PUBLIC

MONE

FOR

PRIVATE

EQUIT

PANDEMIC RELIEF EN O

COMPANIE BACKED

B PRIAE EQI IAN

Americans for Financial Reform Education Fund (AFREF) is a nonpartisan, nonprofit

coalition of more than 200 civil rights, community-based, consumer, labor, small

business, investor, faith-based, civic groups, and individual experts. We fight for a fair

and just financial system that contributes to shared prosperity for all families and

communities.

www.ourfinancialsecurity.org

The Anti-Corruption Data Collective (ACDC) brings together leading journalists, data

analysts, academics and policy advocates to expose specific dimensions of

transnational corruption flows and work to undermine those flows through the

advocacy reach of ACDC partners.

www.acdatacollective.org

Public Citizen is a national non-profit organization with more than 500,000 members

and supporters. We represent consumer interests through lobbying, litigation,

administrative advocacy, research, and public education on a broad range of issues

including consumer rights in the marketplace, product safety, financial regulation,

worker safety, safe and affordable health care, campaign finance reform and

government ethics, fair trade, climate change, and corporate and government

accountability.

www.citizen.org

Public Money for Private Equity: Pandemic Relief Went to Companies

Backed by Private Equity Titans

AUTHORS

Americans for Financial Reform

Education Fund

Oscar Valdes-Viera

Patrick Woodall

Anti-Corruption Data Collective

David Szakonyi

Public Citizen

Miriam Li

Taylor Lincoln

Michael Tanglis

The authors thank the Project on

Government Oversight for graciously sharing

data from their COVID-19 Relief Spending

Tracker, and Good Jobs First for sharing

data on the health care industry.

Every effort has been made to verify the

accuracy of the information contained in this

report. All information was believed to be

correct as of September 3, 2021.

Nevertheless, the authors cannot accept

responsibility for the consequences of its use

for other purposes or in other contexts.

2021 Anti-Corruption Data Collective, a

project of the Fund for Constitutional

Government.

Except where otherwise noted, this work is

licensed under CC BY-ND 4.0. Quotation

permitted.

Contents

1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................... 2

2. PRIVATE EQUITY-BACKED COMPANIES RECEIVED $5.3 BILLION IN

PANDEMIC RELIEF .......................................................................................... 8

A. Private Equity-Backed Healthcare Companies Received $3.9 Billion. .............................. 10

B. Private Equity Captured $1.2 billion in Funds Earmarked for Small Businesses ................. 16

C. Private Equity’s Lobbying Efforts Helped Secure Access to Public Funds ......................... 21

3. PRIVATE EQUITY WAS POSITIONED TO THRIVE DURING THE PANDEMIC

WITHOUT PUBLIC SUPPORT ........................................................................ 24

4. PRIVATE EQUITY’S PREDATORY PRACTICES HAVE BEEN ESSENTIALLY

SUPPORTED BY PUBLIC MONEY .................................................................. 27

A. Private Equity-backed Companies Accepted Public Support but Shed Workers ............... 28

B. Private Equity Firms Pursued Hundreds of Takeovers During the Pandemic ..................... 30

C. Private Equity Firms Took Dividends out of Companies that Received Pandemic Relief ... 34

D. Private Equity Firms Charged High Fees to Portfolio Companies Struggling in the Pandemic

............................................................................................................................................ 36

E. More Public Aid Flowed to Portfolio Companies than Some Private Equity Firms Paid in

Taxes ................................................................................................................................... 36

5. CONCLUSIONS & RECOMMENDATIONS .......................................................... 39

6. METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................... 41

7. ENDNOTES ....................................................................................................... 45

PUBLIC MONEY FOR PRIVATE EQUITY

2

1. Executive Summary

This study estimates that at least $5.3 billion in CARES Act money

went to 611 portfolio companies owned or backed by private

equity firms that held $908 billion in cash reserves.

Hundreds of companies owned or backed by some of the largest, best financed private

equity firms secured an estimated $5.3 billion in public funding under the Coronavirus

Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. Federal pandemic relief efforts

provided trillions of dollars in response to the twin public health and economic crisis.

Yet the legislation imposed few conditions on recipients — such as requirements to

support workers and maintain business operations — and failed to prohibit recipients

from using public money to enrich investors.

This lack of binding statutory requirements has enabled the private equity industry to

continue its typical extractive and predatory practices. Private equity firms take over

companies as investment vehicles, and then use aggressive tactics and financial

engineering that often undermine the portfolio companies’ financial viability. They

frequently extract substantial value from their takeover targets through debt-financed

leveraged buyouts, excessive fees, dividends, and stripping out valuable assets such

as real estate. Workers, consumers, and patients pay the price for the aggressive cost-

cutting strategies that private equity firms use to siphon revenues from the companies

they own.

Public money for private equity-backed companies not only went to companies that

already had deep-pocketed backers, but also effectively allowed private equity owners

to continue and even expand their predatory tactics during an economic and public

health emergency. With improved balance sheets shored up by government money,

private equity firms were able to finance a buyout spree during the pandemic-driven

economic downturn as well as to extract dividends and fees from their portfolio

companies.

PANDEMIC RELIEF WENT TO FIRMS BACKED BY PRIVATE EQUITY TITANS

3

The private equity industry captured funds that should have supported small,

independent businesses, especially those owned by women and people of color.

Private equity firms could have tapped their own cash reserves (known as dry powder)

to help their portfolio companies, which would have left more public resources

available to help other struggling companies, especially smaller businesses owned by

women and people of color.

This study estimates that 611 portfolio companies received nearly 16,000 CARES Act

loans or grants worth at least $5.3 billion. These portfolio companies were owned or

backed by 113 private equity firms that collectively held $908 billion in cash reserves.

It is a conservative estimate, because this analysis looked only at private equity firms

with more than $5 billion in assets under management and because the opacity of the

private equity industry makes it impossible to make a comprehensive list of private

equity-backed companies that may have received pandemic relief. Private equity firms

buy and sell assets — including entire companies or single facilities — constantly and

it is not possible to have a perfect list of portfolio firms based on publicly available

information at any one point in time.

Our calculations rely on information on specific recipients of CARES Act funding

through December 2020 from the Project on Government Oversight (POGO), which

graciously shared the data collected through its COVID-19 Relief Spending Tracker.

(The data sources and analytical approach are fully described in the Methodology

appendix on page 41.)

Nearly all of the funding for private equity-backed companies came through the CARES

Act programs operated by the Department of Health and Human Services ($3.7 billion

or 69 percent), the Small Business Administration ($1.2 billion or 23 percent), or the

airline payroll protection program ($341 million or 6 percent).

Even within the private equity industry, a small number of large investors dominated

access to CARES Act funds. Over $4 billion (76 percent of the total pandemic relief to

the industry) went to portfolio companies owned by just 10 private equity firms.

Leading the way, companies backed by the private equity firm Apollo Global

Management (Apollo) received $1.4 billion. The portfolios of Cerberus Capital

Management (Cerberus) received $883 million and Welsh, Carson, Anderson & Stowe

received $436 million. In total, these top ten private equity firms reported $245 billion

in dry powder cash reserves during 2020 that could have shored up their own portfolio

companies, meaning they did not need to take public funding.

PUBLIC MONEY FOR PRIVATE EQUITY

4

This report identifies some of the more troubling and problematic practices which

were essentially tolerated or facilitated with public support. Key findings include:

More than $5 billion in pandemic relief went to the largest

private equity firms:

At least $5.3 billion in CARES Act loans or grants went to 611 portfolio

companies owned or backed by 113 private equity firms that each had more

than $5 billion in assets.

Private equity-backed healthcare companies received

$3.9 billion but continued many practices that undermine

patient health and finances:

143 private equity-backed hospitals, physician groups, and other health

companies, received over $3.9 billion in pandemic support, including some

troubled hospital chains and companies responsible for surprise medical

billing, charging patients out-of-network fees for services like ambulance rides,

emergency room visits, or x-rays at in-network hospitals or clinics. At the

height of the pandemic, Cerberus’ Steward Health Care threatened to close its

hospital in Easton, Pennsylvania, if it did not receive a $40 million public

bailout. The state wound up having to pay the hospital $8 million to keep it

open for four weeks and provide essential healthcare services.

Private equity-backed companies secured $1.2 billion in

pandemic relief that was intended for small businesses:

The small business programs included exemptions that allowed private

equity-backed companies to access public funding that should have gone to

genuinely small and independent businesses. A large amount of this funding

($224 million) went to private equity-backed fast-food and other restaurant

chains that prospered during the pandemic while thousands of independent

restaurants closed forever. Some small business money went to private

equity-backed chains that were already financially compromised, including Art

Van Furniture and Chuck E. Cheese — both of which collapsed under private

equity-imposed debt. In fact, Art Van received public support although it was

already in bankruptcy.

PANDEMIC RELIEF WENT TO FIRMS BACKED BY PRIVATE EQUITY TITANS

5

Largest private equity firms held $908 billion and

were well positioned to thrive without public support:

The private equity firms included in this study had $908 billion in cash reserves

known as dry powder during 2020, meaning that they could have helped their

portfolio companies to weather the pandemic without relying on public

funding.

Largest private equity firms and trade association

spent $32 million in lobbying around the CARES Act:

Eighteen private equity firms and the industry’s primary trade association

spent almost $32 million on lobbying during 2020, including on pandemic

related issues, based on lobbying disclosures data.

Some private equity-backed companies

that received support shed workers during the pandemic:

Apollo-owned LifePoint Health received over $1.4 billion in public support yet

furloughed workers at its hospitals around the country. Blackstone Group’s

TeamHealth reduced hours for emergency room workers at a number of its

facilities, and even went as far as firing one ER doctor in Seattle after he

warned about the lack of personal protective equipment and unsafe working

conditions. TeamHealth received more than $2.8 million in pandemic relief.

The CARES Act aviation payroll protection program was the only program that

did have strong provisions to make sure that workers kept their jobs and

benefits during the pandemic. Private equity-backed air transport companies

received $341 million in pandemic relief, but three of the firms that the House

Select Committee on the Coronavirus Crisis identified as firing workers after

agreeing to accept payroll support funding were backed by private equity

firms. Two were owned by the Carlyle Group and one was owned by JLL

Partners, see airline workers box on page 29.

.

PUBLIC MONEY FOR PRIVATE EQUITY

6

Private equity firms whose portfolio companies received

public support pursued new leveraged buyouts:

The private equity industry made a wave of highly profitable leveraged

buyouts in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. During the pandemic, the

industry similarly capitalized on the economic downturn by aggressively

buying up companies. The 10 private equity firms whose portfolio companies

received the most public money executed 230 leveraged buyouts from March

to December 2020, with a disclosed value of more than $45.1 billion. For

example, Roark Capital Group bought Dunkin’ in an $11.3 billion buyout in

October 2020 after the chain received $27 million in public support.

Private equity firms extracted dividends and fees

from portfolio companies that received pandemic relief:

There were no provisions in the CARES Act that prevented private equity firms

from extracting fees or debt-funded cash dividends from their portfolio

companies. At least five private equity firms extracted dividends from

companies that received pandemic relief. One such company, DuPage Medical

Group, received $79 million in CARES Act funding and paid a $209 million

dividend to its owners, including Ares Management Corporation’s private

equity arm (Ares). Private equity firms also continued to charge exorbitant

management fees to their portfolio companies during the pandemic, including

those that received millions in public support after claiming financial distress.

Publicly traded Apollo, Blackstone, Carlyle Group, and Kohlberg, Kravis and

Roberts (KKR) disclosed a combined $5.4 billion in management fees in 2020

even as their portfolio companies received $1.8 billion in public aid.

Several private equity firms got more in pandemic

aid to their portfolio companies than they pay in taxes:

Private equity firms receive beneficial tax treatment that significantly lower

their effective tax payments. The portfolio companies of Apollo, Ares, Carlyle,

and KKR received more public support than the private equity firms paid in

taxes. The Apollo portfolio companies received nearly 50 times more in

pandemic relief ($1.4 billion) than the firm’s average tax payments of $30

million between 2018 and 2020.

PANDEMIC RELIEF WENT TO FIRMS BACKED BY PRIVATE EQUITY TITANS

7

This report first describes the main findings on the volume of pandemic relief money

going to private equity backed portfolio companies, with detailed explanations of

assistance given to healthcare companies and small businesses. A short history of the

private equity industry on the eve of the pandemic then lays out the strong financial

position that many private equity firms were in prior to receiving public money. The

report then outlines five predatory practices that the private equity industry uses to

enrich investors, all of which continued after CARES Act money was distributed to their

portfolio companies. The report concludes with a list of recommendations to

strengthen the guardrails on accessing public money from future relief efforts.

PUBLIC MONEY FOR PRIVATE EQUITY

8

2. Private Equity-Backed Companies

Received $5.3 Billion in Pandemic Relief

This study estimates that $5.3 billion in CARES Act loans or grants went to 611 portfolio

companies owned or backed by 113 private equity firms (those with more than $5

billion in assets under management) that collectively held $908 billion in cash reserves.

The largely opaque private equity industry makes it impossible to make a precise

determination of the number of private equity-owned or -backed companies that may

have received funding under the CARES Act, but these numbers reflect a conservative

estimate of the public support that flowed to the companies owned or backed by the

largest private equity firms during the pandemic.

Almost all of this funding came through the programs operated by the Department of

Health and Human Services (HHS) ($3.7 billion or 69 percent), the Small Business

Administration (SBA) ($1.2 billion or 23 percent), and the Treasury Department’s airline

workers relief program ($341 million or 6 percent — see Figure 1). Unsurprisingly,

healthcare companies received more than two-thirds of the pandemic relief funding

(73 percent), followed by air transportation companies (6 percent), restaurants (4

percent) and energy companies (2 percent, see Energy Box on page 14).

PANDEMIC RELIEF WENT TO FIRMS BACKED BY PRIVATE EQUITY TITANS

9

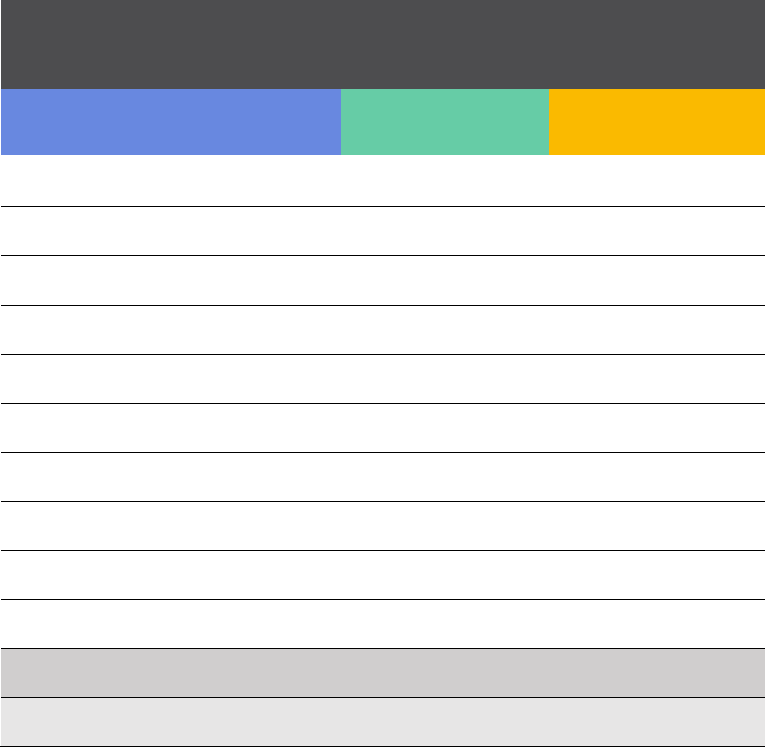

TABLE 1: TOP 10 PRIVATE EQUITY FIRMS WHOSE PORTFOLIO

COMPANIES RECEIVED THE MOST PANDEMIC RELIEF

Private Equity Firm

No. Awards

Pandemic Relief ($M)

Apollo

362

$1,489.3

Cerberus

71

$883.3

Welsh, Carson, Anderson & Stowe

309

$436.3

TPG Capital

746

$428.6

Leonard Green & Partners

253

$419.3

Kohlberg Kravis Roberts

447

$198.4

Roark Capital Group

7530

$183.4

Ares Capital

172

$164.8

Bain Capital

146

$142.1

Carlyle Group

16

$131.0

Source: POGO Database

Most of the funds (60.1 percent) were loans or loan guarantees with the rest coming

as direct payments or grants (39.9 percent). Because of the way the lending programs

were structured, many loans were forgivable, and therefore effectively functioned as

grants or direct payments.

1

For, example, early figures show that 99 percent of the

value of SBA’s Paycheck Protection Program loans have been forgiven.

2

Additionally,

although the Medicare Accelerated or Advanced Payment program technically

distributed loans against future reimbursable healthcare services, the $2 billion spent

under this program would not have to be repaid unless the funding exceeded the

amount of services that were ultimately provided.

3

These findings include all identifiable pandemic relief grants and loans that flowed to

portfolio companies backed by the biggest American private equity firms. The included

firms all had more than $5 billion in assets under management (AUM) as of August

PUBLIC MONEY FOR PRIVATE EQUITY

10

2020, according to Pitchbook. By restricting the sample to this minimum AUM

threshold, this analysis focuses squarely on those private equity firms that had the

internal resources to assist their portfolio companies in managing the fallout from the

pandemic. This analysis uses multiple data sets and independently verified research

to make as careful a list of portfolio firms and assets during 2020 as is possible given

the opacity of the private equity industry.

The portfolio companies were identified using private equity firm websites and

databases that track private equity ownership (Pitchbook, Preqin, and Orbis). The

pandemic relief data came from the Project on Government Oversight’s COVID Relief

Spending Tracker. The companies that received CARES Act funding were not required

to identify their parent companies or investors in many cases used corporate names

based on historical state incorporation. This analysis made every effort to accurately

connect these recipients to their parent private equity-backed portfolio companies

based on their names and locations and connection to private equity-backed

companies, but in some cases the similarity of names may incidentally include firms

that are not backed by private equity. Based on quality control checks, we estimate

this potential error is quite small, affecting less than 1% of the recipients identified in

the dataset. (See Methodology at page 41 for a more detailed explanation of this

matching process.)

Per Table 1, over $4 billion (76 percent of the total pandemic relief to the industry)

went to portfolio companies owned by just 10 private equity firms. Leading the way,

companies backed by the private equity firm Apollo Global Management (Apollo)

received $1.4 billion. The portfolios of Cerberus Capital Management (Cerberus)

received $883 million and Welsh, Carson, Anderson & Stowe received $436 million.

A. Private Equity-Backed Healthcare Companies Received

$3.9 Billion.

Private equity has surged into the healthcare sector over the past two decades with

the number of healthcare leveraged buyouts in North America doubling from 80 deals

in 2014 to a record of 159 deals in 2019.

4

Private equity firms now own healthcare

companies of every kind, including hospitals, clinics, ambulances, nursing homes,

physician groups, and dentists’ offices, among others. The predatory strategies they

PANDEMIC RELIEF WENT TO FIRMS BACKED BY PRIVATE EQUITY TITANS

11

use — such as debt-financed leveraged buyouts, stripping real estate assets out of

acquired companies, and severe cost cutting strategies — imperil the viability of

healthcare companies and threaten patient health.

In the wake of the pandemic, 143 healthcare providers backed by the largest private

equity firms secured at least $3.9 billion in public relief funds. Most of the money came

through accelerated Medicare payments to fund future services ($2.0 billion), provider

relief grants ($1.6 billion), and small business loan programs ($221 million). As

described above, several of these programs had provisions for loan forgiveness, and

a significant portion of this aid does not need to be repaid and effectively functions as

grants or direct payments.

Unsurprisingly, most of this money went to chains that operate hospitals ($2.69billion

or 74 percent of the healthcare support in this study). But funding also flowed to home

health companies ($231 million or 6 percent), physician groups ($194 million or 5

percent), and ambulance and air ambulance companies ($96 million or 2 percent).

More than 98 percent of the public support went to portfolio companies held by just

10 private equity firms (see Table 2). Apollo, alone, captured 35 percent of healthcare

pandemic relief uncovered in this analysis, primarily because of the $1.4 billion

received by its LifePoint hospital chain. Cerberus’ only healthcare portfolio company

that received support, the Steward Health Care hospital chain, received 20 percent of

all healthcare money while Leonard Green’s healthcare portfolio companies received

$389 million, most of which went to its hospital chain Prospect Medical Group ($336

million) and Aspen Dental ($21 million).

Despite the public health emergency, many of private equity’s practices that threaten

communities and patients continued unabated even as their portfolio companies

received billions of dollars in public money. Private equity’s playbook of raising prices

and cutting costs is often antithetical to providing quality and accessible healthcare.

Before the pandemic, private equity hospital chain acquisitions led to record high

prices and declining staffing.

5

Despite the public health emergency, many of private equity’s practices that threaten

communities and patients continued unabated even as their portfolio companies

received billions of dollars in public money. Private equity’s playbook of raising prices

and cutting costs is often antithetical to providing quality and accessible healthcare.

Before the pandemic, private equity hospital chain acquisitions led to record high

prices and declining staffing.

6

PUBLIC MONEY FOR PRIVATE EQUITY

12

TABLE 2: PANDEMIC RELIEF TO HEALTHCARE COMPANIES OF TOP 10

PRIVATE EQUITY FIRMS

Private Equity Firm

No. Awards

Pandemic Relief ($M)

Apollo

292

$1,405.0

Cerberus

70

$776.1

Welsh, Carson, Anderson & Stowe

309

$436.3

TPG Capital

268

$401.3

Leonard Green & Partners

169

$389.5

Kohlberg Kravis Roberts

407

$178.9

Ares Capital

161

$151.2

Bain Capital

142

$141.6

American Securities

111

$109.5

Levine Leichtman Capital Partners

133

$57.2

Source: POGO Database

During the pandemic, one private equity-owned chain proposed consolidating

hospitals as a cost-cutting measure — and another threatened to close a hospital

unless it received public support. Leonard Green’s Prospect Medical proposed

merging two facilities in Connecticut in late 2020, which would have essentially

eliminated a full-service rural community hospital and turned it into a remote

emergency room.

7

Cerberus’ Steward Health Care effectively held the community of Easton,

Pennsylvania, hostage during the early days of the pandemic by threatening to close

its Easton Hospital if it did not receive pandemic relief. Steward acquired Easton as

part of an eight-hospital leveraged buyout, loading the operations with debt and

higher costs to pay rent on hospitals they used to own.

8

In late March 2020, at the

height of the pandemic, Steward sent a letter to the Pennsylvania governor

threatening to close the hospital within days if it did not receive a $40 million public

PANDEMIC RELIEF WENT TO FIRMS BACKED BY PRIVATE EQUITY TITANS

13

bailout.

9

Pennsylvania paid $8 million to keep the hospital open for four weeks.

10

Steward received $3.1 million for Easton among the $776 million in federal pandemic

relief that flowed to the chain. In July 2020, the non-profit St. Luke’s University Health

Network signed a $15 million promissory note to absorb Easton into its network.

11

Public support flowed to private equity backed companies behind epidemic

of surprise medical billing

The private equity-owned companies that profit from the practice of surprise medical

billing received generous public support even as they continued to gouge patients

during the pandemic. Surprise medical billing — charging patients out-of-network fees

for services like ambulance rides, emergency room visits, or x-rays at in-network

hospitals or clinics — enables private equity-owned healthcare companies to increase

prices, extract more money from patients, and increase their own revenues. In cases

of surprise billing, unknowing patients are treated by doctors who are not network

hospital employees but, rather, employees of third-party staffing services that

contract with the hospital. These staffing services charge outrageously for the care

doctors provide, leaving patients to cover the out of network bill.

Several of the most infamous culprits behind these practices received significant

amounts of public pandemic relief money.

12

The two largest physician staffing firms

received nearly $65 million in pandemic relief: KKR-owned Envision Healthcare

received $61.8 million and Blackstone-owned TeamHealth received $2.8 million. The

rates these staffing services charge can be far higher than ordinary prices, and

because they are out-of-network, patients bear the brunt of these sky-high bills.

Private equity-owned ambulances and air ambulance companies have also sent prices

skyrocketing, often through the use of surprise bills. Patients have no choice about

which ambulance transports them to the hospital, so they are especially vulnerable to

surprise ambulance bills. Before 2000, ambulance services were primarily furnished

by public emergency services and non-profit hospitals (especially for air ambulances).

But the private equity industry rolled up the ambulance industry in a series of

leveraged buyouts. By 2017, nearly three-fourths of air ambulances were provided by

three for-profit companies and two were owned by private equity: American Securities’

Air Methods and KKR’s Global Medical Response.

13

Costs of air ambulance rides have

skyrocketed. The Government Accountability Office found that from 2010 to 2014, the

median price of an air ambulance ride increased 76 percent, about nine times faster

than inflation.

14

In 2020, the New York Times reported that prices continued to rise

about 15 percent a year after 2015.

15

PUBLIC MONEY FOR PRIVATE EQUITY

14

Air Methods received $59 million in pandemic relief funding while Global Medical

Response received $36 million. During the pandemic, an intubated 60-year old woman

suffering life threatening coronavirus symptoms in Pennsylvania was airlifted by Air

Methods from one hospital to another with better emergency resources.

16

The patient

was charged over $52,000 for the air transport and initially her insurance offered to

pay little or nothing. After the state insurance commission contacted the insurer, her

bill was resolved.

17

Box A: Private equity-backed energy companies with histories of

violations received millions

Private equity-backed energy companies collected more than $154 million from

pandemic lending programs, drawing largely from the PPP and the Main Street

Lending Program. Notably, companies with histories of environmental and safety

violations were not prohibited from receiving support. Private-equity backed

companies with long lists of violations received millions, despite public accusations

of cutting corners at the expense of workers and the public. Ramaco Resources, a

mining company owned by Energy Capital partners, has also racked up a long list of

worker safety violations, including $43,000 worth of fines since 2020.

18

Despite

receiving multiple citations by federal mine safety regulators, the company received

an $8.4 million PPP loan, placing the company in the top 0.1 percent of PPP

recipients in 2020.

19

More than 80 percent of ground ambulance trips also result in surprise medical bills

that can run from $2,000 to $4,000.

20

While the bills are lower than for helicopter trips,

ground ambulance trips are far more common and, nationally, patients pay $129

million annually in surprise ground ambulance bills, according to a 2020 Health Affairs

study.

21

These bills continued during the pandemic. A Consumer Reports writer was

charged an $1,800 out-of-network surprise bill for an ambulance ride when sedated

for his coronavirus treatment.

22

Millions of people receive surprise medical bills annually and these private-equity

imposed bills have worsened the widespread and significant burden of medical debt,

which contributes to two-thirds of household bankruptcies.

23

Some private equity

firms aggressively pursue this medical debt in court. One TeamHealth subsidiary filed

PANDEMIC RELIEF WENT TO FIRMS BACKED BY PRIVATE EQUITY TITANS

15

more than 4,800 bill collection lawsuits against patients in a single Tennessee county

between 2017 and 2019.

24

For years, the private equity industry staved off any congressional efforts to address

surprise medical billing. In 2019, amid rising public outrage over surprise billing,

Congress began contemplating legislation that would rein in abusive bills for out-of-

network care. In response, an anonymous group called Doctor Patient Unity launched

fear-mongering advertisements nationwide warning of horrors if hospital bills were

subject to “government rate setting.” In one commercial, a patient arrived via

ambulance to a hospital only to find the lights turned off and the hospital empty.

25

TeamHealth and Envision Healthcare were the largest funders of Doctor Patient Unity,

which spent over $50 million in lobbying and advertising to derail surprise billing

legislation in 2019.

26

In 2020, Doctor Patient Unity invoked the coronavirus to bolster its case against

surprise billing legislation. The private equity-backed front group ran ads implying that

efforts to curb surprise medical billing would compromise coronavirus treatment, with

one stating “During this crisis, Congress needs to ensure they have the resources they

need to continue saving lives.”

27

The ads omitted the fact that staffing firms including

TeamHealth and Envision quickly cut emergency room doctors’ hours and pay soon

after the pandemic struck.

28

When some CARES Act provisions were extended in December 2020, Congress passed

a measure to address surprise billing. But the legislative fix left gaps and loopholes

that may allow private equity-backed companies to charge higher bills. The provisions

did not ban higher out-of-network charges; instead, billing disputes will go to

arbitration, in what Bloomberg called a “win for the [private equity] healthcare

companies.”

29

The legislative changes should provide patients with some insulation

from these charges, but do not seem to fully solve the problem. It did cover air

ambulances, but ground ambulances were totally excluded from the legislative fix and

can still charge surprise bills.

30

In addition, none of the protections are expected to

take effect before 2022,

31

allowing private equity-backed surprise billing to continue

for at least another year.

32

PUBLIC MONEY FOR PRIVATE EQUITY

16

B. Private Equity Captured $1.2 billion in Funds Earmarked

for Small Businesses

More than 14,000 private equity-backed entities — restaurant chains, service

franchises, medical offices, and others — received more than $1.2 billion under the

Small Business Administration (SBA) programs that ostensibly were created to keep

independent and small businesses afloat during the pandemic. Generally, SBA loan

programs exclude companies owned by private equity firms with a controlling,

majority stake. But special statutory carve-outs and lax enforcement allowed private

equity-backed companies to freely access the CARES Act’s new Paycheck Protection

Program (PPP) and CARES Act funding through the SBA’s existing Economic Injury

Disaster Loan (EIDL) programs intended to shore up independent small businesses.

Even though the private equity firms in this analysis collectively had $908 billion in dry

powder, their portfolio companies still qualified for assistance under SBA loan

programs.

These SBA loans provided immense financial benefit to private equity-backed

companies. The PPP loans were forgivable if the recipients used the funds to keep

workers employed or pay essential expenses like rent or utilities, and verification of

these conditions has been slight.

33

Yet even if recipients did not qualify for loan

forgiveness, the loans were extremely attractive for larger firms that typically borrow

in the private markets; PPP interest rates were only 1 percent, which is less than one-

fifth the interest rate that borrowers were paying before the pandemic.

34

Even under

the conservative assumption that none of the loans in this analysis were forgiven, the

cheaper loan rates would represent a $128 million savings in interest payments.

35

Small Business Administration programs are intended to provide support for small

and independent businesses that are typically governed by rules that limit the size of

recipients, and specify that they should not be owned or controlled by large

companies or private equity investors through the affiliation rules.

36

The affiliation

rules apply to the existing EIDL program and the PPP. These rules were designed to

limit aid to companies that lacked access to private market credit and capital; private

equity firms that were flush with cash should be able to provide financial support to

their portfolio companies without outside help.

37

Private equity investments that were

not a controlling, majority stake in companies did not, however, run afoul of the

affiliation rules. Businesses also had to “certify in good faith that their PPP loan was

PANDEMIC RELIEF WENT TO FIRMS BACKED BY PRIVATE EQUITY TITANS

17

necessary” and whether they could “access other sources of liquidity sufficient to

support their ongoing operations,” which was intended to preclude affiliates of large

companies from receiving support, according to the Treasury Department.

38

The business 500-worker size limits apply to the affiliation rules, so that total

combined employees of the private equity firm and the portfolio company applying

for an SBA loan were required to be below the 500-employee size limit.

39

Most private

equity firms do not advertise the number of employees, but publicly traded private

equity firms like Apollo, Blackstone, Carlyle and KKR all have more than 500

employees, meaning that all their portfolio companies should have been ineligible for

any SBA loans under this criteria.

40

But exceptions to the CARES Act allowed private equity-backed companies to avoid the

SBA size and affiliation requirements. The affiliation rules were waived for restaurants,

hotels, and other franchises.

41

This allowed a host of private equity-backed companies

to access the program. For example, Roark Capital-owned franchises Massage Envy

and Anytime Fitness each received SBA loans worth $8.1 million; Blackstone-owned

Motel 6 received $6.3 million; and 3G Capital-backed Burger King received more than

$9.3 million.

Other private equity-backed companies that received money may in fact have been

ineligible for the PPP because they were wholly owned by large private equity firms

and did not meet any of the statutory hospitality or franchise exemptions. It appears

that neither the SBA nor the banks adequately ensured that applicants did not run

afoul of the affiliation and size rules of the program.

Some portfolio companies lobbied for access to the program and may have urged

their individual stores or locations to apply for loans. Aspen Dental (owned by Leonard

Green, American Securities, and Ares) helped its locations successfully apply for PPP

loans.

42

The Roark Capital-owned Inspire Brands which holds many of Roark’s

restaurant franchises, stated that the SBA programs were “designed to help

independently owned and operated restaurants, whether or not they are affiliated

with a broader franchise system.”

43

PUBLIC MONEY FOR PRIVATE EQUITY

18

TABLE 3: 10 LARGEST PRIVATE EQUITY FIRM BENEFICIARIES OF

SMALL BUSINESS LOANS TO PORTFOLIO COMPANIES

Private Equity Firm

No. SBA Loans

SBA Funding ($M)

Roark Capital Group

7,523

$180.4

Riverside Company

188

$51.6

Leonard Green & Partners

171

$49.2

H.I.G. Capital

56

$47.9

Levine Leichtman Capital Partners

600

$46.0

Ares Capital

93

$44.3

Invus Group

9

$36.5

L Catterton

17

$32.4

Blackstone Group

910

$31.5

Harvest Partners

1,160

$31.0

Top 10 Total

10,727

$550.8

Source: POGO Database

The ten private equity firms with portfolio companies receiving the most SBA support

in this analysis captured more than one-third of the funding through the program to

private equity-owned or controlled companies that we identified ($550 million, see

Table 3).

Private equity backed companies capture funds that should have supported

small businesses, especially those owned by women and people of color

The volume of lending to private equity-backed companies effectively made it harder

for genuinely small and independent businesses to access the pandemic loan

program. The $349 billion in initial PPP funding ran out within weeks, largely driven by

big chains and larger companies getting access to a program meant for small

PANDEMIC RELIEF WENT TO FIRMS BACKED BY PRIVATE EQUITY TITANS

19

businesses.

44

Many smaller businesses were deterred from applying because they

lacked existing banking relationships the program favored, had concerns about the

complexity of the application process, were worried about repayment, or simply

believed that they would not get approved for the program.

45

Even when the program

received a new round of funding in December 2020, more than 90 percent of PPP

lending went to companies that had already received loans from the earlier CARES

Act funding.

46

The impact was especially pronounced for small businesses owned by people of color

and women, which were more vulnerable during the pandemic. According to reporting

by the Associated Press, companies owned by people of color “were at the end of the

line in the government’s coronavirus relief program as many struggled to find banks

that would accept their applications or were disadvantaged by the terms of the

program.”

47

In the first months of the pandemic, the number of businesses owned by

people of color and women plummeted far faster than those owned by white men.

48

Yet a Goldman Sachs survey found that Black-owned businesses were less likely to

apply and more likely to get rejected for PPP loans.

49

Private equity fast food chains gobbled up small business loans

Restaurant chains captured over one-sixth (18 percent) of the small business loans

that went to private equity portfolio companies. Private equity firms have invested

heavily in restaurants including fast food, fast casual, and even higher-end fine dining

establishments, buying nearly 850 chains or locations from 2010 to 2017, more than

100 every year.

50

Many private equity-backed fast-food chains flourished during the pandemic.

51

The

CEO of Oak Hill Capital-owned Checkers/Rally’s chain claimed the chain experienced

“pandemic tailwinds” that gave the chain “an extremely good year.”

52

Other

restaurants were not so lucky. Nearly 30 percent of restaurants — most of which are

independent — are expected to close permanently because of the pandemic and over

110,000 were already out of business by October 2020.

53

Although firms were

supposed to certify that they needed the small business loans, more than 5,800 SBA

loans worth over $224 million were awarded to private equity-backed restaurants.

PUBLIC MONEY FOR PRIVATE EQUITY

20

TABLE 4: TOP 10 PRIVATE EQUITY-BACKED RESTAURANT CHAINS THAT

RECEIVED SBA LOANS

Chain

Private Equity Firm

No. SBA

Loans

SBA Loans

($M)

Sonic

Roark

707

$53.1

Dunkin’

Roark

2,248

$27.3

Mod Super-Fast Pizza

Clayton, Dubilier & Rice

3

$15.5

Zoe’s Kitchen

The Invus Group

2

$10.0

Torchy's Tacos

General Atlantic

1

$10.0

Sbarro

Apollo

15

$9.9

Hopdoddy Burger Bar

L Catterton

1

$9.5

Burger King

3G Capital

205

$9.4

Tastes On The Fly

H.I.G. Capital

5

$8.7

Jimmy John’s

Roark

500

$8.4

Top 10 Total

3,687

$161.8

Source: POGO Database

More than half the small business loans to private equity-backed restaurants went to

Roark Capital. Roark’s portfolio of restaurants including Dunkin’ Donuts, Sonic, Arby’s,

Jimmy John’s, Hardees and Buffalo Wild Wings received 4,447 small business loans

worth $115 million. More than two-thirds of all restaurant support ($161 million) went

to the 10 largest restaurant recipients including Sonic, Torchy’s Tacos, and Burger King

(see Table 4).

PANDEMIC RELIEF WENT TO FIRMS BACKED BY PRIVATE EQUITY TITANS

21

C. Private Equity’s Lobbying Efforts Helped Secure Access

to Public Funds

Part of the success private equity-backed portfolio companies have enjoyed in

accessing public funding can be attributed to the lobbying efforts of their parent firms.

Private equity firms have long been among the major players on K Street, spending

tens of millions every year lobbying the federal government. In most cases, these

expenditures were ramped up as Congress began debating how to best respond to

the economic crisis caused by the pandemic.

This analysis shows that eighteen private equity firms and the industry’s primary trade

association spent almost $32 million on lobbying during 2020, including on pandemic

related issues, based on lobbying disclosures data from the Center for Responsive

Politics.

54

Federal rules do not require registrants to break down how much was spent

lobbying each issue, but Oak Hill Capital and Searchlight Capital Partners never

reported any lobbying expenditures before the pandemic, yet reported spending

$180,000 and $100,000 on lobbying in 2020, respectively. The only issue listed on their

disclosures was the CARES Act.

55

The five biggest spenders (Blackstone, Apollo, Carlyle, Cerberus, and Energy Capital

Partners) all spent more than $3 million each on lobbying during 2020 (See Table 5.

Apollo increased its spending on lobbying by 77 percent between 2019 and 2020;

Blackstone and Carlyle both increased their spending on lobbying by more than 50

percent. It appears this lobbying was a good investment. Apollo spent $4.4 million

lobbying during 2020 and its portfolio companies received $1.49 billion in pandemic

support; Cerberus spent $3.2 million lobbying and its portfolio companies received

over $883 million.

The industry lobbied both Congress and the Small Business Administration to

specifically allow all private equity-owned companies to be eligible for the PPP.

56

Leading many of the lobbying efforts was the major trade group representing the

industry, the American Investment Council, which spent over $2.2 million in 2020,

including $640,000 in the first quarter of 2020 in an attempt to shape the rollout of

the pandemic relief funds.

57

The Small Business Administration officials privately told

the private equity industry to use its own cash reserves instead of the PPP to support

their struggling portfolio companies.

58

Nonetheless, one private equity firm

threatened to fire workers unless it was given access to the small business loans,

PUBLIC MONEY FOR PRIVATE EQUITY

22

TABLE 5: TOP PRIVATE EQUITY LOBBYING EXPENDITURES 2019-2020

Private Equity Firm

2019

Lobbying

Spending

(All

Issues)

2020

Lobbying

Spending

(All

Issues)

2019 to

2020

Lobbying

Spending

Increase

CARES Act

Money

Received by

Portfolio

Companies

The Blackstone Group

$3.6

$5.6

55%

$34.3

Apollo

$2.4

$4.3

77%

$1,489.3

The Carlyle Group

$2.2

$3.3

52%

$131.0

Cerberus

$2.3

$3.1

33%

$883.3

Energy Capital Partners

$5.9

$3.0

-49%

$9.4

Kohlberg Kravis Roberts

$1.6

$2.4

46%

$198.4

American Investment

Council (trade association

for the private equity

industry)

$2.0

$2.1

5%

N/A

Morgan Stanley Energy

Partners / Morgan Stanley

Capital Partners

$2.6

$2.0

-21%

$0.5

TPG Capital

$1.5

$1.5

-1%

$428.6

Ares Capital

$1.0

$1.4

38%

$164.7

AEA Investors

$0.9

$1.0

6%

$2.9

Total

$26.5

$30.2

14%

$3,343.4

Source: All figures are in millions USD. Center for Responsive Politics and POGO Databases

PANDEMIC RELIEF WENT TO FIRMS BACKED BY PRIVATE EQUITY TITANS

23

telling the Financial Times that “if the government wants to limit [PPP] funding for

companies we own just to punish the private equity industry, we will have to take

drastic measures…That means cutting costs aggressively and restructuring.”

59

Notably, some pandemic relief loans may have essentially subsidized anti-worker

lobbying efforts. In 2021, Roark Capital’s Inspire Brands (the operator of restaurant

franchises like Sonic and Arby’s) told its workers and franchises that it had successfully

lobbied against measures to raise wages from being included in the Biden

administration’s pandemic stimulus legislation and against legislation to protect

workers trying to form unions.

60

The Inspire memo stated clearly “We were successful

in our advocacy efforts to remove the Raise the Wage Act, which would have increased

the federal minimum wage to $15 and eliminated the tip credit.”

61

PUBLIC MONEY FOR PRIVATE EQUITY

24

3. Private Equity Was Positioned to Thrive During the

Pandemic Without Public Support

The private equity industry was sitting on a record-breaking

mountain of cash headed into the pandemic — nearly $1.5 trillion

at the end of 2019.

Private equity firms use money from both wealthy individuals and institutional

investors like pension funds, university endowments, and sovereign wealth funds to

take over companies as investment vehicles. Purportedly, these firms deliver

management expertise and needed financing to struggling or undervalued companies

in order to improve their performance. Then they either sell these portfolio companies

or launch them onto the stock exchange through initial public offerings. In reality, the

private equity industry deploys predatory practices and exploits regulatory blind spots

to shift value and profits from the real economy to Wall Street firms and executives.

The private equity industry’s predatory practices generate outsized profits for

investors but can imperil portfolio companies and workers. The industry’s tactics

include aggressive cost cutting, imposing high debt loads from leveraged buyouts,

wringing out value in fees and dividends, and stripping out valuable real estate and

other assets from portfolio companies. The absence of binding conditions in the

CARES Act allowed the unabated continuation of these practices during the pandemic.

Private equity firms have taken over a larger and larger share of the economy. In the

decade between 2010 and 2019, the number of private equity leveraged buyouts

doubled, with the value of the deals surging 175 percent from $2.7 billion in 2010 to

$5.5 billion in 2019 (see Figure 2).

62

Although private equity takeovers declined in 2020,

the decline was far smaller than immediately after the 2008 financial crisis, which saw

a 31 percent decline in the number of deals from 2008 to 2009 compared to a 3

percent decline from 2019 to 2020. The private equity industry had a substantial grip

on the real economy on the cusp of the pandemic. In May 2020, U.S. private equity

firms controlled 8,000 companies amounting to 5 percent of the economy and

workforce.

63

PANDEMIC RELIEF WENT TO FIRMS BACKED BY PRIVATE EQUITY TITANS

25

Private equity takeovers often overburden portfolio companies with so much debt and

fees that the companies slide into bankruptcy. The target companies — not the private

equity investors — are responsible for repaying the debt from leveraged buyouts and

dividend recapitalizations. Highly leveraged buyouts mean that the private equity

firms and executives can generate more profits from successful investments, but the

high level of debt the acquired companies are saddled with can cause portfolio

companies to collapse. A 2019 California Polytechnic State University study found that

20 percent of companies taken over by private equity went into bankruptcy — a rate

ten times higher than the non-private equity-backed companies.

64

Private equity-

driven bankruptcies have become especially common in the retail industry. From 2015

to 2019, all before the pandemic, nearly two-thirds (62.5 percent) of retail companies

that went into bankruptcy were owned by private equity.

65

Although their portfolio companies are more vulnerable to bankruptcy, private equity

firms had ample financial resources to support them during the pandemic yet still

accessed public support that could have gone to those with fewer reserves. The

private equity industry was sitting on a record-breaking mountain of cash headed into

the pandemic — nearly $1.5 trillion at the end of 2019.

66

This huge amount of cash on

hand (including money already committed from outside investors), known as dry

powder, was available to take over more portfolio companies or shore up struggling

ones during the pandemic. The 113 private equity firms analyzed in this study had

$908 billion in dry powder during 2020.

PUBLIC MONEY FOR PRIVATE EQUITY

26

Using public money to stabilize their portfolio companies during the pandemic,

allowed private equity firms to hoard their dry powder to pursue new investments and

extend their reach even further, taking advantage of other distressed firms. Some

private equity firms even asked their portfolio companies to use their own credit lines

— e.g., take on even more debt — to pump cash into struggling businesses.

67

The private equity industry contends that dry powder reserves are not always

available to support portfolio companies — older private equity funds may have

exhausted their reserves and newer funds may be dedicated to new leveraged

buyouts.

68

But the reality is that most of the dry powder is from funds raised in the

past few years, and these funds could be used to shore up older investments (known

as cross-fund investments).

69

And many older funds do have sufficient capital to

backstop struggling portfolio companies. For example, about one-fifth of Blackstone’s

dry powder was in older funds that could “support companies on the defensive,”

according to one Blackstone advisor.

70

The private equity industry was more interested in the greater potential for profits

from new leveraged buyouts and takeovers than reinvesting dry power in struggling

companies, even when there were funds available.

71

The industry has touted the

golden opportunities to capitalize on the pandemic recession and eventual recovery.

Blackstone chief executive Steven Schwarzman said his firm was “looking aggressively”

for “very significant investments” to deploy its dry powder.

72

Apollo’s Leon Black stated

that the pandemic presented a “massive” investment opportunity for private equity

firms.

73

A Bain & Co. presentation to investors cheered that “during and post this crisis,

private equity firms will be presented with unique opportunities to invest — important

to be ready to act.”

74

One Goldman Sachs associate said that “corporate raiders and

private equity firms are already sharpening their knives because prices are obviously

very low right now.”

75

This mirrors the vulture capitalist strategy the private equity industry followed after

the 2008 financial crisis: Use its mountain of cash to buy distressed companies and

make a killing.

76

It appears the public pandemic support for private equity portfolio

companies may have facilitated the ability of the industry to go on another takeover

tear. In 2020, one KKR official told investors that the firm had “invested into the

recovery” after the 2008 financial crisis and was eager to profit on the country’s

recovery from the pandemic.

77

PANDEMIC RELIEF WENT TO FIRMS BACKED BY PRIVATE EQUITY TITANS

27

4. Private Equity’s Predatory Practices Have Been

Essentially Supported by Public Money

The CARES Act provided about $2 trillion in support during the pandemic,

78

but the

legislation provided few requirements to ensure public funding was used to support

workers and business operations, rather than enrich investors or executives.

Advocates and some members of Congress were only minimally successful in

including binding conditions on the receipt of public money that would direct funding

to workers, prevent the extraction of dividends and fees, or prohibit the acquisition of

additional companies.

Private equity firms that owned or backed companies receiving public money were

largely free to continue their predatory practices of extracting value through

dividends, cutting costs (including layoffs), and pursuing more takeovers. The result

was that the public support that flowed to the private equity portfolio companies

effectively subsidized these private equity practices that could enrich investors, harm

workers, and undermine the viability of portfolio companies during the pandemic-

driven economic slump.

The largely unconditional public financial support that flowed to private equity-backed

companies poses unique risks because of the industry’s extractive business model.

Public support could easily be diverted from portfolio companies to the private equity

firms. The general lack of guardrails to protect jobs and workers or prevent the

diversion of public funds to investors meant that there were no limits on private equity

firms’ ability to siphon away pandemic relief expenditures.

Collectively the industry’s predatory practices generate outsized revenues and profits

that are shifted from the real economy to the private equity firms and can put target

companies at higher risk of failure. As Vanity Fair observed, “the fear, of course, is that

private equity will do what private equity does best, which is pocket the money

themselves rather than devoting it to the businesses they’ve invested in.”

79

There are

five common private equity financial engineering schemes that extract value from

portfolio companies: cost cutting that harms workers, leveraged buyout acquisitions,

extracting debt-funded dividends, charging exorbitant fees, and exploiting tax

loopholes.

PUBLIC MONEY FOR PRIVATE EQUITY

28

A. Private Equity-backed Companies Accepted Public

Support but Shed Workers

The CARES Act had few binding requirements that companies receiving aid keep

workers on payroll or maintain critical benefits like healthcare or sick leave during the

pandemic. A common tactic used by private equity to make money off their

acquisitions is to impose severe cost cutting on their portfolio companies. According

to Businessweek, this cost-cutting “inevitably means job cuts;” layoffs and/or downsizing

help lower expenses and increase revenues.

80

Many CARES Act provisions lacked any job retention requirements (like the healthcare

grants), others had imperfect provisions that did not require recipients to keep

workers on the payroll. Only the aviation payroll program had binding measures that

directed the funding to safeguarding workers. The Treasury programs that provided

loans to businesses only required a limited subset of companies (airlines, air cargo,

and defense) to maintain their workforce “to the extent practicable.”

81

The airline

program was largely successful in terms of job retention (but thousands of workers

were furloughed when the program expired for a period in late 2020

82

). Three air

transport companies owned by the largest private equity firms took public funding

that was supposed to protect workers’ jobs and nonetheless laid off workers (see Box

B). Other programs administered by the Treasury Department did not have

meaningful requirements to protect workers, allowing some recipients to skirt

oversight.

83

Although the Federal Reserve’s Main Street Lending Program instructed

borrowers to make “commercially reasonable efforts to retain employees,” companies

that fired or furloughed workers were still eligible for the loans.

84

For the more than 73 percent of the public funds that flowed to the largest private

equity-owned and -backed companies went to the healthcare industry, there were no

requirements that recipients keep workers on the job even though healthcare workers

were essential during the public health crisis. While some of the public money was

used to provide Coronavirus treatments, much replaced lost revenues caused by the

sharp decline in non-urgent, elective health services during the pandemic.

85

Companies that received public funds were able to keep facilities afloat, but did not

need to maintain their workforce or to direct the public funding to maintaining

previous operational levels.

PANDEMIC RELIEF WENT TO FIRMS BACKED BY PRIVATE EQUITY TITANS

29

BOX B: Private equity-backed airlines fired workers in apparent violation of the

aviation payroll protection requirements

Some private equity-backed air transport companies received funding under a

program designed to protect aviation workers but nonetheless furloughed workers.

The CARES Act aviation worker payroll protection program contained the only

binding protections ensuring relief recipients retained workers and prohibited

beneficiaries from shifting public funds to executives or investors.

86

The air transport

companies that received CARES Act support were required to maintain 90 percent of

their workforce through the end of September 2020, to use the funding exclusively

for payroll support, to protect existing agreements with unionized workers, and to

prohibit airlines from furloughing workers or cutting pay or benefits.

87

The Air Line

Pilots Association reported that the program was quite successful and estimated that

83 percent of airline and air cargo workers still were working for the industry a year

later and the worst impacts of the pandemic on the industry had been successfully

mitigated.

88

These aviation-specific conditions applied to the private equity-owned air transport

companies that received nearly $341 million in public support. Nonetheless, some

appear to have reduced payrolls even after they agreed to take aviation payroll

support. Three air transport companies that the House Select Subcommittee on the

Coronavirus Crisis found had laid off workers after they signed agreements under

the aviation payroll program were backed by private equity firms. Carlyle’s

PrimeFlight and Nordam Group (nearly $120 million in public support) as well as JLL

Partners-owned Aviation Technical Services (ATS) (nearly $40 million) laid off workers

after they applied for the aviation payroll program.

89

Two private equity owned aviation companies laid off workers before the legislation

was finalized, and then applied for and received money. PrimeFlight and ATS laid off

workers as the CARES Act was being finalized,

90

which sidestepped the requirement

to keep workers in their jobs. ATS slashed nearly one-fifth of its jobs before it

finalized its aviation payroll support agreement and implied that it would be forced

to fire more workers without federal support.

91

PUBLIC MONEY FOR PRIVATE EQUITY

30

Some healthcare companies that received public support furloughed or reduced the

hours for medical workers during the pandemic. In April 2020, Apollo-owned LifePoint

Health hospitals began laying off workers, typically announcing that furloughed

workers would receive 25 percent of their pay and full benefits. The chain’s hospitals

offered nearly identical quotations: “these are necessary measures to ensure we are

maximizing our resources and supporting our teams on the front lines of battling

COVID-19.”

92

The LifePoint chain received over $1.4 billion in federal assistance even

as it furloughed workers. While LifePoint’s workers struggled during the pandemic,

Apollo and its investors had already realized profits of more than $800 million as of

March 2020.

93

Other companies let healthcare workers go during the pandemic while receiving

public support. KKR-owned Envision Healthcare received $61 million and New

Mountain Capital-owned Alteon Health received over $3 million, but both reduced

medical staff hours, and Alteon furloughed staff and reduced benefits, according to

ProPublica.

94

Blackstone-owned TeamHealth received $2.8 million in public support

but apparently fired one of its doctors for raising concerns about worker safety during

the pandemic. A Seattle TeamHealth emergency room physician warned early in the

pandemic that the hospital was not taking basic safety precautions, such as separating

coronavirus patients from other patients or adequately protecting workers from

exposure.

95

The doctor, who was warned that the hospital was upset about

statements he had made on Facebook, was fired at the end of March 2020.

96

B. Private Equity Firms Pursued Hundreds of Takeovers

During the Pandemic

Private equity firms continued a takeover tear during the pandemic even as their

portfolio companies received public funding. The CARES Act had no provisions that

would prevent the recipients of public money or their investors from acquiring other

companies during the economic downturn. Federal support could subsidize or

encourage consolidation by making it easier for private equity firms to use resources

to purchase rival or complementary businesses, as happened in the aftermath of the

2008 financial crisis.

97

The ten private equity firms whose portfolio companies received

the most pandemic relief acquired 230 companies in leveraged buyouts with a

disclosed value of over $45 billion from March to December 2020.

PANDEMIC RELIEF WENT TO FIRMS BACKED BY PRIVATE EQUITY TITANS

31

Private equity firms are relentless acquirers, purchasing companies through leveraged

buyouts that force the target companies to take on debt to finance their own takeover.

The huge debt loads imposed on target companies to finance these buyouts are the

“core of the business” according to Businessweek.

98

The leverage can produce outsize

gains for private equity executives, while the portfolio company is responsible for

repaying the loans, creating a debt burden that requires it to divert revenues to pay it

back, and that can overwhelm its finances and lead to bankruptcy, costing workers

their jobs and economic security. The portfolio companies are forced to divert

revenues to service the debt loads. The CARES Act did not prevent recipients from

using public money to repay private equity-imposed debts, meaning funds could be

diverted from keeping workers on the job to those payments.

Public funds flowed to portfolio companies already struggling from

leveraged buyouts

Several private equity-owned companies that received pandemic relief have massive

leveraged buyout debt loads. Cerberus-owned Steward Health Care network of

hospitals received over $776 million in public support. The chain has struggled under

$1.3 billion in debt rooted in a 2010 leveraged buyout, compromising the quality of

care and its financial viability according to Bloomberg.

99

Cerberus sold the hospital

chain during the pandemic (and after much of the public support had been doled out),

but not before quadrupling its investment and pocketing $800 million in profits.

100

Most of the profits were not from successful hospital operations, but were from

Cerberus selling the hospital real estate to other investors, generating profits for

Cerberus but forcing the hospital to pay rent on facilities the chain previously owned,

known as a sale-leaseback.

Multiple portfolio companies that received CARES Act funding were teetering on the

brink of bankruptcy before the pandemic because of private equity-imposed debt

loads and financial engineering. For example, Apollo bought the Chuck E. Cheese's

restaurant chain in a 2014 $1.3 billion leveraged buyout that imposed a $925.9 million

debt burden on the company.

101

The kids-oriented restaurant chain was struggling

before the pandemic because its debt load constrained its ability to update its

business.

102

Nine Chuck E. Cheese restaurants received a combined $110,000 in CARES

Act funding before the chain slid into bankruptcy in June 2020 as the debt burden

made it impossible to cope with the pandemic’s impact on the chain’s business.

103

PUBLIC MONEY FOR PRIVATE EQUITY

32

Six Art Van Furniture stores received $298,000 in CARES Act funding, even though the

T.H. Lee Partners-owned retailer was already in bankruptcy by March 2020 as a result

of the $400 million in debt from its 2017 leveraged buyout.

104

In March 2020, before

the CARES Act was enacted, Art Van had closed all of its stores and laid off 4,500

workers and refused to repay workers for the money they deposited in their flexible

health savings accounts.

105

It took fired workers organizing and pressing T.H. Lee for

a year to get the company to establish a $2 million fund to provide about $1,200 each

to those who lost their jobs.

106

Public funds fuel private equity takeovers

The private equity firms that held portfolios that received the most in public money

were highly acquisitive after the CARES Act was enacted. The public support that went

to the portfolio companies provided more latitude for new acquisitions and could even

subsidize the debt used to finance these leveraged buyouts. The ten private equity

firms whose portfolio companies received the most CARES Act funding made 230

leveraged buyouts (LBOs) in the United States with a disclosed value of over $45 billion

from March 2020 to December 2020 (see Table 6).

107

The number of leveraged buyouts

stalled in the early months of the pandemic but rose steadily over the rest of the year,

exceeding 50 LBOs in December alone (see Figure 3).

PANDEMIC RELIEF WENT TO FIRMS BACKED BY PRIVATE EQUITY TITANS

33

Some private equity-backed companies that received pandemic relief subsequently

bought up more companies. Kindred Healthcare (owned by TPG Capital and Welsh,

Carson, Anderson & Stowe) received more than $240 million in public support. In the

summer of 2020, it announced the takeover of two behavioral health hospitals in

Dallas for an undisclosed sum.

108

Table 6: Leveraged Buyouts by Top 10 CARES Act Private

Equity Firms

Private Equity Firm

CARES Act

($M)

No. of LBOs*

LBO Value

($M)°

Apollo

$1,489.3

13

$9,353.0

Cerberus

$883.3

7

$250.0

Leonard Green & Partners

$419.3

36

$5,226.0

Welsh, Carson, Anderson & Stowe

$436.3

12

$700.0

TPG Capital

$428.6

24

$3,198.6

Roark Capital Group

$183.4

5

$10,310.0

KKR

$198.4

46

$8,808.1

Ares Capital

$164.8

16

$1,118.0

The Carlyle Group

$131.0

61

$6,123.2

Bain Capital

$142.0

20

$2,501.2

Top 10 Total

230

$45,116.0

Source: Pitchbook and POGO databases.

*

Number of LBOs includes 10 club deals where more than one firm

participated in the takeover, total reflects the number and value of the target LBOs.

°

LBO value reflects reported

values; 80 percent of the LBOs did not report deal value.

PUBLIC MONEY FOR PRIVATE EQUITY

34

North American Partners in Anesthesiology (owned by American Securities and

Leonard Green) received more than $15 million in pandemic relief before buying

American Anesthesiology in an estimated $250 million deal.

109

American

Anesthesiology had also received $13 million in funding before the takeover, meaning

the federal government supported both the acquirer and the target. Other leveraged

buyouts targeted companies that had been big recipients of CARES Act funds. For

example, Dunkin’ received $27 million in CARES Act support before Roark Capital

bought it in an $11.3 billion leveraged buyout in October 2020.

110

Levine Leichtman

Capital Partners bought the nearly 900-location Tropical Smoothie Café after it

received $6.6 million in small business loans during the pandemic.

111

And, the tear is not over. Apollo is aggressively pursuing more hospital acquisitions. In

March 2020, an Apollo partner said that pandemic was Apollo’s “time to shine.”

112

In

May 2020, the firm wrote to investors: “Independent hospital systems have greater

difficulty weathering prolonged periods of financial stress … A consolidation strategy

will provide meaningful upside for Apollo funds' investment.’’

113

In 2021, Apollo’s

LifePoint announced intended deals to buy Kindred Health’s network of about 190

rehabilitation facilities and reportedly was in serious discussions to buy Ardent Health

Services’ chain of 30 hospitals.

114

C. Private Equity Firms Took Dividends out of Companies

that Received Pandemic Relief

Private equity firms managed to extract debt-funded dividends from companies that

received public support. Private equity firms often require portfolio companies to

borrow more money to pay a dividend to the private equity firm, known as dividend

recapitalization.

115

This extraction delivers instant cash to the private equity firm but

adds to the portfolio companies’ debt loads and can contribute to bankruptcies.

116

Dividend recapitalizations actually increased during the pandemic, reaching a record

level of $6 billion in September 2020 alone.

117

The CARES Act had few prohibitions to keep private equity firms or other companies

from extracting dividends from companies that received public support. Most

programs had no statutory limitations on recipients paying dividends, with only the

airline workers program, the SBA’s Economic Injury Disaster Loan programs and the

Main Street Lending Program banning the practice (in the latter case, the Treasury

PANDEMIC RELIEF WENT TO FIRMS BACKED BY PRIVATE EQUITY TITANS