INFORMATION

RESELLERS

Consumer Privacy

Framework Needs to

Reflect Changes in

Technology and the

Marketplace

Report to the Chairman, Committee

on Commerce, Science, and

Transportation, U.S. Senate

September 2013

GAO-13-663

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-13-663, a report to the

Chairman, Committee on Commerce, Science,

and Transportation, U.S. Senate

September 2013

INFORMATION RESELLERS

Consumer Privacy Framework Needs to Reflect

Changes in Technology and the Marketplace

Why GAO Did This Study

In recent years, information resellers—

companies that collect and resell

information on individuals—

dramatically increased the collection

and sharing of personal data for

marketing purposes, raising privacy

concerns among some in Congress.

Recent growth in the use of social

media, mobile applications, and other

technologies intensified these

concerns. GAO was asked to examine

privacy issues and information

resellers. This report addresses (1)

privacy laws applicable to consumer

information held by resellers, (2) gaps

in the law that may exist, and (3) views

on approaches for improving consumer

data privacy.

To address these objectives, GAO

analyzed laws, studies, and other

documents, and interviewed

representatives of federal agencies,

the reseller and marketing industries,

consumer and privacy groups, and

others. GAO focused primarily on

consumer information used for

marketing purposes.

What GAO Recommends

Congress should consider

strengthening the consumer privacy

framework to reflect the effects of

changes in technology and the

increased market for consumer

information. Any changes should seek

to provide consumers with appropriate

privacy protections without unduly

inhibiting commerce and innovation.

The Department of Commerce agreed

that strengthened privacy protections

could better protect consumers and

support innovation.

What GAO Found

No overarching federal privacy law governs the collection and sale of personal

information among private-sector companies, including information resellers.

Instead, a variety of laws tailored to specific purposes, situations, or entities

governs the use, sharing, and protection of personal information. For example,

the Fair Credit Reporting Act limits the use and distribution of personal

information collected or used to help determine eligibility for such things as credit

or employment, but does not apply to information used for marketing. Other laws

apply specifically to health care providers, financial institutions, videotape service

providers, or to the online collection of information about children.

The current statutory framework for consumer privacy does not fully address new

technologies—such as the tracking of online behavior or mobile devices—and

the vastly increased marketplace for personal information, including the

proliferation of information sharing among third parties. With regard to data used

for marketing, no federal statute provides consumers the right to learn what

information is held about them and who holds it. In many circumstances,

consumers also do not have the legal right to control the collection or sharing

with third parties of sensitive personal information (such as their shopping habits

and health interests) for marketing purposes. As a result, although some industry

participants have stated that current privacy laws are adequate—particularly in

light of self-regulatory measures under way—GAO found that gaps exist in the

current statutory framework for privacy. And that the framework does not fully

reflect the Fair Information Practice Principles, widely accepted principles for

protecting the privacy and security of personal information that have served as a

basis for many of the privacy recommendations federal agencies have made.

Views differ on the approach that any new privacy legislation or regulation should

take. Some privacy advocates generally have argued that a comprehensive

overarching privacy law would provide greater consistency and address gaps in

law left by the current sector-specific approach. Other stakeholders have stated

that a comprehensive, one-size-fits-all approach to privacy would be burdensome

and inflexible. In addition, some privacy advocates have cited the need for

legislation that would provide consumers with greater ability to access, control

the use of, and correct information about them, particularly with respect to data

used for purposes other than those for which they originally were provided. At the

same time, industry representatives have asserted that restrictions on the

collection and use of personal data would impose compliance costs, inhibit

innovation and efficiency, and reduce consumer benefits, such as more relevant

advertising and beneficial products and services. Nonetheless, the rapid increase

in the amount and type of personal information that is collected and resold

warrants reconsideration of how well the current privacy framework protects

personal information. The challenge will be providing appropriate privacy

protections without unduly inhibiting the benefits to consumers, commerce, and

innovation that data sharing can accord.

View GAO-13-663. For more information,

contact Alicia Puente Cackley at (202) 512-

8678 or

Page i GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

Letter 1

Background 2

Several Laws Apply in Specific Circumstances to Consumer Data

That Resellers Hold 7

Existing Privacy Laws Have Limited Scope over Personal Data

Used for Marketing 16

Views Differ on Specific versus Comprehensive Approaches to

Privacy Law and on Consumer Interests 31

Conclusions 46

Matter for Congressional Consideration 46

Agency Comments 47

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 48

Appendix II Examples of Data Collected and Used by Information

Resellers 52

Appendix III Comments from the Department of Commerce 54

Appendix IV GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 56

Tables

Table 1: Fair Information Practice Principles 6

Table 2: Selected Examples of Consumer Data in Acxiom’s

Marketing Products, 2012 52

Table 3: Selected Examples of Marketing Lists Available from

Experian, 2012 53

Figures

Figure 1: Typical Flow of Consumer Data through Resellers to

Third-Party Users 3

Figure 2: Dates of Enactment of Key Federal Privacy Laws and the

Introduction of New Technologies 21

Contents

Page ii GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

Abbreviations

CFAA Computer Fraud and Abuse Act

COPPA Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act

ECPA Electronic Communications Privacy Act

EU European Union

FCRA Fair Credit Reporting Act

FIPPs Fair Information Practice Principles

FTC Federal Trade Commission

GLBA Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act

HIPAA Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

September 25, 2013

The Honorable John D. Rockefeller IV

Chairman

Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

United States Senate

Dear Mr. Chairman:

Some members of Congress and others have raised privacy concerns

about the collection and use of consumers’ personal information by

information resellers—companies with a primary line of business of

collecting, aggregating, and selling personal information to third parties. In

part, their concerns stem from consumers not always knowing the nature

and extent of the information collected about them and how it is used and

shared. The information reseller industry has grown significantly in recent

years, as has the amount of consumer information that these companies

assemble and distribute. Moreover, growing use of the Internet, social

media, and mobile applications has intensified privacy concerns because

these media greatly facilitate the ability to gather increasing amounts of

personal information, track online behavior, and monitor locations and

activities.

You asked us to review privacy issues related to consumer data

collected, used, and shared by information resellers. This report

examines (1) existing federal laws and regulations relating to the privacy

of consumer information held by information resellers, (2) any gaps that

may exist in this legal framework, and (3) views on approaches for

improving consumer data privacy. This report focuses primarily on privacy

issues related to consumer information used for marketing and for

individual reference services (also known as look-up or people-search

services); it does not focus on information used for other purposes, such

as fraud prevention and eligibility for credit or employment.

1

1

In 2006, we issued a report examining financial institutions’ use of information resellers,

which focused largely on consumer information used to make eligibility determinations for

credit, insurance, and employment, comply with certain legal requirements, and prevent

fraud. GAO, Personal Information: Key Federal Privacy Laws Do Not Require Information

Resellers to Safeguard All Sensitive Data,

GAO-06-674 (Washington, D.C.: June 26,

2006).

Page 2 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

To address the first and second objectives, we reviewed and analyzed

relevant federal laws, regulations, and enforcement actions, and selected

state laws. We interviewed representatives of federal agencies, trade

associations, consumer and privacy groups, and information resellers to

obtain their views on federal data privacy laws related to information

resellers, including the adequacy of consumers’ ability to access, correct,

opt out, or request deletion of information. To address the third objective,

we identified and reviewed approaches for improving consumer data

privacy through legislative, regulatory, or self-regulatory means that

federal entities—including the White House, Federal Trade Commission

(FTC), and Department of Commerce (Commerce)—or representatives of

industry, consumer, and privacy groups have advocated. We also

interviewed representatives of these entities and reviewed relevant

studies, congressional hearing records, position papers, public

comments, and other sources. Appendix I contains a more extensive

discussion of our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from August 2012 through

September 2013, in accordance with generally accepted government

auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the

audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable

basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We

believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Information resellers—sometimes also called data brokers, data

aggregators, or information solutions providers—offer several types of

products to customers that include retailers, advertisers, private

individuals, nonprofit organizations, and law enforcement and other

government agencies. Consumer reporting agencies—including the three

nationwide credit bureaus, Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion—provide

consumer reports that commonly are used to determine eligibility for

credit, employment, and insurance. Some resellers offer products that

help companies comply with legal requirements or identify, investigate,

and prevent fraudulent transactions (for example, by enabling

confirmation of a customer’s identity). Some information resellers, such

as Spokeo and Intelius, also offer individual reference services that sell

personal identifying information about consumers to individuals or

companies.

In addition, many information resellers, such as Acxiom and LexisNexis,

offer products that companies use for marketing purposes. Resellers may

Background

Page 3 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

focus on groups of likely customers who share common characteristics,

and therefore may have similar interests or preferences. For example,

resellers may offer information products that allow clients to target their

online advertisements and help ensure that promotional materials are

sent to the most relevant individuals. Resellers may offer retailers the

ability to add purchase and lifestyle information to their existing customer

databases. In addition, resellers may offer clients marketing lists with

contact information of prospective customers.

Resellers maintain large, sophisticated databases with information from a

variety of sources about individuals and families. The consumer

information that each reseller maintains and sells varies, but can include

names, addresses, family members, neighbors, credit histories, motor

vehicle records, insurance claims, criminal records, employment histories,

incomes, ethnicities, purchase histories, interests, and hobbies. (See

appendix II for a detailed list of examples of the types of consumer

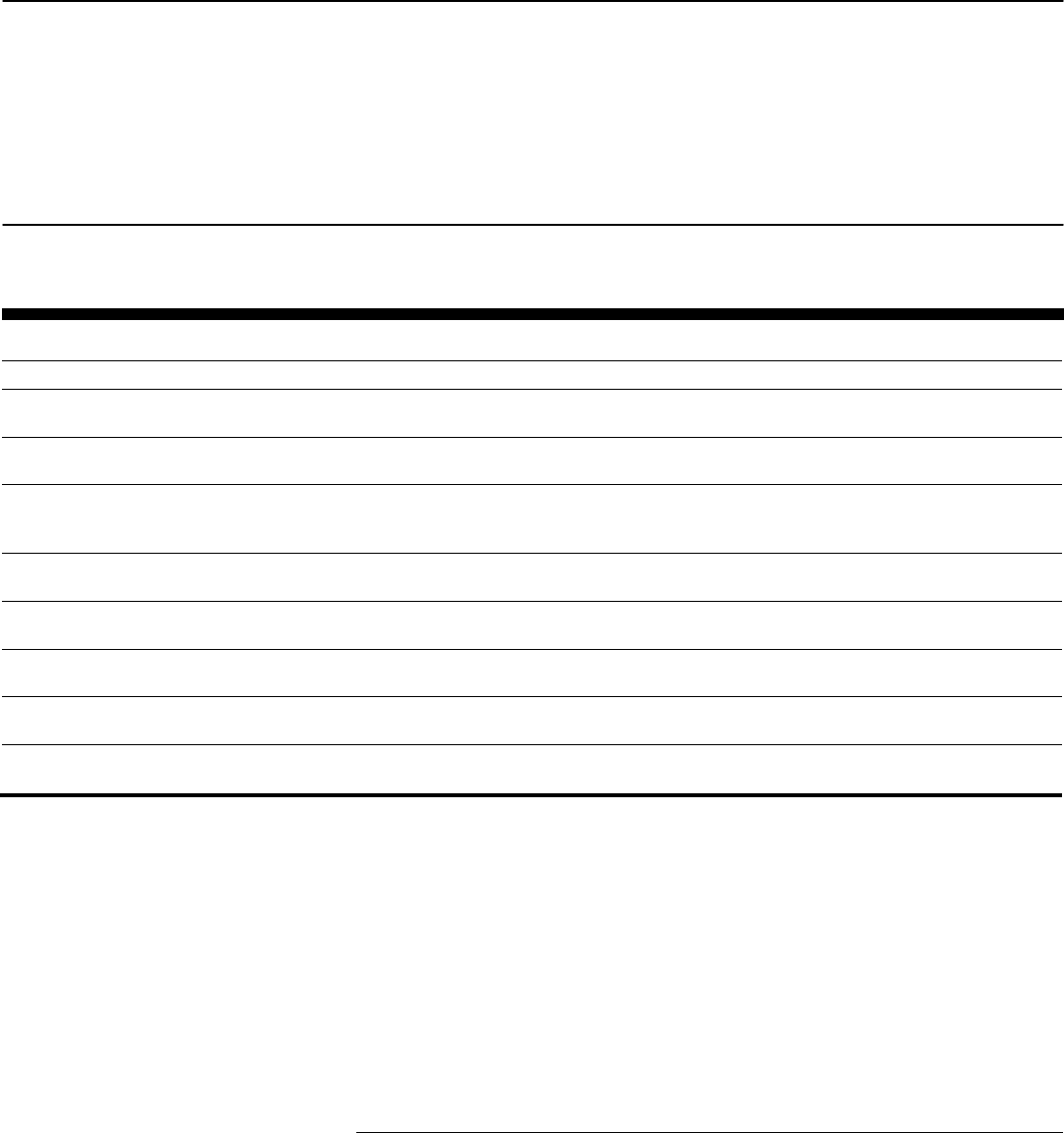

information held by information resellers.) As shown in figure 1, resellers

obtain their information from three primary types of sources: public

records, publicly available information, and nonpublic information.

Figure 1: Typical Flow of Consumer Data through Resellers to Third-Party Users

Page 4 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

• Public records, available to anyone, generally are obtained from

governmental entities. What constitutes a public record depends on

state and federal laws, but may include birth and death records,

property records, tax lien and assessor files, voter registrations,

licensing records, and court records (including criminal records,

bankruptcy filings, civil case files, and legal judgments).

• Publicly available information is not found in public records, but

nevertheless is publicly available through sources such as telephone

directories, business directories, classified advertisements,

newspapers or magazines, and other materials.

• Nonpublic information derives from proprietary sources. For example,

consumers may provide the information directly to businesses through

loyalty card programs at grocery or retail stores, website registrations,

warranty registrations, contests, surveys and questionnaires, and

purchase histories. Resellers (or a third party such as a website

operator acting on behalf of the reseller) also may collect nonpublic

information about consumers’ online locations and actions, including a

computer’s Internet protocol address, the browser used, activities

during a consumer’s visit to a website (such as search terms or

purchases), and activities conducted on other websites.

Consumer information can be derived from mobile networks, devices

(including smartphones and tablets), operating systems, and applications.

In addition, resellers may obtain personal information from the profile or

public information areas of websites, including social media sites such as

Facebook, LinkedIn, MySpace, and Twitter, or from information posted to

blogs or discussion forums. Depending on the context, information from

these sources may be publicly available or nonpublic.

There is limited publicly known information about the information reseller

industry as a whole. Characterizing the precise size and nature of the

industry can be difficult because definitions for resellers vary and data on

resellers often are limited or not comparable. For example, the U.S.

Census Bureau (Census) does not assign a business classification code

specific to information resellers. Instead, Census has assigned different

primary codes, including “data processing and preparation,” “direct mail

advertising services,” “credit reporting services,” and “information retrieval

Page 5 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

services.”

2

FTC has called on the information reseller industry to improve the

transparency of its practices, and in December 2012 issued orders

requiring nine information resellers to provide FTC with information about

how they collect and use data about consumers.

Thus, Census data cannot be used to provide a reliable count

or other statistical information on the information resellers industry as a

whole. According to FTC and Commerce, there is no comprehensive list

or registry of companies that resell personal information. Several privacy-

related organizations and websites maintain lists of information

resellers—for example, Privacy Rights Clearinghouse lists more than 250

on its website—but none of these lists claim to be comprehensive. The

Direct Marketing Association, which represents companies and nonprofits

that use and support data-driven marketing, maintains a proprietary

membership list, which it says numbers about 2,500 organizations

(although that includes retailers and others that typically would not be

considered information resellers).

3

The Fair Information Practice Principles (FIPPs) are a set of

internationally recognized principles for protecting the privacy and

security of personal information. A U.S. government advisory committee

first proposed the practices in 1973 in response to concerns about the

consequences computerized data systems could have on the privacy of

personal information. While the FIPPs are principles as opposed to legal

requirements, they provide a framework for balancing the need for privacy

with other interests. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

FTC sought details

about the nature and sources of the consumer information that

information resellers collect; how they use, maintain, and disseminate the

information; and the extent to which the companies allow consumers to

access and correct their information or opt out of having their personal

information sold. According to FTC staff, the agency expects to issue a

report with findings by the end of 2013.

2

Census assigns business classification codes, including Standard Industrial Classification

and North American Classification System codes, to each company to classify its main

industry and line of business.

3

Federal Trade Commission, Order to File Special Report, File No. P125404 (Dec. 14,

2012). The order was pursuant to the agency’s Resolution Directing Use of the

Compulsory Process to Collect Information Regarding Data Brokers, File No. P125404

(Dec. 14, 2012). The nine companies were Acxiom, CoreLogic, Datalogix, eBureau, ID

Analytics, Intelius, PeekYou, Rapleaf, and Recorded Future.

Page 6 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

Development (OECD) developed a revised version of the FIPPs in 1980

that has been widely adopted (see table 1).

4

Table 1: Fair Information Practice Principles

Principle Description

Collection limitation The collection of personal information should be limited, obtained by lawful and fair means, and, where

appropriate, with the knowledge or consent of the individual.

Data quality Personal information should be relevant to the purpose for which it is collected, and should be accurate,

complete, and current as needed for that purpose.

Purpose specification The purposes for the collection of personal information should be disclosed before collection and upon

any change to those purposes, and the use of the information should be limited to those purposes and

compatible purposes.

Use limitation Personal information should not be disclosed or otherwise used for other than a specified purpose

without consent of the individual or legal authority.

Security safeguards Personal information should be protected with reasonable security safeguards against risks such as loss

or unauthorized access, destruction, use, modification, or disclosure.

Openness The public should be informed about privacy policies and practices, and individuals should have ready

means of learning about the use of personal information.

Individual participation Individuals should have the following rights: to know about the collection of personal information, to

access that information, to request correction, and to challenge the denial of those rights.

Accountability Individuals controlling the collection or use of personal information should be accountable for taking

steps to ensure the implementation of these principles.

Source: OECD.

Many organizations and governments have used these principles, with

some variation, as best practices. In the United States, the FIPPs served

as the basis for the Privacy Act—which governs the collection,

maintenance, use, and dissemination of personal information by federal

agencies—and as the basis for many of the privacy recommendations of

agencies such as FTC and Commerce. The FIPPs also served as the

basis for a framework for consumer data privacy that the White House

issued in February 2012. This framework presents a consumer privacy bill

4

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Guidelines on the Protection

of Privacy and Transborder Flow of Personal Data (Paris, France: Sept. 23, 1980). OECD

produces internationally agreed-upon instruments, decisions, and recommendations to

promote rules in areas where multilateral agreement is necessary for individual countries

to make progress in the global economy. Its 30 member countries include the United

States. OECD has been reviewing whether its privacy guidelines should be revised or

updated to take into account the change in the role of personal data in the economy and

society.

Page 7 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

of rights, describes a stakeholder process to specify how the principles in

that bill of rights would apply, and encourages Congress to provide FTC

with enforcement authorities for the bill of rights.

5

Currently, no comprehensive federal privacy law governs the collection,

use, and sale of personal information by private-sector companies. There

are also no federal laws designed specifically to address all the products

sold and information maintained by information resellers. In contrast, a

baseline privacy law exists for personal information the federal

government maintains—the Privacy Act of 1974.

6

The act, among other

things, generally prohibits, subject to a number of exceptions, the

disclosure by federal entities of records about an individual without the

individual’s written consent and provides U.S. persons with a means to

seek access to and amend their records.

7

Many other industrialized

countries have implemented baseline privacy laws for information held by

private-sector companies. The 28 member countries of the European

Union have implemented into their national laws the union’s 1995 Data

Protection Directive, which provides a comprehensive framework on the

protection of personal data.

8

In the United States, the federal privacy framework for private-sector

companies comprises a set of more narrowly tailored laws that govern the

use and protection of personal information—that is, the laws apply for

specific purposes, in certain situations, to certain sectors, or to certain

types of entities. The primary federal laws with regard to consumer

privacy include the following:

It states that the personal information of

European Union citizens may not be transmitted to nations outside of the

union unless those countries are deemed to have “adequate” data

protection laws.

5

The White House, Consumer Data Privacy in a Networked World: A Framework for

Protecting Privacy and Promoting Innovation in the Global Digital Economy (Washington,

D.C.: Feb. 23, 2012).

6

Pub. L. No. 93-579, 88 Stat. 1896 (1974) (codified as amended at 5 U.S.C. § 552a).

7

5 U.S.C. § 552a.

8

European Union, Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on

the Protection of Individuals with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and the Free

Movement of Such Data (Oct. 24, 1995).

Several Laws

Apply in Specific

Circumstances to

Consumer Data That

Resellers Hold

Primary Federal Privacy Laws

Page 8 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA).

9

Enacted in 1970, FCRA protects the

security and confidentiality of personal information collected or used to

help make decisions about individuals’ eligibility for such products as

credit or for insurance or employment.

10

FCRA applies to “consumer

reporting agencies” that provide “consumer reports” that contain credit

histories and other personal information and are used for eligibility

determinations.

11

Accordingly, FCRA applies to the three nationwide

consumer reporting agencies (commonly called credit bureaus) and to

any other information resellers that resell consumer reports for use by

others. FCRA limits resellers’ use and distribution of personal data—for

example, by allowing consumers to opt out of allowing consumer

reporting agencies to share their personal information with third parties for

prescreened marketing offers. The act also allows individuals to access

and dispute the accuracy of personal data held on them. Additionally, as

amended in 2003, FCRA imposes safeguarding requirements designed to

prevent identity theft and assist identity theft victims.

12

Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA).

13

9

Pub. L. No. 91-508, Tit. VI, 84 Stat. 1114, 1128 (1970) (codified as amended at 15

U.S.C. §§ 1681-1681x).

Enacted in 1999, GLBA protects

nonpublic personal information that individuals provide to financial

10

See 15 U.S.C. § 1681.

11

FCRA defines a consumer reporting agency as “any person which, for monetary fees,

dues, or on a cooperative nonprofit basis, regularly engages in whole or in part in the

practice of assembling or evaluating consumer credit information or other information on

consumers for the purpose of furnishing consumer reports to third parties, and which uses

any means or facility of interstate commerce for the purpose of preparing or furnishing

consumer reports.” 15 U.S.C. § 1681a(f). The act defines consumer report as “any written,

oral, or other communication of any information by a consumer reporting agency bearing

on a consumer’s credit worthiness, credit standing, credit capacity, character, general

reputation, personal characteristics, or mode of living which is used or expected to be

used or collected in whole or in part for the purpose of serving as a factor in establishing

the consumer’s eligibility for (A) credit or insurance to be used primarily for personal,

family, or household purposes; (B) employment purposes; or (C) any other purpose

authorized under section 604 [of the FCRA],” subject to certain exclusions. 15 U.S.C. §

1681a(d).

12

Fair and Accurate Credit Transactions Act of 2003, Pub. L. No. 108-159, 117 Stat. 1952

(2003).

13

Pub. L. No. 106-102, 113 Stat. 1338 (1999) (codified as amended in scattered sections

of 12 and 15 U.S.C.).

Page 9 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

institutions or that such institutions maintain.

14

GLBA sharing and

disclosure restrictions apply to entities that fall under GLBA’s definition of

a “financial institution” or that receive nonpublic personal information from

such a financial institution.

15

The act’s privacy provisions restrict the

sharing of nonpublic personal information collected by or acquired from

financial institutions, which include those resellers covered by GLBA’s

definition of financial institution. Under a “reuse and redisclosure”

provision, a nonaffiliated third party that receives nonpublic personal

information from a financial institution faces restrictions on how it may

further share or use the information.

16

For example, a third party that

receives nonpublic personal information from a financial institution to

process consumers’ account transactions may not use the information for

its marketing purposes or sell it to another entity for marketing purposes.

GLBA requires financial regulators to establish appropriate standards for

financial institutions relating to administrative, technical, and physical

safeguards to ensure the security and confidentiality of customer records

and information; protect against any anticipated threats or hazards to the

security or integrity of such records; and protect against unauthorized

access to or use of such records or information that could result in

substantial harm or inconvenience to any customer.

17

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

18

14

See 15 U.S.C. §§ 6801-6802. Subtitle A of Title V of the act contains the privacy

provisions relating to the disclosure of nonpublic personal information. 15 U.S.C. §§ 6801-

6809.

Enacted in 1996, HIPAA establishes a set of national standards for the

protection of certain health information. The HIPAA privacy rule governs

the use and disclosure of an individual’s health information for purposes

15

15 U.S.C. § 6802. GLBA defines a “financial institution” as any institution the business of

which is engaging in financial activities as described in section 4(k) of the Bank Holding

Company Act (12 U.S.C. § 1843(k)). 15 U.S.C. § 6809(3)(a). Such activities include

lending, providing financial or investment advice, and insuring against loss.

16

15 U.S.C. § 6802(c).

17

15 U.S.C. § 6801. For example, the FTC safeguards rule implements GLBA’s

requirements for entities that fall under FTC jurisdiction, including check-cashing

businesses, payday lenders, and mortgage brokers. See 15 C.F.R. Part 314.

18

Pub. L. No. 104-191, 110 Stat. 1936 (1996) (codified as amended in scattered sections

of 18, 26, 29, and 42 U.S.C.).

Page 10 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

including marketing.

19

According to guidance from the Department of

Health and Human Services, the rule aims to strike a balance that permits

important uses of information in the provision of health care while

protecting patients’ privacy.

20

With some exceptions, the rule requires an

individual’s written authorization before a covered entity—a health care

provider that transmits health information electronically in connection with

covered transactions, health care clearinghouse, or health plan—may use

or disclose that individual’s protected health information for marketing.

21

In addition, HIPAA requires covered entities to safeguard protected

personal health information and protect against any reasonably

anticipated unauthorized uses or disclosures of such information, among

other things.

22

Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA).

The act does not directly restrict the use, disclosure, or

resale of protected health information by information resellers or other

parties not considered HIPAA-covered entities.

23

Enacted in 1998,

COPPA governs the online collection of personal information from

children under 13 by operators of websites or online services, including

mobile applications.

24

19

45 C.F.R. Parts 160, 164.

Specifically, COPPA and its implementing

regulations apply to the collection of personal information—such as full

name, e-mail address, or geolocation information—that would allow

someone to identify or contact a child. The law requires covered website

and online service operators to obtain verifiable parental consent before

collecting such information. It also specifies what information must be

included in the notice provided to parents and how and when to acquire

20

Department of Health and Human Services, “Summary of HIPAA Privacy Provisions,”

last revised May 2003, available at

http://hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/summary/.

21

The HIPAA privacy rule carves out specific exceptions to its definition of “marketing” that

include communications regarding refill reminders, communications to individuals from a

covered entity’s benefit plan that describe health-related products or services provided by

or included in a benefit plan, communications about participating providers in a provider or

health plan network, communications for treatment of individuals, and communications for

case management or care coordination for an individual. 45 C.F.R. § 164.501.

22

42 U.S.C. § 1320d-2(d)(2); see also 45 C.F.R. Part 164, Subpart C.

23

Pub. L. No. 105-277, Div. C, Tit. XIII, 112 Stat. 2681-728 (1998) (codified at 15 U.S.C.

§§ 6501-6506).

24

FTC issued regulations implementing COPPA, 16 C.F.R. Part 312.

Page 11 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

parental consent. Although COPPA may not directly affect information

resellers, COPPA governs information collection by operators of websites

and online services, both of which are potential sources of personal

information for resellers and other parties. COPPA would not apply to the

collection of a child’s information from the child’s parent or other adults.

Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA).

25

Among its

provisions, ECPA, which was enacted in 1986, prohibits the interception

and disclosure of electronic communications by third parties unless an

exception applies, such as one of the parties to the communication

having consented to the interception or disclosure.

26

For example, the act

would prevent an Internet service provider from selling the content of its

customers’ e-mails and text messages to an information reseller that

wanted to use the content for marketing purposes unless the customers

had given their consent for the disclosures. However, ECPA provides

more limited protection for information that is considered to be “non-

content”, such as a customer’s name and address.

27

Federal Trade Commission Act (FTC Act), Section 5.

28

25

Pub. L. No. 99-508, 100 Stat. 1848 (1986) (codified as amended in scattered sections of

18 U.S.C.).

Enacted in

1914, the FTC Act prohibits unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or

affecting commerce. Although the act does not explicitly grant FTC the

specific authority to protect privacy, it has been interpreted to apply to

deceptions or violations of written privacy policies. For example, if a

retailer had a written privacy policy stating it would not share customers’

personal information with resellers or other third parties for any purposes

and later breached the policy by selling the information to such parties,

FTC could prosecute the retailer for unfair and deceptive practices.

Likewise, the act would apply to resellers if they used personal

information for purposes prohibited by their written privacy policies. In

26

See 18 U.S.C. §§ 2701-2712.

27

18 U.S.C. § 2703(c)(2), cited by U.S. Department of Justice, Computer Crime and

Intellectual Property Section, Searching and Seizing Computers and Obtaining Electronic

Evidence in Criminal Investigations, Chapter 3 (2009), available at

http://justice.gov/criminal/cybercrime/docs/ssmanual2009.pdf.

28

15 U.S.C. § 45. Section 5 of the FTC Act, as originally enacted, only related to “unfair

methods of competition.” The Wheeler-Lea Act, passed in 1938, expanded the

Commission’s jurisdiction to include “unfair or deceptive acts or practices.” Wheeler-Lea

Amendments of 1938, Pub. L. No. 75-447, 52 Stat. 111.

Page 12 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

addition, the FTC Act’s unfairness authority could apply, even in the

absence of a privacy policy, in situations involving a likelihood of

substantial injury to consumers that is not reasonably avoidable and not

offset by countervailing benefits. In effect, FTC enforcement actions can

establish compliance requirements that companies can follow in order to

avoid future enforcement actions.

29

As they relate to specific types of consumer services or types of records,

other federal privacy laws that also may apply to information resellers’

practices and products include the following:

30

Driver’s Privacy Protection Act.

31

Enacted in 1994, the act generally

prohibits the use and disclosure of certain personal information in state

motor vehicle records.

32

The act also specifies permissible uses of

personal information, and that an authorized recipient of personal

information may “resell or redisclose” the information only for purposes

permitted by law.

33

For example, a state department of motor vehicles

cannot sell drivers’ personal information to resellers for marketing

purposes unless the department obtained consent from the individuals.

34

29

FTC has also required implementation of a comprehensive privacy policy as part of the

settlement of FTC charges. See In the Matter of Google Inc., FTC File No. 102 3136,

decision and order (Oct. 13, 2011).

30

While these are some relevant examples of subject-specific privacy laws, this is not a

comprehensive list of all federal privacy laws that could apply to information resellers.

31

Pub. L. No. 103-322, Tit. XXX, 108 Stat. 2099 (1994) (codified as amended at 18 U.S.C.

§§ 2721-2725).

32

See 18 U.S.C. § 2721.

33

Permissible uses include use by a government agency in carrying out its functions and

uses related to matters of motor vehicle or driver safety and theft. See 18 U.S.C. §

2721(b) for a complete listing of permissible uses.

34

In July 2013, the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit determined that data brokers

could be liable for the use of personal information that they obtain from state departments

of motor vehicles and sell to others. The court held that the Driver’s Privacy Protection Act

imposes a duty on resellers to exercise reasonable care in responding to requests for

personal information drawn from motor vehicle records. Gordon v. Softech, Int’l, Inc., No.

12-661-cv. 2013 WL 3939442, at *12 (2d Cir. July 31, 2013).

Selected Additional

Applicable Laws

Page 13 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act.

35

Enacted in 1974, the act

governs access to and disclosure of students’ education records to

parents, students, and third parties. Specifically, the act provides that no

federal funds shall be made available to any school or institution that has

a policy of releasing students’ education records or personally identifiable

information contained in such records (other than directory information) to

third parties such as information resellers (other than to certain parties

and for certain purposes enumerated in the statute) without written

consent from the students’ parents.

36

,

37

Video Privacy Protection Act.

38

Enacted in 1988, the act prohibits a

video tape service provider from knowingly disclosing personally

identifiable information concerning video rental and sales records,

including the title or subject matter of any video tapes, to third parties,

subject to exceptions.

39

Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA).

However, a provider may disclose the names and

addresses of consumers to third parties if the consumer has had the

opportunity to prohibit such disclosure. The provider also may disclose

the content of rental materials if that information will be used only to

market goods and services directly to the consumer.

40

35

Pub. L. No. 93-380, Tit. V, § 513, 88 Stat. 57 (1974) (codified as amended at 20 U.S.C.

§ 1232g).

Enacted in 1986, CFAA

makes the knowing unauthorized access of computers a crime. CFAA is

not specifically a privacy law but can serve to restrict a third party from

36

20 U.S.C. § 1232g(b)(1). A student may provide consent to release education records

and personal information if he or she is 18 years of age or older or is attending a

postsecondary education institution. For students younger than 18, consent of their

parents is necessary. See 20 U.S.C. § 1232g(d).

37

For the purposes of this section, the term “directory information” relating to a student

includes the following: the student’s name, address, telephone listing, date and place of

birth, major field of study, participation in officially recognized activities and sports, weight

and height of members of athletic teams, dates of attendance, degrees and awards

received, and the most recent previous educational agency or institution attended by the

student. See 20 U.S.C. § 1232g(a)(5)(A).

38

Pub. L. No. 100-618, 102 Stat. 3195 (1988) (codified as amended at 18 U.S.C. § 2710).

39

18 U.S.C. § 2710.

40

Pub. L. No. 99-474, 100 Stat. 1213 (1986) (codified as amended at 18 U.S.C. § 1030).

Page 14 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

collecting personal information from a website when the collection would

violate the site’s terms of service.

41

Telecommunications Act.

42

Enacted in 1996, the act requires

telecommunications carriers to protect the confidentiality of proprietary

information of customers.

43

While we did not conduct a comprehensive review of all state laws, we

identified relatively few state laws that broadly address consumer privacy

rights or regulate information resellers. Representatives of several privacy

advocacy organizations similarly noted that few state laws broadly

address information resellers or consumer privacy, such as the collection

or disclosure of personal information held by private companies.

However, some states have enacted laws designed to improve data

security and reduce identity theft, such as laws requiring consumer

notification of security breaches involving personal information.

Additionally, the act prohibits carriers from

using proprietary information from other carriers for their own marketing

efforts.

44

In addition, we reviewed the laws of four states that impose disclosure

requirements related to the sharing of personal information about

41

Courts have held that CFAA prohibits access to websites when that access exceeds the

sites’ terms of use or end-user license agreements. See, e.g., Snap-On Bus. Solutions

Inc. v. O’Neil & Assoc., Inc., 708 F.Supp. 2d 669 (N.D. Ohio 2010); Southwest Airlines Co.

v. Farechase, Inc., 318 F.Supp. 2d 435 (N.D. Tex. 2004); America Online, Inc. v. LCGM,

Inc., 46 F.Supp. 2d 444 (E.D. Va. 1998).

42

Pub. L. No. 104-104, 110 Stat. 56 (1996) (codified as amended in scattered sections of

15 and 47 U.S.C.).

43

47 U.S.C. § 222(a).

44

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, as of August 2012, 46

states, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands had enacted

legislation requiring data-breach notifications. In general, these states and territories

require companies to notify state or territorial residents if their personal information in the

companies’ custody was compromised. See National Conference of State Legislatures:

State Security Breach Notification Laws, available at http://www.ncsl.org/issues-

research/telecom/security-breach-notification-laws.aspx.

Selected State Privacy Laws

Page 15 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

consumers.

45

California’s Shine the Light law requires certain businesses

to disclose, upon a California customer’s request, whether those

businesses have shared the customer’s personal information with third

parties for direct marketing purposes.

46

For certain specified categories of

information, the business also must notify the requesting consumer of the

categories of information shared with a third party.

47

Similarly, Utah’s

Notice of Intent to Sell Nonpublic Personal Information Act requires

commercial entities to disclose to consumers the types of nonpublic

personal information shared with or sold to third parties for

compensation.

48

Massachusetts and Nevada have laws or regulations

requiring businesses to safeguard and encrypt personally identifiable

consumer data. The Massachusetts regulations establish minimum

standards for safeguarding personal information in both paper and

electronic records and cover only personal information about residents of

Massachusetts.

49

The Nevada law generally covers any personal

information belonging to certain categories that a business maintains.

50

45

In 2011, the Supreme Court determined that a Vermont law that restricted the sale,

disclosure, and use of pharmacy records that reveal the prescribing practices of individual

doctors violated the First Amendment. The Vermont law provided that the prescriber-

identifying information could not be sold by pharmacies for marketing purposes or used for

marketing by pharmaceutical manufacturers. Pharmacies could share the information with

anyone for any purpose except marketing. The Court determined that these content-and-

speaker-based restrictions on speech were subject to heightened judicial scrutiny.

Vermont’s asserted interest in physician confidentiality did not withstand the heightened

scrutiny. Sorrell v. IMS Health, Inc, 131 S.Ct. 2653 (2011).

46

Cal. Civ. Code § 1798.83 (West). Any California resident with whom a business has an

established business relationship is entitled to disclosure of the business’s information-

sharing practices. The law applies to many businesses, but those with fewer than 20

employees and certain financial institutions that are in compliance with separate privacy

requirements are exempt.

47

These categories include, among other things, the customer’s height, race, religion,

telephone number, number of children, medical condition, Social Security number, bank

account number, and credit card balance. Cal. Civ. Code § 1798.83(e)(6).

48

Utah Code Ann. §§ 13-37-101 to -203 (West).

49

201 Mass. Code Regs. 17.01 to 17.05.

50

Nev. Rev. Stat. §§ 603A.010 to .920. The encryption and security measure requirements

do not apply to data transmitted over a secure, private communication channel for

approving or processing negotiable instruments, electronic fund transfers, or similar

methods.

Page 16 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

For consumer data used for marketing purposes, the privacy protections

provided under federal law have been limited. Although the FIPPs call for

restraint in the collection and use of personal information, the scope of

protections provided under current law has been narrow in relation to (1)

individuals’ ability to access, control, and correct their personal data; (2)

collection methods and sources and types of consumer information

collected; and (3) new technologies, such as tracking of web activity and

the use of mobile devices. However, views differ on whether privacy

protections should be expanded and if this could best be done through

legislation or self-regulation.

Current federal privacy laws generally do not provide individuals the

universal right to access, control, or correct personal information that

resellers and private-sector companies use for marketing purposes. The

“collection limitation” and “openness” principles of the FIPPs state that

individuals should be able to know about and consent to the collection of

their personal information, while the “individual participation” principle

states they should have the right to access that information, request

correction, and challenge the denial of those rights. However, none of the

federal statutes that we examined generally requires information resellers

to allow individuals to review their personal information in the resellers’

possession intended for marketing or information retrieval purposes,

control its use, or correct it.

In relation to data used for marketing purposes, no federal statute

provides consumers the right to learn what information is held about them

and who holds it. As noted earlier, FCRA provides individuals with rights

to access information from consumer reports used for eligibility

determinations, but does not apply to personal information used for

marketing (other than prescreened marketing offers). For example, an

information reseller we interviewed said the company generally does not

offer consumers the ability to see the personal information held about

them for purposes not covered under FCRA. Additionally, in 2006 some

resellers told us that they gave individuals opportunities to order summary

reports that disclosed personal information maintained for non-FCRA

purposes, but the extent of the information provided varied.

51

51

GAO-06-674.

Existing Privacy Laws

Have Limited Scope

over Personal Data

Used for Marketing

Laws Provide Individuals

Limited Ability to Access,

Control, and Correct Their

Personal Data

Access rights

Page 17 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

Consumers have limited legal rights to control what personal information

is collected, maintained, used, and shared and how. Under FCRA,

individuals can request that personal information not be shared with third

parties for marketing unsolicited prescreened credit or insurance offers.

GLBA’s privacy provisions generally limit financial institutions from

sharing nonpublic personal information with nonaffiliated third parties

without first providing certain notice and, in some cases, opt-out rights to

customers and other consumers. However, apart from these two cases,

individuals do not have a right to require that their personal information

not be collected, used, and shared for marketing purposes. Some trade

associations, information resellers, and other companies voluntarily have

developed opt-out mechanisms through which consumers can request

that their personal information be excluded from resellers’ marketing

databases.

52

The Digital Advertising Alliance also has a program that

calls for its members to provide consumer control over what data are

collected and used for online behavioral or interest-based advertising.

53

No federal law that we examined provides correction rights for information

used for marketing or look-up purposes. Correction refers to consumers’

ability to have resellers and other parties correct or delete inaccurate,

incomplete, or unverifiable information. For information covered under

FCRA, consumers have the right to dispute information held by resellers

that is incomplete or inaccurate, have a claim investigated, and have any

errors deleted or corrected. However, neither FCRA nor any other federal

52

For example, on September 4, 2013, Acxiom unveiled an online consumer site

(AboutTheData.com) that, according to Acxiom, will allow consumers to view and edit the

data about them that Acxiom clients use for digital marketing. Additionally, the site will give

consumers the ability to opt-out, or exclude their personal information from Acxiom's

marketing database, according to the company.

53

In online behavioral advertising, information about a consumer’s computer browser

habits helps build a profile about the computer user that can be used to target the specific

web-based advertisements shown to that computer user. Advertising and marketing trade

associations formed the nonprofit Digital Advertising Alliance in 2008 to develop and

administer principles for online data collection and use. In October 2010, the industry

created a self-regulatory program that was based on its Self-Regulatory Principles for

Online Behavioral Advertising (issued in 2009). The program calls on member companies

engaging in online behavioral advertising to provide (1) transparency about data

collection; (2) consumer control over whether data are collected and used; (3) security for

and limited retention of data collected and used; (4) consent to changes in an entity’s data

collection and use policies; and (5) limitations on the collection of specified categories of

sensitive data for online behavioral advertising purposes.

Control rights

Correction rights

Page 18 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

law that we examined provides similar correction rights for information

used for marketing or look-up purposes.

The “data quality” and “purpose specification” principles of the FIPPs

state that personal information should be relevant and limited to the

purpose for which it was collected, and the “collection limitation” principle

calls for confining the collection of personal information. However, the

scope of current federal privacy laws is limited in addressing the methods

by which, or the sources from which, information resellers and private-

sector companies collect and aggregate personal information, or the

types of information that may be collected for marketing or look-up

purposes.

Federal laws generally do not govern the methods resellers may use to

collect personal information for marketing or look-up purposes. Examples

of such methods include “web scraping”—sometimes called data

extraction or web data mining—in which resellers, advertisers, and other

parties use software to search the web for information about an individual

or individuals, and extract and download bulk information from a particular

website that contains consumer information. The marketing material of

one company we reviewed advertised that for a fee it would provide

information on any individual by extracting data and photographs from

social media websites, blogs, or telephone and professional directory

sites that contain e-mail addresses and other contact information. A

website’s terms-of-use may legally restrict such practices or password

protections may help prevent them. Resellers or retailers also may collect

personal information through indirect means. For example, some retailers

ask consumers to provide their zip code when using a credit card at the

time of purchase. The zip code can be combined with the name on the

credit card to determine the consumer’s address, telephone number, or

other personal information that may be held in a marketing database.

Current law generally allows resellers to collect personal information from

sources that include warranty registration cards, consumer surveys, and

retailers, and online sources such as discussion boards, social media

sites, blogs, web browsing histories, and searches. Current law does not

require disclosure to consumers when their information is collected from

these sources, including when consumers are unaware that the

information will be used for marketing purposes.

Laws Largely Do

Not Address Data

Collection Methods,

Sources, and Types

Methods for collecting

personal data

Sources of personal data

Page 19 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

The federal laws that address the types of consumer information that can

be collected and shared for marketing and look-up purposes have limited

reach and application. Under most circumstances, information that many

people may consider very personal or sensitive legally can be collected,

shared, and used for marketing purposes. This can include information

about an individual’s physical and mental health, income and assets,

mobile telephone numbers, shopping habits, personal interests, political

affiliations, and sexual habits and orientation. For example, in 2009

testimony before Congress, a representative of the World Privacy Forum

said that some marketers maintain lists that contain information on

individuals’ medical conditions, including mental health conditions.

54

HIPAA provisions apply only to covered entities and not, for example, to

health-related marketing lists used by e-health websites or other

noncovered entities. Information resellers that do not qualify as covered

entities can collect and use information about consumers’ health histories

and treatments for marketing purposes. Although federal laws generally

do not restrict the types of information resellers can collect and share for

marketing, many companies voluntarily follow guidelines that recognize

that sensitive personal information merits different treatment. For

example, industry principles for online behavioral advertising call for

consent from individuals for the collection of certain sensitive personal

information—including financial account numbers, pharmaceutical

prescriptions, and medical records.

55

The current privacy framework does not fully address new technologies.

Developments such as social media, web tracking technologies, and

mobile devices have enabled even cheaper, faster, and more detailed

data collection and sharing among resellers and private-sector

companies. In a 2013 report, FTC staff noted that the rapid growth of

mobile technologies provided substantial benefits to both businesses and

consumers, but also presented unique privacy challenges because

54

House Committee on Energy and Commerce, Subcommittee on Communications,

Technology, and the Internet, and Subcommittee on Commerce, Trade, and Consumer

Protection, Exploring the Offline and Online Collection and Use of Consumer Information,

111th Cong., 1st sess., Nov. 19, 2009; see testimony of Pam Dixon, Executive Director,

World Privacy Forum.

55

Digital Advertising Alliance, Self-Regulatory Principles Overview, Principles for Online

Behavioral Advertising, available at http://aboutads.info/obaprinciples. For personal

information of children, the principles purport to apply the protective measures in COPPA.

Types of information collected

Current Law Does Not

Directly Address Some

Privacy Issues Raised

by New Technology

Page 20 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

mobile devices generally were personal to an individual, almost always

on, could facilitate large amounts of data collection and sharing among

many entities, and could identify a user’s geographical location.

56

56

Federal Trade Commission, Mobile Privacy Disclosures: Building Trust through

Transparency (Washington, D.C.: February 2013).

As

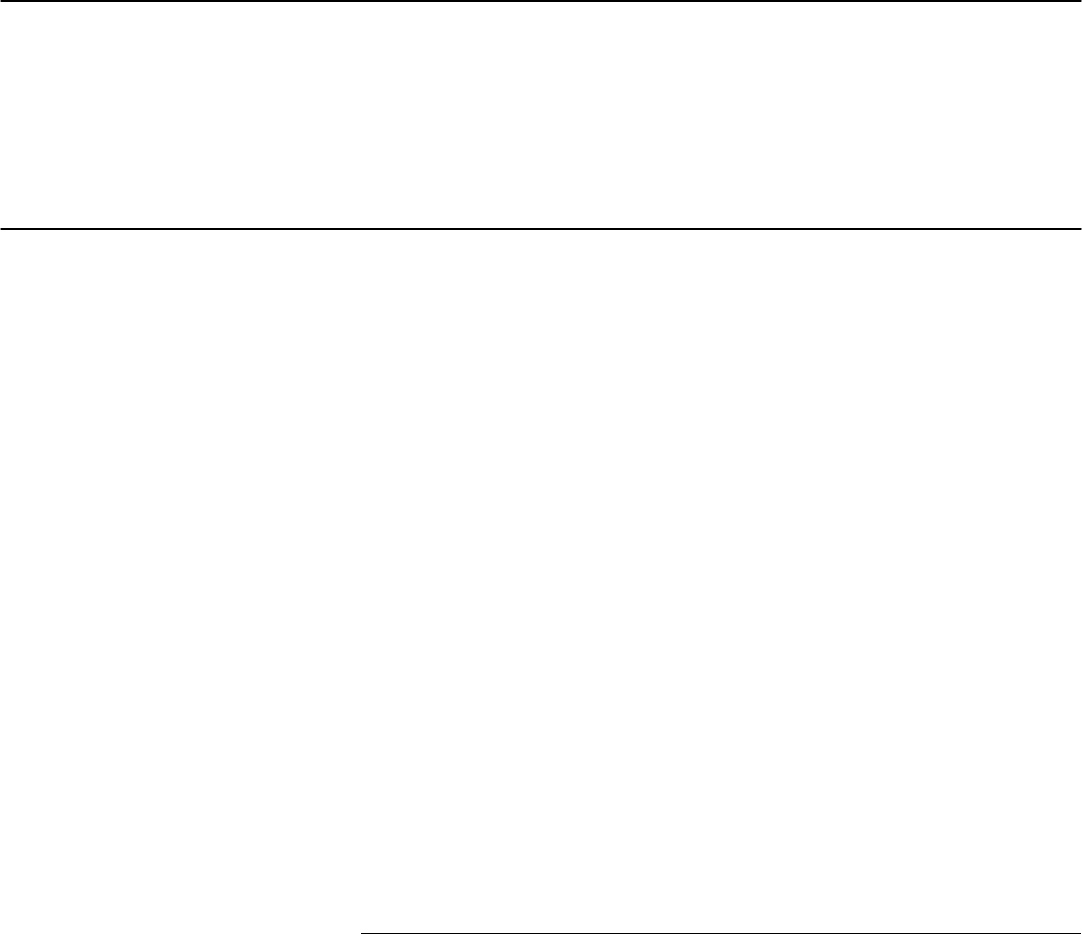

shown in figure 2, the original enactment of several federal privacy laws

predate these trends and technologies.

Page 21 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

Figure 2: Dates of Enactment of Key Federal Privacy Laws and the Introduction of

New Technologies

Page 22 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

Note: The most recent amendments to the federal laws referenced in figure 2 are as follows:

• Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914: last amended on July 21, 2010 (Pub. L. 111-203).

• Fair Credit Reporting Act of 1970: last amended on Dec. 18, 2010 (Pub. L. No. 111-319).

• Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974: last amended on Jan. 14, 2013 (Pub. L.

No. 112-278).

• Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986: last amended on Oct. 19, 2009 (Pub. L.

No. 111-79).

• Video Privacy Protection Act of 1988: last amended on Jan. 10, 2013 (Pub. L. No. 112-

258).

• Driver’s Privacy Protection Act of 1994: last amended on Oct. 23, 2000 (Pub. L. No. 106-

346).

• Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996: last amended Mar. 23, 2010

(Pub. L. No. 111-148).

• Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998: has not been amended.

• Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999: last amended on July 21, 2010 (Pub. L. No. 111-203).

Because these laws were enacted to protect the privacy of information

involving specific sectors rather than address specific technologies, some

have been interpreted to apply in the case of new technologies. For

example, as discussed later in this report, FTC has taken enforcement

activity under COPPA and revised the statute’s implementing regulations

to account for smartphones and mobile applications. However, online

tracking practices and mobile devices remain areas in which privacy law

has not fully addressed issues raised by new technologies.

Currently, no federal privacy law explicitly addresses the full range of

practices to track or collect data from consumers’ online activity.

Cookies—small text files placed on an individual computer by the website

that the person visits—represent a common method of tracking online

activity. The information stored in cookies allows website operators to

determine whether users are repeat visitors, and allows for the recall of

information users may have entered such as name and address, credit

card number, site settings, and purchases in a shopping cart. Information

resellers can use the information in cookies to supplement information

from their databases—matching information by individuals’ name and e-

mail addresses—to augment profiles on individual consumers. Third

parties also can synchronize their cookie files with resellers’ cookie files

to obtain additional information to enhance consumer profiles. Some

advertisers use so-called third-party cookies—placed on a visitor’s

computer by a domain other than the site being visited—to track visits to

the various websites on which they advertise. Although not required by

law, some web browsers, such as Apple’s Safari and Mozilla’s Firefox,

have privacy settings that allow users to block third-party cookies or turn

Online Tracking

Page 23 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

on do-not-track features.

57

Additionally, new methods of tracking consumers’ online behavior seek to

restrict consumers’ ability to prevent such tracking. For example,

according to a 2009 study, an online advertising company developed

flash cookies, which combat users’ ability to delete cookies.

However, honoring the do-not-track setting is

voluntary on the part of website operators.

58

While current law does not explicitly address the use of web tracking,

FTC has taken enforcement actions related to web tracking under its

authority to enforce the prohibition of unfair or deceptive acts or practices.

For example, in 2011, FTC settled charges with Google for $22.5 million

after alleging that Google violated an earlier privacy settlement with FTC

when it misrepresented to users of Apple’s Safari web browser that it

would not track and serve targeted advertisement to Safari users.

Such

cookies can contain up to 25 times more data than other cookies, do not

expire at the end of a browsing session, and cannot be erased through

web browser features such as “clear history.” The study found that many

popular websites, such as Google and Facebook, had been using flash

cookies to recreate deleted cookies.

59

57

For example, Safari blocks third-party cookies by default. Firefox users can approve or

deny cookie storage requests and disable third-party cookies. Additionally, Safari and

Firefox do-not-track features notify websites visited—and their advertisers—that web

users do not want to be tracked online. Mozilla also offers a downloadable program, called

Better Privacy, to combat and remove flash cookies. Finally, other companies have

developed privacy and security software programs to detect and block third parties from

tracking web users online.

According to FTC, Google had placed advertising tracking cookies on

individuals’ computers and falsely represented that because of Safari’s

default settings, individuals automatically would be “opted out” of cookie

tracking. Instead, Google’s tracking cookies circumvented Safari’s default

settings, which enabled the company to use these cookies to track

individuals and present them with targeted advertisements. As a result of

58

Shannon Canty, Chris Jay Hoofnagle, et al., “Flash Cookies and Privacy” (Aug. 10,

2009), available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1446862.

59

United States v. Google Inc., No. CV 12-04177-SI, 2012 WL 5833994 (N.D. Cal. Nov.

16, 2012).

Page 24 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

the settlement, Google agreed to disable its use of advertising tracking

cookies.

60

Federal law also does not expressly prohibit “history sniffing,” which uses

software code on a webpage to record the browsing history of page

visitors. However, in 2012, FTC took an enforcement action against Epic

Marketplace, a large online advertising network, for deceptively failing to

disclose its use of history-sniffing technology.

61

In relation to collection and use of consumer data for marketing, no

federal privacy laws that we identified specifically govern mobile

applications and technologies.

The company allegedly

collected data about the web sites that consumers were visiting, including

sites relating to potentially sensitive topics such as impotence,

menopause, disability insurance, debt relief, and personal bankruptcy.

Epic Marketplace used this information to assign consumers into interest

segments that were used to target advertising.

Mobile applications. While various federal laws apply to activity

conducted through mobile applications or mobile technologies, no federal

law specifically governs mobile applications—software programs

downloaded onto mobile devices for uses such as providing news and

60

In December 2011, FTC finalized a settlement order with the online advertiser

ScanScout, which FTC alleged deceptively had claimed that consumers could opt out of

receiving targeted advertisements by changing their browser settings, whereas in fact,

ScanScout used flash cookies that browser settings could not block. In the Matter of

ScanScout, FTC File No. 102 3185, decision and order (Dec. 14, 2011). In October 2012,

a web analytics company settled FTC charges that it violated the FTC Act by using web

tracking software that collected personal data without disclosing the extent of information

that it was collecting, In the Matter of Compete, Inc., FTC File No. 102-3155, decision and

order (Feb. 20, 2013).

61

FTC alleged that Epic Marketplace’s use of history-sniffing technology was deceptive

because it collected data about sites outside of its network that consumers had visited,

contrary to Epic’s privacy policy, which represented that it would collect information only

about consumers’ visits to websites in its network. In the Matter of Epic Marketplace, Inc.,

and Epic Media Group, LLC, FTC File No. 112 3182, decision and order (Mar. 13, 2013).

Mobile Technologies

Page 25 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

information and online banking and shopping.

62

Application developers,

operating system developers, mobile carriers, advertisers, advertising

networks, and other third parties may collect an individual’s information

through services provided on his or her device. They may use this

information to create a user profile to tailor marketing and they may sell

information collected from these devices to third parties. FTC has taken

enforcement action against companies for use of mobile applications that

violate COPPA and FCRA.

63

The agency has taken action under the FTC

Act in cases in which a mobile application developer collected or used

personal information in a manner inconsistent with the application’s

privacy policy.

64

In addition, CFAA, which bans unauthorized access to

computers, also has been found to apply to mobile phones.

65

Location tracking. No federal privacy laws that we evaluated, with the

exception of COPPA, expressly address location data, location-based

technology, and consumer privacy. Smartphones and other mobile

devices can provide services based on a consumer’s location. We and

others have reported that this capability engenders potential privacy risks,

particularly if companies use or share location data without consumers’

62

On July 25, 2013, the Department of Commerce released a draft of a voluntary code of

conduct for mobile applications. The code sets out guidelines for short form notices that

application developers and publishers can use to inform consumers about the collection

and sharing of consumer information with third parties. See Department of Commerce,

National Telecommunications and Information Administration, Short Form Notice Code of

Conduct To Promote Transparency In Mobile App Practices, redline draft (July 25, 2013),

available at http://www.ntia.doc.gov/files/ntia/publications/july_25_code_draft.pdf.

63

FTC settled charges that a social networking service deceived consumers when it

illegally collected information from children under 13 through its mobile application, in

violation of COPPA. See United States v. Path, Inc., No. C13-0448 (N.D. Cal. Jan. 31,

2013). Additionally, FTC settled charges that a company compiled and sold criminal

record reports through its mobile application and operated as a consumer reporting

agency, in violation of FCRA. See In the Matter of Filiquarian Publishing, LLC, FTC File

No. 112 3195 (Apr. 30, 2013).

64

For example, in the Path enforcement action, in addition to the alleged violation of

COPPA, Path allegedly deceived users by collecting personal information from their

mobile device address books without their knowledge and consent. See United States v.

Path, Inc., No. C13-0448 (N.D. Cal. Jan. 31, 2013).

65

In 2011, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit held that a basic cellular

telephone—used only to place calls and send text messages—was a computer for the

purposes of CFAA. The judicial decision did not address more advanced devices, such as

smartphones, in the CFAA context. See U.S. v. Kramer, 631 F.3d 900 (8th Cir. 2011).

Page 26 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

knowledge.

66

In 2010, Commerce recommended that the Administration

review ECPA to address privacy protection of location-based services.

67

Mobile payments. No federal privacy laws that we evaluated expressly

address mobile payments. Such services, which allow individuals to

transfer money or pay for goods and services using their mobile devices,

have become increasingly prevalent. According to a survey conducted by

the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 6 percent of

smartphone users used their telephones at cash registers to pay for

purchases in 2012.

As noted previously, ECPA generally prohibits the interception and

disclosure of individuals’ electronic communications, but this may not

apply if location data were not deemed content. ECPA also would not

govern the interception or access of information transmitted and stored by

entities not covered by ECPA, which typically would include developers of

location-based applications. However, COPPA regulations govern the

collection of geolocation data sufficient to identify street name and the

name of a city or town from children under 13, and FTC could pursue

enforcement action if a location-based provider’s collection or use of

geolocation information violated COPPA.

68

66

In 2012, we reported that the risks of mobile technologies included disclosure to third

parties for unspecified uses, the tracking of consumer behavior (location tracking can be

combined with tracking of online activity), and identity theft. For example, criminals can

use disclosed location and other sensitive information to steal identities. See GAO, Mobile

Device Location ID: Additional Federal Actions Could Help Protect Consumer Privacy,

A 2013 report by FTC noted that although mobile

payment can be an easy and convenient way for individuals to pay for

goods and services, privacy concerns have arisen because of the number

of companies involved in the mobile payment marketplace and the large

GAO-12-903 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 11, 2012). A Federal Communications Commission

report also noted privacy risks, particularly because numerous third parties can access

consumers’ personal information through location-based applications. See Federal

Communications Commission, Location-Based Services: An Overview of Opportunities

and Other Considerations (Washington, D.C.: May 2012).

67

See Department of Commerce, Internet Policy Task Force, Commercial Data Privacy

and Innovation in the Internet Economy: A Dynamic Policy Framework (Washington, D.C.:

December 2010).

68

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Consumers and Mobile Financial

Services 2013 (Washington, D.C.: March 2013).

Page 27 GAO-13-663 Information Resellers

amount of detailed personal and purchase information collected and

consolidated in the process.

69

Stakeholder views have diverged on whether significant gaps in the

current legal framework for privacy exist, whether more legislation is

needed, or whether self-regulation can suffice.

The marketing and information reseller industries generally have argued

that the current framework of sector-specific laws and regulations has not

left significant gaps in consumer privacy protections, citing several

reasons. First, they have stated that the list of federal and state laws

regulating uses of personal information is extensive. Second, some

industry representatives have stated that the existing legislative and

regulatory framework generally provides adequate privacy protections—

or the flexibility to address such protections—in relation to new

technologies.

70

69

Federal Trade Commission, Paper, Plastic or Mobile? An FTC Workshop on Mobile

Payments (Washington, D.C.: March 2013).

For example, they have noted that the FTC Act grants

FTC broad authority that can apply to a range of circumstances and

technologies—as with the enforcement actions discussed earlier to

address alleged misrepresentations of a company’s privacy policy

involving web tracking and history sniffing. Third, a representative of one