectors while they undertake mandatory

placements. Support will be available to nursing including midwifery, teaching and social

work students in higher education and nursing students in VET. Eligible students will

receive payments of $319.50 per week for the duration of their placement. This is expected

to support more than 73,000 students per year, will help to alleviate the financial impact of

being on placement and will support retention in courses related to sectors with skills

shortages.

Investing in priority skills

The Government is supporting gender equality and women’s participation by driving

structural and cultural change in work and training environments in traditionally

male-dominated industries. The Government is investing $55.6 million to launch the

Building Women’s Careers program which will deliver around ten large-scale projects, and

several smaller local projects, to support women to access flexible training in clean energy,

construction, tech and advanced manufacturing.

To support apprentice retention and completion rates, the Government has committed to

increase Phase Two Incentive System payments for apprentices in priority occupations

from $3,000 to $5,000 and hiring incentives for priority occupation employers from

$4,000 to $5,000 for 12 months from 1 July 2024. This will provide certainty to apprentices

while the Government awaits the findings of the Strategic Review of the Australian

Apprenticeship Incentive System.

To strengthen the pipeline of skills in the construction sector, the Government is investing

$88.8 million to deliver 20,000 additional Fee-Free TAFE places in courses relevant to

construction, including increased access to pre-apprenticeship programs. This is on top of

more than 355,000 Fee-Free TAFE places delivered in 2023, and the 300,000 places being

delivered from 2024 to 2026 in areas of skills need.

The Government is investing $91.0 million to develop the clean energy workforce,

including by turbocharging the VET teacher, trainer and assessor workforce, and funding

clean energy training facility upgrades and capacity expansion. Expanded eligibility for the

New Energy Apprenticeships Program will also allow more apprentices to access $10,000

payments and will increase completions in priority sectors. Eligible Group Training

Organisations will be reimbursed for reducing fees to small-to-medium enterprises seeking

clean energy, manufacturing, and construction apprentices.

The Government is reforming Australia’s migration system to drive greater economic

prosperity and restore its integrity, implementing actions outlined in the Migration

Strategy. This Budget supports skills in demand, with around 70 per cent of the permanent

Migration Program allocated to skilled visa categories. The Government will also introduce

a new National Innovation visa to attract exceptionally talented migrants and replace the

Global Talent visa and the Business Innovation and Investment visa. These actions

complement reforms being developed for the points test used for certain skilled visas.

| Budget Paper No. 1

Page 24 | Statement 1: Budget Overview

The actions underway as part of the Migration Strategy are delivering a better managed

migration system. Government actions are estimated to reduce net overseas migration by

110,000 people over the forward estimates from 1 July 2024. Net overseas migration is

forecast to approximately halve from 528,000 in 2022–23 to 260,000 in 2024–25.

Strengthening our defence industry capability

The Government is committed to delivering an integrated, focused Australian Defence

Force to protect the nation in a complex geostrategic environment, including by

strengthening defence supply chains.

National Defence Strategy

As part of the 2024 National Defence Strategy, the Government is investing $330 billion

over the next decade to deliver a rebuilt Integrated Investment Program (IIP) to support the

required shift in Defence’s posture and structure, and deliver critical capabilities for the

Australian Defence Force (ADF). This includes an additional $50.3 billion over the decade

to uplift the ADF’s preparedness including through long-range strike capability and

accelerating the modernisation of the Royal Australian Navy’s surface combatant fleet.

The Government’s significant investment in a rebuilt IIP involves reprioritisation of

$22.5 billion over the next four years and $72.8 billion across the decade to support

accelerated delivery of critical capabilities for the ADF.

Developing defence industry and skills

The Government will provide $101.8 million over seven years from 2024–25 to attract and

retain the Australian industrial workforce required to support the delivery of Australia’s

conventionally-armed nuclear-powered submarines. This includes initiatives delivered

through the Skills and Training Academy, such as a pilot apprenticeship program in trades

required to support the nuclear-powered submarine enterprise. It will also support

scholarships for students studying relevant undergraduate STEM courses.

The Government’s Defence Industry Development Strategy will further support the

creation of a resilient and competitive sovereign industrial base, providing economic