PROJECT REPORT

ASCERTAINMENT OF THE

ESTIMATED EXCESS MORTALITY FROM

HURRICANE MARÍA IN PUERTO RICO

IN COLLABORATION WITH THE UNIVERSITY OF

PUERTO RICO GRADUATE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH

Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico

AC

KNOWLEDGMENTS

This project and the creation of this report would not have been possible without the

support of various institutions, agencies and individuals. We would like to

acknowledge the support from the GW Office of the Vice Provost for Research and the

ITS staff who helped us create a secure platform to store our data. We also thank them

for their assistance in establishing the needed institutional agreements. A special

thanks goes to our external panel of experts and internal technical specialists who

reviewed the methods design and provided input on this report (see Annex 2 for a

complete list of panelists).

We thank the Milken Institute School of Public Health for providing administrative

and financial support at the beginning and throughout the study, specially the

Executive Dean for Finance and Administration Gordon Taylor. We want to thank the

then acting Associate Dean for Research Melissa Perry, who took the risk with us, and

the ITS team of the school, Regina Scriven and Joseph Creech. We are also grateful

for the support of Dean Dharma Vázquez of the University of Puerto Rico Graduate

School of Public Health and all of those who provided their help.

This project was supported by the dedication of the personnel of key institutions

in Puerto Rico who provided team members with mortality information, and most

importantly, for helping us to understand their work processes. We acknowledge the

support of the Demographic Registry and particularly Dr. María Juiz Gallego and José

López Rodriguez. At the Bureau of Forensic Sciences, we thank Monica Menendez and

her staff for continued support. The project team is grateful to Dr. Mario Marrazzi at

the Puerto Rico Institute of Statistics who provided us with information and data for

establishing counterfactuals. From the Puerto Rico Planning Board (Junta de

Planificación), Alejandro Díaz Marrero and his colleague Maggie Perez Guzmán

provided information on the travel surveys. We thank Dr. Istoni Da Luz Sant’Ana and

Dr. Israel Almodóvar for their advice on R programming.

We would like to thank Martie Sucec for editing the report, Cynthia Gorostiaga and

Enrique Rivera Torres and the team at the Rivera Group for translation and Kate

Connolly for designing the report.

We would also like to recognize the efforts of the following GW SPH graduate

students whose literature reviews and other work helped support project activities:

Cosette Audi, Lorena Segarra, Courtney Irwin, Paige Craig, Connor Skelton and

Nicolette Bestul.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF ACRONYMS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

METHODS

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

INTRODUCTION

MORTALITY

METHODS

FINDINGS

RECOMMENDATIONS

COMMUNICATIONS

METHODS

FINDINGS

RECOMMENDATIONS

References

Annex 1

Annex 2

Annex 3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

i

i

ii

1

3

4

8

16

22

22

25

35

40

1

6

9

Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico

ASPR – Ofce of the Assistant Secretary for

Preparedness and Response

BFS – Puerto Rico Bureau of Forensic Sciences

BTS – U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics

CDC – Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CERC – Crisis Emergency Risk Communication

COE – Center for Operations in Emergencies

COOP – Continuation of Operations

DHHS – Department of Health and Human Services

DoH – Puerto Rico Department of Health

DPS – Puerto Rico Department of Public Safety

EMB – Puerto Rico Emergency Management Bureau

FEMA – Federal Emergency Management Agency

GAM – General Additive Model

GLM – Generalized Linear Model

GW SPH – The George Washington University

Milken Institute School of Public Health

IRB – Institutional Review Board

NCHS – National Center for Health Statistics

NGO – Non-Governmental Organization

NIMS – FEMA National Incidence

Management System

NPS – National Planning Scenario

PR – Puerto Rico

PRVSR – Puerto Rico Vital Statistics Registry

PRVSS – Puerto Rico Vital Statistics System

UPR GSPH – University of Puerto Rico

Graduate School of Public Health

WHO – World Health Organization

List of Acronyms

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In order to accurately estimate the excess number

of deaths due to Hurricane María, the Governor

of Puerto Rico sought an independent assessment

of mortality and commissioned The George

Washington University Milken Institute School of

Public Health (GW SPH) to complete the assessment.

The project had the following objectives:

1) assess the excess total mortality adjusting for

demographic variables and seasonality, report a

point estimate and condence interval and make

recommendations; 2) evaluate the implementation

of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

guidelines for mortality reporting in disasters and

identify areas of opportunity for improvement;

and 3) assess crisis and mortality communication

plans and actions by the government as well as

understand experiences and perceptions of key

participant groups to make recommendations based

on communications best practices.

METHODS

We implemented the project as three studies, each

with specific yet complementary methodologies.

Our excess mortality study analyzed past mortality

patterns (mortality registration and population

census data from 2010 to 2017) in order to predict

the expected mortality if Hurricane María had not

occurred (predicted mortality) and compare this

figure to the actual deaths that occurred (observed

mortality). The difference between those two

numbers is the estimate of excess mortality

due to the hurricane. We developed a series of

generalized linear models (GLMs) with monthly data

for the pre-hurricane period of July 2010-August

2017, accounting for trends in population size

and distribution over this period in terms of age,

sex, seasonality and residence by municipal level

of socioeconomic development. Our estimates

also considered Puerto Rico’s consistently high

emigration during the prior decade and dramatic

population displacement after the hurricane. We

used the model results to project forward mortality

that would have been expected if the hurricane had

not occurred for two scenarios—if the population

had not changed (census scenario), and explicitly

accounting for massive post-hurricane population

displacement from the island (displacement

scenario). For observed mortality, we used

records for all deaths occurring from September

2017-February 2018, provided by the Puerto Rico

Vital Statistics Records (PRVSR) division of the Puerto

Rico Department of Health (DoH). The estimates

of excess all-cause mortality attributable to the

hurricane are the result of comparing the projections

for the census and displacement scenarios to

observed mortality in the vital registration data.

In order to respond to the Puerto Rican

Government’s query about how well CDC guidelines

for mortality reporting in a disaster were followed,

we conducted a two-part study to assess both the

death certication process and the quality of death

certicate data. We conducted interviews with 26

individuals involved in the death certication and

registration process to understand procedures under

normal conditions and whether and how these were

affected after the hurricane. In addition, we reviewed

legislation and manuals related to death certication

in Puerto Rico, as well as literature on death

certication in general and specically in disasters.

With respect to quality of the death certicates

i

Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico

and coding for causes of death, we consulted the

relevant scientic literature. We conducted a series

of checks on the mortality dataset, assessing it for

completeness, timeliness, internal consistency

and the quality of cause of death reporting by

evaluating garbage codes, or mis-assignments,

in the underlying cause of death.

Our third study assessed crisis and emergency risk

communications by the Government of Puerto Rico

before and after Hurricane María, with an emphasis

on the communications plans in place at the time

of the hurricane, trained staff dedicated to crisis

and emergency risk communication, procedures

for mortality reporting to the public, spokespeople

interaction with the media and key participant

perceptions of the government’s risk communication

and mortality reporting. For the communication

assessment methodology, instruments, and analytical

framework, we applied established guidelines from

CDC and the World Health Organization (WHO) for

communication in emergencies, which are supported

by a robust scientic evidence base. We also applied

principles from the Federal Emergency Management

Agency (FEMA) Whole Community Approach for

community-based emergency preparedness (FEMA

2011). We interviewed 11 Puerto Rico Government

agency leadership and communications personnel

in order to understand: crisis and emergency risk

communication plans, processes and interagency

coordination for the preparation, approval and

dissemination of information to the public; their

experiences related to communications before and

after Hurricane María; and recommendations for

future communications in emergency situations.

We also interviewed 22 key leaders from different

communities in Puerto Rico, representing diverse

stakeholder groups including municipal mayors,

community and faith leaders, emergency responders,

police, non-prot organization personnel, health care

providers and funeral directors. In order to formulate

recommendations for future communications,

these interviews focused on understanding

stakeholder experiences from Hurricane María,

community involvement in disaster communications

planning and perceptions of the government’s risk

communication and mortality reporting.

To assess the post-hurricane information environment,

we reviewed 17 press releases and 20 press

conferences from September 20, 2017-February

28, 2018 to evaluate information content and

spokespeople performance, and to determine the

extent to which trustworthiness, credibility and

accountability were conveyed according to CDC and

WHO guidelines. Finally, we analyzed 172 media

coverage items from major English- and Spanish-

language news outlets during the same time period,

as well as related social media commentary, to

identify factors that may have contributed to public

concerns about mortality reporting, including: reasons

and timing of mortality data reporting; contradictory

information from spokespeople and alternative

sources; information gaps; and perceptions of

the accuracy and transparency of the Puerto Rico

Government’s mortality reports.

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

Excess mortality estimation

We estimate that in mid-September 2017 there

were 3,327,917 inhabitants and in mid-February

2018 there were 3,048,173 inhabitants of Puerto

Rico, representing a population reduction by

approximately 8%. We factored this into the

migration “displacement scenario” and compared

it with a “census scenario,” which assumed no

displacement from migration in the hurricane’s

aftermath. We found that, historically, mortality

slowly decreased until August 2017, and that rates

increased for the period of September 2017 through

February 2018, with the most dramatic increase

shown in the displacement scenario accounting for

post-hurricane migration.

a)

ii

The results of our analysis of total excess mortality

by socio-demographic subgroups show that every

social stratum and age group was affected by excess

mortality. However, the impact differed by age and

socioeconomic status. The risk of death was 45%

higher and persistent until the end of the study

period for populations living in low socioeconomic

development municipalities, and older males (65+)

experienced continuous elevated risk of death

through February. Overall, we estimate that 40%

of municipalities experienced signicantly higher

mortality in the study period than in the comparable

period of the previous two years.

We conclude that excess mortality is a good indicator

for impact monitoring during and in the aftermath

of a disaster.

Death certication process

evaluation

Our study shows that physician lack of awareness

of appropriate death certication practices after

a natural disaster and the Government of Puerto

Rico’s lack of communication about death certicate

reporting prior to the 2017 hurricane season limited

the count of deaths that were reported as related to

Hurricane María. Individuals authorized to complete

death certicates include physicians and forensic

physicians; however, most physicians receive no

formal training in death certicate completion, in

particular in a disaster. When asked about the CDC

guidelines the PRVSR circulated after the hurricane

b)

Total excess mortality post-hurricane using the

migration displacement scenario is estimated to

be 2,975 (95% CI: 2,658-3,290) for the total study

period of September 2017 through February 2018.

that recommended physicians ll out a section in the

death certicate with information or other conditions

that contributed to the death, interview respondents

indicated lingering confusion about the guidelines,

while others expressed reluctance to relate deaths to

hurricanes due to concern about the subjectivity of

this determination and about liability.

The PRVSR ofces sustained damage and did not

have power to operate for some time after the

hurricane, and death registration was delayed.

Nevertheless, based on our ndings in the

assessment of death certication quality, the disaster

does not appear to have affected the completeness

of the certicates. For this assessment we compared

Puerto Rico Vital Statistics System (PRVSS) data from

September to December 2017 with the same period

in 2015 and 2016 and found that completeness of

death certicates was high with respect to age and

sex, two indicators widely used to assess this aspect

of mortality registration quality. On timeliness, there

was a statistically signicant delay in the number

of days between date of death and date of death

registration, with an average of 17 days in the period

after the hurricane compared to 12 days in the prior

year. Overall, there was a low percentage of garbage

codes as the underlying cause of death and there

appears to be no impact from the event on the

percentage of codes that were mis-assigned. With

respect to internal consistency, less than 1% of death

certicates had medically inconsistent diagnoses in

the underlying cause of death.

iii

Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico

Assessment of Crisis and

Mortality Communications and

the Information Environment

According to interviews with Puerto Rico

Government agency personnel, at the time of the

hurricane, neither the Department of Public Safety

(DPS) nor the Central Communications Ofce in the

Governor’s Ofce had written crisis and emergency

risk communication plans in place. The DoH’s Ofce

of Emergency Preparedness and Response had an

outdated emergency plan, including annexes for

Risk Communication in Emergencies and Mass

Fatality Management. Agency emergency plans

that were in place were not designed for greater

than Category 1 hurricanes, and risk messages

conveyed to the public in preparedness campaigns

were reported by key leaders to inadequately

prepare communities for a catastrophic disaster. Key

leader interview respondents also noted limited

engagement of community stakeholders in strategic

communication preparedness planning. Regardless,

key leader interview participants described

numerous strategic preparedness activities

undertaken at the local level that they believed

to minimize injuries and loss of life, especially for

vulnerable populations.

According to Puerto Rico Government agency

interviews, there were insufcient communication

personnel at the time of the hurricane, and surge

stafng was not adequately mobilized post-

hurricane. Respondents reported a lack of formalized

personnel structure for emergency communication

functions, resulting in inadequate personnel and

spokespeople training in crisis and emergency

risk communication, deciencies in coordination

of communication between central and municipal

governments and between central and federal

government counterparts. Puerto Rico Government

agency leadership interview respondents did not

identify formalized protocols for the coordination

and clearance of mortality reporting between the

DPS and the DoH at the time of the hurricane.

Puerto Rico Government personnel and

key leader interview respondents indicated

that communication contingency plans

were not in place to anticipate multiple

cascading failures of critical infrastructure

and key resource sectors. Consequently, the

central government was not prepared to

use alternative communication channels for

health-related and mortality surveillance,

public health information dissemination and

coordination with communities, including

radio and interpersonal communication.

This contributed to delayed information

availability, gaps in information and the

dissemination of inconsistent information to

the public. Furthermore, there were gaps in the

information provided by the Government of

Puerto Rico, including limited explanation of

the death certication process, distinguishing

between direct and indirect deaths, or

explanations of barriers to timely mortality

reporting. Despite the potential for information

gaps to increase the risk of the propagation of

misinformation and rumors, the Government

of Puerto Rico did not systematically monitor

and address misinformation or rumors in

news outlets and on social media platforms.

Efforts undertaken by outside groups to ll

information gaps and identify hurricane-related

deaths added to conicting mortality reports in

the information environment.

c)

iv

Key leader interview respondents perceived the

death count to be much higher, and held viewpoints

that government leadership was disconnected from

the realities of Puerto Rican communities, that there

was not transparency in reporting, that information

was intentionally withheld to evade blame and that

adequate systems were not in place to track the

death count.

Our research identied the implementation of

public information campaigns prior to the hurricane

with public health and safety messages, but the

messages did not adequately prepare Puerto Rican

communities for a catastrophic natural disaster.

There was limited community and stakeholder

engagement in disaster communication planning,

and ineffective communication contingency plans in

place, resulting in limited public health and safety

information reaching local communities post-

hurricane and alternative communication channels

that were not systematically utilized for disease

surveillance and information dissemination.

The inadequate preparedness and personnel training

for crisis and emergency risk communication, combined

with numerous barriers to accurate, timely information

and factors that increased rumor generation, ultimately

decreased the perceived transparency and credibility of

the Government of Puerto Rico.

v

Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico

RECOMMENDATIONS

OVERALL POLICY GOAL FOR MORTALITY SURVEILLANCE AND

COMMUNICATIONS

To assure the capacity of mortality surveillance and crisis and emergency

risk communication during natural disasters in Puerto Rico to support

policies and interventions that protect life and health

RECOMMENDATIONS ON MORTALITY

SURVEILLANCE FOR NATURAL DISASTERS

I. Strategic Objectives

To have a reliable and resilient institutional mortality surveillance process that provides

trustworthy and accurate evidence during natural disasters to: Establish the magnitude

of the impact of the disaster, identify areas and groups of highest risk, monitor the

performance of public health protection and prevention, and inform policy-making

and program implementation. These principles are recommended:

Readiness, establish a routine process

Rigorous, based on valid methods

Timeliness, delivering on time

Common good, having as a priority the welfare of all

II. Programmatic Recommendations for Natural Disaster

Mortality Ascertainment

Development of an Organizational Agenda

Develop a federal and Puerto Rico policy architecture for preparedness and response

to major emergencies and natural disasters.

Establish clear leadership of the DoH on mortality surveillance and capacity building

of medical personnel on death certication.

vi

Assure complete stafng and professional capacity for the PRVSR and the Bureau

of Forensic Sciences (BFS).

Review the legal framework for DoH accountability, for medical facilities and

physician assurance on death certication.

Secure needed nancial resources and reliable infrastructure with federal

government support.

Establish an Excellence Program on Mortality Surveillance for

Performance Monitoring

Institute continuous mortality-based monitoring to assess disaster impact and the

effectiveness of post-disaster interventions using the collaborations with UPR GSPH.

Determine a quality improvement program for death certication with training

for all physicians.

Establish a mechanism for continuous ow of surveillance results and

interpretation to decision makers

Improve efciency and timeliness of ow of information to decision makers and

engage stakeholders from civil society, the media and others.

Ensure provision of feedback to those involved in the death certication process

and in data analyses.

III. Recommendations for Future Advancement of Mortality

Surveillance and Natural Disaster Preparedness

Implement a cause-specic mortality analysis to establish causal pathways and identify

priority areas

Assess and strengthen public health functions.

Evaluate the burden of disease related to mortality following Hurricane María.

Advance the work on the analysis of small area statistics to identify heterogeneity within

municipalities related to mortality from Hurricane María.

Disseminate globally the experience gained by Puerto Rico in this major event.

vii

Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico

RECOMMENDATIONS ON CRISIS AND

MORTALITY COMMUNICATION IN

NATURAL DISASTERS

I. Strategic Objectives

To use credible, transparent and effective crisis and risk communication during natural disasters

as a mechanism for informing populations, protecting lives and instilling public trust. These

principles are recommended:

Preparedness, with planning as fundamental for effective crisis and emergency

risk communication

Credibility, as a critical factor for facilitating partnerships and protecting public health

Transparency, as a mechanism for strengthening and informing decision-making

Compassion, with acknowledgment and validation of individual and societal

emotions and concerns

II. Programmatic Recommendations for Natural Disaster

Crisis and Mortality Communications

Create an Integrated Puerto Rico Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication

Plan and Planning Process

Establish clear leadership by the Puerto Rico Emergency Management Bureau (EMB)

and the Central Communications Ofce for the development of a Puerto Rico Crisis and

Emergency Risk Communication Plan. Dene roles, levels of engagement, and specic

tasks for municipalities and all responsible agencies. Identify teams responsible for Plan

updates at municipal, agency, and central government levels.

Engage key stakeholders and local communities in the development of Crisis

and Emergency Risk Communication Plans at municipal, agency, and Puerto Rico

Government levels.

Coordinate and Build Capacity for Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication

Coordinate the Puerto Rico Plan with Agency and Municipal Crisis and Emergency

Risk Communication Plans.

viii

Establish an inter-agency committee to coordinate and oversee mortality surveillance

clearance and reporting to the public in disasters, to include communications and

technical experts.

Formalize a network of municipal communication liaisons to facilitate the timely

exchange of information with the central government pre- and post-disaster.

Ensure expertise in emergency communication planning and management, crisis and

risk communication, and mortality communication of government communication

personnel from agencies responsible for public health and safety functions in disasters.

Identify a cadre of ofcial spokespeople for disasters, including subject matter experts.

III. Recommendations to Build Crisis and Mortality

Communications Preparedness Capacity for

Natural Disasters

Update all Crisis and Emergency Communication Plans annually and following disasters.

Provide crisis and emergency risk communication training for communications

personnel, to include monitoring and addressing rumors and the effective use of social

media in disasters.

Implement media training for disasters with designated spokespeople.

Conduct annual emergency communication exercises, including stakeholders and local

communities.

Develop a dashboard that characterizes current crisis and mortality communication

capacity in disasters and tracks advancement over time for management and

accountability.

Conduct a KAP (knowledge, attitude and perception) population study to identify

communication strategies, messages, key audiences, vulnerable groups, and

communication channels in disasters.

Disseminate broadly promising practices and lessons learned for

community-based disaster.

ix

Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico

INTRODUCTION

The Governor of Puerto Rico invited the George Washington University’s Milken Institute

School of Public Health (GW SPH) to submit a proposal (PR Gov 2018) to determine the

excess mortality from Hurricane María.

The proposed study, titled “Ascertaining the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane

María in Puerto Rico,” contained three components: a mortality assessment, an

evaluation of the implementation of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s

(CDC) mortality reporting guidelines, and an assessment of crisis, emergency risk, and

mortality communications.

In its overall approach to the commissioned project, the GW SPH agreed to produce a

report with estimates of all-cause excess mortality associated with Hurricane María,

the team proposed to: a) use vital registration data from September 2017 to February

2018 to estimate standardized mortality ratios relative to prior years, adjusting for

age and sex composition of the population, as well as to produce a statistical model

that would account for these factors and produce estimates of excess mortality for

these months, including both point and condence interval estimates of the excess

all-cause mortality and a set of recommendations based on the ndings; (b) evaluate

the implementation of CDC guidelines for death registration during natural disasters

and evaluate the quality of death certicate records before and after the storm to

recommend improvements in these processes; and (c) review crisis and emergency

risk communication plans and procedures in place before and after Hurricane María,

interview participants and Government of Puerto Rico personnel to document how

communication processes were implemented, analyze key issues and events, assess

public perceptions of communications by the Puerto Rican Government, and provide

recommendations best on best practices in disaster communications.

In addition to providing an accurate estimate of excess mortality after the storm, the

GW SPH team also sought to inform the Government of Puerto Rico on the advantages

of using mortality data for monitoring the conditions after a natural disaster. The

study also assesses the government’s challenges in death certication, classication,

recording and reporting processes under normal circumstances and under the

stress of a hurricane disaster. In the future, these results may be followed with an

in-depth analysis of the cause-specic deaths directly and indirectly attributed to the

hurricane. The communication component sought to identify challenges within the

communications system as well as to recommend opportunities for addressing them.

The communications component may also be followed by an in-depth assessment of

communications capacity and processes, as well as the development of strategies to

enhance public health communications during crises.

1

Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico

RESEARCH TEAM

The GW SPH established a research collaboration with the University of Puerto Rico

Graduate School of Public Health (UPR GSPH) for project implementation. Other public

and private institutions and individual experts within and outside of Puerto Rico were

approached to collaborate on the project. Due to the level of con

dentiality required

for the project, as a rst step, a secure environment was established for data storage

and analysis. An interim report described much of the process to build the project,

including institutional arrangements, establishment of the secure warehouse, and the

collaborative environment (GW 2018).

Within the GW SPH, a multi-disciplinary team was assembled, consisting of

epidemiologists, a demographer, a public health nutritionist, environmental health

scientists, two public health research assistants, an anthropologist, a behavioral scientist

and two health communication experts. An external expert review panelist from Johns

Hopkins University joined the research team during the analysis of time-series of the

mortality data set. The UPR GSPH team included three tenured faculty, including a

biostatistician, an epidemiologist, and an epidemiologist with extensive experience

in community research and a biostatistics research assistant (Annex 1 identies the

research members). They contributed methodological expertise, community research

expertise and provided context for the GW SPH researchers on the Puerto Rico situation.

An expert review panel was established (Annex 2), with national and international

experts in different elds, to review the methods at different project stages. Similarly,

we had the support of a group of GW SPH global experts in medical humanitarian crisis

PURPOSE OF THE REPORT

The purpose of this report is to inform the citizens and the Government of Puerto

Rico about the project’s results. We believe the study ndings will enhance the

government’s capacity to develop reliable mortality surveillance systems for hurricane

disaster intervention and management and to implement efcient and robust public

communication systems in the context of a natural disaster. The report also describes

next steps in advancing a much-needed analysis on cause-specic mortality and in

performing an assessment of the capacity for implementing public health functions

that includes emergency surveillance and risk communication.

This report rst presents project methods and ndings and then proceeds to offer two

sets of recommendations.

For more details on the methodology, data and programs used in the excess mortality

calculations, these will be made available online at: http://

prstudy.publichealth.gwu.edu/

2

MORTALITY

METHODS

Assessment of Excess Mortality

Excess deaths are deaths that exceed the regular death rate predicted for a given population

(WHO 2018) had there not been a natural disaster or other unexpected or calamitous event,

such as an epidemic or industrial accident (Geronimus et al 2004; Haentjens et al. 2010).

Using vital registration data from seven years prior to the storm, we dened two

counterfactual scenarios for this analysis. The rst, which we have labeled the

‘census’ counterfactual, assumes the rate of change in the resident population

composition and distribution—both in terms of absolute size and factors associated

with differential exposure to the risk of mortality (including age, sex and municipal

socioeconomic development)

1

—remained unchanged after the hurricanes. The

second scenario estimates cumulative excess net migration from Puerto Rico in the

months from September 2017 through February 2018 and subtracts this from the

census population estimates in these months. This is labeled the ‘displacement’

counterfactual. Comparing these counterfactual estimates of mortality over the period

to that actually observed produces estimates of all-cause excess mortality. This excess

can be represented as a count of excess deaths, or a ratio of the number of observed

deaths to expected deaths had the hurricane not occurred.

Any estimation or comparison of mortality over time has to consider the population’s age

and sex distribution and seasonality. Similarly, it is important to take into account changes

in population size. In the case of Puerto Rico we reviewed in- and out migration over the last

decade and the net migration result was negative. The increase in out-migration has affected

the population’s demographics, and the storm accelerated this trend.

1. Age is categorized as between 0 and 39 years, 40 to 65 years, and 65 years and over. Sex is characterized as male and

female. Municipal level socioeconomic development is dened as the tertiles (or equal thirds of the distribution) of

the Municipal Socioeconomic Development Index (SEI), developed by the Puerto Rico Planning Board (Indice 2017).

This measure captures the underlying strength of municipal level structural and institutional capacities.

To estimate excess mortality associated with

Hurricane María, it was necessary to develop

counterfactual mortality estimates, or estimates

of what mortality would have been expected to

be had the disaster not occurred.

3

Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico

The GW Institutional Review Board (IRB) granted the project human subjects exemption

as it represented minimal risk. Data were transferred by the different government

agencies through a secure, private Secure File Transfer Protocol (SFTP) and stored and

managed in a protected environment certied against the HITRUST Common Security

Framework (CSF) for HIPAA compliance and meeting the FIPS 140-2 standard.

We began our analysis with descriptions of age-standardized mortality rates, age-

specic rates and rates by level of municipal socioeconomic development after the

storm relative to previous years. To estimate counterfactual mortality under the census

and displacement scenarios, we developed a series of generalized linear (GLM)

overdispersed log-linear regression models using the historical registration data from

July 2010 to August 2017. These models account for trends in population size and

distribution over this period in terms of age, sex and residence by municipal-level

socioeconomic development. We used the model results to project forward mortality

that would have been expected if the storm had not occurred and the population had

not changed (the census scenario), and explicitly accounting for the massive population

displacement away from the island occurring during this period (the displacement

scenario). Comparing these projections to observed mortality in the vital registration

data, we arrived at our estimates of excess all-cause mortality attributable to the storm.

In addition to the GLM models, we estimated a Generalized Additive Model (GAM) using

the same data as a robustness check on the GLM results. The GLM and GAM models

make different assumptions and treat the data differently, including in the specication

of overdispersion, autocorrelation and long-term and seasonal trends.

To provide context for our results, we have also replicated the analyses of others who

have attempted to estimate excess mortality in the post-María period, comparing their

estimates and their methodologies to those used here.

To perform this analysis, we obtained vital registration mortality data

including deaths by age, sex and municipality of residence from the Puerto

Rico Puerto Rico Vital Statistics Registry (PRVSR) for the period July 1, 2010

to February 28, 2018. We derived baseline estimates of population size in

each month from annual census estimates of population size by age, sex

and municipality of residence. Cumulative monthly population displacement

after the storm in each month was estimated using Bureau of Transportation

Statistics (BTS) data on monthly net domestic migration provided by the

Puerto Rico Institute of Statistics and a survey of airline travelers provided

by the Puerto Rico Planning Board (Planning Board 2018).

4

Death Certication Process

This study evaluated the implementation of the CDC procedures for mortality registration in

the aftermath of the hurricanes in Puerto Rico following the CDC evaluation protocol, Updated

Guidelines for Evaluating Public Health Surveillance Systems (German 2001).

Participants in the death certication process are the persons or organizations that

certify the occurrence of a death, generate, use or otherwise attest to deaths, mortality

registration and/or generate mortality data. For the death registration assessment,

potential interviewees included: physicians, PRVSR staff, funeral home directors,

hospital directors, forensic pathologists, Federal Emergency Management Agency

(FEMA) personnel and members of key associations. We chose interviewees from

different municipalities in Puerto Rico.

The interview guides were tailored to each participant group and informed consent

forms were developed. Spanish and English-language interview guides and informed

consent forms were approved by GW IRB and UPR GSPH. Each interview guide

described: 1) the regular processes, 2) organization or agency policies, and 3) changes

in processes during and after Hurricane María. Our team eld-tested the interview

guides in Puerto Rico; and also reviewed manuals for certication and registration of

deaths produced by the Puerto Rico Demographic Registry, Puerto Rico laws pertaining

to death registration, and several sets of guidelines from CDC and National Center for

Health Statistics (NCHS) on certication of deaths in disasters (Department of Health

(DoH) 2015a; DoH 2015b; CDC ND, CDC 2017).

Upon obtaining IRB authorization, our team traveled to Puerto Rico to conduct interviews —

26 in a two-week period. All interviewees received an informed consent form. To compare

Puerto Rico death certication procedures with those of the US mainland, we used the

same interview guide with a person from a local health department on the mainland that

historically had been affected by a major hurricane. The interviews were audio-recorded using

a secure device. Once transcribed, the recordings and transcriptions were placed in Armor,

the secure platform used by the project to store sensitive data.

The team generated information on (a) processes and procedures of

death certification, classification and registration in Puerto Rico, and

(b) participants involved in each process. Through this initial research,

the team identified all sources with the authority for completing the

death certification and registration process as well as the relevant

institutions and sectors (public and private) responsible for carrying

out each process. Researchers targeted individuals within specific

institutions for interviews and identied areas for conducting site visits.

5

Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico

Death Certication Data Quality

Studies have established that the quality of death certicate data are affected by the

individual completing the certicate, availability of decedents’ health records and the

vital statistics systems’ architecture where the data are entered, analyzed and reported.

Several studies have highlighted the inherent subjectivity stemming from individuals

who complete the death certicate; these studies document differences in death-

cause attribution of the same patients between physicians and within and between

medical specialties. For individuals who have no readily available or updated health

records, physicians often have to rely on the acute events leading to the death. In the

US, the NCHS reviews all death certicate data and applies algorithms to make the

nal determination of underlying cause of death and sequence of events that led to

the death. Typically, these are automated, with roughly 15% of death certicates being

manually coded.

One purpose of this analysis was to assess the quality of death certicate data after

Hurricane María compared to the two previous years.

We followed standard approaches to assess the quality of the mortality registration

process (Naghavi 2010, World Health Organization (WHO) 2013, Philips 2014). The

indicators we used were: percent of garbage codes as underlying cause of death,

percent of missing age or sex, percent of medically implausible diagnoses and average

number of causes of death reported per person per specied time period.

Data

We obtained vital registration mortality data including deaths by age, sex and

municipality of residence from the PRVSR for the years 2015 through 2017.

Mortality Registration Quality

Cause of death reporting/garbage codes: Mis-assignment of the underlying cause of

death was calculated using a combination of the methods described by Naghavi (2010)

and Philips et al. (2014) and by WHO (2013) and comparing both. Garbage codes refer

to diagnoses that should not be considered as an underlying cause of death or assigning

deaths to causes that are not useful (Naghavi 2010). Garbage codes were classied into:

Type 1, codes without any inherent information about the underlying cause of death

(e.g., heart beat abnormalities, dizziness); Type 2, codes that describe intermediate

causes of death (e.g., heart failure, septicemia, or pulmonary embolism); Type 3, codes

that represent immediate causes of death that are the nal steps in a disease pathway

leading to death (e.g., cardiac arrest, respiratory failure); and Type 4, unspecied causes

The team analyzed death certicate data quality to

formulate recommendations that would improve death

certication procedures during and after a disaster.

6

within a larger cause (e.g., unspecied bacterial infection, metabolic disorder).

Several experts meet on a regular basis to revise the denitions of these groupings.

We used the expanded 1 to 4 garbage coding denitions from Philips et al. (2014)

and personal communication. We also calculated garbage codes as dened by WHO.

Completeness of age and sex: To assess quality of age and sex reporting, we calculated

the number of deaths with unspecied date of birth, age, sex or a combination of these

as a fraction of all deaths reported.

Internal consistency: Following the procedures used by Philips et al. (2014) and by

WHO (2013), we calculated the number of implausible cause of death assignments

for any given age or sex. For example, females diagnosed with testicular or other male

reproductive-organ cancers, males with obstetrical conditions, pregnancy-related

mortality for males or for females under age 10.

Timeliness: This indicator refers to timeliness on many levels. For this analysis,

researchers calculated the number of days between date of death and date of

registration and assessed whether delays were related to the hurricane.

Number of causes of death reported: We calculated the number of causes of death

assigned for each decedent and then calculated the average in each of the specified

time periods to assess whether this was impacted by the event.

We assessed statistical significance using t-tests, chi-square tests, and simple linear

regression models, as appropriate (Suárez, 2017).

7

Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico

Figure 1. Age-Standardized Monthly Mortality by Year (per 10,000 inhabitants),

Puerto Rico, 2010-2011 to 2017-2018. U.S. Census and Displacement Scenarios

for 2017-2018

FINDINGS

Ascertainment of Excess Mortality

The PRVSR documented 16,608 deaths from September 2017 to February 2018—9,054

males and 7,554 females. Approximately 77% were older adults (65+ years), and 18%

resided in the municipalities with low socioeconomic development. We estimated that

in mid-September 2017 there were 3,327,917 inhabitants and in mid-February 2018

this number was 3,048,173 inhabitants of Puerto Rico, a total population reduction of

approximately 8%. This was factored into the migration “displacement scenario” and

compared with the “census scenario.”

Age-adjusted mortality rates for Puerto Rico tend to be higher in the winter and

early spring, declining in the summer months (Figure 1). Mortality has been slowly

declining from 2010 on, but increased markedly in the period after September 2017,

most dramatically under the displacement scenario accounting for migration after the

hurricane.

8

Results from the preferred statistical model, shown below, estimate that excess mortality

due to Hurricane María using the displacement scenario is estimated at 1,271 excess

deaths in September and October (95% CI: 1,154-1,383), 2,098 excess deaths from

September to December (95% CI: 1,872-2,315), and, 2,975 (95% CI: 2,658-3,290)

excess deaths for the total study period of September 2017 through February 2018.

Table 1 shows observed, predicted and excess mortality by month for the study period

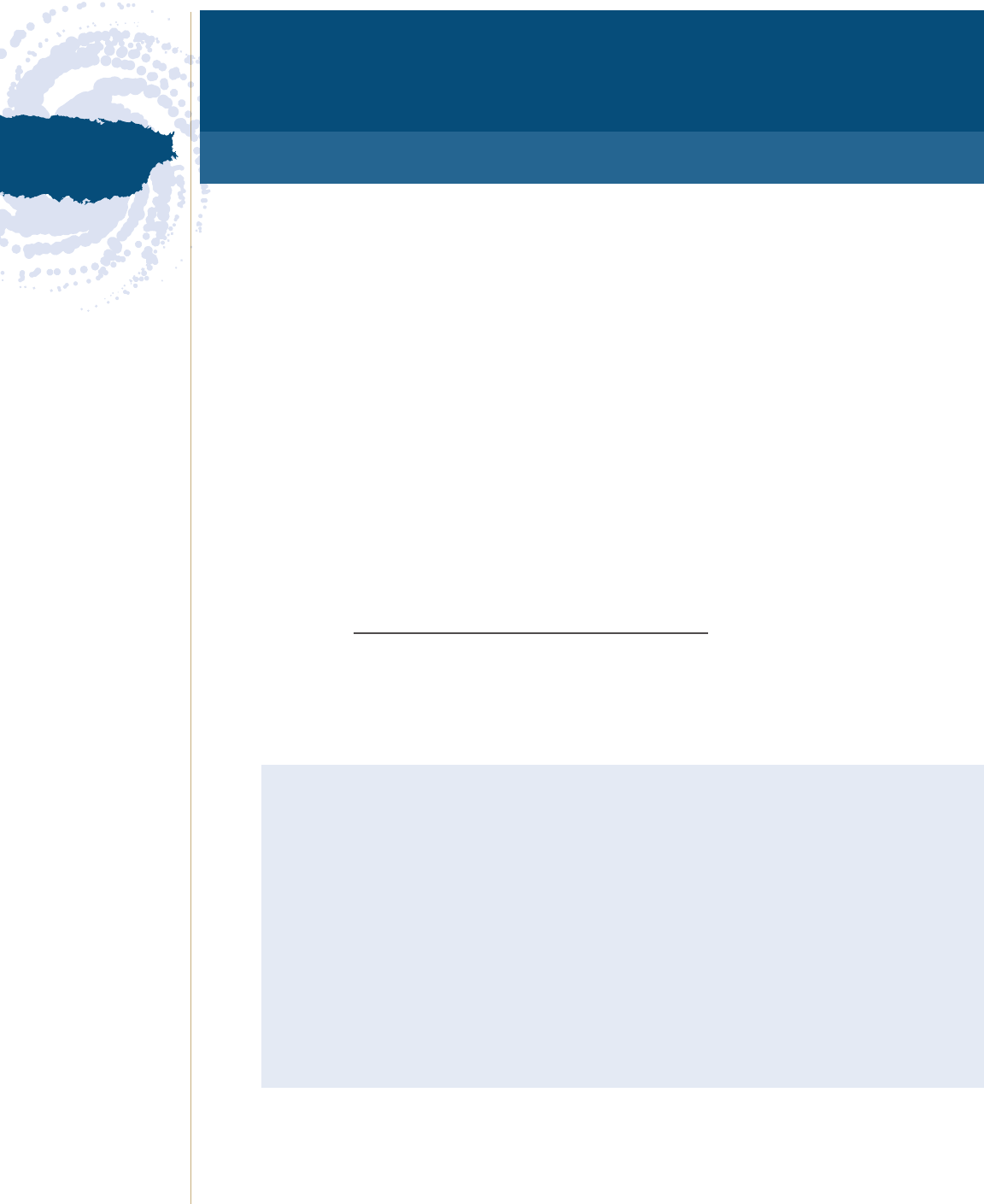

as well as the total study period.

Table 1. Observed, Predicted and Excess (95% CI) Mortality, Puerto Rico,

September 2017 to February 2018, Model 3, Displacement Scenario

SEPT-OCT 2017 SEPT-DEC 2017 SEPT 2017-FEB 2018

OBSERVED

5,921 11,375 16,608

PREDICTED

4,650 9,277 13,633

EXCESS

1,271 2,098 2,975

95% CI

(1154, 1383) (1872, 2315) (2658, 3290)

OBSERVED/PREDICTED

1.27 1.23 1.22

Every social stratum and age group was affected by excess mortality,

however, the impact differed by age and socioeconomic status

(Figures 2 & 3). Risk of death was higher and persistent until the end

of the study period for populations living in low socioeconomic

development municipalities (a ratio of 1.5 at the end of February 2018).

Older males (65+) experienced continuous elevated risk of death through

February, while most other groups approach the baseline mortality risk at

2 and 4 months post-hurricane, and all do so by February.

9

Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico

Figure 2. Estimated Relative Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in

Puerto Rico, Per Month, by SEI Category

Figure 3. Estimated Relative Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in

Puerto Rico, Per Month, by Sex and Age Group

10

No areas of the island were unaffected, but in its aftermath, some municipalities suffered

greater increases in mortality. Figure 4 displays the estimated percentage increase in the

crude mortality rates by municipality (not accounting for age distribution differences)

for the period inclusive of September-February 2017-18 relative to the average rate in

the same period in 2015-16 and 2016-17 under displacement scenario. Signicant

differences between these two periods are denoted with asterisks. As can be

seen from this gure, the largest mortality differentials are concentrated in the northeast,

and to a lesser extent, southwest portions of the island. Overall, however, approximately

40% of municipalities saw signicant increases in mortality during the study period than

in the comparable period of the previous two years.

Figure 4. Estimated percentage increase in crude mortality rates by

municipality in Puerto Rico from September 2017-February 2018.

The ofcial government estimate of 64 deaths from the hurricane is low primarily

because the conventions used for causal attribution only allowed for classication

of deaths attributable directly to the storm, e.g., those caused by structural collapse,

flying debris, floods and drownings (see below). During our broader study, we

found that many physicians were not oriented in the appropriate certification

protocol. This translated into an inadequate indicator for monitoring mortality in the

hurricane’s aftermath. Verification of attribution takes time, while excess mortality

estimation is a more immediate indicator.

11

Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico

Death Certication Process

Based on a review of scientic literature, laws and manuals, as well as interviews on

the death certication and registration processes in Puerto Rico, we established that

the persons authorized to complete death certicates include physicians and forensic

physicians. Most physicians have no formal training in completing a death certicate

and thus are not aware of appropriate death certication practices, especially in a

disaster setting. When the special CDC guideline was disseminated after the disaster,

some of those who had access to it found that it conicted with what they had previously

learned. Those interviewed said they did not receive information about how to certify

deaths during, or in conditions created by, a disaster. Several interviewed physicians

were asked about the CDC guidelines the PRVSR circulated after the hurricane that

recommended they ll out a section in the death certicate with information or other

conditions that contributed to the death. Several said— as did a spokesman for the

physician community in hearings—that they understood this section as seeking more

information about health conditions. A few interview respondents indicated some

reasons for reluctance to relate deaths to hurricanes, including concern about the

subjectivity of this determination and about liability.

The analysis shows that physician unawareness of appropriate death

certification practices after a natural disaster and the Government of

Puerto Rico’s lack of communication about death certificate reporting

prior to the 2017 hurricane season substantially limited the count of

deaths related to María.

There was also a communication problem between the PRVSR

and other government agencies and participants in the death

certification and registration process, physicians, funeral home

directors, hospitals and the organizations that represent them

(e.g., the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Puerto Rico and

the Association of Hospitals of Puerto Rico). Many stated that the

Puerto Rico Department of Health (DoH) and the Puerto Rico

Department of Public Safety (DPS) did not notify them about the

CDC special guidelines for correct documentation of cases, on the

importance of correctly documenting deaths related to the

hurricane or on an emergency protocol for handling these cases.

12

The lack of training on death certicate completion is also a problem

on the mainland, and several jurisdictions have sought to remedy this

deciency by creating and requiring training courses on death certication

for physicians and other personnel responsible for completing death

certicates. NCHS has developed an e-course as well. To date, there are

no formal courses on death certication in natural disasters for persons

who ll out death certicates.

Death certication and registration processes in Puerto Rico were affected by Hurricane

María. The PRVSR ofces sustained damages and did not have electric power to operate

immediately after the hurricane. Even for the ofces which had generators, the electronic

system used was not always operational. PRVSR leadership re-deployed staff to ofces

that were still operational and to San Juan so that, at the very minimum, staff could

receive information and begin processing the deaths. Because the agency’s electronic

system was ofine, everything was done on paper, and all certicates were collected

by supervisors and taken to San Juan for quality review and data entry. This resulted in

delays in death registration, ranging anywhere from 7-10 days to 17-27 days. Based

on a concurrent study of quality of the death certicate data, it does not appear to have

affected the completeness of the certicates (see death certication quality).

Once operations resumed, the PRVSR personnel tracked the data coming in. When they

saw that the numbers of death per day were considerably higher than normal, which is

about 75 deaths per day, they began checking death certicates and found that those

relating the deaths to the hurricane were scarce. The PRVSR sought to disseminate the CDC

guidelines to participants in the certication process (physicians, hospitals, funeral home

directors, etc.)

PRVSR personnel indicated they provided the information to the different groups via email,

through the weekly meetings at the government Center for Operations in Emergencies

(COE), as well as through interviews with the press.

According to PRVSR personnel, a very small number of those completing death certicates

did relate the deaths to the hurricane. Most other certicates lacked such information. This

reduced the number of death certicates that indicated a relationship with the hurricane.

As part of this study, the team also interviewed individuals involved in death certication in

mainland states and at the NCHS. According to these respondents, the quality of mortality data is

affected by how much the person lling out the death certicates knows about this task

13

Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico

Several laws govern the certication of death in Puerto Rico, including the laws that set

up the PRVSR, the Puerto Rico Bureau of Forensic Sciences (BFS), as well as the law for

Funeral Homes (Ley del Registro General Demográco de Puerto Rico, 1931; Ley para

declarar la muerte en caso de eventos catastrócos, 1985; Ley del Departamento de

Seguridad Pública de Puerto Rico, 2017;). In addition, the PRVSR has created

instruction manuals, available online, for lling out death certicates (DoH 2015

a

;

DoH 2015

b

). Nevertheless, none of these laws or manuals address death certication

during disasters. A low impact of federal guidance to support mortality-surveillance

disaster planning both at the BFS and PRVSS was identied.

Death Certication Quality

We compared PRVSS data from September 2017 to December 2017 with the same

period in 2015 and 2016. In addition, we compared the period from September 20 to

September 30 in each of the 3 years.

Table 2. Percent of Garbage Codes as the Underlying Cause of Death by Type and Year

from 2015-2017

YEAR

TYPE 1

GARBAGE CODES (%)

TYPE 2

GARBAGE CODES (%)

TYPE 3

GARBAGE CODES

TYPE 4

GARBAGE CODES

2015

20.1 4.1 3.9 6.5

2016

20.1 3.1 4.3 5.8

2017

23.6 6.3 3.8 6.3

Mortality Registration Quality

Cause of death reporting/Garbage codes: Table 2 shows the trends in Types 1-4 garbage

codes from 2015-2017. Overall, about 20% of the PRVSS records had garbage codes of

at least one type as the underlying cause of death over the study period. However, there

was a statistically signicant increase in Type 1 and Type 2 garbage codes in the period

following Hurricane María compared to the same period in the prior year. There was no

difference in the percentage of Type 3 and Type 4 garbage codes following Hurricane María

Completeness of age and sex: Completeness of death certicate quality was high with

respect to age and sex, which are two indicators widely used to assess mortality registration

quality. Less than 0.1% of records had missing age or sex. There was no statistically signicant

association between the event and completeness of age or sex data.

Internal consistency: With respect to internal consistency, less than 1% of death

certicates had medically inconsistent diagnoses in the underlying cause of death as

dened by Philips et al. (2014), and there was no statistically signicant association

between the event and internal consistency.

14

YEAR

TYPE 1

GARBAGE CODES (%)

TYPE 2

GARBAGE CODES (%)

TYPE 3

GARBAGE CODES

TYPE 4

GARBAGE CODES

2015

20.1 4.1 3.9 6.5

2016

20.1 3.1 4.3 5.8

2017

23.6 6.3 3.8 6.3

Figure 5. Length of Time (In Days) between Date of Death and Date of

Registration of Death (Timeliness) before (September-December 2016)

and after Hurricane María (September-December 2017)

Number of causes of death reported: There was a statistically signicant decrease in

the number of causes of death listed on a death certicate after the hurricane, with

about 47% of death certicates listing two or more causes of death in 2016 compared

to 44% in 2017.

The results presented herein highlight overall improvements that were made to

Puerto Rico’s death registration system over the four years prior to Hurricane María, as

evidenced by low rates of garbage codes, completeness in age and sex recording, high

rates of internal consistency and improvements in timeliness. Following Hurricane

María, there was a slight, although statistically signicant, increase in the percentage of

Type 1 and Type 2 garbage codes. This is in line with our ndings from the assessment

of the death certication process in the previous section that described biased coding

of death certicates in response to inadequate health infrastructure. As stated in the

previous section, the time from date of death to registration also increased signicantly

following the hurricane. This also corroborates the results of our qualitative assessment.

Timeliness: There was a statistically signicant delay in the number

of days between date of death and date of death registration, with an

average of 17 days in the period after the hurricane compared to 12

days in the prior year. Figure 5 shows the percentage of certicates per

day processed for the pre-María period of September-December 2016,

compared to the same period in 2017.

15

Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico

RECOMMENDATIONS

OVERALL POLICY GOAL FOR MORTALITY

SURVEILLANCE AND COMMUNICATIONS

To assure the capacity of mortality surveillance and the communication of its results to support

policies and interventions for the protection of people´s life and health during crises produced by

natural disasters in Puerto Rico

RECOMMENDATIONS ON MORTALITY

SURVEILLANCE FOR NATURAL DISASTERS

I. Strategic Objectives

To have a reliable and resilient institutional mortality surveillance process that provides

trustworthy and accurate evidence during natural disasters to:

Establish the magnitude of the disaster’s impact

Identify areas and groups of highest risk

Monitor the performance of public health protection and prevention

Inform policy-making and program implementation

We recommend the following guiding principles:

Readiness: establish a routine process

Rigor: based on valid methods

Timeliness: delivering on time

Common good: having as a priority the welfare of all

16

II. Programmatic Recommendations for Natural

Disaster Mortality Ascertainment

A. Development of an Organizational Agenda

Develop a federal and Puerto Rico policy architecture

Establish a planning process for hurricane disasters with overall

responsibility under the Ofce of the Governor.

Update the Public Health and Medical Situation Awareness Strategy

2014 to consider surveillance needs for states and territories and

provide effective guidance for the specicities of natural disasters

(DHHS, 2015).

Create a culture of preparedness and planning at the federal

and Puerto Rico levels, including collaborative data-sharing and

monitoring during the emergencies.

Dene clear leadership

Under all circumstances, the Puerto Rico DoH has responsibility

for all population mortality surveillance. The DoH has the power of

legal attribution, it is the counterpart to the federal governmental

and international agencies that address these issues, and it has to

be able to use the surveillance mechanism for effective and timely

intervention.

Within the DoH, the PRVSR has to be the ofcial site for integration of

such information; this ofce collects statistical data and is responsible

for analysis. The information produced by the PRVSR should be

integrated with the DoH surveillance system. This integration should

be established by administrative order.

The DoH needs to be consulted in policy-making discussions and set

norms and guidance on mortality certication during emergencies.

17

Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico

Assure strong professional capacity

Train public health professionals in public health preparedness. We recommend that the

Schools of Public Health of Puerto Rico and the continental US establish programs in

this eld to advance Healthy People 2020 goals (CDC 2013).

Assess public health capacity to effectively implement public health functions within

Puerto Rico, including mortality surveillance.

Train personnel to manage mortality surveillance at the local and central levels

of the PRVSR.

Fully staff the PVRSS for key positions with graduate degrees in demography and other

public health disciplines (e.g., biostatistics, epidemiology, data management).

Complete the stafng at the BFS. Surge planning should call for additional personnel

beyond a fully staffed organization.

Review the legal framework

Dene the Puerto Rican DoH’s accountability and review the legal basis supporting

the attribution of responsibilities between the DoH and DPS on the topic of mortality

surveillance and reporting.

Protect medical personnel from consequences of certifying the circumstances of a death

in a natural disaster. A legal framework should also protect medical facilities in fullling

their mandates for certication.

Establish a legal agreement for the continuous information transference and updating

to the DoH for mortality surveillance with the BFS, the Census Bureau and the Puerto

Rico Institute of Statistics.

Assign needed nancial resources and secure reliable infrastructure

Assure the integrity, completeness and resilience of strategic sites, the PRVSS and

the BFS, with, for example, reliable electrical power, safety installations, redundancy

systems, backups, transportation and alternative telecommunication capabilities. Put in

place Continuity of Operations (COOP) plans.

The federal government should support the implementation of this agenda and its

nancing. An executive order should be issued for an expansion of the regular operating

budget to all organizations and especially the DoH, BFS, PRVSR.

18

B. Establish an Excellence Program on Mortality

Surveillance for Performance Monitoring

Use mortality-based monitoring to assess disaster impact and the

effectiveness of interventions in the aftermath

Establish a continuous surveillance system based on the principle of

transparency, staffed by PRVSR and DoH professionals. The system can be

used as a public health tool for systematic analysis and interpretation of

total all-cause deaths.

Develop specic indicators and special monitoring of vulnerable groups

(low SEI and older adults).

Establish collaborations of the UPR GSPH with the government

and, particularly, the DoH for stafng and for students’ professional

development, laying foundations for a Center of Excellence.

Differentiate between terms. Use the term hurricane (or other natural

disaster event) excess death as the indicator to track and identify departures

from predicted/expected mortality. It should use hurricane-attributable

mortality for conrmed cases to both monitor and certify death.

Establish a system of continuous modeling of mortality trends using the

models provided, with constant updates of sociodemographic information.

Allow for recovery monitoring in the system and dene the scope

and duration of remediation interventions by federal and territorial

governmental and social agencies.

Establish a continuous quality improvement program for

death certication

Continuously measure indicators and establish a monitoring system,

particularly when changing to the e-certication system. Include a

continuous measurement of indicators on death certication quality in

the monitoring system. Make this information available to the medical

community at all times.

Train all medical doctors on death certication. Use existing, publicly

available online courses by Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) or

NCHS. Ensure this training is a requirement of College of Physicians and

Surgeons for medical accreditation.

Implement collaborations of the DoH and the BFS with universities such

as UPR GSPH to train personnel on quality improvement and in-depth

studies of death certication.

19

Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico

C. Establish a Mechanism for Continuous Flow of Analysis

and Interpretation of Results to Decision Makers

Improve efciency of ow of information to decision makers

Design instruments to convey results in a timely manner to key decision makers during

a natural disaster. Engage stakeholders from civil society, the media and other groups.

Base decisions on evidence from the continuous monitoring system and its indicators.

Ensure provision of feedback to those involved in the death certification process

Convey results in a timely manner to those generating them, such as medical doctors.

Develop instruments to effectively and efciently communicate with these target groups

as part of establishing a surveillance system with a bidirectional ow of information.

III. Recommendations for the future advancement and in

preparation for other potential natural disasters

Analyze cause-specic mortality to establish causal pathways and identify priority areas

(see Annex 3).

Assess and strengthen public health functions at the DoH.

Evaluate the burden of disease related to mortality from Hurricane María.

Advance the work on the analysis of small-area statistics to identify the heterogeneity

within municipalities in the mortality experience from Hurricane María.

Disseminate globally the experience gained by Puerto Rico in this major event.

20

Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico

COMMUNICATIONS

METHODS

Assessment of Crisis and Mortality Communications

and the Information Environment

The current study includes an assessment of disaster and/or communications planning

and actions taken by the Puerto Rican Government before and after Hurricane María, with

an emphasis on the plans in place at the time of the hurricane, the number of trained staff

dedicated to crisis and emergency risk communication, spokespersons’ interaction with the

media and stakeholder perceptions of the government’s risk communication and reporting

of mortality. The communication assessment methodology, instruments and analytical

framework were informed by established guidelines and principles, which are supported

by robust scientic evidence detailed in: 1) CDC’s Crisis Emergency Risk Communication

(CERC) manual (CDC 2014), 2) WHO’s Communicating Risk in Public Health Emergencies

guidelines (WHO 2017), 3) WHO’s Effective Media Communication During Public Health

Emergencies handbook (WHO 2005) and 4) FEMA’s A Whole Community Approach to

Emergency Management (FEMA, 2011).

Government Personnel and Key Leader Interviews: Two bilingual GW SPH researchers

conducted 33 interviews from April-June, 2018. Eleven interviews were conducted

with Puerto Rico Government agency leaders and communication personnel, and

22 with key leaders representing different stakeholder groups, described more below.

Puerto Rico Government personnel interview participants were identied

based on their role in overseeing government communications personnel,

or in coordinating, developing, approving and/or disseminating public

health, public safety or mortality information to the public. We interviewed

government agency personnel to gain their perspective on planning and

actions related to crisis and public health communications during the pre-

and post-hurricane periods.

22

Government personnel recruited for interviews included agency leaders; press/

communications directors; a demographer with involvement in vital statistics data

management; a health-related program director; and a risk communication analyst.

Interview guides inquired about the following topics: the agency’s role in public

health communication and/or mortality reporting, including communication during an

emergency; communication plans or other processes for the preparation, approval and

dissemination of information to the public; target audiences for communication; inter-

agency collaboration; communications experiences related to Hurricane María; and

recommendations for future communications.

We selected key leader interview participants to represent diverse segments

of society or broadly dened stakeholder groups. These interviews were

meant to understand the range of experiences from Hurricane María,

involvement in disaster planning and communications among leaders in

various communities around the island as well as their perceptions of the

government’s risk communication and mortality reporting.

These interviews were conducted within a sample of Puerto Rico municipalities,

which were selected to obtain a sample with diversity according to the following

criteria: geographical distribution; regional representation; socioeconomic status;

predominant political afliation; demographics; and proximity to hospitals/clinics.

Interview participants included: municipal mayors, community leaders, emergency

management staff, police, a faith leader, health care providers, non-prot organization

staff, and a funeral director. The key leader interview guide focused on the following

areas: experiences related to Hurricane María; perceptions of mortality reporting

and reassessment; risk-communication information received; recommendations for

future communications; and identication of target audiences, optimal channels and

community outreach strategies for information dissemination.

All interviews were audio-recorded using a secure device. The Spanish-language

transcripts were analyzed using qualitative data analysis methodology, which entails

reviewing transcript text, identifying where specic topics are discussed, tagging that

text with codes that represent particular themes, summarizing responses by theme

and then conducting thematic analysis. From this systematic process, researchers

identied areas of consensus and discord among participants, which facilitated the

characterization of experiences and perceptions. The interviews were analyzed in

accordance with guidelines outlined in the documents identied above.

23

Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico

Press Releases and Press Conferences: Three GW SPH researchers with expertise in public

health communications, risk communication and media systematically reviewed ofcial

press releases the Governor’s Ofce disseminated and press conferences from September

20, 2017-February 28, 2018. These information sources were examined to identify key

messages for hurricane-related mortality reporting to evaluate information content, the

manner in which information was delivered and spokespeople performance.

We reviewed 17 press releases provided by the Governor of Puerto Rico’s Central

Communication Ofce and 20 press conferences, 10 of which were transmitted via the

governor’s Facebook account and 10 of which were provided in audio recording format.

Digital Media Coverage & Social Media Commentary: Three GW SPH researchers with

expertise in public health communications, risk communication and media compiled

and reviewed media coverage from major English- and Spanish-language news outlets

pertaining to hurricane-related mortality reporting, as well as related social media

commentary from September 20, 2017-February 28, 2018 in order to identify factors

that may have contributed to public concerns about mortality reporting. We reviewed

172 digital media news stories and related social media posts. We analyzed these

information sources to identify the following: reasons and timing of the dissemination

of mortality data, contradictory mortality data from Puerto Rico Government spokespeople

and alternative sources, information used to consider a death as hurricane-related,

information gaps lled by non-ofcial information and perception of the accuracy and

transparency of the Puerto Rico Government’s messages about death gures.

GW SPH sought to determine the extent to which trust, credibility,

transparency and accountability were communicated, according to