JULY 2022

DITCHING

LIGHT AIRCRAFT ON WATER

S

A

F

E

T

Y

S

E

N

S

E

SS21

The purpose of this leaflet is to provide guidance to GA pilots regarding ditching

light aircraft on water. It is primarily focused on the aeroplane pilot; although

much will be applicable to helicopters. Ditching is a deliberate emergency

landing on water, it is not an uncontrolled impact.

Ditching events beyond coastal waters are rare, but experience suggests that

if the aircraft impacts the water under control, the chance of survival is high.

There does not appear to be a statistical difference between high and low wing

aeroplanes.

Despite most impacts being survivable, occupants sometimes drown after

failing to vacate the aircraft or succumb to cold shock or hypothermia. It is

therefore important to consider post impact escape and survival.

YOUR SAFETY SENSE LEAFLET FOR:

DITCHING

2

CAA / July 2022

Safety Sense / 21 / Ditching

Sea temperatures will have a significant impact

on survival times. The temperature of the sea

around the UK will lag seasonal changes in the

outside air temperature, so is normally warmest

in September. The sea is coldest towards the

end of the winter in March. The sea temperature

in the winter will be around 8

o

C or less and

around 16

o

C by mid-summer. The North Sea and

eastern regions of the Channel tend to be colder

than areas to the southwest.

When planning to fly over a significant body of

water, consider the likely sea conditions below.

High winds, rain, poor visibility and heavy swell

will reduce the chances of a successful ditching

and rescue. The Met Office Shipping Forecast

is a good indicator of sea state conditions. An

explanation of the forecast and the ‘Beaufort

Scale’ can be found on the Met Office website.

DITCHING

Sea conditions

CAA / July 2022

3Safety Sense / 21 / Ditching

Likely survival time - person of average body mass without liferaft

INABILITY TO PERFORM TASKS WILL OCCUR LONG BEFORE DEATH

Survival suit with

long cotton underwear,

trousers, shirt

& heavy pullover

Average

winter

Average

summer

Time (hours)

Sea temperatures around UK

4

3

2

1

0ºC 5ºC 10ºC 15ºC

Lightweight summer

clothing

Death likely due to

cold shock before onset

of hypothermia

Even if you carry a life raft, consider the survival

times associated with being in the water before

rescue – in some ditchings, the raft is lost or

difficult to enter due to heavy swell.

In low sea temperatures, cold shock can cause

drowning and sometimes heart failure. This can

happen in a matter of minutes. Cold shock may

cause a gasp reflex, hyperventilation and an

increase in blood pressure. These responses will

likely diminish after several minutes if the head

can be kept above water and breathing can be

controlled.

Drowning can also be caused by ‘swimming

failure’, whereby the body’s reaction to the cold

water is to restrict blood flow to the extremities.

Even strong swimmers will lose the ability to

move their limbs effectively after a short period

of time and the swimming action will become

inefficient. This can result in the body adopting a

more vertical position in the water, at which point

the swimmer may panic and sink.

If in cold water for an extended period, the main

threat is hypothermia caused by a decrease in

body core temperature.

Contact with cold water is usually unavoidable

in a ditching and the effect can be mitigated by

wearing a survival suit. Removing yourself from

the water and into a life raft will significantly

extend the period before hypothermia sets in,

but it may not be possible if the body has already

succumbed to cold shock.

Survival times

DITCHING

CAA / July 2022

4Safety Sense / 21 / Ditching

Survival Equipment

DITCHING

Regulations

Part-NCO (Part-21 aircraft) and the Air Navigation Order (non-Part-21 aircraft) contain equipment

requirements for flight over water. Lifejackets for all onboard are required when in an aircraft beyond

gliding range of land, or if in the opinion of the pilot in command, the planned flight path during takeoff

or landing is near water, such that a ditching may occur in the event of an emergency. You should

know your aircraft’s gliding or autorotation range.

When flying more than

30 minutes or 50 NM

from land (whichever is

less), the pilot in command

is required to assess

the survival equipment

necessary to carrying on

the flight.

Such an assessment

should consider the sea

state and temperature,

weather conditions,

distance from land and the

availability of search and

research services.

Equipment that may be deemed necessary could include distress signals, such as lights or flares, life

rafts for all persons onboard and any life-saving equipment such as drinking water or first aid kits.

After reviewing this leaflet and assessing the flight, it is recommended to determine a

list of items you feel are appropriate – the regulations do not specify all the detail, so a

degree of personal judgement is required.

The UK AIP GEN 3.6 details Search and Rescue provision in the UK. GEN 3.6 is the normal ICAO

assigned AIP section for Search and Rescue provision and will be detailed there by most states.

CAA / July 2022

5Safety Sense / 21 / Ditching

DITCHING - SURVIVAL EQUIPMENT

Life Jackets

Life jacket selection

Only use lifejackets intended for use in light

aircraft. Lifejackets should be designed for

constant wear and have a protective covering

over the uninflated buoyancy chambers. A

suitable lifejacket provides around 150 newtons

of buoyancy, which should be enough to keep an

unconscious person afloat with the head above

water. Check suitability for children or infants,

you will likely need a lifejacket or floatation

device designed for a smaller body size.

Airline style jackets are only suitable for occasional

use – when worn uninflated they lack any

protection from accidental tearing or other damage

from constant wear. Lifejackets intended for

marine use often inflate automatically on contact

with water – this feature is unsuitable in an aviation

environment since the jacket may inflate in the

aircraft and make it impossible to escape.

Non-inflating ‘buoyancy aids’ used for leisure

boating or similar are also unsuitable – the passive

buoyancy will impede exit but will not usually be

sufficient to keep an unconscious person floating

with the head held above the water.

It is recommended that lifejackets have the

following features:

> Light;

> Whistle;

> Crotch strap;

> Spray hood; and

> Reflective markings

Lifejackets should be serviced annually by a

competent organisation – the original vendor of

the jackets should be able to advise on this.

Wearing the life jacket

In a single engine piston aircraft, all occupants

should wear their lifejackets in flight. The

lifejacket should normally be donned prior to

entry into the aircraft and seatbelts should be

fastened over the jacket.

In the case of twin engine aircraft, carriage

under the seats or other accessible location is

acceptable but consider how practical it will be

to don lifejackets in a timely fashion during an

emergency. Passengers must briefed on how to

don lifejackets inside the aircraft and ensure they

will not become entangled in the seatbelts.

Consider that some ditchings, including with

multi-engine aircraft, have occurred due to fuel

starvation, fire, control difficulties or factors aside

from engine failure.

CAA / July 2022

6Safety Sense / 21 / Ditching

DITCHING - SURVIVAL EQUIPMENT

Life rafts

Life raft selection

Life rafts should be designed for aviation use.

The inflation cylinder for the raft should be

designed to vent into the air (rather than inflate)

in the event of a malfunction

1

. Inflation of the raft

inside the cabin could be very dangerous.

It is recommended that the life raft has a canopy

to reduce the effects of exposure. An integral

canopy that erects itself on inflation is best and

may make it easier to right the raft if it inflates

upside down, since the canopy will prevent it

from completely inverting in the water. Many

life rafts also include some survival equipment

inside, which is useful since it does not need to

be carried separately – it should be listed in the

documentation with the raft.

A boarding aid such as a rope ladder at the

entrance will make it easier to climb in. Ensure

the raft occupancy capacity is sufficient for the

number of occupants on the aircraft.

As with lifejackets, rafts should be serviced

annually, or as directed by the manufacture’s

recommendations.

A good quality raft is quite expensive, so some

companies offer short or long-term hire, which may

be more cost effective for the occasional user.

Carriage of the raft

If crossing any significant body of water, it is

strongly recommended to carry a life raft, in

addition to wearing life jackets. A raft should allow

the survivors of a ditching to remove themselves

from the cold water, which could significantly

improve the likelihood of survival.

When carrying the life raft in the aircraft, secure

it (for example with a seatbelt) in an accessible

location where it will not interfere with the controls.

Include it in any weight and balance calculations –

some rafts weigh more than 15 kgs.

1

It is still wise to consider the event of an accidental inflation in the cabin, for example puncturing it with a knife or other sharp object may be necessary

CAA / July 2022

7Safety Sense / 21 / Ditching

DITCHING - SURVIVAL EQUIPMENT

Survival Suit

A survival or immersion suit designed for aviation

use will significantly improve survival prospects in

cold waters. Whilst some pilots may feel that this

level of protection is ‘over the top’ for a cross-

Channel flight, there have been cases where

lives have been saved by the wearing of such

clothing, particularly during periods of lower sea

temperatures.

If the survival suit used is an uninsulated ‘dry suit’,

it will keep the water out, but to be fully effective

from the cold you will need to wear warm clothing

underneath to create layers of air that trap your

body heat.

Even if you carry a raft, it may be lost or damaged

in the ditching. Experience has shown that it is

often difficult to enter a raft during high winds and

heavy swell. The raft may also be lost or damaged

in the impact, so wearing a survival suit is still wise

precaution.

Clothing

If a survival suit is not worn, high insulation

clothing which traps air can still improve

chances of survival in the water. Woollen

clothing may be cumbersome when wet, but it

retains around 50% of its insulating properties

compared to wet cotton which is only 10% of

its dry insulation. Warm headwear will prevent

body heat escaping from your head.

CAA / July 2022

8Safety Sense / 21 / Ditching

DITCHING - SURVIVAL EQUIPMENT

It has been a requirement since 25th August 2016

for a Part-21 aircraft to have an emergency locator

beacon (ELT) fitted. For aircraft fitted with up to six

passenger seats, a portable locator beacon (PLB)

may be carried instead, although for overwater

flights it is recommended to have both devices.

The PLB should have a GNSS receiver and

broadcast on both 406 MHz and 121.5 MHz. The

PLB must be registered with the appropriate

authority. Features such as buoyancy are also

recommended.

Most fitted ELTs are activated on impact, although

it may be possible to manually active prior to

ditching. Some fixed ELTs will also activate

on contact with water. You should check the

specification fitted to your aircraft. For PLBs, be

familiar with the operation of your device and keep

it readily accessible during flight. Comply with any

manufacturer instructions for testing and servicing.

Survival accessories

Ditching bag

There are no hard rules in terms of what should be carried, but items such as a portable

VHF radio, flares, high power strobe, first aid kit, knife, signalling mirror, sea sickness

tablets, water and small amounts of high energy food should be considered.

It is a good idea to carry a waterproof bag that contains items such as the PLB, your

phone and the survival equipment. Brief passengers on its location and contents.

ELT or PLB

ELT

PLB

CAA / July 2022

9Safety Sense / 21 / Ditching

Preparation

DITCHING

You may have all the right equipment, but you need to know how to use it effectively and brief all

occupants on what to do in the event of a ditching. The equipment also needs to be serviceable and

accessible for use.

Passenger Briefing

Part-NCO, and the Air Navigation Order for non-Part-21 aircraft, require that passengers

are briefed on the safety and emergency procedures for the flight. Include all normal

items such as operation of doors and seatbelts (see SSL 02, Care of Passengers).

For flights over water also cover:

> Use of lifejackets, including to only inflate once outside the aircraft;

> Location and use of the life raft. Allocate someone to be responsible

for taking the life raft from the aircraft in a ditching;

> Use of the ELT/PLB;

> Preparation for impact, such as brace position, tightening

seatbelts, removing headsets and stowing eyeglasses;

> The order in which people should evacuate the aircraft;

> Reference points on the aircraft’s structure to reach for when exiting

the aircraft as well as any features which might impede exit;

> The most effective way of opening doors if submerged; and

> Actions when clear of the aircraft.

Ditching courses

Flight Planning

If you fly over water often, you should consider attending a ditching survival course.

In a safe environment you will be taught the correct operation of lifejackets, methods

of getting into life-rafts and the problems you might encounter after a ditching. Some

specialist companies have light aircraft shaped ‘dunkers’ to practise underwater escapes.

The cold and dark of a submerged aircraft is a very disorientating environment, so having had

some practice, your chances of survival will be improved should the worst ever happen.

Fly as high as possible, this will give you more time in a ditching and may allow you to

get closer to land. Radio reception will also be better. Consider taking a longer route to

avoid exposure to a long water crossing. As you approach the sea, check the engine

instruments to ensure everything is normal.

CAA / July 2022

10Safety Sense / 21 / Ditching

Surviving a Ditching

DITCHING

Maintaining Control

Aircraft ditch for various reasons, it may be an

engine failure, but there could be other factors

such as fire.

Should the worst happen, remember to

keep flying the aircraft. As per any emergency

situation, Aviate, Navigate and Communicate,

in that order.

Carry out any emergency procedures from the

aircraft flight manual that may recover the situation,

such as changing fuel tank or turning the fuel pump

on. A common cause of ditching is fuel starvation,

but often the fuel system was not correctly

configured and there was still usable fuel onboard.

Once you have established you are in a ditching

scenario, fly at best glide speed (if applicable) and

turn towards the nearest coastline. If you are far

from land, look for shipping. Small to medium sized

vessels are preferable, large ships may not be able

to stop in proximity to the ditching point and will be

of limited assistance. If ditching near a ship, ahead

but to the side of their path is best.

With the aircraft under control, transmit a Mayday

call on the active frequency, or 121.5 MHz if you

are not in contact with ATC. Set transponder code

7700. Give your situation, position and intentions.

Landing technique

The swell direction is normally more important than wind direction when planning a ditching. Swell

refers to the parallel lines of waves in the sea, which will typically be moving in the same direction.

Below 2,000 ft, the swell direction should be apparent. Aim to touch down parallel to the line of the

swell, attempting to land along the crest of the wave or slightly behind it.

The table below describes sea states and how to approach them:

Wind Speed Appearance of Sea Effect on Ditching

0-6 knots

(Beaufort 0-2)

Glassy calm to small ribbles. Height very difficult to judge above

surface. Ditch parallel to swell.

7-10 knots

(Beaufort 3)

Small waves; few if any white caps. Ditch parallel to swell.

11-21 knots

(Beaufort 4-5)

Larger waves with many white

caps.

Use headwind component, but still

ditch along general line of swell.

22-33 knots

(Beaufort 6-7)

Medium - large waves, some foam

crests, numerous white caps.

Ditch into wind on crest or

downslope of swell.

34 knots & above

(Beaufort 8+)

Large waves, streaks of foam,

waves crests forming spindrift.

Ditch into wind on crest or

downslope of swell. Avoid at all

costs ditching into the face of the

rising swell.

CAA / July 2022

11Safety Sense / 21 / Ditching

DITCHING - SURVIVING A DITCHING

High Winds

If you can see spray and spume on the surface,

then the surface wind is strong. In this case it

is probably better to land into wind, rather than

along the swell. Winds of 35 to 40 kt are generally

associated with spray blowing like steam across

waves and in these cases the waves could be

10 ft (3m) or more in height. Aim for the crest or

failing that, into the downslope. You need to avoid

being hit by a wave from above.

Preparing for impact

Review with your passengers the key points

of the landing and egress. Ensure seat belts

are tight. Headsets should be removed before

touchdown. Passengers without an upper body

restraint should adopt the brace position just

prior to impact. Ensure all survival equipment is

accessible. Consider unlatching a door to reduce

the risk of it becoming jammed.

Landing Technique

The Aircraft Flight Manual/Pilot’s Operating

Handbook may provide suitable guidance, if the

AFM conflicts with statements in this leaflet,

follow the AFM.

The force of impact will be high so ditch as

slowly as possible whilst maintaining control.

Land tail down at the lowest possible forward

speed, but do not stall into the water. It is

important to keep the wings level, if a wing tip

catches the water first the aircraft will likely

spin or cartwheel. The use of flap is advisable to

minimise the touchdown speed.

It may be difficult to judge your height above

the water, for example if the sea is calm with a

‘glassy’ appearance or if visibility is poor. In this

case, once at low level reduce speed below best

glide but keep a margin above the stall – this will

minimise the aircraft’s sink rate while retaining

control. Hold the descent attitude until impact.

If some power is available from the engine,

use it to reduce the descent rate. Some AFMs

recommend always using a steady sink descent,

rather than flaring, to avoid misjudging the height

of the water.

There will likely be several ‘skips’ along the

top of the water before the main impact. The

deceleration will be very harsh and the nose will

tip downwards. Water will rush over the nose

and windscreen. It may smash the windscreen,

letting water in rapidly and giving the impression

of the aircraft sinking.

Landing technique (continued)

CAA / July 2022

12Safety Sense / 21 / Ditching

DITCHING - SURVIVING A DITCHING

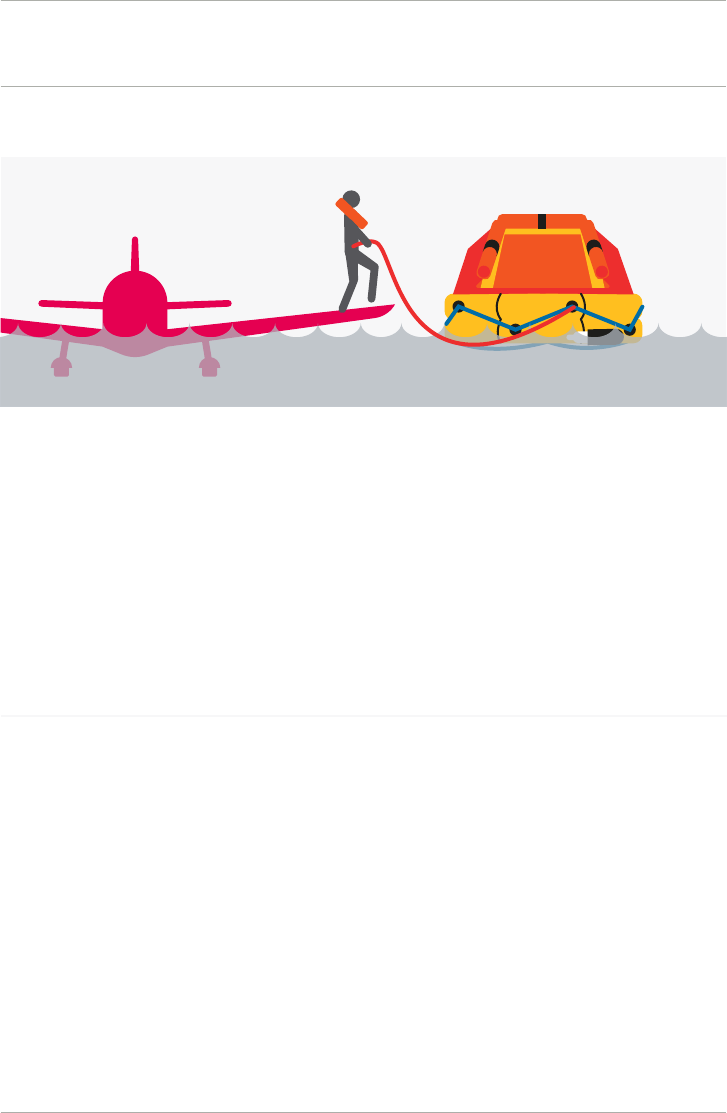

The natural buoyancy of the uninflated raft may

make it hard to manoeuvre out of the aircraft. Keep

hold of it by the cord, but do not inflate the raft

immediately – doing so before being prepared will

result in it blowing away.

Once inflated, currents and wind will immediately

try to move the raft away from you and may invert

it. If practical, the person with the raft should hold

onto the aircraft when inflating it, so as not to be

dragged away.

Check the manufacturer’s recommendations

for securing the raft while boarding – tying it to

someone’s belt or lifejacket harness is one option

but if the aircraft is still afloat, it may be more

effective to initially tie it to a wing strut or exterior

handle. Most rafts have a tear patch at the cord

attachment point that should break off to prevent

the sinking aircraft dragging it down.

If the sea state allows, getting into the raft by

standing on the wing or other part of the aircraft will

normally be easier than from the water. Position

the raft near to the aircraft and take account of the

wind direction – you do not want the raft blowing

towards you or the aircraft structure (which may

damage it), but if you position it downwind it may

blow away and be harder to enter.

Vacating the aircraft

Inflating the life raft

With a high-wing aircraft, it may be necessary

to wait until the cabin has filled with water

before it is possible to open the doors – only

wait for water to enter as a last resort though.

If you cannot open the doors, open or kick out

windows before you are underwater. Be aware

of any panels designed to be pushed out in an

emergency. Keeping you seatbelt fastened after

the initial impact may allow you to apply more

force to open the doors and windows.

The shock of cold water may adversely affect

everyone’s actions. Therefore, a pre-flight

passenger briefing which emphasises interior

reference points and the agreed order in which

to vacate the aircraft is vital. Do not inflate

lifejackets inside the aircraft, inflate them as

soon as you are outside.

Consider leaving the master switch and the

anti-collision beacon or strobes on. If the aircraft

floats for a while or sinks in shallow water, the

lights may continue operating and provide some

light and indication of your position. Exit the

aircraft as swiftly as possible, remembering to

take the raft and ditching bag if carried.

CAA / July 2022

13Safety Sense / 21 / Ditching

Dealing with a capsized raft

DITCHING - INFLATING THE LIFE RAFT

It is possible that the raft will inflate upside down

or that the wind will blow it over. Should you need

to turn it upright, position yourself downwind of

the raft.

If it is floating partially on one side, position yourself

by the underside that is resting in the water and

move the raft so that the wind is blowing in the

same direction as you want to tip it.

Wind

Alternatively, standing on the aircraft may allow you to reach the high side of the inverted raft and pull it over.

The inflation cylinder is normally attached on the

bottom of the raft or to the side of the base.

Rotate the raft such that the cylinder is at the low

point next to you. Push down at this point and grab

any righting straps on the underside of the the raft.

Pull the high side down towards the water. The

weight of the cylinder and the wind should help

turn it over. As it falls towards you move out of the

way and grab hold of the side to prevent it floating

away.

CAA / July 2022

14Safety Sense / 21 / Ditching

DITCHING - INFLATING THE LIFE RAFT

Entering the raft

The raft should have a recommended entry point

and sometimes a rope ladder to assist entry.

Remove any items such as high heeled shoes that

may damage the raft. If you must enter the water

before climbing into the raft, hold the bottom of

your lifejacket with one hand and place the other

hand over your mouth and nose to reduce the

intake of cold water.

Assisting others

Some survivors may struggle to climb into the

life raft from the water. The most physically able

survivors may need to enter the raft first to assist

others with entering.

If someone is struggling to climb in, position them

with their back against the entrance point and then

grip them under the armpits from behind (not by

the arms) – this will be easier with two people in

the raft to lift them. Anyone else in the raft should

move to the opposite side to the entrance, to

provide balance. Initially the person in the water

should be pushed down to create a resistance

against the buoyancy of their inflated lifejacket.

Then pull them sharply back up again

– the buoyancy should give a spring effect

to aid lifting them in.

As more people enter the raft, they should

distribute themselves around the perimeter to

stabilise it most effectively.

Securing the raft

Once everyone is aboard the life raft, there may be

some additional actions to complete. You may need

to separately inflate the floor, buoyancy chambers

and trail the drogue or sea anchor. A sea anchor is

designed to stop the raft drifting.

If not already in place from the inflation, erect

the canopy to protect the occupants from the

wind and spray.

CAA / July 2022

15Safety Sense / 21 / Ditching

Waiting for rescue

DITCHING

Remove as much water from the raft as possible. Try to remove water from clothes by

wringing them out. If available, take sea sickness tablets immediately to reduce the risk

of vomiting. The raft may have these in the survival equipment pouch. In the confines

of the raft on a rough sea, survivors will likely feel nauseous and vomiting will cause

the loss of vital fluids and energy. Due to the salt content, do not drink sea water, it will

accelerate dehydration.

Deploy your PLB. Follow any instructions such as keeping the aerial vertical with a clear

view of the sky - if necessary position the aerial through a gap in canopy. If your phone

has survived the ditching and you are within network coverage, diall 999 (in the UK)

and ask for the coastguard. With marginal signal, a text message to a friend or family

member may also work.

Use any visual signalling equipment you have, but do not waste battery power or

flares by setting them off when there is no one to observe them. However, if you have

ditched in a busy area of the Channel for example, visual signals may be spotted quite

soon. Flares should be held at arm’s length, outside and pointing away from the life raft

as they often leave hot deposits. If you have any gloves or other protection, use them to

protect your hands.

Water dye that makes the raft’s location more visible from the air may last around three

hours, or less in rough seas, so do not deploy it immediately. If the sun is visible, a

heliograph mirror can create a strong visual signal.

Assuming you were able to give an accurate location to ATC prior to ditching, search and

rescue should be able to find you, but it could still take hours before you are lifted from

the water. Some rafts will have a small aperture in the cover that can be opened to look

out and show signals, so take it in turns to conduct a watch for rescuers.

PLB

CAA / July 2022

16Safety Sense / 21 / Ditching

Without a raft

DITCHING

Conserving Heat

The most critical areas of the body for heat loss are

the head, sides of the chest and the groin region.

If the lifejacket has one, cover your head with the

spray hood to reduce the risk of drowning.

Do not swim to keep warm. The increase in blood

circulation in the arms, legs and skin will just

transfer more heat to the cold water.

In a group of survivors, tie yourselves to each other

and huddle with the sides of your chests and lower

bodies pressed together. If there are children,

sandwich them within the middle of the group for

extra protection.

Without a life jacket

If you end up in the water without a lifejacket,

try to find some debris such as a seat cushion or

luggage that will give buoyancy. Keeping afloat

without anything to provide buoyancy will be

exhausting. Even an inflated plastic bag may be

better than nothing.

Lone survivor

A lone survivor should adopt the ‘HELP’ position

(Heat Escaping Lessening Posture). This position

will increase your survival time. Hold the inner

sides of your arms in contact with the side of the

chest. Hold your thighs together and raise them

slightly to protect the groin region.

Attracting attention

Survivors in the water can be difficult to spot.

When you see a search aircraft or nearby ship,

signal with any devices you may have such as

lights, flares or a heliograph mirror. Even splashing

the water with your arms may attract attention

as disturbed water may reflect off the beam of

a search light. A whistle is more effective than

shouting.

If you are without a raft or it is unusable for some reason, this decreases the chances of survival, but do

not give up hope – the will to survive is the most powerful force to prolong life.

Tie important survival items such as the PLB to someone’s life jacket. Try and keep the aerial of the PLB

vertical. The cold will cause restriction of movement very quickly, so perform any manual tasks while you

are still able.

CAA / July 2022

17Safety Sense / 21 / Ditching

The rescue

DITCHING

When help arrives, stay where you are and follow any instructions from the rescuer. Do not try to do things

on your own initiative.

If a helicopter is making the rescue, wait for instructions from the winchman. For example, do not reach

out and touch the winch cable without being instructed to. The winchman will normally descend on the

cable to supervise the winch. When being winched up, do not touch the cable or the helicopter, the crew

will manoeuvrer you up and inside as required.

If possible, deactivate your PLB once safely onboard the helicopter or rescue boat. The PLB signal on

121.5 MHz will often be heard by commercial aircraft monitoring the frequency, who may report it to ATC,

so deactivating it may avoid any unnecessary confusion.

Survival Equipment

Always wear lifejackets over water

Carry a Personal Locator Beacon (PLB)

Consider equipment such as a life raft and survival suits

Preparation

Minimise the time over water

Consider the weather and sea conditions

Brief your passengers

The Ditching

Know your aircraft’s technique

Declare an emergency

Have an escape plan

Surviving at sea

Know how to use your equipment

Activate your PLB

Consider cold water survival

SUMMARY

CAA / July 2022

18Safety Sense / 21 / Ditching