Step'by-step guide to critiquing

research. Part 1: quantitative research

Michaei Coughian, Patricia Cronin, Frances Ryan

Abstract

When caring for patients it is essential that nurses are using the

current best practice. To determine what this is, nurses must be able

to read research critically. But for many qualified and student nurses

the terminology used in research can be difficult to understand

thus making critical reading even more daunting. It is imperative

in nursing that care has its foundations in sound research and it is

essential that all nurses have the ability to critically appraise research

to identify what is best practice. This article is a step-by step-approach

to critiquing quantitative research to help nurses demystify the

process and decode the terminology.

Key words: Quantitative research

methodologies

Review process • Research

]or many qualified nurses and nursing students

research is research, and it is often quite difficult

to grasp what others are referring to when they

discuss the limitations and or strengths within

a research study. Research texts and journals refer to

critiquing the literature, critical analysis, reviewing the

literature, evaluation and appraisal of the literature which

are in essence the same thing (Bassett and Bassett, 2003).

Terminology in research can be confusing for the novice

research reader where a term like 'random' refers to an

organized manner of selecting items or participants, and the

word 'significance' is applied to a degree of chance. Thus

the aim of this article is to take a step-by-step approach to

critiquing research in an attempt to help nurses demystify

the process and decode the terminology.

When caring for patients it is essential that nurses are

using the current best practice. To determine what this is

nurses must be able to read research. The adage 'All that

glitters is not gold' is also true in research. Not all research

is of the same quality or of a high standard and therefore

nurses should not simply take research at face value simply

because it has been published (Cullum and Droogan, 1999;

Rolit and Beck, 2006). Critiquing is a systematic method of

Michael Coughlan, Patricia Cronin and Frances Ryan are Lecturers,

School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Dubhn, Trinity

College, Dublin

Accepted for

publication:

March 2007

appraising the strengths and limitations of a piece of research

in order to determine its credibility and/or its applicability

to practice (Valente, 2003). Seeking only limitations in a

study is criticism and critiquing and criticism are not the

same (Burns and Grove, 1997). A critique is an impersonal

evaluation of the strengths and limitations of the research

being reviewed and should not be seen as a disparagement

of the researchers ability. Neither should it be regarded as

a jousting match between the researcher and the reviewer.

Burns and Grove (1999) call this an 'intellectual critique'

in that it is not the creator but the creation that is being

evaluated. The reviewer maintains objectivity throughout

the critique. No personal views are expressed by the

reviewer and the strengths and/or limitations of the study

and the imphcations of these are highlighted with reference

to research texts or journals. It is also important to remember

that research works within the realms of probability where

nothing is absolutely certain. It is therefore important to

refer to the apparent strengths, limitations and findings

of a piece of research (Burns and Grove, 1997). The use

of personal pronouns is also avoided in order that an

appearance of objectivity can be maintained.

Credibility and integrity

There are numerous tools available to help both novice and

advanced reviewers to critique research studies (Tanner,

2003).

These tools generally ask questions that can help the

reviewer to determine the degree to which the steps in the

research process were followed. However, some steps are

more important than others and very few tools acknowledge

this.

Ryan-Wenger (1992) suggests that questions in a

critiquing tool can be subdivided in those that are useful

for getting a feel for the study being presented which she

calls 'credibility variables' and those that are essential for

evaluating the research process called 'integrity variables'.

Credibility variables concentrate on how believable the

work appears and focus on the researcher's qualifications and

ability to undertake and accurately present the study. The

answers to these questions are important when critiquing

a piece of research as they can offer the reader an insight

into \vhat to expect in the remainder of the study.

However, the reader should be aware that identified strengths

and limitations within this section will not necessarily

correspond with what will be found in the rest of the work.

Integrity questions, on the other hand, are interested in the

robustness of the research method, seeking to identify how

appropriately and accurately the researcher followed the

steps in the research

process.

The answers to these questions

658

British Journal of Nursing.

2007.

Vol 16, No II

RESEARCH METHODOLOGIES

Table

1.

Research questions

-

guidelines

for

critiquing

a

quantitative research study

Elements influencing

the

beiievabiiity

of the

research

Elements

Writing styie

Author

Report titie

Abstract

Questions

Is

the

report well written

-

concise, grammatically correct, avoid

the use of

jargon?

Is it

weil iaid

out and

organized?

Do

the

researcher(s') quaiifications/position indicate

a

degree

of

knowledge

in

this particuiar field?

Is

the

title clear, accurate

and

unambiguous?

Does

the

abstract offer

a

clear overview

of

the study including

the

research problem, sample,

methodology, finding

and

recommendations?

Elements influencing

the

robustness

of the

research

Elements

Purpose/research

Problem

Logical consistency

Literature review

Theoreticai framework

Aims/objectives/

research question/

hypotheses

Sampie

Ethicai considerations

Operational definitions

Methodology

Data Anaiysis

/

results

Discussion

References

Questions

Is

the

purpose

of

the study/research problem clearly identified?

Does

the

research report foilow

the

steps

of

the research process

in a

iogical manner? Do these steps

naturally fiow

and are the

iinks ciear?

is

the

review Iogicaily organized? Does

it

offer

a

balanced critical anaiysis

of

the iiterature?

is the

majority

of the literature

of

recent origin?

is it

mainly from primary sources

and of

an empirical nature?

Has

a

conceptual

or

theoretical framework been identified?

Is the

framework adequately described?

is

the

framework appropriate?

Have alms

and

objectives,

a

research question

or

hypothesis been identified? If so

are

they clearly

stated? Do they reflect

the

information presented

in the

iiterature review?

Has

the

target popuiation been cieariy identified? How were

the

sample selected? Was

it a

probability

or non-probabiiity sampie?

is it of

adequate size? Are

the

indusion/exciusion criteria dearly identified?

Were

the

participants fuiiy informed about

the

nature

of

the research? Was

the

autonomy/

confidentiaiity

of

the participants guaranteed? Were

the

participants protected from harm? Was ethicai

permission granted

for the

study?

Are aii

the

terms, theories

and

concepts mentioned

in the

study dearly defined?

is

the

research design cieariy identified? Has

the

data gathering instrument been described?

is the

instrument appropriate? How was

it

deveioped? Were reliabiiity and validity testing undertaken

and the

resuits discussed? Was

a

piiot study undertaken?

What type

of

data

and

statisticai analysis

was

undertaken? Was

it

appropriate? How many

of

the sampie

participated? Significance

of

the findings?

Are

the

findings iinked back

to the

iiterature review?

if a

hypothesis was identified

was it

supported?

Were

the

strengths

and

limitations

of

the study including generalizability discussed? Was

a

recommendation

for

further research made?

Were ali

the

books, journais

and

other media aliuded

to in the

study accurateiy referenced?

will help to identify the trustworthiness of the study and its

applicability to nursing practice.

Critiquing the research steps

In critiquing the steps in the research process a number

of questions need to be asked. However, these questions

are seeking more than a simple 'yes' or 'no' answer. The

questions are posed to stimulate the reviewer to consider

the implications of what the researcher has done. Does the

way a step has been applied appear to add to the strength

of the study or does it appear as a possible limitation to

implementation of the study's findings?

{Table

1).

Eiements influencing beiievabiiity

of

the study

Writing style

Research reports should be well written, grammatically

correct, concise and well organized.The use of jargon should

be avoided where possible. The style should be such that it

attracts the reader to read on (Polit and Beck, 2006).

Author(s)

The author(s') qualifications and job title can be a useful

indicator into the researcher(s') knowledge of the area

under investigation and ability to ask the appropriate

questions (Conkin Dale, 2005). Conversely a research

study should be evaluated on its own merits and not

assumed to be valid and reliable simply based on the

author(s') qualifications.

Report title

The title should be between 10 and 15 words long and

should clearly identify for the reader the purpose of the

study (Connell Meehan, 1999). Titles that are too long or

too short can be confusing or misleading (Parahoo, 2006).

Abstract

The abstract should provide a succinct overview of the

research and should include information regarding the

purpose of the study, method, sample size and selection.

Hritislijourn.il

of

Nursing.

2007.

Vol 16.

No 11

659

the main findings

and

conclusions

and

recommendations

(Conkin Dale, 2005). From

the

abstract

the

reader should

be able

to

determine

if

the study

is

of interest and whether

or

not to

continue reading (Parahoo, 2006).

Eiements influencing robustness

Purpose

of

the study/research problem

A research problem

is

often first presented

to the

reader

in

the introduction

to the

study (Bassett

and

Bassett, 2003).

Depending

on

what is

to be

investigated some authors will

refer

to it as the

purpose

of

the study.

In

either case

the

statement should at least broadly indicate

to

the reader what

is

to be

studied (Polit and Beck, 2006). Broad problems are

often multi-faceted and will need

to

become narrower and

more focused before they

can be

researched.

In

this

the

literature review can play

a

major role (Parahoo, 2006).

Logical consistency

A research study needs

to

follow the steps

in

the process

in

a

logical manner.There should also be a clear link between the

steps beginning with the purpose of the study and following

through the literature review, the theoretical framework, the

research question, the methodology section, the data analysis,

and

the

findings (Ryan-Wenger, 1992).

Literature review

The primary purpose

of

the literature review

is to

define

or develop

the

research question while also identifying

an appropriate method

of

data collection (Burns

and

Grove, 1997).

It

should also help

to

identify

any

gaps

in

the literature relating

to the

problem

and to

suggest

how

those gaps might

be

filled.

The

literature review should

demonstrate

an

appropriate depth

and

breadth

of

reading

around

the

topic

in

question.

The

majority

of

studies

included should

be of

recent origin

and

ideally less than

five years old. However, there

may be

exceptions

to

this,

for example,

in

areas where there

is a

lack

of

research,

or a

seminal or all-important piece of work that is still relevant to

current practice.

It is

important also that

the

review should

include some historical

as

well

as

contemporary material

in order

to put the

subject being studied into context. The

depth

of

coverage will depend

on the

nature

of

the subject,

for example, for

a

subject with a vast range of literature then

the review will need

to

concentrate

on a

very specific area

(Carnwell, 1997). Another important consideration

is the

type

and

source

of

hterature presented. Primary empirical

data from

the

original source

is

more favourable than

a

secondary source

or

anecdotal information where

the

author relies

on

personal evidence

or

opinion that

is not

founded

on

research.

A good review usually begins with an introduction which

identifies

the key

words used

to

conduct

the

search

and

information about which databases were used. The themes

that emerged from

the

literature should then

be

presented

and discussed (Carnwell, 1997).

In

presenting previous

work

it is

important that

the

data

is

reviewed critically,

highlighting both

the

strengths and limitations

of

the study.

It should also

be

compared and contrasted with

the

findings

of other studies (Burns and Grove, 1997).

Theoretical framework

Following

the

identification

of the

research problem

and

the

review

of the

literature

the

researcher should

present

the

theoretical framework (Bassett

and

Bassett,

2003).

Theoretical frameworks

are a

concept that novice

and experienced researchers find confusing.

It is

initially

important

to

note that not all research studies use

a

defined

theoretical framework (Robson, 2002).

A

theoretical

framework

can be a

conceptual model that

is

used

as a

guide

for the

study (Conkin Dale, 2005)

or

themes from

the literature that are conceptually mapped and used

to set

boundaries

for the

research (Miles

and

Huberman, 1994).

A sound framework also identifies

the

various concepts

being studied

and the

relationship between those concepts

(Burns

and

Grove, 1997). Such relationships should have

been identified

in the

literature. The research study should

then build

on

this theory through empirical observation.

Some theoretical frameworks

may

include

a

hypothesis.

Theoretical frameworks tend

to be

better developed

in

experimental

and

quasi-experimental studies

and

often

poorly developed

or

non-existent

in

descriptive studies

(Burns and Grove, 1999).The theoretical framework should

be clearly identified and explained

to the

reader.

Aims and objectives/research question/

research hypothesis

The purpose of the aims and objectives of a study, the research

question and the research hypothesis is to form a link between

the initially stated purpose

of

the study

or

research problem

and

how the

study will

be

undertaken (Burns

and

Grove,

1999).

They should

be

clearly stated

and be

congruent with

the data presented

in the

literature review. The

use of

these

items

is

dependent

on the

type

of

research being performed.

Some descriptive studies may

not

identify any

of

these items

but simply refer

to the

purpose

of

the study

or the

research

problem, others will include either aims

and

objectives

or

research questions (Burns

and

Grove, 1999). Correlational

designs, study

the

relationships that exist between

two or

more variables and accordingly use either a research question

or hypothesis. Experimental

and

quasi-experimental studies

should clearly state

a

hypothesis identifying

the

variables

to

be manipulated, the population that

is

being studied

and the

predicted outcome (Burns and Grove, 1999).

Sample

and

sample size

The degree

to

which

a

sample reflects

the

population

it

was drawn from

is

known

as

representativeness

and in

quantitative research this

is a

decisive factor

in

determining

the adequacy

of

a study (Polit

and

Beck, 2006).

In

order

to select

a

sample that

is

likely

to be

representative

and

thus identify findings that

are

probably generalizable

to

the target population

a

probability sample should

be

used

(Parahoo,

2006).

The size

of

the sample

is

also important

in

quantitative research

as

small samples

are at

risk

of

being

overly representative

of

small subgroups within

the

target

population. For example,

if, in a

sample of general nurses,

it

was noticed that 40%

of

the respondents were males, then

males would appear

to be

over represented

in the

sample,

thereby creating

a

sampling error.

The

risk

of

sampling

660

Britishjournal

of

Nursing.

2007.

Vol 16. No

II

RESEARCH METHODOLOGIES

errors decrease

as

larger sample sizes

are

used (Burns

and

Grove, 1997).

In

selecting

the

sample

the

researcher should

clearly identify

who the

target population

are and

what

criteria were used

to

include

or

exclude participants.

It

should also

be

evident

how the

sample

was

selected

and

how many were invited

to

participate (Russell, 2005).

Ethical considerations

Beauchamp

and

Childress (2001) identify four fundamental

moral principles: autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence

and

justice.

Autonomy infers that

an

individual

has

the

right

to freely decide

to

participate

in a

research study without

fear

of

coercion

and

with

a

full knowledge

of

what

is

being

investigated. Non-maleficence imphes

an

intention

of not

harming

and

preventing harm occurring

to

participants

both

of a

physical

and

psychological nature (Parahoo,

2006).

Beneficence

is

interpreted

as the

research benefiting

the participant

and

society

as a

whole (Beauchamp

and

Childress, 2001). Justice

is

concerned with

all

participants

being treated

as

equals

and no one

group

of

individuals

receiving preferential treatment because,

for

example,

of

their position

in

society (Parahoo, 2006). Beauchamp

and

Childress (2001) also identify four moral rules that

are

both

closely connected

to

each other

and

with

the

principle

of

autonomy. They

are

veracity (truthfulness), fidelity (loyalty

and trust), confidentiality and privacy.The latter pair are often

linked

and

imply that

the

researcher has

a

duty

to

respect

the

confidentiality and/or

the

anonymity

of

participants

and

non-participating subjects.

Ethical committees

or

institutional review boards have

to

give approval before research

can be

undertaken. Their role

is

to

determine that ethical principles

are

being applied

and

that

the

rights

of

the individual

are

being adhered

to

(Burns

and Grove, 1999).

Operational definitions

In

a

research study

the

researcher needs

to

ensure that

the reader understands what

is

meant

by the

terms

and

concepts that

are

used

in the

research. To ensure this

any

concepts

or

terms referred

to

should

be

clearly defined

(Parahoo, 2006).

Methodology: research design

Methodology refers

to the

nuts

and

bolts

of how a

research study

is

undertaken. There

are a

number

of

important elements that need

to be

referred

to

here

and

the first

of

these

is the

research design. There

are

several

types

of

quantitative studies that

can be

structured under

the headings

of

true experimental, quasi-experimental

and non-experimental designs (Robson, 2002)

{Table

2).

Although

it is

outside

the

remit

of

this article, within each

of these categories there

are a

range

of

designs that will

impact

on

how

the

data collection

and

data analysis phases

of

the

study

are

undertaken. However, Robson (2002)

states these designs

are

similar

in

many respects

as

most

are concerned with patterns

of

group behaviour, averages,

tendencies

and

properties.

Methodology: data collection

The next element

to

consider after

the

research design

is

the

data collection method.

In a

quantitative study

any

number

of

strategies

can be

adopted when collecting data

and these

can

include interviews, questionnaires, attitude

scales

or

observational tools. Questionnaires

are the

most

commonly used data gathering instruments

and

consist

mainly

of

closed questions with

a

choice

of

fixed answers.

Postal questionnaires

are

administered

via

the

mail

and

have

the value of perceived anonymity. Questionnaires

can

also

be

administered

in

face-to-face interviews

or in

some instances

over

the

telephone (Polit

and

Beck, 2006).

Methodology: instrument design

After identifying

the

appropriate data gathering method

the next step that needs

to be

considered

is the

design

of

the

instrument. Researchers have

the

choice

of

using

a previously designed instrument

or

developing

one for

the study

and

this choice should

be

clearly declared

for

the reader. Designing

an

instrument

is a

protracted

and

sometimes difficult process (Burns

and

Grove, 1997)

but the

overall

aim is

that

the

final questions will

be

clearly linked

to

the

research questions

and

will elicit accurate information

and will help achieve

the

goals

of

the

research.This, however,

needs

to be

demonstrated

by

the

researcher.

Table

2.

Research designs

Design

Experimental

Qucisl-experimental

Non-experimental,

e.g.

descriptive

and

Includes: cross-sectional.

correlationai.

comparative.

iongitudinal studies

Sample

2

or

more groups

One

or

more groups

One

or

more groups

Sample

allocation

Random

Random

Not applicable

Features

• Groups

get

different treatments

•

One

variable

has

not

been manipuiated

or

controlled (usually

because

it

cannot

be)

• Discover

new

meaning

• Describe what already

exists

• Measure

the

relationship

between

two

or

more

variables

Outcome

• Cause and effiect relationship

• Cause and effect relationship

but iess powerful than

experimental

• Possible hypothesis

for

future research

• Tentative explanations

Britishjournal

of

Nursing.

2007.

Vol 16.

No

11

661

If

a

previously designed instrument

is

selected the researcher

should clearly establish that chosen instrument

is the

most

appropriate.This is achieved by outlining how the instrument

has measured

the

concepts under study. Previously designed

instruments

are

often

in the

form

of

standardized tests

or scales that have been developed

for the

purpose

of

measuring

a

range

of

views, perceptions, attitudes, opinions

or even abilities. There

are a

multitude

of

tests

and

scales

available, therefore

the

researcher

is

expected

to

provide

the

appropriate evidence

in

relation

to

the

validity and reliability

of the instrument (Polit and Beck, 2006).

Methodology: validity

and

reliability

One

of

the

most important features

of

any instrument

is

that

it

measures the concept being studied

in an

unwavering

and consistent way. These

are

addressed under

the

broad

headings

of

validity

and

reliability respectively.

In

general,

validity

is

described

as the

ability

of the

instrument

to

measure what

it is

supposed

to

measure

and

reliability

the

instrument's ability

to

consistently

and

accurately measure

the concept under study (Wood

et

al,

2006).

For the

most

part,

if

a

well established

'off

the shelf instrument has been

used

and not

adapted

in

any way, the validity

and

reliability

will have been determined already

and the

researcher

should outline what this

is.

However,

if the

instrument

has been adapted

in any

way

or is

being used

for a new

population then previous validity

and

reliability will

not

apply.

In

these circumstances

the

researcher should indicate

how

the

reliability

and

validity

of

the adapted instrument

was established (Polit

and

Beck, 2006).

To establish

if the

chosen instrument

is

clear

and

unambiguous

and to

ensure that

the

proposed study

has

been conceptually well planned

a

mini-version

of

the main

study, referred to as a pilot study, should be undertaken before

the main study. Samples used

in

the

pilot study are generally

omitted from

the

main study. Following

the

pilot study

the

researcher may adjust definitions, alter

the

research question,

address changes

to the

measuring instrument

or

even alter

the sampling strategy.

Having described the research design, the researcher should

outline

in

clear, logical steps

the

process

by

which

the

data

was collected. All steps should

be

fully described

and

easy

to

follow (Russell, 2005).

Analysis

and

results

Data analysis

in

quantitative research studies

is

often seen

as

a

daunting process. Much

of

this

is

associated with

apparently complex language

and the

notion

of

statistical

tests.

The researcher should clearly identify what statistical

tests were undertaken,

why

these tests were used

and

what •were

the

results. A rule

of

thumb

is

that studies that

are descriptive

in

design only

use

descriptive statistics,

correlational studies, quasi-experimental

and

experimental

studies

use

inferential statistics.

The

latter

is

subdivided

into tests

to

measure relationships

and

differences between

variables (Clegg, 1990).

Inferential statistical tests

are

used

to

identify

if a

relationship

or

difference between variables

is

statistically

significant. Statistical significance helps

the

researcher

to

rule

out

one important threat

to

validity

and

that

is

that

the

result could

be

due

to

chance rather than

to

real differences

in

the

population. Quantitative studies usually identify

the

lowest level

of

significance

as

PsO.O5

(P =

probability)

(Clegg, 1990).

To enhance readability researchers frequently present

their findings

and

data analysis section under

the

headings

of the research questions (Russell,

2005).

This

can

help

the

reviewer determine

if

the results that

are

presented clearly

answer

the

research

questions.

Tables,

charts

and

graphs may

be used

to

summarize

the

results

and

should

be

accurate,

clearly identified

and

enhance

the

presentation

of

results

(Russell, 2005).

The percentage

of the

sample

who

participated

in

the study

is an

important element

in

considering

the

generalizability

of

the

results.

At

least fifty percent

of

the

sample

is

needed

to

participate

if

a response bias

is to be

avoided (Polit

and

Beck, 2006).

Discussion/conclusion/recommendations

The discussion

of

the findings should Oow logically from

the

data

and

should

be

related back

to

the

literature review thus

placing the study

in

context (Russell, 2002). If

the

hypothesis

was deemed

to

have been supported

by the

findings,

the researcher should develop this

in the

discussion.

If a

theoretical

or

conceptual framework

was

used

in the

study

then

the

relationship with

the

findings should

be

explored.

Any interpretations

or

inferences drawn should

be

clearly

identified as such

and

consistent with

the

results.

The significance

of the

findings should

be

stated

but

these should

be

considered within

the

overall strengths

and limitations

of

the study (Polit

and

Beck, 2006).

In

this

section some consideration should

be

given

to

whether

or

not the

findings

of

the

study were generalizable, also

referred

to

as

external validity.

Not all

studies make

a

claim

to generalizability but the researcher should have undertaken

an assessment

of

the key factors

in

the

design, sampling

and

analysis

of

the study

to

support any such claim.

Finally

the

researcher should have explored

the

clinical

significance

and

relevance

of

the

study. Applying findings

in practice should

be

suggested with caution

and

will

obviously depend

on the

nature

and

purpose

of

the study.

In addition,

the

researcher should make relevant

and

meaningful suggestions

for

future research

in the

area

(Connell Meehan, 1999).

References

The research study should conclude with

an

accurate list

of

all

the

books; journal articles, reports

and

other media

that were referred

to in the

work (Polit

and

Beck, 2006).

The referenced material

is

also

a

useful source

of

further

information

on

the

subject being studied.

Conciusions

The process

of

critiquing involves

an

in-depth examination

of each stage

of

the research process.

It

is not a

criticism

but

rather

an

impersonal scrutiny

of a

piece

of

work using

a

balanced

and

objective approach, the purpose

of

which

is to

highlight both strengths

and

weaknesses,

in

order

to

identify

662

Uritish Journal

of

Nursinii.

2007.

Vol

16.

No

II

RESEARCH METHODOLOGIES

whether a piece of research is trustworthy and unbiased. As

nursing practice is becoming increasingly more evidenced

based, it is important that care has its foundations in sound

research. It is therefore important that all nurses have the

ability to critically appraise research in order to identify what

is best practice. HH

Russell

C

(2005) Evaluating quantitative researcli reports.

Nephrol Nurs

J

32(1):

61-4

Ryan-Wenger

N

(1992) Guidelines

for

critique

of

a

research report.

Heart

Lung

21(4): 394-401

Tanner

J

(2003) Reading

and

critiquing research.

BrJ

Perioper

Nurs 13(4):

162-4

Valente

S

(2003) Research dissemination

and

utilization: Improving care

at

the bedside.J Nurs

Care Quality

18(2): 114-21

Wood

MJ,

Ross-Kerr JC, Brink

PJ

(2006)

Basic

Steps

in

Planning Nursing

Research:

From Question

to

Proposal

6th

edn.

Jones

and

Bartlett, Sudbury

Bassett

C,

B.issett

J

(2003) Reading

and

critiquing research.

BrJ

Perioper

NriK 13(4): 162-4

Beauchamp

T,

Childress

J

(2001)

Principles

of

Biomedical

Ethics.

5th edn.

O.xford University Press, Oxford

Burns

N,

Grove

S

(1997)

The

Practice

of

Nursing

Research:

Conduct,

Critique

and

Utilization.

3rd

edn.WB Saunders Company, Philadelphia

Burns

N,

Grove

S

(1999)

Understanding

Nursing

Research.

2nd

edn.

WB

Saunders Company. Philadelphia

Carnell

R

(1997) Critiquing research. Nurs

Pract

8(12): 16-21

Clegg F (1990)

Simple

Statistics: A

Course

Book for

the

Social

Sciences.

2nd

edn.

Cambridge University Press. Cambridge

Conkin DaleJ (2005) Critiquing research

for

use

in

practice.J

Pediatr Health

Care

19:

183-6

Connell Meehan

T

(1999) The research critique. In:Treacy P, Hyde A, eds.

Nursing Research

and

Design.

UCD

Press, Dublin: 57-74

Cullum

N.

Droogan

J

(1999) Using research

and the

role

of

systematic

reviews

of

the literature.

In:

Mulhall A.

Le

May A. eds.

Nursing

Research:

Dissemination

and

Implementation.

Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh:

109-23-

Miles

M,

Huberman

A

(1994)

Qualitative

Data

Analysis.

2nd

edn.

Sage,

Thousand Oaks. Ca

Parahoo

K

(2006) Nursing Research: Principles, Process

and

Issties.

2nd edn.

Palgrave Macmillan. Houndmills Basingstoke

Polit

D.

Beck

C

(2006)

Essentials

of

Nursing

Care:

Methods,

Appraisal

and

Utilization.

6th

edn. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia

Robson

C

(2002) Reat World

Research.

2nd

edn.

Blackwell Publishing,

O.xford

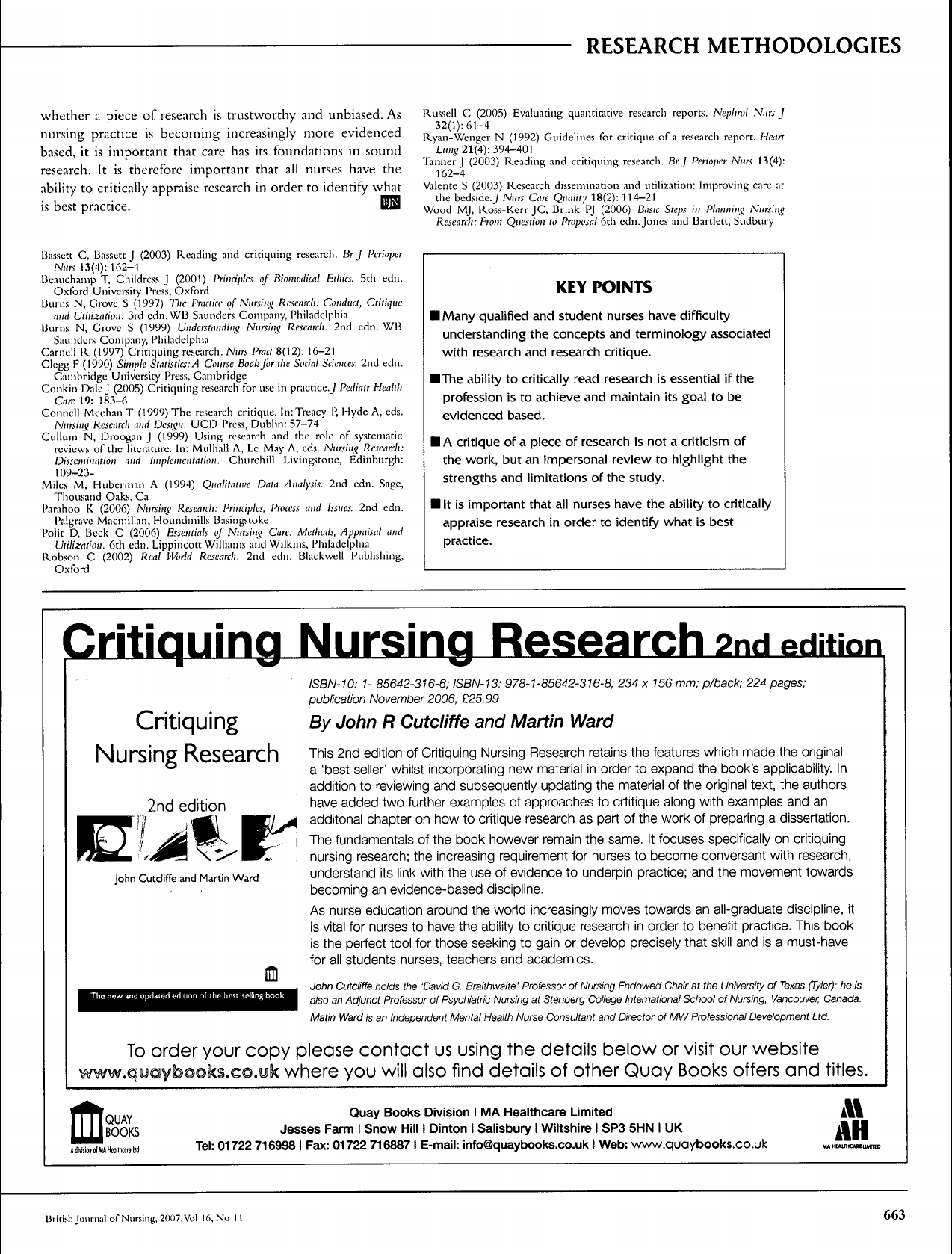

KEY POINTS

I Many qualified and student nurses have difficulty

understanding the concepts and terminology associated

with research and research critique.

IThe ability to critically read research is essential if the

profession is to achieve and maintain its goal to be

evidenced based.

IA critique of a piece of research is not a criticism of

the wori<, but an impersonai review to highlight the

strengths and iimitations of the study.

I It is important that all nurses have the ability to criticaiiy

appraise research In order to identify what is best

practice.

Critiquing Nursing Research

2nd

edition

Critiquing

Nursing Research

2nd edition

ISBN-W;

1- 85642-316-6; lSBN-13; 978-1-85642-316-8; 234

x

156 mm; p/back; 224 pages;

publicatior) November 2006; £25.99

By John

R

Cutdiffe and Martin Ward

This 2nd edition

of

Critiquing Nursing Research retains the features which made the original

a 'best seller' whilst incorporating

new

material

in

order

to

expand

the

book's applicability.

In

addition

to

reviewing and subsequently updating

the

material

of

the original text,

the

authors

have added

two

further examples

of

approaches

to

crtitique along with examples and

an

additonal chapter

on

how

to

critique research

as

part

of

the work

of

preparing

a

dissertation.

The fundamentals

of

the book however remain

the

same.

It

focuses specifically

on

critiquing

nursing research;

the

increasing requirement

for

nurses

to

become conversant with research,

understand

its

link with

the

use

of

evidence

to

underpin practice; and

the

movement towards

becoming

an

evidence-based discipline.

As nurse education around the world increasingly moves towards

an

all-graduate discipline,

it

is vital

for

nurses

to

have the ability

to

critique research

in

order

to

benefit practice. This book

is

the

perfect tool

for

those seeking

to

gain

or

develop precisely that skill

and is a

must-have

for all students nurses, teachers and academics.

John Cutclitfe holds the 'David

G.

Braithwaite' Protessor

of

Nursing

Endowed Chair at the

University

of

Texas

(Tyler);

he is

also an Adjunct Professor

of

Psychiatric

Nursing

at

Stenberg College

International

School

of

Nursing,

Vancouver,

Canada.

Matin Ward is an Independent

tvtental

Health Nurse Consultant and Director

of

tvlW Protessional

Develcpment Ltd.

To order your copy please contact us using

the

details below

or

visit our website

www.quaybooks.co.yk where you will also tind details

ot

other Quay Books otters and titles.

John Cutcliffe and Martin Ward

I

QUAY

BOOKS

AdMsioiiDftUHiolthcareM

Quay Books Division

I

MA

Healthcare Limited

Jesses Farm

I

Snow Hill

I

Dinton

I

Salisbury

I

Wiltshire

I

SP3

5HN

I

UK

Tel:

01722 716998

I

Fax: 01722 716887

I

E-mail: [email protected]k

I

Web: www.quaybooks.co.uk

A\

ilH

MAHbUTHCASIUMITED

Uritishjoiirnnl

of

Nursinji;. 2OO7.V0I 16.

No

11

663