What Works:

A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America

and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

November 2013

J. Robert Hunter | Director of Insurance

Tom Feltner | Director of Financial Services

Douglas Heller | Consulting Insurance Expert

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

Table of Contents

Executive Summary……………………….………………………………………….…page 1

Part 1. Analysis of Auto Insurance Rates from Every State.……………………...page 4

Overview…..……………..………….…………………………………………...page 4

Analysis…..…………….…………………………...……………………………page 4

Findings…..…………….………………………...……………………….……..page 14

Part 2. In Focus: California's Regulatory Success Story..…………….…………...page 17

Overview….…………….………………………...…………………..….…….. page 17

Background on Prop 103…..…………………...……………………………...page 18

Measuring Success in California……………….…………………………..…page 19

Regulatory Standards of Excellence…….…….………………………….…..page 32

Challenges and Innovations …..……..............……………………………....page 43

Part 3. Recommendations and Conclusion...…….………….……….….………. …page 49

Appendices….………….………….………….………….………….………….….…..page 53

A. Appendices 1-A through 1-I…..….………….…..……….………….…..….page 53

B. Appendix 2 - Text of Prop 103……………………………………………...page 64

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Michael Best, Michelle Styczynski and the staff of

Consumer Federation of America for their advice and assistance in assembling the

analysis and findings contained in this report.

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 1

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

Executive Summary

Over the past quarter century, auto insurance expenditures in America have risen by more

than 40 percent. Consumers in some states are paying 80 percent, 90 percent, and even

100 percent more for auto insurance than they paid in 1989. These increases have accrued

despite substantial gains in automobile safety and the arrival of several new players in the

insurance markets. Only in California, where a 1988 ballot initiative transformed oversight

of the industry and curtailed some of its most anti-consumer practices, has the amount that

drivers spend on auto insurance declined.

This report follows prior reports in 2008 and 2001; it is part of Consumer Federation of

America’s ongoing effort to evaluate the various types of insurance regulatory regimes

found across the country and identify best practices from a consumer protection

perspective. The data sets we have reviewed allow us to conduct a rigorous comparative

analysis of both state markets and regulatory systems.

The data provides several important findings about the insurance marketplaces in each

state and the efficacy of different approaches to insurance regulation. We found,

On insurance prices:

1. The average expenditure on auto insurance since 1989 has increased by 43.3 percent;

2. The states with the highest increases are Nebraska, Louisiana, Montana, Wyoming and

Kentucky;

3. The states with the lowest increases are Hawaii, New Hampshire, New Jersey,

Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania; and

4. Only California has seen average expenditures decrease since 1989.

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 2

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

On regulatory systems:

1. The prior approval system of regulation, in which insurers must apply for rate changes

before they can be imposed in the market, is most effective at keeping rates low;

2. Markets that are less or not regulated tend to have the most substantial increases;

3. While mildly and strongly regulated states tend to have very or somewhat competitive

markets for auto insurance, deregulated and flexible rating states have the least

competitive markets; and

4. Insurance companies are generally able to adapt to any regulatory system and

consistently maintain reasonable profitability.

On California's unique success:

1. Over $100 billion in savings for motorists as a result of lower auto insurance rates

driven by the strong regulatory oversight and more competitive market fostered by the

1988 insurance reform measure known as Proposition 103;

2. Between 1989 and 2002, insurance companies operating in California issued over $1.43

billion in premium refunds to more than seven million policyholders under Proposition

103’s rollback mandate;

3. State rules prohibit many of the discriminatory elements that plague low-income and

minority consumers in other states, especially prohibitions on use of credit scoring and

prior insurance coverage as rating factors;

4. State rules temper the impact on consumers of other non-driving related classifications,

such as territory and occupation by requiring that the most weight in the pricing for a

consumer be given to driving record;

5. The intervenor system, allowing systemically-funded public challenges to rate hikes,

improves both industry and government accountability; and

6. The state has innovated in the marketplace with the implementation of an unsubsidized

alternative policy for low-income consumers.

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 3

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

The research conducted for this paper, building on prior research, clearly indicates that

consumers across the country would be better served with a more robust, prior-approval

system of auto insurance regulation than the system currently in place in most states.

Policymakers and regulators should consider these findings as they look for ways to better

protect consumers from marketplace abuses and from unnecessary increases in insurance

premiums.

If every state in the nation were to implement and enforce a regulatory agenda as

demonstrably pro-consumer as that in California, the research indicates that Americans

could save over $350 billion over the next decade, even as insurance companies realize

reasonable profitability. In order to achieve the most effective form of a prior approval

system, states should construct an intervenor system that provides resources for citizen

and organizational watchdogs who can serve as both a resource for and check on state

Departments of Insurance and who will help hold insurance rates down to appropriate

levels. Further, states should proscribe the egregious non-driving related premium factors

that lead to higher premiums for low- and moderate-income drivers.

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 4

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

Analysis of Auto Insurance Results

from Every State

A. Overview

A primary purpose of this report is to assess the effectiveness of the various regulatory

approaches to auto insurance across the country. Through our research we have identified

the best practices that can serve as models for regulators and policymakers seeking to

ensure a competitive and fair market that is first and foremost protective of consumers. In

order to develop our findings we have looked at data from 1989-2010 (the last year for

which complete data are available, except where noted)

i

and considered a variety of

questions about state markets and the regulatory systems in each state. Among those

questions are:

1. How have auto insurance expenditures changed over time?

2. How have expenditure changes differed under different regulatory systems?

3. How competitive is the auto insurance market in each state?

4. How profitable has the industry been in each state?

5. What factors other than the regulatory approach might explain state variation in

expenditure change over time?

6. What steps have states taken to ensure fair rates and how successful have they been?

B. Analysis

Annually, Americans spend $174 billion on auto insurance.

ii

Between 1989 and 2010 auto

insurance expenditures across the country increased by 43 percent. However, the amount

spent on auto insurance and the change of insurance costs over time varies dramatically

from state to state. In fact, the national average increase of 43 percent was significantly

influenced and lowered by data from the nation's most populous state, California, which is

also the only state to have experienced a reduction in the average spent on auto insurance

annually. The median increase during this time period was Wisconsin's 56 percent rise in

I.

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 5

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

insurance costs, while Nebraskans’ spending on auto insurance doubled over the twenty

one year period.

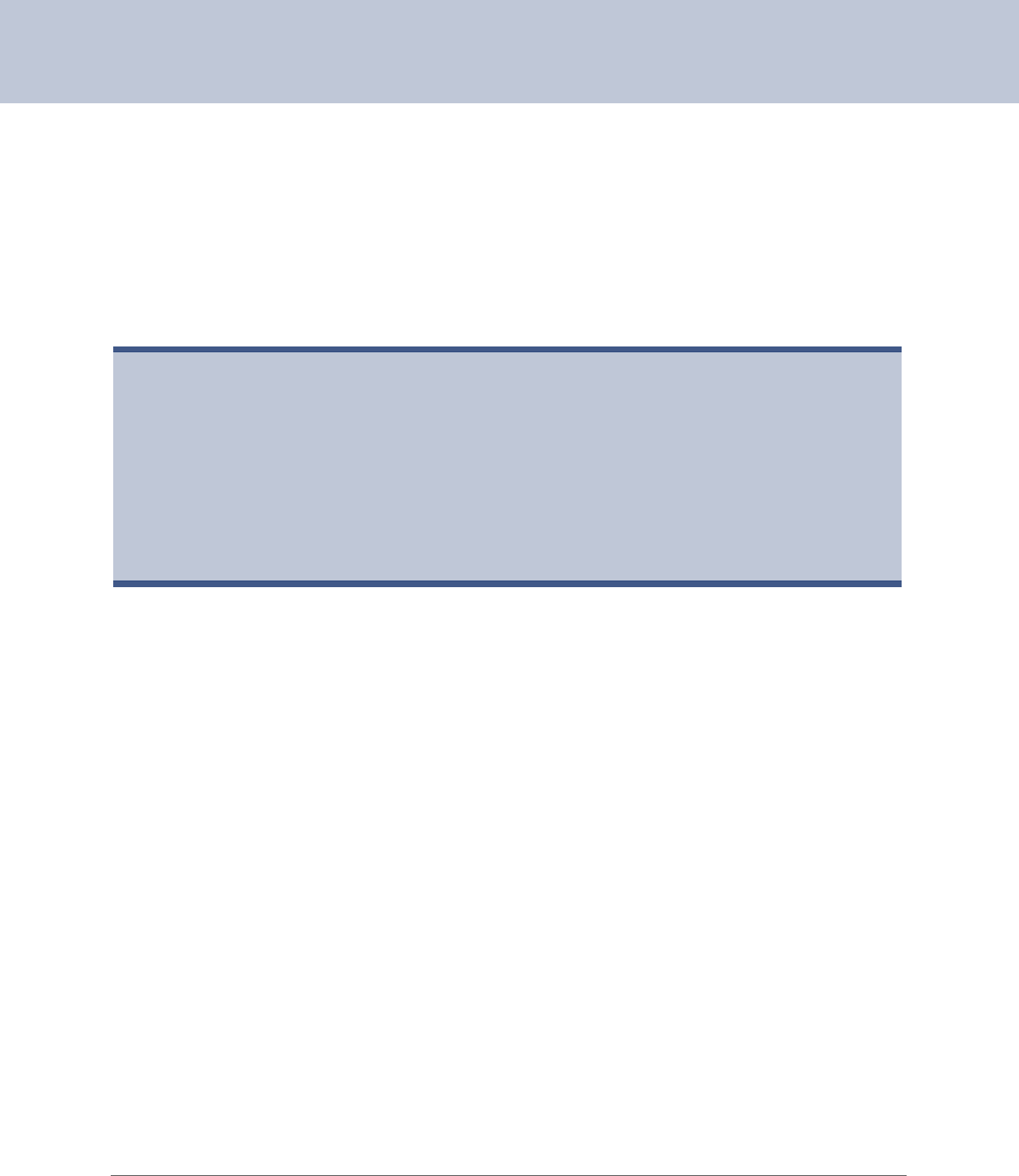

Figure 1. Best to Worst: Change in Auto Insurance Expenditures 1989-2010

As Figure 2 shows, during this two-decade period expenditures on auto insurance have

increased by more than 50 percent for drivers in 32 states. Thirty-eight states and the

District of Columbia have faced increases above the national average of 43.3 percent. See

Appendix 1-A. (An alternative calculation of auto insurance cost changes - the change in

average premium - shows similar changes, with a national increase in average premiums of

42.8 percent.)

iii

-0.3%

43.3%

56.3%

108.1%

California

National Average

Wisconsin

Nebraska

Best

Average

Worst Median

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 6

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

Figure 2. Change in Average Expenditure on Auto Insurance 1989-2010

108.1%

96.1%

95.4%

95.1%

92.3%

92.0%

89.9%

86.8%

86.1%

83.5%

81.6%

79.6%

75.4%

73.5%

70.5%

69.9%

69.7%

69.0%

66.2%

62.2%

58.9%

58.7%

58.6%

57.7%

57.3%

56.3%

55.4%

54.6%

53.8%

52.8%

51.5%

50.5%

49.3%

48.8%

46.7%

46.6%

45.0%

43.3%

42.3%

41.7%

41.1%

38.4%

38.3%

35.7%

33.9%

30.4%

25.7%

22.3%

17.7%

15.9%

13.7%

-0.3%

Nebraska

Louisiana

Montana

Wyoming

Kentucky

South Dakota

West Virginia

North Dakota

Utah

Kansas

Arkansas

Delaware

Oklahoma

Iowa

Texas

Florida

Michigan

Mississippi

Washington

New York

Alaska

Nevada

New Mexico

Missouri

Idaho

Wisconsin

Oregon

North Carolina

Virginia

Alabama

Tennessee

Minnesota

South Carolina

Vermont

Maryland

Indiana

Illinois

National Average

Dist. Of Columbia

Colorado

Georgia

Ohio

Arizona

Rhode Island

Maine

Connecticut

Pennsylvania

Massachusetts

New Jersey

New Hampshire

Hawaii

California

-0.3

Decline in average expenditure

(California only)

Below national average

National average

Above national average

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 7

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

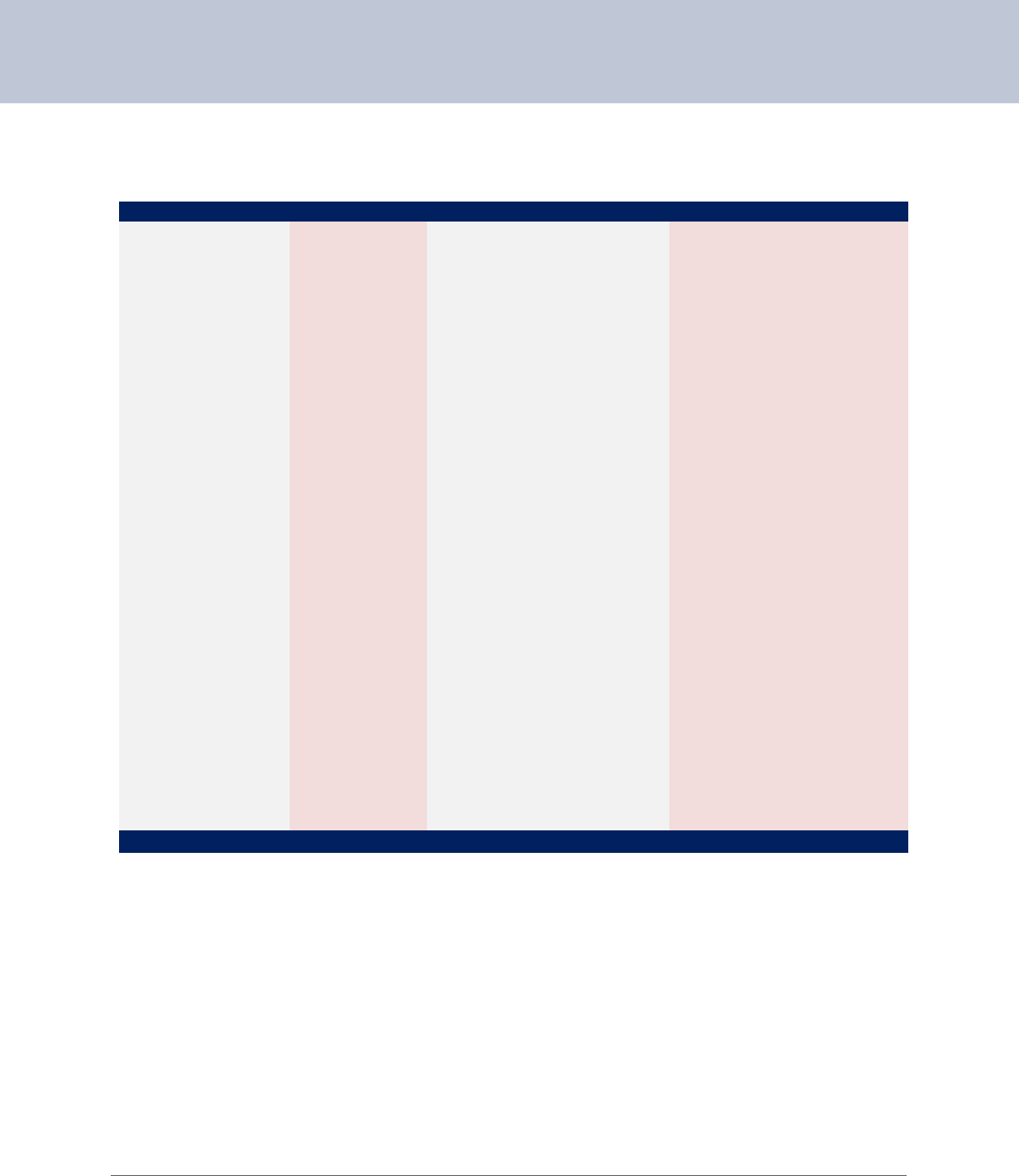

Differences by Regulatory System

In the United States, auto insurance is regulated at the state level. Each state has its own

unique set of laws and no two states' insurance regulation regimes are precisely the same.

However, the states can be grouped, generally, among five different regulatory structures,

ranging from the vigorous "prior approval" approach to rates in California to the virtual

deregulation of rates in Wyoming. The five structures are:

Our findings show that states with stronger regulatory systems - that is, states that require

prior approval of rates before they can take effect - have had the most success in keeping

auto insurance costs down. Figure 4 shows the regulatory system of the five states with the

lowest auto insurance expenditure changes and the five states with the largest increases.

Prior Approval

Regulator

approves rate

change prior

to use

File & Use

Rate must be

filed before

use, no

approval

Use & File

Rates are filed

after they are

used in

market

Deregulated

No state

review of

rates, no filing

requirement

Figure 3. Regulatory System by State

DC

AK

HI

Source:

Flex

Rates can be

used without

notice within a

certain range

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 8

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

Figure 4. Regulatory Systems of States with Lowest and Highest Rate Changes

Lowest Rate Changes

Highest Rate Changes

State

Regulatory

Structure

Change

State

Regulatory

Structure

Change

California

Prior Approval

-0.3%

Kentucky

Flex

92.3%

Hawaii

Prior Approval

13.7

Wyoming

Deregulated

95.1

New Hampshire

File & Use

15.9

Montana

File & Use

95.4

New Jersey

Prior Approval

17.7

Louisiana

File & Use

96.1

Massachusetts

File & Use*

22.3

Nebraska

File & Use

108.1

*Until 2008, MA used a state set system of ratemaking, which is an even stronger regulatory structure than prior

approval. Since 2008, it has operated under a file and use system.

A simple average of the rate changes for the states aggregated by regulatory system

illustrates the benefit to consumers of stronger regulatory regimes. Drivers in Prior

Approval states have endured the lowest rate hikes, while those in Flex Rating and

Deregulated states have seen the largest increases. (A premium-weighted analysis of the

changes by regulatory systems keeps the same order as the simple averaging, except that

the Deregulated states weighted increase is lower than all but Prior Approval, as a result of

the dramatic population difference between the two states, Illinois and Wyoming.) See

Appendix 1-B.

Figure 5. Average Increase in Auto Insurance Expenditures by Regulatory System 1989-2010

48.0%

60.4%

61.7%

66.8%

70.1%

Prior Approval

File & Use

Use & File

Flex

Deregulated

(Strongest)

>>

>>

>>

(Weakest)

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 9

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

Competition in the Auto Insurance Marketplace

Unlike most products and services sold in the American marketplace,

auto insurance is a government-mandated purchase for motorists in

all states, save New Hampshire.

Additionally, the insurance industry has a rare exemption from

federal antitrust laws and state antitrust laws in many states.

Finally, insurance is a complex financial instrument that, for most

people, is purchased but rarely, if ever, used, and studies show that

consumers do not shop for coverage frequently.

iv

The interaction of

these unique qualities makes the role and relevance of a competitive

marketplace a complicated concern.

We consider two indicators of competitiveness, a standard measure

and an analysis of state policy regarding market participation.

A Formal Measure of Competitiveness

To identify the level of market competition in the

auto insurance market, we used the test

commonly employed by the United States

Department of Justice (DOJ) to measure

competitiveness in a market, the Herfindahl-

Hirshman Index (HHI).

v

The closer a market is to

being a monopoly, the higher the HHI index. The

DOJ considers a market with a score of less than

1,000 to be a competitive marketplace, a score of

1,000-1,800 to be a moderately concentrated

marketplace and 1,800 or greater to indicate a

highly concentrated marketplace.

State HHI

Maine 633

Vermont 662

Connecticut 702

New Hampshire 714

California 753

Washington 762

North Dakota 763

South Dakota 784

Nevada 788

Utah 796

Figure 6. Most Competitive Markets

See Appendix 1-C for all states’ HHI scores

“Regulatory

systems that

allow the most

unregulated

market

activity

produce the

least

competitive

markets.”

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 10

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

Our analysis finds that, generally, the level of competition tends to decrease, and HHI score

increase, as regulation of the market gets weaker, except that the weakly regulated Use and

File states have the lowest average HHI score. Half of the ten most competitive states use a

Prior Approval system of regulation. Most notable, however, is that the regulatory systems

that allow the most unregulated market activity – Flex Rating and Deregulated states –

produce the least competitive markets. Deregulated states have average HHI scores of

1,207 and Flex states have an average HHI of 1,311, far higher than the averages of U&F, PA

and F&U at 865, 996, 1,031, respectively (See Figure 7).

Figure 7. Average HHI by State Regulatory System

996

1,031

865

1,311

1,207

Prior Approval

File & Use

Use & File

Flex

Deregulated

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 11

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

Competition-Enhancing Policies

Given the unique market power held by insurance companies vis à vis consumers, who have

to purchase their product, states can play an important role in ensuring that motorists can

access a competitive market for auto insurance. Below we describe several competition

enhancing rules and practices we found amongst the states:

1. Take All Good Drivers. Only four states, California, Massachusetts, New Hampshire

and North Carolina require insurers to take all good drivers who apply for insurance. In

these states, a good driving record gives a consumer the right to obtain insurance from

any licensed insurance company. This is a pro-competitive requirement, since all states

but one require that consumers purchase auto insurance as a condition of driving their

own car. Because of these mandatory insurance laws, auto insurance demand is

inelastic. A mandate on insurers requiring that coverage be made available to good

drivers balances this supply-demand situation.

2. Enact and Enforce Antitrust Laws. Only one state, California, fully applies its antitrust

laws to the insurance industry. The insurance industry has historically engaged in

extensive price fixing, relying in many instances on shared pricing tools developed by

an industry funded “rating organization.” When the industry is subjected to antitrust

laws companies cannot engage in this collusive data sharing, which tends to result in

inflated prices.

3. Prohibit Shifting Good Drivers to Non-Preferred, Higher Rate Subsidiaries.

California is also the only state to require that an insurer group place good drivers into

the lowest priced policy available from any of its companies when an insurance

applicant asks for a quote. This blocks insurance companies from shifting drivers with

good records into the expensive insurance policies written by an insurer’s non-

preferred subsidiary, which has been one of several techniques that insurers use to

avoid selling policies to good drivers who do not fit into a company’s target

demographic.

4. Insurer Profitability under Different Regulatory Systems. We considered the

question of whether the regulatory system in a state tends to support more or less

profitability for the industry. Presumably, insurers would prefer a system that supports

higher profits. As Figure 8 indicates, however, profits are relatively unaffected by

regulatory systems, with only a slight trend toward higher profits in states with less

regulation on an unweighted state-by-state basis, except that Flex Rating systems seem

to trend toward lower profitability.

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 12

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

Figure 8. Profitability by Regulatory System, Weighted by Market Size

Regulatory System

Total Premium

(in billions)

Average Annual

Profitability

Prior Approval

$63.4

9.4%

File & Use

$63.8

7.7%

Use & File

$12.6

9.7%

Flex

$4.7

4.5%

Deregulated

$5.1

9.7%

Total

$150

8.6%

Perhaps most notable is the clear evidence that the stronger regulatory oversight

associated with Prior Approval systems does not inhibit insurer profitability as some

opponents of regulation might suggest. Figure 9 illustrates the five most profitable states

since 1989 and the five least profitable states. Although there is a tendency toward higher

profits in the less regulated states, the full list of states reveals that those with prior

approval systems are distributed throughout the profitability range, with Hawaii as the

most profitable, Nevada tied for the least, and another prior approval state, North Dakota,

marking the data set’s median at 9.1% average annual profit since 1989. See Appendix 1-D.

Figure 9. Most and Least Profitable States (Average Annual Profitability) 1989-2010

Most Profitable

Least Profitable

State

Regulatory

Structure

Profitability

State

Regulatory

Structure

Profitability

Hawaii

Prior Approval

17.4%

Kentucky

Flex

4.7%

Maine

File & Use

14.0%

Michigan

File & Use

4.4%

Dist. Of Columbia

File & Use

13.7%

Louisiana

File & Use

3.9%

New Hampshire

File & Use

13.4%

Nevada

Prior Approval

3.7%

Vermont

Use & File

12.9%

South Carolina

Flex

3.7%

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 13

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

Steps States Have Taken to Ensure Fair Rates

Auto insurance prices can vary tremendously, based on the factors used by insurers to

determine these rates. Some rating factors, like driving record, make a lot of sense in that

the classification is based on a logical predicate: people who have driven poorly in the

recent past will continue to drive poorly in the future and, hence, are more likely to file a

claim. Moreover, data analysis confirms that this hypothesis is correct. Other rating

factors, like credit scoring, do not have a logical or legitimate thesis underlying their use

and are only supported by data that purports to show a correlation, but not a causal or

even logical connection to a policyholder’s driving record.

Our review shows that several states have taken steps to control or prohibit the use of

unfair procedures to develop rate classifications like credit scoring. For example, Maryland

has banned the use credit scoring for home insurance, but not for auto insurance. Hawaii

and California have banned its use for auto insurance. Other states have put some

restrictions, usually modest ones, on the use of credit scoring for underwriting and pricing

insurance.

Only California has a comprehensive system to ensure that rates are set fairly. In that state,

three auto rating factors are mandatory and must have the greatest impact on automobile

insurance rates, with the first factor having the greatest impact of the three, and the third

factor the least impact. The three factors are: (1) driving record, (2) miles driven, and (3)

years of driving experience. Insurers can also propose other factors for approval. Credit

scoring has not been approved for use in California. If another factor is approved (and

several have been, ranging from type of vehicle driven to marital status and ZIP code of a

driver’s residence) that factor must have less impact on insurance rates than the third

mandatory factor. Thus, unfair factors, even if they are approved, will have a limited

impact on an individual’s final auto insurance price. For example, the impact of territory –

where a consumer lives – has been substantially reduced under California’s rules.

In reviewing the regulatory systems of the states, we found that the most comprehensive

regulatory requirements, with express standards for evaluating insurer rates and expenses,

were the regulations of California. California is also the only state that funds consumer

participation in the rate-setting process if an intervening consumer or consumer group

makes a “substantial contribution” to a rate hearing. Three other states (Florida, South

Carolina and Texas) had consumer advocates with the authority to intervene in a rate

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 14

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

hearing on behalf of consumers. In Massachusetts, the attorney general can intervene in

the ratemaking process.

C. Findings

Stronger Regulation Leads to Lower Rates for Automobile Insurance

Consumers

We evaluated three significant factors in each state and for each of the five regulatory

systems in use across the nation.

The first test examined the ability of a rating system to hold down rate increases. It was

very clear in the results that the more stringent the regulatory regime, the lower the price

increases that were observed. Prior Approval prices rose the least, rates in File and Use

states the next slowest and then Use and File states. States with the least regulation,

Flexible Rating and Deregulated states, were the least successful at holding prices down

over the long term.

The second test was a test of competitiveness. Use and File states reported the least

market concentration and highest average competitiveness, though half of the ten most

competitive states were Prior Approval states (Prior Approval is only used in one-third of

the states). States with Prior Approval and File and Use averaged around the 1,000 HHI

breaking point, right between markets that are deemed to be competitive and those that

are moderately concentrated. Most notably, deregulated systems, often called “Competitive

States,” exhibit the most market concentration and least competitive markets.

Next we examined the profits of the insurers in each state, categorized by regulatory

system. It is not good for consumers if insurer profits are either too high or too low.

Consistently low profits could lead to bankruptcy and volatility in the market, which is very

disruptive to policyholders. Extremely high profits usually mean that insurers are charging

too much for coverage. We found that profits do rise somewhat as regulation weakens,

which is to be expected, although Flexible Rating states, which are weakly regulated, had

substantially lower profit margins than any other system. Over the long term, profits in

states with Prior Approval regimes are just under those in states that employ a File and Use

system, and a point less than profits in states that have a Use and File process or a

Deregulated regime. It is evident that in all cases and under any regulatory system,

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 15

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

insurers have managed to thrive over the decades, enjoying reasonable profitability in

virtually every state.

Overall, the Prior Approval system of regulation works best for consumers. This system is

superior at holding prices down, yet allowing reasonable insurer profit and maintaining a

competitive market. It is also clear that the worst regulatory regime for consumers is the

Deregulated, so-called “competitive” system, which does not hold down prices, allows

somewhat higher profits than other regimes and results in less competitive markets.

We also analyzed data on several other key factors that could affect insurance rates,

including seatbelt laws, bad faith claims settlement laws, uninsured motorist population,

size of the residual market, the legal regime in use for auto claims, thefts per 1,000 vehicles,

traffic density, disposable income, repair costs and other factors, as shown in the

appendices. These data do not appear to be confounding variables and instead help us

affirm the first general finding that Prior Approval regulation is the best system for

consumers. The data further sheds light on the second significant finding of this analysis,

that California’s active prior approval system exceeds even its prior approval peers in other

states in ensuring access to reasonably priced auto insurance rates.

California Stands Out From All Other States in Having the Best Regulatory

System for Protecting Consumers

In our review of the findings cited above, we found that one state – California –passed

virtually every test for good performance, with the exception of a high-uninsured motorist

population and profit levels for insurers that are higher than necessary. We found the

following results for California:

Ranked first among all states in holding down rate increases;

Ranked fifth in market competitiveness as measured by the HHI;

The only state to totally repeal its antitrust exemption for automobile insurers;

Has a low residual market population (i.e., low level of participation in higher cost

assigned risk plans);

Among the eleven states with the highest ranking from the Insurance Institute for

Highway Safety for strong seat belt laws;

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 16

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

One of only four states to guarantee insurance to a good driver from any insurer the

driver chooses;

The only state to require that a person’s driving record be the most important factor in

determining insurance rates;

One of only three states to ban the use of credit scoring;

The only state that funds consumer participation in the ratemaking process if they

make a substantial contribution; and

The only state that bars insurance companies from considering whether a motorist was

previously insured, or had a gap in coverage (such as a short drop of insurance during a

time with no car) when pricing applicants for auto insurance.

On the negative side, California has the seventeenth highest uninsured motorist population

in the nation according to the industry organization, the Insurance Research Council (IRC).

While still too high, the population has decreased sharply from the 1980s when California

had one of the highest rates of uninsured motorists. California has an uninsured motorist

rate of 15 percent, according to the IRC study, compared to a 14 percent rate nationally.

vi

California’s unique situation as home to more undocumented (and, thus, unlicensed

drivers) in the nation may explain some of the uninsured population. That is likely to

change in coming years in the wake of a new state law allowing undocumented immigrants

to obtain drivers licenses and thereby purchase insurance more easily. Profits for auto

insurers over the last 20 years have also been too high in California, 12.1 percent in the

state compared with an 8.5 percent annual average nationally, indicating that regulators

should require insurance companies to further reduce their rates.

On balance, California is clearly the best state in the nation for consumers buying auto

insurance. We therefore studied the California system in-depth.

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 17

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

In Focus: California’s Regulatory

Success Story

A. Overview

The balance of this report is focused on the successes and failures of California’s regulatory

system, so that the public and policymakers can understand the details of the system that

works better than any other in the nation to protect consumers. In this section we review

the history of California’s uniquely strong consumer protection standards and detail the

specific policies in place that have contributed to the state’s success in fostering the fairest

auto insurance system in the country.

Additionally, we provide more detailed findings related to California from the research

conducted for Part I of this report. In summary, we found that California:

Was the only state in the nation to experience decreased auto insurance expenditures

between 1989 and 2010;

Maintained a highly competitive market for auto insurance, with the fifth lowest market

concentration score in the nation and was the most competitive state outside of the

New England states (which have historic reasons for being particularly competitive);

Has very few drivers who turn to the high cost coverage of last resort known as the

residual market;

Has the only system of classifying risks that requires that a driving record have the

most impact on a driver’s premium and that eliminates or limits the impact of

questionable non-driving-related classes like credit score;

Encourages consumer participation in the regulatory process and provides regulators

and consumers with a series of tools to ensure fair practices in the marketplace; and

Has the nation’s only low cost program for low-income good drivers.

II.

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 18

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

B. Background on Proposition 103

Twenty-five years ago, on November 8, 1988, the people of California adopted an insurance

reform initiative, Proposition 103 (attached, Appendix 2), by a narrow 51 to 49 percent

margin. This was a remarkable victory for consumers, especially considering that the

insurance industry spent $63.8 million opposing reform, while the grassroots campaign for

Proposition 103, led by consumer advocates, spent only $2.9 million, less than 5 percent as

much.

Proposition 103 replaced a regulatory structure that placed virtually no restrictions on

how insurers determined rates or what they charged—similar to the system in use in

deregulated states today. Despite nearly 100 lawsuits brought by insurance companies to

invalidate Proposition 103 and numerous attempts to weaken or repeal the law by

legislation and initiative, the measure remains in force twenty five years after enactment

and continues to be the nation’s most effective insurance reform law.

Through Proposition 103, voters made several changes to California law, giving the state

the nation’s most robust insurance regulatory system, one of the most competitive markets

in the country and creating the nation’s most transparent and accountable marketplace and

regulatory environment. Its key provisions are listed below. See Appendix 2 for the text of

the law.

Regulating Rates, Premiums and Underwriting Practices

Proposition 103:

Imposed a 20 percent rate rollback on most property and casualty insurance

companies doing business in California that returned $1.43 billion to customers;

Adopted a Prior Approval system that required insurance companies to justify any rate

change to the Insurance Commissioner before it can take effect.

Requires insurance companies to sell auto insurance to any good driver who requested

it;

Requires insurers to give all good drivers an automatic 20 percent “good driver

discount;”

Requires insurers to base auto insurance premiums primarily on driving safety record,

miles driven and years of driving experience; and

Prohibits companies from surcharging customers who did not have prior insurance

coverage.

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 19

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

Encouraging Competition in the Marketplace

Proposition 103:

Repealed the insurance industry’s state anti-trust exemption;

Repealed the state’s anti-rebate law;

Applies the state’s unfair business practices and unfair competition laws to the

insurance industry;

Applies the state’s civil rights laws to the insurance industry;

Allows consumers to negotiate group insurance rates; and

Requires the Department of Insurance to create an insurance rate comparison system

available to the public.

Increasing Transparency and Accountability for the Industry

and its Regulator

Proposition 103:

Makes public all information submitted by insurance companies as part of the prior

approval process;

Allows consumers and other members of the public to intervene in order to challenge

rates or other proposed changes by insurance companies and requires insurers to fund

the cost of these challenges if the intervenor makes a substantial contribution to

reaching the decision;

Gives consumers the right to challenge insurance companies’ practices and

Commissioner decisions in Court; and

Made the Insurance Commissioner an elected rather than an appointed position.

C. Measuring Success in California

In reviewing the national data concerning the impact of regulatory systems and other

factors on auto insurance rates and premiums, the clearest conclusion that can be drawn

from the data is that California is far ahead of the rest of the nation in terms of limiting

excessive rates and protecting consumers from abusive pricing practices. By virtue of a

number of key data points, the California experience is unique. What follows is a

discussion of several of the factors that convince us that California’s Proposition 103,

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 20

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

notwithstanding certain problems in its enforcement, provides a template for high quality

consumer protection and effective insurance industry reform.

More than $100 Billion Saved by California Drivers 25 Years after Prop 103

– a $4.29 Billion per Year Dividend

In 2010, the average American driver spent 43.3 percent, or $239, more on auto insurance

than he or she would have in 1989. In fact, drivers in every state but one spent more on

average on auto insurance in 2010 than in 1989. The one state that defied the national

trend was California, which, on November 8, 1988, enacted a transformative reform

measure – Proposition 103 – that set California on this path to savings.

Figure 10 presents several different measures of performance with regard to the cost of

auto insurance in California and countrywide. By each measure, California outpaces the

nation in terms of consumer savings. With the exception of average annual collision

premiums, California’s cost ranking relative to other states has fallen significantly for

consumers. Regarding the average premium charged for liability coverage – the only

required auto insurance coverage – California fell from being the 2

nd

most expensive state

in the nation in 1989 to the 30

th

most expensive in 2010. For comprehensive coverage,

California fell from 9

th

to 48

th

. All told, California has enjoyed the lowest rate of increase of

any state in the nation since the adoption of Proposition 103. See Appendix 1-E for the

complete data set.

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 21

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

Figure 10. Measures of Average Auto Insurance Expenditure and Premium

In 2010, Californians were spending 0.3 percent less on auto insurance than they spent in

1989, even as the nation spent 43.3 percent more on average. Hawaiians, who saw a 13.7

percent expenditure increase over the period, saw the results closest to California and only

four states saw increases less than 25 percent, while drivers in 32 states endured increases

of more than 50 percent. After adjusting for inflation, Californians were spending 43

percent less on average on auto insurance more than two decades after the passage of

Proposition 103 than when insurance was sold in an unregulated market.

Prior to the passage of Proposition 103, auto insurance prices in California rose faster than

the national average. Since then, California premiums have crept slightly downward

annually while the national average has increased 1.8 percent a year. Using a savings test

-16.90%

35.20%

43.60%

47.10%

-14.3%

42.4%

0.9%

42.8%

-0.3%

43.3%

Percent Change in Average Premiums

Percent Change in Liability Premiums

Percent Change in Collision Premiums

Percent Change in Comprehensive Premiums

Countrywide

California

Countrywide

California

Countrywide

California

Countrywide

California

Percent Change in Average Expenditures

Countrywide

California

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 22

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

analysis that assumes that, in the absence of Proposition 103, California auto insurance

rates would have merely kept pace with the national rate of change, the actual savings

realized by California auto insurance customers was $90 billion through 2010, the latest

year for which data are available.

Assuming that the same rates of change have persisted in California and the nation since

2010, we can project that in the quarter century since Proposition 103 began to reform the

insurance industry, Californians have saved $102.87 billion, rounded quite coincidentally

to $103 billion. It should also be noted that an additional $1.43 billion was refunded

directly to consumers under Proposition 103’s rate rollback provision. It is unlikely that

any other voter-approved measure in American history returned to customers or saved

consumers as much money as Proposition 103.

Figure 11. Proposition 103 Savings

Other Indicators of Success in California

The sheer scale of the savings achieved under Proposition 103 may seem to diminish

otherwise notable indicators of success that this most-vigorous application of Prior

Approval regulation has brought, but they are worth recounting.

Highly Competitive Market

As noted above, California is the fifth most competitive auto insurance market in America,

and the most competitive outside of New England.

vii

Using the standard HHI market

concentration index, California scores a 753, where anything below 1,000 is considered

competitive. As a contrast, Illinois and its deregulated marketplace earn a market-

concentrated score of 1,216. This was anticipated by the California voters, who identified

“encourag[ing] a competitive marketplace” as one of the chief purposes of shifting from a

deregulated to a well-regulated system. This notion of regulation enhancing competition is

counterintuitive to industry partisans who view regulation as a barrier rather than a

Prop 103

Savings

$4.29 Billion

Each Year

$345 Per Year for

Each Household

in California

$103 Billion

Since 1989

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 23

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

facilitator for market health. In fact, market regulation and transparency have proved to be

very conducive to a competitive marketplace in California, and Californians have dozens of

options to buy insurance from carriers that are actively competing for California business.

Indeed, it is obvious that competition and regulation are not enemies but allies working

together toward the same end: the lowest possible prices delivering fair insurer profits in a

robust market.

Resistant to the Rate Pull of Traffic Density

A common explanation for the variation in auto insurance costs from state to state and

region to region is that accident frequency correlates with traffic density and, therefore,

insurance rates correlate with traffic density. Data comparing state traffic density with

state auto insurance expenditures exhibits a modest density to price correlation, as Figure

12 illustrates.

Figure 12. Average Auto Insurance by Traffic Density

Source (traffic density data): Federal Highway Administration

400

600

800

1,000

1,200

0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5

2010 Average Auto Insurance Expenditure

Millions of Miles Driven Per Mile of Road

California

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 24

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

But California (along with Hawaii) is an outlier, where drivers spend substantially less on

insurance, approximately 23 percent less, than the traffic density-price correlation would

predict. The average annual expenditure would, according to the data, suggest that

California ranks 25

th

in density, with approximately 0.71 million miles traveled per mile of

roadway. In fact, California ranks third in terms of traffic density, with 1.88 million miles

traveled per mile. See Appendix 1-F for the national data.

California’s regulatory system requires that insurers justify rates in the context of costs,

which creates a higher burden for insurers that may want to raise rates on the perceived

relevance of traffic density. California does allow some variation between individual

premiums based on geography, but the regulatory system prevents this presumed risk

factor from having more impact on a consumer’s rate than that consumer’s driving record,

annual mileage driven and years of driving experience. The relatively low rate-to-density

ratio in California, then, is further proof of the success of Proposition 103’s Prior Approval

process.

Little Need for a Residual Market

The residual market for personal auto insurance is the “market of last resort” for motorists

who cannot find coverage in the “voluntary” market where most people buy insurance.

viii

The reason drivers turn to the residual market may be because they have a bad driving

record and no one wants to insure them or, as had been the case in California prior to the

passage of Proposition 103 and many other states, insurers simply refused to offer a policy

to certain good drivers because of other characteristics, such as their ZIP code or their lack

of prior of insurance purchases.

The price for insurance in the residual market is typically

much higher than the premium for voluntary policies.

Insurers have claimed that one way that rate regulation will harm consumers is by

increasing the size of the residual market for personal automobile coverage. They theorize

that regulation keeps rates too low, which discourages insurance companies from offering

coverage to certain kinds of consumers. Following this logic, California’s residual market

should have grown in the wake of Proposition 103’s rigorous rate regulation system.

Simply looking at the size of the residual market does not tell the entire story about the

availability of insurance in the marketplace, as the size of the non-standard and uninsured

markets are needed to fully examine the vitality of the “normal” or “voluntary” market in a

jurisdiction. Still it is worth noting the relationship between California’s strong rate

regulation and the size of the state’s residual market.

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 25

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

According to the industry view, California’s residual market should have expanded to serve

policyholders that insurers stopped serving in response to the regulatory controls enacted

by Proposition 103. Thus, even if rate regulation merely held residual market participation

steady at the 1989 level, where 8.4% of all insured drivers in California were in the

California Automobile Assigned Risk Plan (CAARP), the residual market in the state should

now be supplying approximately two million drivers a year with the insurance that they

could not buy on the open market. In fact, in 2012, there were only 621 cars insured by the

California plan, or less than 0.003% of the market, representing an astounding decline in

enrollment of 99.97 percent.

ix

See Appendix 1-G for the national data through 2010.

California has also created a separate market within CAARP for low-income drivers. The

California Low Cost Auto Insurance program, first established as a pilot program in 1999,

provides approximately 9,000 California drivers annually with reduced-coverage policies

that are priced significantly lower than the voluntary market, to address the needs of the

very lowest income motorists, for whom even strong rate regulation has not pushed the

price of coverage sufficiently low. This is not a residual market since these are good

drivers, entitled to obtain insurance from the insurer of their choice by Proposition 103’s

terms, but because of their income restrictions, they often choose the low-income plan.

Even when noting that the residual markets are now generally smaller in most states than

they were in decades past, it cannot be ignored that California’s rate regulation did not

press drivers into this market, as industry theory holds it should have. There are a few key

reasons related to Proposition 103 for this:

The requirement that insurers sell a policy to any good driver makes discriminatory

sales practices much more difficult than in the past;

The automatic 20 percent good driver discount makes the private market much more

affordable to the vast majority of drivers who have good records; and

The level of competition under California’s regulatory system is so high that companies

are much less willing to ignore pockets of potential customers than they were prior to

the reforms.

California’s effective regulation of rates did not hamper competition and force people into

residual markets for auto insurance. As the market concentration index (HHI) discussed

above demonstrates, and the almost total eradication of a residual market amplifies, the

California market is much more competitive with rate regulation than it was without.

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 26

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

Uninsured Market in California Declining

If rate regulation had the effect of freezing the auto insurance market, as the industry often

claims, another expected result, akin to the predicted increase in residual market

participation, would be an increase in the number of uninsured drivers. Uninsured

motorist data is difficult to agree upon, and the state of California has often used one

method of measuring the uninsured, while the industry-organized Insurance Research

Council (IRC) has used another. At this point in time, however, both sources indicate that

the level of uninsured motorists in California has declined substantially since Proposition

103 took effect.

The IRC, which has more up-to-date data, estimated that in 2009 15 percent of motorists in

California were uninsured. See Appendix 1-H for the national data. That marks a 40

percent decline from the 1989 estimate in which a quarter of all drivers were estimated to

be uninsured. Notably, the IRC methodology for counting the uninsured relies on a model

based on uninsured motorist claims data, which likely includes claims associated with

undocumented immigrant drivers who have not purchased auto insurance because they do

not have a drivers license. California is home to the most undocumented immigrants in the

nation and its estimated uninsured motorist rate is likely skewed upward as a result.

x

In

2013, California lawmakers approved legislation that will give undocumented immigrants

access to driver’s licenses by 2015. We believe this new law will eventually drive the IRC’s

estimate for California’s uninsured motorist rate down further still.

Insurance Industry Profits in California

Insurers often complain that rate regulation improperly suppresses rates and stifles their

profits. However, the data shows that the excellent results for consumers under

Proposition 103 did not come at the expense of insurer profits. Insurers have enjoyed

automobile insurance profits in California that are considerably higher than the national

average during the first two decades of expanded state rate regulation.

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 27

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

Between 1989 and 2011,

California's profit ranked

8th highest in the nation, at

11.9 percent, as compared

with a national average of

8.5 percent. Interestingly,

as the graph shows, much

of this differential was

realized in the decade 1989

to 1998, during the time

that the insurers fought Proposition 103’s rollbacks and while the Insurance Department

was making the regulatory system fully functional. It also includes the first term of

Insurance Commissioner Chuck Quackenbush, an avowed opponent of Proposition 103,

who was elected in 1994 and received an estimated $8 million in campaign contributions

from insurance industry sources. Quackenbush later resigned in 2000 after a scandal

related to his handling of the insurance claims after the Northridge earthquake. Three of

the four highest average rates of return during the two decades occurred under

Quackenbush’s watch.

As the data in Figure 13 (and Figure 14) illustrate, since 1999 California’s average returns

for auto insurers have been much closer, at 8.8 percent, to the national average of 6.8

percent but still higher than the average. Looking only at the past ten years, California has

ranked nearer to the middle of the pack on this measure, yielding the 20

th

highest profits in

the nation.

Figure 14. Rate of Return 1989-2011

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

California ROR

National ROR

Figure 13. Auto Insurer Profits California v. Countrywide

California Countrywide

1989-1998

16.0% 11.0%

1999-2011

8.8% 6.8%

1989-2011

12.1% 8.6%

Personal Auto Insurance

Return on Net Worth

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 28

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

While these data suggest that in California there is still room for further rate reductions,

the profitability also sheds light on the efficiencies that Proposition 103 has generated in

the California market. Subject to the stringent regulation of their rates and exposed to

public scrutiny through the law’s transparency requirements, as well as the attendant

increased competition in the market, insurers in California have done a better job of

streamlining operations than in other states. Further, the fact that California’s system has

allowed insurers to earn profits slightly above average while, uniquely in the nation,

lowering rates for consumers is a testament to the marketplace balance that Proposition

103 has promoted.

Factors other than the Regulatory System that may Affect Rates

For our review we sought to identify other factors that may explain, supplement or

otherwise relate to the changes in rates in California during the two decades we have

analyzed. In addition to the residual market, uninsured motorists and traffic density

discussed above, we assessed seatbelt laws in use, whether states had laws allowing or

prohibiting legal action against insurers including Unfair Trade (or Insurance) Practices

laws and third-party bad faith laws, thefts per thousand people, disposable income per

capita, auto repair costs and the type of legal regime in place for automobile accidents (tort

vs. no-fault). Specifically, we looked to see if there were other unique aspects of the

California marketplace that might be contributing to the state’s unique success. These

state-by-state comparisons are contained in Appendix 1-I.

We have already discussed the fact that while California is an outlier in traffic density –

having the nation’s third busiest roads – its rates are much lower than density predicts.

Similarly, when we considered the percentage of a state’s population in the Metro Area,

each of the ten most urbanized states have expenditures among the 12 highest in the nation

except for California.

California’s per-capita income is above the national average, so that should imply higher

costs due to injury (because of lost wages) and higher value cars. That would explain

higher rates, but again, California’s system overcomes that factor. California’s car theft rate

is above the national average and auto repair costs are slightly below national average,

neither of which exhibit sufficient difference to have any explanatory power.

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 29

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

California is a personal responsibility, or tort state, in which driver’s are responsible for the

accidents they cause, as opposed to a no-fault state. This makes California similar to most

states (31 states are tort based and the 6 “add-on” states are essentially tort, too).

California has primary seat belt enforcement, again typical of most states, and it follows the

most common top speed limit of 70mph. Each of these items would be expected to result in

California experiencing expenditure changes similar to other states, rather than the

decrease in auto insurance rates since 1989 that is unique to California.

Another factor we have considered is a change in the interpretation of California’s “bad-

faith” law. The insurance industry and its partisans assert that, rather than Proposition

103 and its strong regulatory oversight of the insurance industry, a 1988 California

Supreme Court ruling,

Moradi-Shalal v. Fireman’s Fund Insurance Cos.,

xi

is responsible for

the dramatic post-Proposition 103 premium rate savings. Moradi-Shalal barred the victims

of negligence by an insured driver from bringing lawsuits against the driver’s insurance

company for refusing to pay claims promptly and fully. The insurers say that by barring

such “third party” lawsuits the court decision reduced liability claims and payouts, and thus

led to lower rates.

This argument is contradicted by several aspects of the data reviewed for this report. First,

since the passage of Proposition 103, premiums for comprehensive coverage (which covers

theft or damage to a vehicle not caused by a collision) have declined markedly relative to

the national trend. This cannot be explained by Moradi-Shalal’s prohibition of so-called

third-party bad faith lawsuits as comprehensive coverage is a first party coverage subject

to the full accountability of the California civil justice system. If California’s success in auto

insurance premium control had been the result of limits on third party bad faith lawsuits,

comprehensive premiums would be entirely untouched by this fact and would be expected

to exhibit premium changes similar to the national experience. In fact, the difference

between California and the countrywide average change since the passage of Prop 103 is

more than 52 percentage points, with comprehensive premiums increasing by 35 percent

nationally while declining by nearly 17 percent in California. As shown in Figure 15,

California comprehensive insurance premiums that were 23 percent higher than the

national average in 1989 are now 25 percent lower than average.

Collision premiums, also a first party coverage, increased less in California (43.6 percent)

than nationally (47.1 percent), and liability premiums, which cover third party claims,

decreased by 14.3 percent in California and increased by 42.4 percent nationally.

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 30

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

Figure 15. Comprehensive Premium, California v. Countrywide

These data imply that the primary cause of the rate savings are due to Proposition 103 and

not consumers’ access to the courts.

Additionally, research comparing California with other states also contradicts the

industry’s argument that the limited change to California’s “bad-faith” law was responsible

for the dramatic premium savings after Proposition 103. Most states prohibit lawsuits in a

manner similar to Moradi-Shalal, while a few states allow third-party lawsuits, yet there is

no consistent pattern among states that suggests a relationship between insurance rates

and the exercise of legal rights by third parties. Indeed, several states that prohibit third-

party lawsuits, such as Mississippi and North Dakota, have also encountered very high

rates of increase in recent years. Because California stands alone as the only state to see

decreases during the past twenty years, even as states with similar legal limits experienced

dramatic premium increases, it is clear that regulatory reforms – not civil justice

limitations – have been driving savings in California’s auto insurance market.

Insurers insist that premium savings have to be driven by reductions in claims and since

Proposition 103 regulates rates, rather than costs, the industry argues that legal

restrictions that drive down claims payments can be the only explanation for the savings.

Aside from the contradicting data above, this industry argument also ignores the critical

role Proposition 103 has played in driving down insurance costs.

Proposition 103 also created exceptional incentives for safe driving, incentives much

greater than those that exist in any other state.

$80

$90

$100

$110

$120

$130

$140

$150

$160

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

CALIFORNIA

COUNTRYWIDE

California

Countrywide

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 31

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

Proposition 103 magnified the benefits of safe, loss-reducing driving habits by:

1. Giving good drivers a 20 percent discount.

2. Implementing a rating system that requires that the greatest impact on a consumer's

final price derives from driving record. The second greatest impact on price must be

driving record and the third greatest impact must be years of experience, with all other

factors combined having less impact on the price than years of experience. Thus,

driving characteristics overwhelm all other factors in importance when it comes to the

cost of auto insurance only in California.

3. Prohibiting irrelevant factors that often lessen the importance of driving record. For

example, credit scoring cannot be used in California (in many states credit score has

more impact on price than driving record).

4. Empowering good drivers when they shop for auto insurance. Insurers are required

sell insurance to a good driver and must offer drivers the lowest price from among its

entire group of insurance companies. Thus, good drivers have great power when

shopping for insurance. In California, good drivers are really "in the drivers seat" when

it comes to auto insurance.

A significant number of Californians have realized that they have this power if they drive

carefully, leading to lower accident and claim frequencies over time and also leading to

more consumers finding and insisting on the best deals for insurance. These incentives to

safe driving and easier, smarter shopping are key drivers of Prop 103's astonishing

performance over the last quarter century.

In this way, Proposition 103 has lowered the cost of insurance by making it more valuable

and affordable to drive safely in California than any other state. But, under Proposition

103, there are several other mechanisms for lowering the costs of insurance that help

explain the decades of savings.

Proposition 103’s regulatory controls limit the ability of insurers to engage in profiteering,

wasteful expenditures and other inefficiencies. Proposition 103:

Limits the expense ratios of insurance companies, so they cannot pass on the costs of

inefficient or bloated administrative systems;

Limits the amount of executive salaries that can be passed on to customers;

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 32

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

Prohibits insurers from passing on the costs of lobbying, political contributions, bad-

faith lawsuits against the company, regulatory fines or institutional advertising, such as

corporate sponsorship of sporting events; and

Includes incentives to investigate and ferret out auto insurance fraud, such as staged

accidents.

Each of these cost-saving elements, in conjunction with the regulatory scrutiny of

Proposition 103, set California apart from the rest of the nation and explains the savings

realized by consumers over the past two decades. The fact that California’s civil justice

rules make California very much like the rest of the nation with respect to lawsuits against

insurance companies offers no such explanation.

D. Regulatory Standards of Excellence

In identifying California as the most consumer protective insurance regulation system in

the nation, we did not solely look at the change in rates. Low insurance rates alone do not

tell the entire story. In fact, low rates can sometimes be evidence of insufficient

enforcement of fair claims practices or evidence of predatory pricing that leads eventually

to inflated prices. California’s status as the consumer protection model is earned because

the state meets and often defines best practices across a range of categories – Regulatory

Standards of Excellence – that we reviewed.

The Standards

As part of our review, Consumer Federation of America considered the following list of Best

Practices that we have identified as measures of the quality of regulation generally and

insurance regulation specifically:

1. Fair and Transparent Regulation. Regulations should be easily understood by,

responsive and accountable to, and inspire confidence in, the public and regulated

companies and individuals.

2. Fair Competition. Regulations should promote beneficial competition that results in

fair profits for regulated companies, reasonable rates for ratepayers and the equitable

treatment of consumers.

3. Marketplace Equity. Regulations should reduce the problems associated with using

certain criteria – sometimes unjustifiably – to choose whether to insure some

policyholders and not others and at what cost. Regulations should also eliminate use of

risk classification factors that are not equitable or appropriate.

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 33

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

4. Freedom of Information. Regulations should ensure that key information is provided

to regulators, regulated entities and the public to allow them to identify market

problems and harmful practices.

5. Public Participation and Accountability. Regulations should encourage broad and

vigorous public involvement in the regulatory process, including institutionalized

consumer participation in the review of insurance rates, forms, and underwriting

guidelines.

6. Safe Products and Fair Practices. Regulations should result in the elimination of

harmful products, and unfair and deceptive practices in the marketplace, as well as the

provision of meaningful restitution to consumers harmed by these products and

practices.

7. Loss Prevention. Regulations should promote loss prevention and loss mitigation as

the most important way for insurers to manage risk and ensure safety and soundness.

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 34

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

Measuring California against Best Practices

A review of Proposition 103 and its rules illustrates where and how California has met and

often exceeded the standards, and why it stands out among all states as the most effective

regulatory system.

Fair and Transparent Regulation

Prior to Proposition 103, California had no meaningful regulation of insurance rates; there

was no requirement that rates even be filed with the Commissioner, much less be reviewed

or justified. Imagine the situation: through the antitrust exemption, insurers could collude

to set rates jointly, but the commissioner could not regulate (or even know about) insurer

prices. This was a prescription for the pricing abuse and inefficiency that occurred.

As a result, insurers could pass through all costs to consumers, no matter how unjustified.

They explained that their rates were "mirrors of society" and they passed through nearly

every penny, plus a percentage profit factor. This cost-plus-percentage-of-cost approach

gave insurers a perverse incentive; the larger the costs, the bigger the profit the percentage

add-on would produce.

Under California’s prior approval system, all auto insurance rates (and all property and

casualty insurance rates subject to Proposition 103) must now conform to a systematic set

of guidelines and methodologies for justifying the rates. Though the rules do not result in a

one-size-fits-all result, the regulatory structure is transparent and applied to all companies.

These rules set specific numerical or methodological constraints on the ratemaking process

to ensure that rates are not excessive or inadequate.

Perhaps most importantly, Proposition 103 authorizes the Insurance Commissioner to say

“no” to unjustifiable rate increases. It is important to note that the rules of Proposition 103

require insurance companies to maintain fair rates at all times. A common insurer

assertion that companies could reduce rates below current levels is not a viable critique of

the system but an admission that companies are violating the law. The Insurance

Commissioner, under these rules, can and should take immediate action to order rate

decreases when justified.

What Works: A Review of Auto Insurance Rate Regulation in America and How Best Practices Save Billions of Dollars

Page 35

Consumer Federation of America

consumerfed.org | @consumerfed

These “prior approval” regulations include the following:

1. Limit on Rate of Return. Under Proposition 103, insurance rates must be based on

data that project a rate of return that is based upon an average of returns on various

government bonds plus an additional 6 percent. As of November 2013, the maximum

rate of return that an insurer could build into its rate is 7.08 percent.

2. Efficiency Standard. Expense efficiency standards are determined by line and

distribution based on an average of the last three years of industry-wide expense data

expressed as a ratio of allowable underwriting expenses to earned premiums. The

standard “represents the fixed and variable cost for a reasonably efficient insurer to

provide insurance and to render good service to its customers.” For example, the

current efficiency standard for auto liability insurance sold by captive agents (such as

State Farm and Allstate) is approximately 35 percent, meaning that for every $100 of

premium charged to policyholders, an allowance is given to insurance companies of

about $35 to cover the cost of commissions to agents, other acquisition costs (e.g.,

advertising, etc.), general expenses (e.g., rent, salaries, etc.), premium taxes and fees

paid to the State of California and for the expenses of adjusting and settling claims other

than defense and cost containment expenses. For so-called “direct writers” (such as

Geico or 21

st