CITY OF MELBOURNE HOUSING NEEDS ANALYSIS

FINAL REPORT

Prepared for

JULY 2019

City of Melbourne

Independent insight.

20190171 Final Report 050716

© SGS Economics and Planning Pty Ltd 2019

This report has been prepared for City of Melbourne. SGS Economics and Planning

has taken all due care in the preparation of this report. However, SGS and its

associated consultants are not liable to any person or entity for any damage or loss

that has occurred, or may occur, in relation to that person or entity taking or not

taking action in respect of any representation, statement, opinion or advice

referred to herein.

SGS Economics and Planning Pty Ltd

ACN 007 437 729

www.sgsep.com.au

Offices in Canberra, Hobart, Melbourne, Sydney

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABBREVIATIONS AND KEY TERMS 1

SUMMARY 2

1. INTRODUCTION 9

Background 9

Purpose of this study 10

Principles guiding SGS’s approach to the study 10

Structure of the report 11

2. MEASURING AFFORDABLE HOUSING NEED IN MELBOURNE 12

2.1 Scope and definitions 12

2.2 Method 15

2.3 Current demand for social and affordable housing 15

2.4 Projected demand for social and affordable housing 29

2.5 Projected need by household type and housing service 43

2.6 Synthesis 44

3. WHY SHOULD COUNCIL GET INVOLVED? 45

3.1 Scope 45

3.2 Context 45

3.3 Creating city-wide value 47

3.4 Does a Capital City Council have a ‘special obligation’? 56

3.5 Synthesis 59

4. COUNCIL’S ROLE & POLICY LEVERS 61

4.1 Council’s role in affordable and social housing 61

4.2 The housing assistance spectrum 62

4.3 Policy levers and mechanisms 64

4.4 Implementation and impact 89

4.5 Synthesis 90

5. ECONOMIC CASE FOR INTERVENTION 91

5.1 Property market impacts of inclusionary requirements 91

5.2 Cost benefit analysis of mandatory affordable housing requirements 104

5.3 Synthesis 125

6. POLICY TARGETS FOR CITY OF MELBOURNE 126

6.1 Needs-based target: the residual target method 126

6.2 Precedent-based target 129

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

1

ABBREVIATIONS AND KEY TERMS

Abbreviation

Term

BCR

Benefit Cost Ratio

CBA

Cost Benefit Analysis

FAR

Floor Area Ratio

FAU

Floor Area Uplift

NPV

Net Present Value

RLV

Residual Land Value

SAH

Social and Affordable Housing

Housing Type

Description

Emergency Shelters /

Crisis Accommodation

Very short term accommodation, which includes additional support for the

resident during their stay.

Transitional Housing

Medium-term accommodation, which often includes support services for

residents.

Supported Housing

Long-term accommodation for people with high needs for support/care (e.g.

people with disability or elderly)

Social Housing

Long-term accommodation, including both public housing (government

owned) and community housing (housing association owned).

Affordable Rental

Housing

Rental housing which is affordable (within 30% of income) for households on

a moderate income or lower

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

2

SUMMARY

What is affordable housing?

This report focusses on the current and projected need for affordable rental housing in the

City of Melbourne (CoM). Also investigated are the Inner Metro Partnership (IMP) and the

Inner Melbourne Action Plan (IMAP) plus Moonee Valley regions.

The definition of affordable housing used in the report follows that set out in the Planning

and Environment Act, except that home owning or home buying households are excluded.

As shown in the following diagram, the scope of affordable housing adopted here includes but

extends beyond social housing but is nonetheless limited to very low, low and moderate

income rental households.

There is an alarming shortfall in affordable rental housing in the City

There is a current aggregate need for social and affordable housing in the City of Melbourne

for at least 9,436 units. This largely excludes student households and can, therefore, be

regarded as a lower bound estimate.

Current supply, measured by the stock of social housing in the City of Melbourne, is around

3,970 units. Therefore, the City of Melbourne has a deficiency in its social and affordable

All housing in City of Melbourne

Affordable housing

Affordable rental

housing

Social

housing

Available to households on

incomes up to $61k

(singles),

$91k (couples) and $127k

(families)

Rental or ownership tenure

Private or public landlord

(Priority access) available to

households on incomes up to

$29k

(singles), $50k (couples)

and $52k (families)

Stock owned by State or

Registered not for profit

providers

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

3

housing infrastructure of some 5,500 units. At a nominal acquisition cost of $0.5 million per

unit, this represents a $2.75 billion infrastructure deficit.

As with any other form of infrastructure, the need for social and affordable in the City of

Melbourne will increase with population growth. Future need will also be affected by

property market trends and patterns of income growth. SGS estimates that if there is no

addition to the City’s social and affordable housing stock, the shortfall in these dwellings will

grow to between 16,900 and 29,700 units by 2036 depending on the share of metropolitan

growth in affordable housing need which is assigned to the Melbourne local government area

(LGA).

Our estimates of social and affordable housing need separately identify the requirements of

‘Key Workers’. Depending on the share of the metropolitan pool of required Key Worker

housing which is assigned to the City of Melbourne, the projected need for this sector of

rental accommodation in the City in 2036 ranges between 2,500 and 7,900 dwellings.

To meet total projected demand for social and affordable housing in the City of Melbourne,

between 13.3 per cent and 21.5 per cent of the City’s total dwelling stock in 2036 would need

to be affordable rental housing as per the definition in the Planning and Environment Act.

Currently, affordable rental represents less than 6 per cent of all housing in the City of

Melbourne.

The City of Melbourne has a special role to play in meeting this need

The City of Melbourne has undergone transformative change since the 1990s transitioning

from being largely a location for business and workers to a thriving hub of cultural, social and

economic activity. This change, while positive, has held consequences for the affordability of

housing across the municipality. Those who cannot afford the rising housing costs are forced

to relocate to more affordable locations, increasingly causing a spatial patterning across

metropolitan Melbourne according to wealth and socio-demographic status. For many who

continue to live in the City of Melbourne (for a variety of reasons including, work, education,

social connections etc.), the rising cost of housing places increasing pressure on their health

and wellbeing.

By addressing affordable housing need in the City of Melbourne, Council can generate several

key benefits for its community by:

▪ Mitigating existing and future issues related to key worker retention in the central

city, thereby strengthening local business and overall economic efficiency.

▪ Achieving deeper and more genuine diversity through the provision of a greater

range of housing types, tenures and prices. This is anticipated to attract creative

talent (and business) and enhance Melbourne’s global reputation as a cultural and

creative hub.

▪ Enhancing opportunities for innovation by providing housing suitable for early career

entrepreneurs and research workers within education and research agglomerations.

▪ Addressing social injustice and enhancing equity resulting from locational

disadvantage and spatial socio-economic segregation.

There are several policy levers available to Council but no quick fixes

To address the considerable and rapidly growing shortage of social and affordable housing in

the City of Melbourne, Council would need to resolve these policy questions:

▪ What role to play, from hands-off advocacy through to direct investment in social

housing?

▪ Who to target with this policy effort, from those in or at risk of homelessness through

to ‘key’ and creative workers?

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

4

▪ How to deliver the adopted social and affordable housing aspirations via regulatory,

partnership and investment levers?

The levers which Council might apply to advance affordable housing supply in the City of

Melbourne can be grouped into three overlapping categories.

The ‘regulation’ group of interventions includes various mechanisms available to Council

under the Planning and Environment Act. These cover both voluntary and quasi-mandatory

arrangements whereby proponents provide affordable and social housing units or cash in lieu

in return for the awarding of development rights.

In the ‘partnership’ group of interventions, Council would work with the private sector or

community sector proponents to help them achieve affordable and social housing outcomes.

Examples include brokerage of partnerships between corporate developers and registered

community housing providers where the former are self-motivated to include affordable

housing in their projects. Similarly, Council might assist private sector proponents trial or

demonstrate innovative projects which improve affordability, like build to rent housing or

providing affordable rental on community trust land. Another important example is where

Council works with the State Government to improve the housing yield from public housing

assets.

The ‘investment’ group of interventions would see Council applying its own assets – whether

this be cash, land or underwriting capacity – to directly generate an expansion of social and

affordable housing in the City. By way of example, Council has, in the past, provided buildings

for permanent or temporary use as homeless accommodation. Providing relief from rates

and various council charges (including infrastructure and open space contributions) is another

form of ratepayer investment in affordable and social housing.

Specific mechanisms in each of these groups are summarised in the following chart.

Investment

Partnerships

Regulation

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

5

Some of these mechanisms are relatively readily applied in the City of Melbourne because

Council has the authority to move in its own right. Others are dependent on the State

Government and other parties providing the required authorising environment. For example,

there is no current mechanism in the Victoria Planning Provisions for the enforcement of

mandatory inclusion of affordable housing in new developments in the City of Melbourne,

although several policy statements suggest the State Government may consider enabling

reforms in this area.

As well as their capacity for successful implementation within a reasonable period (say two

years), the mechanisms can also differentiate in terms of the quantum of affordable housing

they are likely to generate over. The chart below shows SGS’s assessment of housing yield

versus ease of implementation for each of the listed mechanisms.

The array of policy levers open to Council is extensive, but no single mechanism can be

expected to make a major dent in the level of need by itself. While the State Government has

clarified the planning system can and should have a role in affordable housing provision, it is

PARTNERSHIP

INVESTMENT

REGULATION

Ad hoc voluntary agreements at

Planning Permit stage enforced

via s173 of the Planning &

Environment Act

Voluntary (s173) agreements at

Planning Permit stage backed by

strategic policy built into the

Melbourne Planning Scheme

Mandatory inclusionary

requirements at Planning Permit

stage

Floor area uplift in return for

provision of social and affordable

housing (value capture)

Uniform value capture provisions

incorporated into Planning

Scheme amendment

Planning waivers and concessions

in return for provision of

affordable and social housing

Facilitated redevelopment of

(State) public housing assets

Facilitation of innovative

affordable housing product -

Build to Rent

Facilitation of innovative

affordable housing product -

Rental housing on Community

Land Trust sites

Information and brokerage to

connect developers to registered

social housing providers

Vesting of Council land and

buildings for social and affordable

housing

Provision of an annual or one off

cash investment in social and

affordable housing provision

Waiver of rates and charges to

support social and affordable

housing projects

Establishment of a Trust to

receive and deploy affordable

housing contributions and Council

cash investments

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

6

yet to endorse mechanisms such as mandatory inclusionary zoning and development licensing

arrangements that could bolster the flow of social and affordable housing in Melbourne.

Intervention by Council is economically warranted

If Council had a means of enforcing affordable housing contributions via the planning system,

and it chose to apply such a tool, the impact on the local property market would depend on

the scale of the mandatory requirement.

Developers establish the maximum price they are willing to pay for a site by deducting their

required margin for profit and risk plus all their costs, including development contribution

liabilities, from their expected disposal value for the newly constructed dwellings and other

floorspace in the planned project. So long as this ‘residual land value’ (RLV) is greater than

the land seller’s minimum acceptable price, the project is viable and will proceed (see left-

hand panel in the diagram below).

Developers are ‘price takers’ not ‘price makers’. If confronted with a mandatory inclusionary

zoning requirement, developers will reduce their offer price for the sites in question. After

this reduction, if the RLV is still greater than the land owner’s minimum price, the project will

remain viable. Conversely, if the land price is pushed below the seller’s minimum acceptable

price, the project will not be feasible on that site and the proponent will need to look

elsewhere for a suitable development opportunity (see right-hand panel in the diagram

below). Over time, as dwelling prices increase, developers may be able to pay higher prices

for land and bring some sites, which were previously unviable for development, back into

consideration.

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

7

Introducing mandatory inclusion of affordable housing in the City could see the withdrawal of

a proportion of sites that would otherwise be available for development. The question is

whether there would be sufficient sites still available for viable development to fulfil

projected total housing requirements in the City.

SGS’s analysis shows that a mandatory requirement of up to 10 per cent could be supported

without choking off the required housing supply.

The analysis also shows that while some landowners will suffer a loss of value in their

property, mandatory requirements would deliver a strong net benefit for the whole

community.

SGS performed an economic evaluation of mandatory inclusionary affordable housing, on a

per dwelling basis, using conventional cost benefit analysis as prescribed in the State

Government state public finance guidelines. On the cost side, the analysis considered

dwelling construction costs, maintenance and operating costs and reduction in RLV. The

offsetting benefits included health cost savings, reduced domestic violence, reduced costs of

crime, enhanced human capital, worker retention, educational benefits, improved community

pride and social justice, retained cultural value, enhanced social capital and the gain in

housing services.

Over 20 years and using a commercial discount rate of 7 per cent the analysis returned a

benefit cost ratio of more than 3:1. That is, community benefits valued at more than $3 were

generated for each $1 of cost incurred by all parties in the implementation of mandatory

inclusionary requirements.

In this sense, this intervention is economically warranted.

Council requires an ambitious but achievable target for its policy efforts

Depending upon its appetite for involvement in the social and affordable housing supply

problem in the City of Melbourne, Council will be working in partnership with other spheres

of governance to greater or lesser degrees. A supply target for Council’s efforts as part of any

wider response may be required.

This supply target can be set in one of two ways; as a residual of what the other levels of

government deliver versus measured need; and extrapolation of precedents from other local

government policies. Given the scarcity of new supply known to be coming from the State

and Commonwealth Governments, the former approach would leave Council with a very high

target of almost 23,000 additional affordable housing units by 2036. The latter (extrapolation

of precedents) approach yields a range of targets the upper end of which is 8,800 additional

$

Land seller's minimum

acceptable price

Reduction in residual land

value

$

Mandatory AH

Land seller's minimum

acceptable price

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

8

units by 2036 for social and affordable housing. This would seem to be both ambitious and

realistic, given the leadership role and endowments of a capital city council. In addition, this

report proposes that Council adopt a target for crisis and transitional housing provision of

1,423 beds by 2036.

Broken down by housing type, the targets for the City of Melbourne are summarised as:

▪ Social housing (owned and operated by the State or registered community providers,

and accommodating mainly low and very low income households with marginal

involvement in the workforce)

▪ 7,527 additional dwellings by 2036

▪ Affordable housing (supplied by a number of different providers and various models

and housing low to moderate income households, including Key Workers, with

relatively shallow subsidies)

▪ 1,273 additional dwellings by 2036

▪ Crisis and transitional housing

▪ achieve a stock of 1,423 beds in the City by 2036

Assuming an affordable housing provision rate of 10% operated via some form of mandatory

requirement and further assuming an implementation ramp up period that sees this policy

taking effect from 2021, we have estimated that Council could deliver in the order of 4,300

affordable dwellings via this inclusionary approach. The balance of the 8,800 additional units

might be met via floor area uplift mechanisms, direct investment or through Registered

Housing Associations leveraging gifted stock to acquire additional dwellings.

The task of responding to the need for social and affordable housing in the City is significant.

We have estimated the aggregate requirement for the City of Melbourne local government

area in 2036 as almost 30,000 (additional) dwellings. The combined efforts of Council and

other spheres of government are required to address this challenge.

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

9

1. INTRODUCTION

This section of the report describes the policy context for this study, outlines the

scope of our work and provides an overview of the report’s structure.

Background

New housing policy for Melbourne

The City of Melbourne (CoM) is continuing to evolve its suite of planning, investment and

advocacy policies for the housing ‘system’ of the municipality. Council wants to see housing

outcomes in line with its vision for a sustainable, inclusive and prosperous Melbourne.

The City’s flagship housing policy document – Homes for People – is due for review, with its

nominated tenure – 2014-2018 – now expired. There have been significant changes in

context since Council adopted this policy. For example, the State Government released the

first ever integrated housing policy for the state – Homes for Victorians (HfV) – in March

2017. The refreshed metropolitan planning strategy – Plan Melbourne – includes a strong

focus on social and affordable housing, committing government to a more proactive use of

the planning system in generating affordable and social housing supply. The Planning and

Environment Act 1987 (the Act) has duly been amended to put beyond doubt that land use

and development regulation in Victoria may be applied to this purpose. As part of this

reform, clear definitions of affordable housing have been disseminated, with relevant income

bands nominated. We are now beginning to see these reforms in practical planning practice.

Amendment C270 (Am C270) to the Melbourne Planning Scheme and GC81 covering

Fishermans Bend variously contain a mix of value capture and voluntary mechanisms whereby

development proponents contribute to social and affordable housing outcomes.

It is fair to say that the housing policy ‘ship is beginning to turn’ in Victoria and Australia.

However, policy settings, and more importantly, investment in social and affordable housing,

at the Commonwealth and State levels remain grossly inadequate.

Commonwealth and state context

The contemporary framework for providing social and affordable housing is vastly different

from that which held sway in Australia and Victoria for many decades following the first

Commonwealth State Housing Agreement struck in 1945. Commonwealth capital funding for

providing social housing has all but withered, with Canberra implicitly favouring ‘safety net’

programs and rental assistance. State Government policy has followed a similar trajectory. It

is only since the adoption of the HfV package (and subsequent election promises from the

current government) that we have seen renewed interest in social housing by the State

Government.

With the virtual cessation of investment in (net) social housing expansion in the mid 1980s –

save for a temporary surge during the post global financial crisis (GFC) stimulus program of

the Commonwealth – Victoria’s and Melbourne’s housing supply has become dangerously

unbalanced. By any measure – waiting lists, levels of post-rent poverty and the proportion of

social housing to total housing – the shortage of affordable housing in the state is now

counted in the many tens of thousands. To the ordinary citizen, this manifests in escalating

rates of extreme homelessness, i.e. sleeping rough. But this is only the tip of the iceberg, with

large numbers of households suffering dislocation from education and job opportunities,

stress-related mental health illnesses and, indeed, violence.

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

10

The prospective framework for a revitalised social and affordable housing policy for

Melbourne and the state more generally is starting to become clear, based on the reforms

and initiatives noted above. We can expect or, perhaps, hope for:

▪ A gradual increase in the direct investment by the State and Commonwealth

Governments in social housing provision focussed, initially, on households in extreme

need, for example, those exposed to the risk of family violence

▪ Reinstating models like NRAS, which seek to leverage private investment in

affordable housing by bridging the ‘return gap’ between rents within the means of

moderate and lower income groups and commercially viable rents

▪ Growing use of new commercial models which enable more affordable and secure

rents premised on a change in the cost base, for example, build-to-rent and various

land trust arrangements

▪ Greater use of value capture arrangements such as Am C270 and the GC81 social

housing uplift requirements whereby proponents must purchase additional

development rights above nominated thresholds, through the provision of social

housing and other public benefits

▪ Greater use of affordable housing targets ‘with teeth’ as per the 6 per cent goal in

Fishermans Bend (also applied via GC81), and, perhaps

▪ Applying broad based, mandatory inclusionary zoning, pending the lessons from the

State Government’s piloting of the impacts of such requirements on its own land.

Purpose of this study

The City of Melbourne’s planning for a just, sustainable and prosperity-supporting housing

system in the City needs to anticipate this new policy environment. A good place to start is to

understand the current and projected need for affordable (including social) housing in the

City. With this key parameter established, Council can contemplate the appropriate targets

for affordable housing in the City, the various means by which the targets might be advanced

and the consequences – both positive and negative – of reaching or falling short of these

targets.

The brief issued by Council for this study called for research on these issues, to establish a

sound evidence base on which a new municipal housing policy might be developed.

approach to the study

SGS’s approach to the brief was, in part, guided by the principle that affordable housing

should be treated as a form of essential infrastructure in the planning and city building

process. That is, it should not be characterised as a discretionary social or welfare program.

Affordable housing, including social housing, is critical to the functionality of local labour

markets and it is a pre-requisite for neighbourhoods and cities that are sustainable (in the

social dimension of that word) and resilient. Accordingly, planning for affordable housing

should follow similar disciplines as those applied to other forms of social and economic

infrastructure. It should be based on projected needs taking a suitable long term view.

A second principle guiding our approach to the brief is that of subsidiarity in delivering this

essential infrastructure. As a pre-eminent planning authority for its jurisdiction, the City of

Melbourne must play a key role in identifying, measuring and locating the need for affordable

housing, in the same way it does for other forms of infrastructure. However, how this need is

fulfilled is a shared responsibility across the three spheres of governance.

As outlined above, the housing policy landscape has shifted significantly over the past decade.

The array of affordable housing supply tools available to Council and the actions expected of

it have expanded. This is particularly so in respect of planning mechanisms covering value

capture and various versions of inclusionary zoning. This does not mean, however, that the

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

11

City of Melbourne can be expected to fully meet identified affordable housing needs from its

policy levers and resources. Ideally, it would play a support role to re-invigorated and greatly

expanded social and affordable housing programs operated by the State and Commonwealth

Governments.

Structure of the report

The report is set out in six chapters. Following this introduction, Chapter 2 provides an

assessment of the need for social and affordable housing in the municipality of Melbourne, as

derived from an analysis of need at the metropolitan level. This discussion covers definitions

of housing need and the assumptions and analytical methods applied by SGS to arrive at a

range of discrete estimates of the shortfall in social and affordable housing in the municipality

as at 2016 and 2036.

Having measured aggregate need for social housing in the City, Chapter 3 explores the

rationale for Council involvement in meeting this need, recognising that this has not been a

mainstream function of local government in Victoria in the past. This rationale is examined

from many perspectives including the value that can be created for the wider City of

Melbourne community were the City to bring about a greater stock of social and affordable

housing versus what might happen under a passive policy scenario. Also canvassed is City of

Melbourne’s special obligation to create opportunities for the most marginalised in the

community given that the City is the beneficiary of disproportionate taxpayer investment in

infrastructure and services. Finally, Chapter 3 outlines the types of households that would

benefit most from a pro-active and escalated City of Melbourne policy on social and

affordable housing provision in the City.

Chapter 4 examines the policy levers and tools Council could apply were it of a mind to

advance affordable and social housing provision in the City. The chapter covers:

▪ an overview of each mechanism/tool

▪ the benefits, scale of impact and drawbacks of each tool

▪ the household types most likely to be benefited by each tool

▪ how the tools might be implemented by Council under current legislation and state

policy settings, and

▪ the subsidy (if any) required to enable the tool to work for various household types.

In contemplating whether, and to what extent, these tools might be applied, Council will be

interested in their impact on development activity in the City and whether they would

generate a net community benefit, that is, the value they create for the City of Melbourne

community and the state as whole is greater than the costs they would generate. These

questions are taken up in Chapter 5 of the report.

Assuming that Council is interested in meeting housing need in the City, while recognising this

need has been allowed to grow to extreme proportions by the State and Commonwealth

Governments, the question arises as to the target the City of Melbourne might adopt (driven

by its own efforts) in expanding this stock of housing in the City by 2036. Various methods by

which the aggregate need identified in Chapter 2 might be scaled down to form a target for

Council’s housing policy are canvassed in Chapter 6. This final chapter also discusses the

types of packages of levers and mechanisms Council would need to apply to meet either a

high or modest municipal target for social and affordable housing.

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

12

2. MEASURING AFFORDABLE

HOUSING NEED IN MELBOURNE

This section provides an assessment of the need for social and affordable housing

in the municipality of Melbourne, as derived from an analysis of need at the

metropolitan level. This discussion covers definitions of housing need and the

assumptions and analytical methods applied by SGS to arrive at a range of

discrete estimates of the shortfall in social and affordable housing in the

municipality as at 2016 and 2036. The Inner Metro Partnership (IMP) area and

Inner Melbourne Action Plan (IMAP) plus Moonee Valley region are also

examined.

2.1 Scope and definitions

Focus on rental affordability

The focus of this study is the need for affordable and appropriate rental accommodation for

very low, low, and moderate income households in the City of Melbourne.

Mortgage stress and opportunities for households to gain affordable access to home

ownership are not within the scope of this report. This is not to diminish these issues. Rather

this scope delineation recognises the greatly different types of policy responses required to

support home ownership as distinct from securing an adequate supply of accommodation for

households that are effectively confined to the rental market for the time being if not

indefinitely.

A need or a unit of ‘demand’ for social and affordable housing arises when a moderate or

lower income household confronts moderate or severe rental stress, as elaborated in the text

box below. A state of homelessness, including marginal accommodation, signifies a need for

social and affordable housing. Households in existing social housing must also be included in

the demand for this form of housing, particularly in the contemporary context where,

because of severe shortages, social housing is effectively reserved for households on very low

incomes that would otherwise face serious rental stress in the private market.

Transitional versus permanent demand for social and affordable housing

Some households may find themselves in temporary or intermittent rental stress pending

their employment and income circumstances. Others may suffer prolonged or indefinite

rental stress. The measure of demand for affordable and social housing at any given point in

time will include both those in permanent and temporary need. Discounting the measured

requirement for social and affordable housing to account for households in transitional need

would provide misleading results. Those exiting a situation of rental stress will be replaced by

those entering this situation; in other words, a cross-sectional snapshot of demand for social

and affordable housing drawn from, say, Census data on rental stress, embodies the

dynamism in the housing careers of individual households.

That said, a degree of minor discounting – say 5 per cent or 10 per cent - may be justified in

recognition that some households in rental stress at any given time may have options to

autonomously relieve that stress, for example, by relying on their wider family to provide long

term accommodation.

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

13

Source: SGS Economics and Planning, 2019

Definition of affordable and social housing and relevant income bands

The definition of affordable and social housing used in this report is consistent with that set

out in the Planning and Environment Act 1987:

“affordable housing is housing, including social housing, that is appropriate for the

housing needs of very low, low, and moderate-income households”.

“Social housing”, in turn, is defined in the Housing Act 1983 as housing that is owned by the

Director of Housing (public housing) as well as housing that is owned or managed by

registered housing agencies (community housing).

Community housing providers are also registered and regulated by the state government

through a regulatory framework overseen and implemented by the Registrar of Housing.

The bands constituting the very low, low and moderate income households cited in the

Planning and Environment Act 1987 are established each year by order published in the

Government Gazette. The applicable ranges at the time of writing are set out in Figure 1

overleaf.

What is rental stress?

Rental stress is the situation where a moderate (or lower) income household’s rental

payments are so high that they must sacrifice on life’s necessities such as such as food,

health care, or education.

Moderate housing stress is when a household must spend more than 30 per cent of

their income on rent.

Severe housing stress is when a household must spend more than 50 per cent of their

income on rent.

Affordable housing is appropriate for very low, low and moderate-income households

in rental stress. It is not appropriate for high-income households because high housing

costs are unlikely to impact their ability to pay for necessities.

Housing

Costs

Disposable

Income

Housing

Costs

Disposable

Income

> 30%

Moderate Stress

> 50%

Severe Stress

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

14

FIGURE 1 OFFICIAL INCOME RANGES – ELIGIBILITY FOR AFFORDABLE HOUSING GENERATED UNDER THE

PLANNING AND ENVIRONMENT ACT 1987

Greater Capital City Statistical Area of Melbourne

Rest of Victoria

Source: Victoria Government Gazette No. S 256 Friday 1 June 2018

Social housing has its own set of income eligibility criteria, enabled by the Housing Act 1983.

These apply state-wide and are reproduced in the following table. Social housing eligibility

limits are somewhat tighter than those for the broader category of ‘affordable housing’ as

defined in the Planning and Environment Act 1987, especially where priority access to

accommodation is being sought by the applicant (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 2 ELIGIBILITY LIMITS – SOCIAL HOUSING

For inclusion on the general social housing wait list (register)

Annual income

Single adult

$52,156

Couple, no dependants

$79,820

Family with one or two parents and dependent children (2)

$107,640

For priority access

Single adult

$29,172

Couple, no dependants

$50,440

Family with one or two parents and dependent children (2)

$52,260

Source: Housing Vic ( https://housing.vic.gov.au/social-housing-eligibility#eligibility-criteria )

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

15

FIGURE 3 AFFORDABLE HOUSING IN CITY OF MELBOURNE

Source: SGS Economics and Planning, Vic Government websites

2.2 Method

SGS has estimated the ‘current’ (2016) and projected (2036) requirement for social and

affordable housing need in metropolitan Melbourne and in the City of Melbourne using its

Housing Assistance Demand (HAD) Model. The Inner Metro Partnership (IMP) Area (LGAs of

Melbourne, Yarra, and Port Phillip) and the Inner Melbourne Action Plan (IMAP) area plus

Moonee Valley (LGAs of Melbourne, Port Phillip, Stonnington, Yarra, Maribyrnong, and

Moonee Valley) are also examined. The original version of the HAD Model was commissioned

by the State Government to assist in the strategic planning of a range of housing services

including investment in social housing.

The Model is described in Appendix 1.

2.3 Current demand for social and affordable housing

Metropolitan Melbourne

SGS estimates that in 2016, the demand for social and affordable housing across metropolitan

Melbourne exceeded 231,000 households. As shown in Figure 4, this demand includes

individuals who are homeless (20,500), households who currently reside in social housing

(49,000), and households with moderate incomes (or lower) who are experiencing rental

stress (162,000).

All housing in City of Melbourne

Affordable housing

Affordable rental

housing

Social

housing

Available to households on

incomes up to $61k

(singles),

$91k (couples) and $127k

(families)

Rental or ownership tenure

Private or public landlord

(Priority access) available to

households on incomes up to

$29k

(singles), $50k (couples)

and $52k (families)

Stock owned by State or

Registered not for profit

providers

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

16

FIGURE 4: METROPOLITAN MELBOURNE DEMAND (HOUSEHOLDS) FOR SOCIAL AND AFFORDABLE HOUSING,

2016

Source: SGS Economics and Planning, 2019

Figure 5 presents a more detailed segmentation of these results, showing that demand for

social and affordable housing represents 13 per cent of all households. Households in the

private rental market earning very low incomes are worst affected, with 22 per cent requiring

assistance and over 60 per cent experiencing severe rental stress.

FIGURE 5: METROPOLITAN MELBOURNE HOUSING MARKET SEGMENTATION, 2016

Other

households

(a)

Moderate

rental

stress

(b)

Severe

rental

stress

(c)

Outside

private

market

(d)

Total

households

(a + b + c + d)

Quantum

of Demand

(b + c + d)

Demand

share of

total

households

Homeless

NA

NA

NA

20,429

20,429

20,429

100%

Living in social

housing

NA

NA

NA

48,978

48,978

48,978

100%

Very low

income

households

300,997

30,359

52,672

NA

384,027

83,031

22%

Low income

households

279,465

35,822

14,837

NA

330,124

50,659

15%

Moderate

income

households

320,328

23,577

4,564

NA

348,470

28,141

8%

Above

moderate

income

households

641,333

NA

NA

NA

641,333

0

0%

All households

1,542,123

89,758

72,073

69,407

1,773,361

231,238

13%

Source: SGS Economics & Planning, based on ABS Census 2016 and VIF 2016

Note: Other households includes both rental households who are not in rental stress and non-rental households, and does

not contribute to demand for social and affordable housing

For all the categories of demand considered above, Figure 6 shows that lone person

households form the largest component of demand, followed by one parent families. This is

particularly true of those suffering severe rental stress. Along with the results shown in Figure

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

17

5, this indicates that the largest share of demand is comprised of the most vulnerable

households – that is, those who have very low incomes, have lower income generation

potential (being single income households at most), and have dependents (i.e. lone parent

families).

FIGURE 6: DEMAND (HOUSEHOLDS) FOR SOCIAL AND AFFORDABLE HOUSING (2016) BY HOUSEHOLD TYPE

Note: ‘Other family’ refers to related individuals who are not parents/children (e.g. siblings, grandparents, uncles/aunts)

Source: SGS Economics and Planning

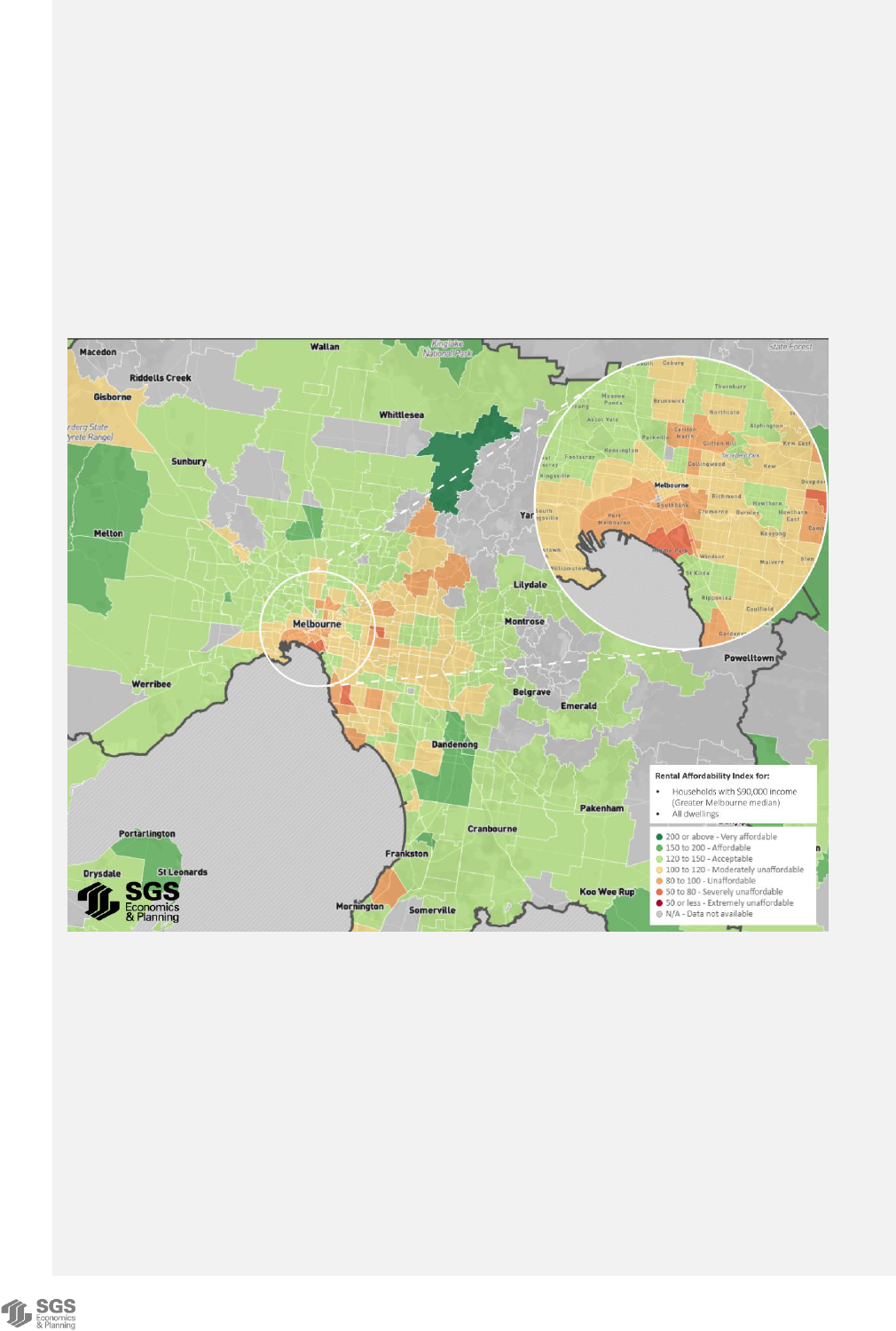

The figures below present the spatial distribution of existing demand for social and affordable

housing across metropolitan Melbourne, disaggregated by the categories considered in Figure

5.

Homeless persons and those living in social housing (Figure 7) are most common in inner

Melbourne (LGAs of Melbourne, Yarra, and Port Phillip) and the outer south east (LGAs of

Greater Dandenong and Casey). However, it is important to note that, compared to other

cohorts, the locations of these groups are not as strongly determined by individual choice.

Rather, factors such as the location of existing social housing stock or homelessness services

play a significant role.

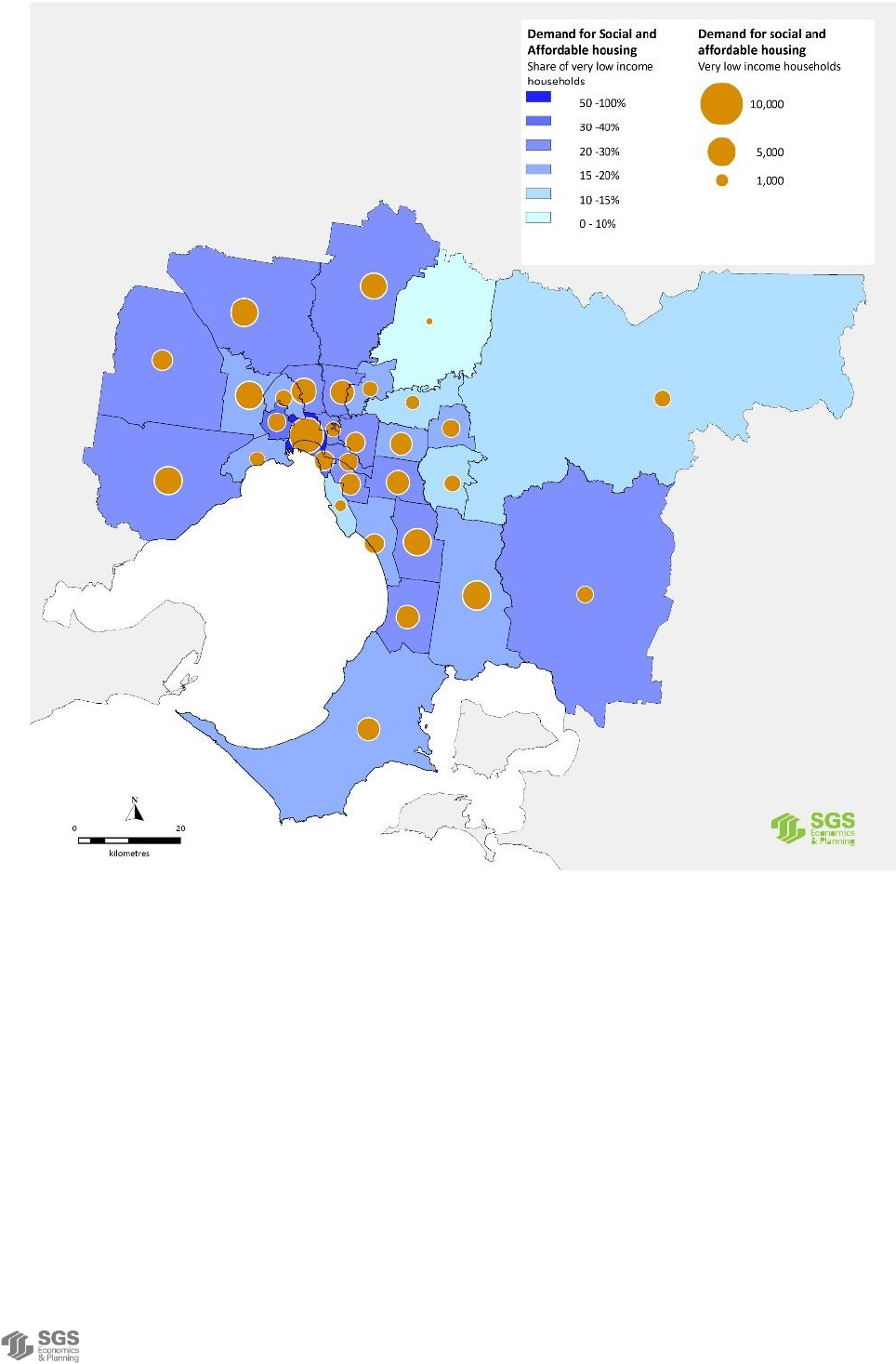

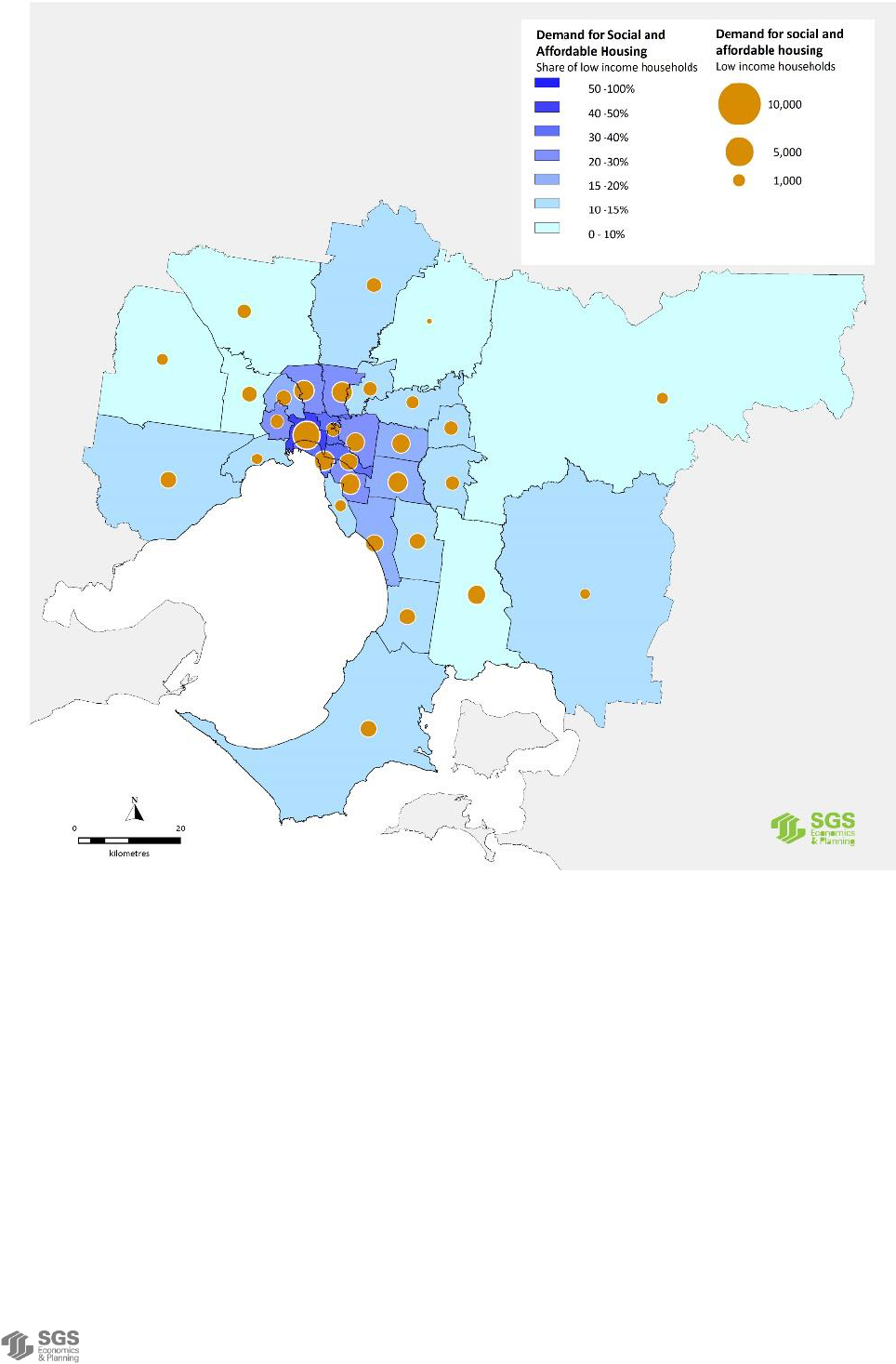

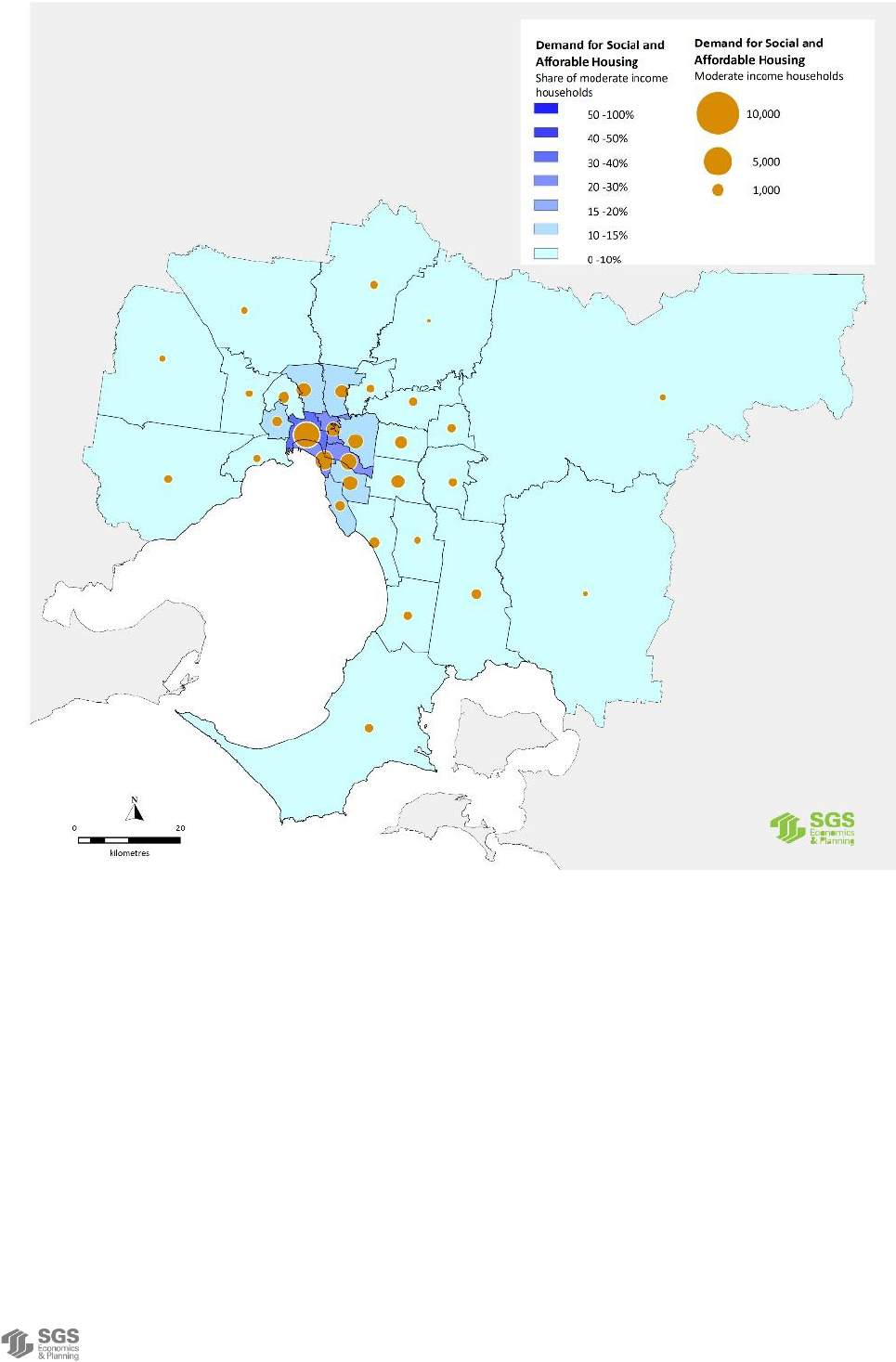

Figure 8, Figure 9, and Figure 10 present the spatial distribution of demand for rental

households in the very low, low, and moderate income groups respectively. In each map, the

size of the bubble represents the quantum of demand, while the shade of the region shows

the share of households (within each income group) which require social and affordable

housing.

Unsurprisingly, the quantum and share of demand for all income groups is greatest in central

Melbourne, and the City of Melbourne in particular. This is best illustrated by Figure 10, which

shows that almost 40 per cent of households on moderate incomes experience rental stress

within the City of Melbourne. This reflects two driving factors; rents which are beyond the

affordable threshold for households on moderate incomes or less, and the decision of many

these households to bear rental stress to live in these areas.

While very low income households have the highest rate of demand within the City of

Melbourne (over 50 per cent), this does not improve significantly in outer municipalities, with

over 20 percent of very low income households requiring social and affordable housing in

both the middle ring and growth areas of Melbourne.

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

18

FIGURE 7: HOUSEHOLDS LIVING IN SOCIAL HOUSING AND HOMELESS HOUSEHOLDS (INDIVIDUALS) BY LGA

(2016)

Source: SGS Economics and Planning, based on ABS Census 2016 and VIF 2016

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

19

FIGURE 8: VERY LOW INCOME RENTAL HOUSEHOLDS - DEMAND BY LGA (2016)

Source: SGS Economics and Planning, based on ABS Census 2016 and VIF 2016

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

20

FIGURE 9: LOW INCOME RENTAL HOUSEHOLDS - DEMAND BY LGA (2016)

Source: SGS Economics and Planning, based on ABS Census 2016 and VIF 2016

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

21

FIGURE 10: MODERATE INCOME RENTAL HOUSEHOLDS - DEMAND BY LGA (2016)

Source: SGS Economics and Planning, based on ABS Census 2016 and VIF 2016

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

22

City of Melbourne

The demand for social and affordable housing within the City of Melbourne, by income group

and household type are show in Figure 11 and Figure 12. Over 20,000 households or 30 per

cent of all households are in need

1

of housing assistance, which is high when compared to the

metropolitan average of 13 per cent. This is particularly striking when considering the income

profile of the municipality, with 46 per cent of households earning above moderate incomes,

compared to the metropolitan share of 36 per cent.

Figure 13 to Figure 16 present the same analysis for the Inner Metro Partnership (IMP) region

and Inner Melbourne Action Plan (IMAP) region plus Monee Valley. Existing need within these

areas is less acute (although still greater than the metropolitan average), with 24 per cent and

20 percent of households in need of housing assistance within the IMP and IMAP regions

respectively.

FIGURE 11: CITY OF MELBOURNE HOUSING MARKET SEGMENTATION BY INCOME GROUP, 2016

Other

households

Moderate

rental

stress

Severe

rental

stress

Outside

private

market

Total

households

Quantum

of

Demand

Demand

share of total

households

Homeless

NA

NA

NA

1,725

1,725

1,725

100%

Living in social

housing

NA

NA

NA

3,970

3,970

3,970

100%

Very low income

households

6,049

772

5,706

NA

12,526

6,477

52%

Low income

households

4,318

1,998

2,217

NA

8,533

4,215

49%

Moderate income

households

6,570

2,985

897

NA

10,452

3,882

37%

Above moderate

income households

31,392

NA

NA

NA

31,392

0

0%

All households

48,328

5,755

8,820

5,695

68,598

20,269

30%

Source: SGS Economics and Planning, based on ABS Census 2016 and VIF 2016

Note: Other households includes both rental households who are not in rental stress and non-rental households, and does

not contribute to demand for social and affordable housing

FIGURE 12: CITY OF MELBOURNE HOUSING MARKET SEGMENTATION BY HOUSEHOLD TYPE, 2016

Other

households

Moderate

rental

stress

Severe

rental

stress

Outside

private

market

Total

households

Quantum

of

Demand

Demand

share of total

households

Couple family with

children

5,818

377

279

377

6,852

1,033

15%

Couple family with

no children

14,574

1,322

1,151

276

17,323

2,749

16%

One parent family

2,092

246

337

882

3,556

1,464

41%

Other family

1,921

400

555

99

2,975

1,054

35%

Group household

6,268

1,366

2,458

209

10,301

4,033

39%

Lone person

household

17,655

2,044

4,039

3,853

27,590

9,935

36%

All households

48,328

5,755

8,820

5,695

68,598

20,269

30%

Source: SGS Economics and Planning, based on ABS Census 2016 and VIF 2016

1

Note that this includes 1,725 homeless persons and 3,970 households already living in social housing

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

23

Note: Other households includes both rental households who are not in rental stress and non-rental households, and does

not contribute to demand for social and affordable housing

FIGURE 13: INNER METRO PARTNERSHIP (IMP) REGION HOUSING MARKET SEGMENTATION BY INCOME

GROUP, 2016

Other

households

Moderate

rental

stress

Severe

rental

stress

Outside

private

market

Total

households

Quantum

of

Demand

Demand share

of total

households

Homeless

NA

NA

NA

3,690

3,690

3,690

100%

Living in social

housing

NA

NA

NA

11,540

11,540

11,540

100%

Very low

income

15,093

1,754

8,616

NA

25,464

10,371

41%

Low income

11,374

4,100

3,790

NA

19,264

7,890

41%

Moderate

income

17,022

5,837

1,667

NA

24,526

7,504

31%

Above

moderate

income

84,085

NA

NA

NA

84,085

0

0%

All households

127,575

11,691

14,073

15,230

168,569

40,994

24%

CoM share of

IMP Region

38%

49%

63%

37%

41%

49%

Source: Source: SGS Economics and Planning, based on ABS Census 2016 and VIF 2016

Note: Other households includes both rental households who are not in rental stress and non-rental households, and does

not contribute to demand for social and affordable housing

FIGURE 14: INNER MELBOURNE ACTION PLAN (IMAP) PLUS MOONEE VALLEY HOUSING MARKET

SEGMENTATION BY INCOME GROUP, 2016

Other

households

Moderate

rental

stress

Severe

rental

stress

Outside

private

market

Total

households

Quantum

of

Demand

Demand share

of total

households

Homeless

NA

NA

NA

5,201

5,201

5,201

100%

Living in social

housing

NA

NA

NA

17,570

17,570

17,570

100%

Very low

income

33,404

3,617

12,663

NA

49,683

16,280

33%

Low income

26,446

7,225

5,306

NA

38,978

12,532

32%

Moderate

income

36,253

8,558

2,203

NA

47,014

10,761

23%

Above

moderate

income

146,081

NA

NA

NA

146,081

0

0%

All households

242,185

19,400

20,172

22,771

304,528

62,343

20%

CoM share of

IMAP (plus

Moonee Valley)

20%

30%

44%

25%

23%

33%

Source: Source: SGS Economics and Planning, based on ABS Census 2016 and VIF 2016

Note: Other households includes both rental households who are not in rental stress and non-rental households, and does

not contribute to demand for social and affordable housing

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

24

FIGURE 15 INNER METRO PARTNERSHIP (IMP) REGION HOUSING MARKET SEGMENTATION BY HOUSEHOLD

TYPE, 2016

Other

households

Moderate

rental stress

Severe rental

stress

Outside

private

market

Quantum of

Demand

Demand

share of total

households

Couple family

with children

19,807

742

575

1,064

2,381

11%

Couple family

with no children

38,134

2,596

1,939

843

5,378

12%

One parent

family

6,233

651

700

2,760

4,111

40%

Other family

3,261

599

702

263

1,564

32%

Group

household

15,623

2,551

3,547

436

6,534

29%

Lone person

household

44,517

4,551

6,610

9,865

21,026

32%

All households

127,575

11,691

14,073

15,230

40,994

24%

CoM share of

IMP Region

38%

49%

63%

81%

49%

0%

Source: SGS Economics and Planning, based on ABS Census 2016 and VIF 2016

Note: Other households includes both rental households who are not in rental stress and non-rental households, and does

not contribute to demand for social and affordable housing

FIGURE 16 INNER MELBOURNE ACTION PLAN (IMAP) PLUS MOONEE VALLEY HOUSING MARKET

SEGMENTATION BY HOUSEHOLD TYPE, 2016

Other

households

Moderate

rental stress

Severe rental

stress

Outside

private

market

Quantum of

Demand

Demand

share of total

households

Couple family

with children

53,630

1,532

1,039

1,623

4,194

7%

Couple family

with no children

68,796

4,374

2,912

1,296

8,582

11%

One parent

family

15,074

1,412

1,274

4,178

6,864

31%

Other family

5,358

868

877

404

2,148

29%

Group

household

23,676

3,809

4,506

641

8,956

27%

Lone person

household

75,650

7,406

9,564

14,629

31,599

29%

All households

242,185

19,400

20,172

22,771

62,343

20%

CoM share of

IMP Region

20%

30%

44%

56%

33%

0%

Source: SGS Economics and Planning, based on ABS Census 2016 and VIF 2016

Note: Other households includes both rental households who are not in rental stress and non-rental households, and does

not contribute to demand for social and affordable housing

These results are a robust estimate of the number of households within the categories which

constitute demand for affordable housing. However, this likely includes households who meet

the definition of being in rental stress but do not need to forego life’s necessities such as

food, health care and education, and therefore do not necessarily contribute to demand for

affordable housing. Examples of households that might fall into this category could include:

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

25

▪ Students with relatively low incomes but few other expenses or those who can draw on

savings or family support for the limited time during which they complete their education

▪ Working holiday makers (e.g. those who choose to pay high housing costs for the benefits

it provides, and often in the short term), and

▪ Households that are only temporarily in rental stress.

Determining which of these households genuinely contribute to demand for social and

affordable housing is difficult as more detailed information about incomes, external

assistance and expenditure are not available.

Students households, housing stress and demand for housing assistance

A consequence of having several major universities and vocational education and training

(VET) institutes in the City is that students form a large component of residents. In 2016, the

38,700

2

tertiary students living in the City constituted 32 per cent of the resident population.

Eighty-nine per cent of students study full-time. Most tertiary students reside in rental

properties as group households, while lone person households and couples with no children

are the next most common household types (see Figure 17). A significant number of students

(4,700 or 12 per cent) also reside in non-private dwellings. These are college residences,

boarding houses, and hotels/motels.

FIGURE 17: COUNT OF TERTIARY STUDENTS BY HOUSEHOLD TYPE IN THE CITY OF MELBOURNE (2016)

Source: SGS Economics and Planning, based on ABS Census 2016

While many households containing students experience rental stress (based on the

comparison of rental costs to incomes) it is likely that not all need of housing assistance. The

incomes of students may be supplemented by support from universities or family or from

savings. Furthermore, it might be argued that some students choose temporary rental stress

willingly while completing studies to advance their careers. Accurately determining which

student households genuinely require affordable housing is difficult, due to the limitations of

available data to measure these characteristics. Figure 18 displays the locations of students

who live in private dwellings

3

in the City. This map suggests concentrations of students

residing in the CBD, City North, Parkville, and Kensington.

2

ABS Census 2016

3

While not explicitly addressed in Census definitions, purpose-built student accommodation (PSBA) is most likely recorded

as private accommodation

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

26

FIGURE 18: LOCATION OF TERTIARY STUDENTS LIVING IN PRIVATE DWELLINGS (2016)

Source: ABS Census 2016

Figure 19 shows students living in non-private dwellings, with the greatest concentration in

Parkville which includes the University of Melbourne residential colleges. Students in these

non-private dwellings are not included in the estimation of households in rental stress

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

27

FIGURE 19: LOCATION OF TERTIARY STUDENTS LIVING IN NON-PRIVATE DWELLINGS (2016)

Source: ABS Census 2016

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

28

Demand for social and affordable housing net of student households

The counts of student households in rental stress by household type are shown in Figure 20.

It is estimated that over 11,000

4

households with students in the City of Melbourne are in

rental stress. Consistent with Figure 17, which reports the living arrangements of the entire

student population, lone person households and group households make up the largest share

of tertiary student households in rental stress.

As discussed above, some of these households may not require affordable housing despite

being in rental stress. However, this distinction is both difficult to define and to measure.

Research conducted for the City of Sydney, which included student surveys and interviews

with student advocacy groups, found evidence supporting the need for affordable housing for

students. The findings highlight both the short and long term benefits (or disbenefits of a lack

of affordable housing options), such as:

▪ Students being productive members of the community, who contribute to the local

vibrancy and provide key services (e.g. hospitality, retail, childcare). A lack of

affordable housing options reduces their ability to live and work in the City

▪ High rent means that students have to work more, leaving less time to study. This has

negative impacts on their resilience, their mental health, and their ability to finish

their studies or study enough – directly opposing why they’re here

▪ Education is one of Australia’s top three international exports. Ensuring a competitive

housing offer is key to maintaining this

The final column of Figure 20 provides an adjusted measure of demand for social and

affordable housing which assumes that, for student households, only those containing

children require housing assistance

5

.

Based on this assumption, approximately 9,450 households of all types in the City of

Melbourne need social and affordable housing.

Although the base demand estimate (column 1) is likely to overstate demand, the adjusted

estimate, excluding the majority of student households, is highly conservative and could be

interpreted as the absolute lower bound estimate of true demand.

While assessing the detailed housing assistance needs of students, and government’s role in

providing this assistance, is beyond the scope of this study, it can be stated that student

demand is at most 11,000 dwellings. This means that the total existing demand for social and

affordable housing in the City of Melbourne lies between 9,400 and 20,000 dwellings.

4

See Appendix 2 for further detail

5

See Appendix 2 for further detail

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

29

FIGURE 20: HOUSEHOLDS IN RENTAL STRESS IN IN THE CITY OF MELBOURNE ADJUSTED FOR TERTIARY

STUDENTS (2016)

Demand for social

and affordable

housing

Tertiary student

households in rental

stress

Discount applied to

adjust demand total

Adjusted demand for

social and affordable

housing

Couple family

with children

1,033

228

0

1,033

Couple family

with no children

2,749

1,778

1,778

971

One parent

family

1,464

197

0

1,464

Other family

1,054

923

923

131

Group household

4,033

3,787

3,787

246

Lone person

household

9,935

4,345

4,345

5,590

All households

20,269

11,258

10,833

9,436

Source: SGS Economics and Planning, based on ABS Census 2016

2.4 Projected demand for social and affordable housing

Metropolitan Melbourne

Metropolitan Melbourne is expected to grow by almost 770,000 households between 2016

and 2036. Driven by an ageing population, lone person households will contribute the largest

share of this change, with a growth of over 240,000 households.

FIGURE 21: HOUSEHOLDS BY TYPE, 2016 - 2036

Source: SGS Economics & Planning, based on ABS Census 2016 and VIF 2016

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

30

FIGURE 22: FORECAST DEMAND (HOUSEHOLDS) FOR SOCIAL AND AFFORDABLE HOUSING, METROPOLITAN

MELBOURNE, 2016 - 2036

2016

2036

Change

AAGR

Couple family with children

29,274

39,282

10,008

1.5%

Couple family with no children

33,711

49,631

15,920

2.0%

One parent family

40,488

59,075

18,588

1.9%

Other family

5,266

7,026

1,760

1.5%

Group household

20,892

26,560

5,668

1.2%

Lone person household

101,608

156,467

54,859

2.2%

Total

231,238

338,040

106,802

1.9%

Very low income

152,438

223,573

71,135

1.9%

Low income

50,659

73,394

22,735

1.9%

Moderate income

28,141

41,073

12,932

1.9%

Total

231,238

338,040

106,802

1.9%

Source: SGS Economics and Planning, based on ABS Census 2016, VIF 2016, and City of Melbourne household forecasts

Assuming no changes to the existing market structure

6

(such as the distribution of incomes

and rents and the efficiency of matching between rental properties with households),

demand for social and affordable housing will grow by 107,000 over the 20-year period. By

2036, this will represent 13.3 per cent of all households. Figure 22 segments this demand

twice, once by household type and once by income group. Under this baseline scenario, the

greatest need will be expressed by lone person households and those on very low incomes.

A third segmentation of demand, which will influence the nature of social and affordable

housing required, is the presence of household members with special needs due to a

disability or mental health condition. These households are more likely to require greater

access to health services, public transport, and may require specialist dwelling forms.

These special needs households satisfy the following criteria

7

:

▪ They have one or more household members who, due to disability or mental illness,

are ‘profoundly limited in core activities’ (i.e. a person is unable to do, or always

needs help with a core-activity task such as communication, mobility or self-care)

▪ Have a low income (defined as falling within the bottom 40

th

percentile of equivalised

household income)

▪ Occupy a dwelling under a rental or rent-free tenure. This includes households

currently in social housing but excludes those in life-tenure arrangements such as

retirement villages (as these are similar to home ownership).

This does not represent all households with a member who has a disability, but rather the

groups which will be most vulnerable to homelessness, and in need of housing support with

special considerations.

Between 2016 and 2036 demand from this group will increase in line with population growth,

from 19,000 to almost 28,000 households. Although lone person households form the largest

component of this demand, a large share is also formed by one parent families.

6

Further detail provided in Appendix 1

7

These households are assumed to be a subset of the overall demand measured previously (i.e. 100 per cent overlap) and

cannot be further segmented by income groups. This is due to the use of an external data source to measure disability and

mental health conditions. Further detail provided in appendix

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

31

FIGURE 23: FORECAST DEMAND (HOUSEHOLDS) FOR SOCIAL AND AFFORDABLE HOUSING DUE TO DISABILITY

OR MENTAL HEALTH CONDITION, METROPOLITAN MELBOURNE, 2016 - 2036

2016

2036

Change

AAGR

Couple family with children

1,998

2,724

726

1.6%

Couple family with no children

411

649

238

2.3%

One parent family

7,587

10,762

3,175

1.8%

Group household

213

314

101

2.0%

Lone person household

8,876

13,349

4,473

2.1%

Total

19,084

27,797

8,713

1.9%

Source: SGS Economics and Planning, based on ABS Survey of Disability, Aged, and Carers (2015) and VIF 2016.

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

32

Distribution scenarios

The forecast demand for 338,000 social and affordable housing could be accommodated

across metropolitan Melbourne in a range of ways, based on factors such as maximising the

opportunities available to tenants, cost minimisation to providers, or integration with private

dwelling stock. This section considers four different approaches to distributing future

demand. The first is to simply weight the distribution of social and affordable housing to align

with the future population distribution; the second also uses a weighting method but carries

out the distribution for each household type in turn; the third also uses a household type

specific weighting method but excludes less accessible parts of the city from the distribution;

and the fourth includes a separate distribution procedure for the identified ‘Key Workers’

within the overall group of households forecast to be in need of affordable housing.

Each of these distribution scenarios are explained in the following pages.

Scenario 1 – Household (total) weighted distribution

Scenario 1 allocates future demand for social and affordable housing in alignment with the

total number of households across the municipalities of Melbourne. This results in the City of

Melbourne accommodating 6.2 per cent of metropolitan demand. This distribution will result

in spatial integration between social and affordable housing and households in the private

market and can be interpreted as a ‘fair share’ scenario.

Scenario 2 – Household (by type) weighted distribution

Scenario 2 refines the method used in Scenario 1. Here, future demand for social and

affordable housing generated by each household type is considered separately. The demand

for each household type is distributed in alignment with the number of households of that

type across the municipalities of Melbourne. This still represents a ‘fair share’ scenario but

avoids the misalignment of household types

8

that occurs under scenario 1.

Scenario 3 - Household weighted distribution in accessible locations

This scenario assumes that the future demand for social and affordable housing will be

excluded from areas of Melbourne which have a poor

9

level of accessibility to jobs and

services

10

. This is achieved using a measure known as effective job density, as shown below.

8

E.g. Casey has the greatest share of households in 2036, which are primarily family households. On the other hand, lone

person households form the greatest share of demand for social and affordable housing across metropolitan Melbourne.

Under Scenario 1, Casey would be allocated an inappropriately large amount of lone person household demand, which will

not occur under Scenario 2

9

Areas with an EJD in the lowest 25

th

percentile are excluded

10

This is based on the current (2016) state, and not a modelled future scenario (e.g. including future infrastructure)

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

33

FIGURE 24: EFFECTIVE JOB DENSITY (2016)

Source: SGS Economics and Planning

Figure 24 illustrates accessibility across metropolitan Melbourne in 2016, showing that the

central city and inner east perform best, while the western and northern growth areas have

poorer access to jobs and services.

WHAT IS EFFECTIVE JOB DENSITY?

EJD indicates the accessibility to jobs in a given area based on the location of

jobs, both in the area and how long it takes to get to other jobs across

Melbourne. It is linked to the transport networks and infrastructure, a high EJD

can be a result of having a large pool of employment nearby or being well

connected to more distant employment.

For a given spatial zone,

Where:

−

−

−

−

−

−

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

34

FIGURE 25: SCENARIO 3 - DISTRBUTION OF DEMAND FOR LONE PERSON HOUSEHOLDS (2036)

Source: SGS Economics and Planning

In Scenario 3, the geographic scope for allocating demand is restricted by excluding areas

which have an EJD in the lowest quartile. Next, demand for social and affordable housing is

allocated based on the relative quantum of households (i.e. all households, regardless of

whether they require affordable housing) within this area. Figure 25 presents this restricted

geographic scope (i.e. the yellow shaded area has relatively low accessibility), and the

weighting distribution for lone person households

11

within the area.

Scenario 4 – Key worker adjusted distribution

This scenario is designed to allocate demand for affordable housing in a manner which

prioritises the needs of Key Workers. That is, it attempts to predict the demand for social and

affordable housing spatially to align with the workplaces of Key Workers.

An integral component of this analysis is the definition of what constitutes Key Workers.

While the term ‘key worker’ is widely used, it has no accepted definition, and its use can lead

to confusion. It is often interpreted as referring to workers that provide essential services

(e.g. police officers, fire services, nurses and teachers). However, unless early in their career,

workers in these occupations are unlikely to fall within the very low, low or moderate

household income bands, particularly where they reside with another income earner. Non-

11

Each of the other 5 household types use their corresponding distributions

City of Melbourne Housing Needs Analysis

35

tertiary educated key workers – such as child carers, hospitality workers, cleaners, delivery

drivers and chefs – are more likely to have lower incomes and experience housing stress.

It is therefore difficult to identify Key Workers based on observable characteristics (e.g.

occupation). It could be argued that all workers are ‘key’ in some aspect, whether it be to the

wellbeing of their firm, industry, or local economy/community where they are employed.

Therefore, the objective of this fourth scenario can be viewed as solving a two-step problem:

▪ Of the households in need of housing assistance, which include Key Workers and how

can they be identified?

▪ In what locations across metropolitan Melbourne, is social and affordable housing

required to cater for the needs of these Key Worker households?

While individuals across all three income groups (very low, low, and moderate) may be

engaged in the workforce from time to time, it is likely that those in the ‘Moderate income’

category derive most of their earnings from employment, and are the individuals implied by

the term Key Worker. Those in the lower income categories are more likely to depend on

other sources of income (e.g. government assistance, pension, superannuation) and therefore

are less likely to work full time. In Greater Melbourne (GCCSA), 68 per cent of individuals

(aged over 20 and not studying) earning a moderate income were employed full time,

compared to only 33 per cent for those earning a low income and just 4 per cent for those

earning a very low income (ABS Census 2016). Therefore, in the following analysis it has been

assumed that all moderate income households contain Key Workers.

For context, Appendix 3 provides additional analysis of the income characteristics of Key

Workers, using a selected group of occupations. This illustrates the dispersed income

distributions for occupations which are often referred to as Key Worker, with some

(particularly essential services such as teachers/emergency services) primarily earning above

moderate incomes. Note that the analysis is conducted for lone persons, as the income

characteristics of other household types are difficult to determine (e.g. a moderate income

couple family household may have one member earning an above moderate income while

the other earns a very low income).

This scenario applies the same assumptions as Scenario 3 for those in-need households in the

Very Low and Low income categories but adopts an employment-weighted distribution for in-

need households in the Moderate income category. As a result, those locations which host a

large shares of moderate income jobs have been assigned a higher share of the total social

and affordable housing demand which stems from moderate income households. This

allocation of demand from moderate income households has been derived via the following

process:

▪ Establish the existing relationship between income groups and industry classifications

(1-digit ANZSIC 2006), shown below in Figure 26

▪ Apply this distribution to SGS’s employment by industry forecasts, which will reflect