RESEARCH REPORT

WHEN PARENTS SEPARATE:

FURTHER FINDINGS FROM THE

NATIONAL LONGITUDINAL SURVEY

OF CHILDREN AND YOUTH

2004-FCY-6E

When Parents Separate: Further Findings from the National

Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth

Phase 2 of a three part project commissioned by the

Family, Children and Youth Section of the Department of Justice Canada on:

The Impact of Parents’ Family Transitions on Children’s Family Environment and

Economic Well-Being: A Longitudinal Assessment

Prepared by:

Heather Juby, Nicole Marcil-Gratton and Céline Le Bourdais

Centre interuniversitaire d’études démographiques

Institut national de la recherche scientifique / Université de Montréal

Presented to:

Family, Children and Youth Section

Department of Justice Canada

The results presented are based on analyses conducted in the Quebec Inter-University Centre for

Social Statistics that provides researchers with access to the detailed longitudinal survey data

collected by Statistics Canada. The opinions expressed here do not represent the views of

Statistics Canada.

The views expressed in this report are those of the authors

and do not necessarily represent the views of

the Department of Justice Canada.

Aussi disponible en français

This report may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, without charge or further

permission from the Department of Justice Canada, provided that due diligence is exercised in

ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; that the Department of Justice Canada is

identified as the source department; and that the reproduction is not represented as an official

version of the original report.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada,

represented by the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada, 2005

- i -

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ v

INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1

I THE CHANGING FAMILY ENVIRONMENT AT BIRTH ............................................ 5

Married, cohabiting or alone?............................................................................................. 6

First or second family?...................................................................................................... 10

The context at birth and family transitions....................................................................... 13

II SPLITTING UP ................................................................................................................ 17

Recent trends in separation............................................................................................... 17

Life with a lone parent...................................................................................................... 19

Differences by province.................................................................................................... 19

III SHARING CUSTODY..................................................................................................... 23

Are more children living in shared custody when parents separate?................................ 26

What type of sharing patterns are most commonly selected

by parents who share custody? ......................................................................................... 29

Does the choice of arrangement depend on the child’s age when parents separate?........ 30

How do shared living arrangements evolve through time? .............................................. 30

From shared to sole custody—a multivariate analysis ..................................................... 31

IV PHYSICAL CUSTODY ARRANGEMENTS AND CHILD SUPPORT:

NEW INFORMATION .................................................................................................... 35

New information on custody arrangements...................................................................... 35

New information on child support.................................................................................... 41

DISCUSSION ............................................................................................................................... 49

REFERENCES ............................................................................................................................. 53

- ii -

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1.1 Proportion of children aged 2-13 years in 1996-97 who have experienced

at least one family transition, by age group, and according to

a) the parents’ conjugal status and b) the family context at the child’s birth,

NLSCY, longitudinal cohort ..................................................................................... 14

Table 3.1 Distribution of children with separated parents in 1994-95 and 1998-99,

according to type of custody and living arrangements at separation,

NLSCY, Cycles 1-3................................................................................................... 26

Table 3.2 Impact of given variables on the probability that children (aged 0-15 years in

1998-99) live in shared custody or with their father rather than remaining

with their mother when parents separate, NLSCY, Cycle 3 ..................................... 28

Table 3.3 Impact of given variables on the probability that children

(aged 0-15 years in 1998-99) in shared custody at separation

are living with their mother or father in 1998-99 rather than

remaining in shared custody, NLSCY, Cycle 3 ........................................................ 32

Table 4.1 Impact of given variables on the probability that children, aged 4-15 years

in 1998-99, whose parents separated in the two previous years, saw the

“other parent” more or less frequently than agreed, NLSCY,

Cycle 3....................................................................................................................... 38

Table 4.2 Impact of given variables on the probability that children in sole custody are

consulted about living arrangements by separating parents, among children aged

4-15 years in 1998-99, whose parents separated in the previous two years,

NLSCY, Cycle 3........................................................................................................ 41

Table 4.3 Proportion of child support agreements that include child support payments,

among children aged 4-15 years in 1998-99, whose parents separated in

the two previous years, according to various characteristics, NLSCY, Cycle 3....... 45

Table 4.4 Impact of given variables on the probability that a child support agreement

does not include child support payments, among children aged 4-15 years

in 1998-99, whose parents separated in the previous two years,

NLSCY, Cycle 3........................................................................................................ 46

Table 4.5 Distribution of children aged 4-15 years in 1998-99, whose parents separated

in the previous two years, according to the method and regularity of child support

payments, and the proportion of payment received, NLSCY, Cycle 3..................... 47

- iii -

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1.1 Type of parents’ union at child’s birth, for children aged 2-13 years

in 1996-97, NLSCY, longitudinal cohort .................................................................. 6

Figure 1.2 Distribution of children according to parents’ conjugal status at

the child’s birth for various cohorts of children, NLSCY,

Cycles 1 and 3, Inter-regional variations through time.............................................. 7

Figure 1.3a Distribution of children according to parents’ conjugal status at

the child’s birth, by region of Canada, 1983-84 cohorts, NLSCY, Cycle 1.............. 8

Figure 1.3b Distribution of children according to parents’ conjugal status at the child’s

birth, by region of Canada, 1997-98 cohorts, NLSCY, Cycle 3................................ 8

Figure 1.4 Family context at birth, for children aged 2-13 years in 1996-97, NLSCY,

longitudinal cohort................................................................................................... 11

Figure 1.5 Distribution of children born in two-parent families according to

the family context at birth, 1983-84 and 1997-98 cohorts NLSCY,

Cycles 1 and 3.......................................................................................................... 12

Figure 1.6 Distribution of children, aged 2-13 years in 1996-97, born in two-parent

families by family context and by type of parents’ union, NLSCY, Cycle 2,

longitudinal cohort................................................................................................... 13

Figure 2.1a Cumulative proportions of Canadian children who experienced their parents’

separation, various birth cohorts, NLSCY, Cycle 3................................................. 18

Figure 2.1b Cumulative proportions of Canadian children born to a lone parent

or experiencing their parents’ separation, various birth cohorts,

NLSCY, Cycle 3...................................................................................................... 18

Figure 2.2a Cumulative proportions of children who have experienced their parents’

separation by age 10 years, by region of Canada, 1983-85 and 1989-91 birth

cohorts, NLSCY, Cycle 3 ........................................................................................ 20

Figure 2.2b Cumulative proportions of children who have experienced a lone-parent

episode by age 10 years, by region of Canada, 1983-85 and 1989-91

birth cohorts, NLSCY, Cycle 3................................................................................ 21

Figure 3.1 Distribution of minor children for whom there was a custody order at divorce,

according to the type of arrangement, Canada, 1970-2000 ..................................... 24

Figure 3.2 Distribution of children whose parents separated in the two years

preceding Cycles 1 (1994-95) and 3 (1998-99), according to the living

arrangements at separation, NLSCY........................................................................ 27

Figure 3.3 Distribution of children, aged 0-15 years in 1998-99, in shared custody at

separation, according to the type of shared living arrangements,

NLSCY, Cycle 1-3................................................................................................... 29

- iv -

Figure 3.4 Living arrangements by 1998-99 for children (aged 0-15 years)

who were in shared custody at separation, NLSCY, Cycle 3.................................. 31

Figure 4.1 Living arrangements and contact with other parent in 1998-99 for children,

aged 4-15 years at Cycle 3, whose parents separated in the previous

two years, NLSCY, Cycle 3..................................................................................... 36

Figure 4.2 Distribution of children aged 4-15 years in 1998-99, whose parents

separated in the previous two years, according to the frequency with which

the child saw the “other parent” relative to the frequency agreed,

NLSCY, Cycle 3...................................................................................................... 37

Figure 4.3 Distribution of children aged 4-15 years in 1998-99, whose parents

separated in the previous two years, according to the reason given for

less frequent contact than agreed with the other parent, NLSCY, Cycle 3 ............. 39

Figure 4.4 Distribution of children aged 4-15 years in 1998-99, whose parents

separated in the previous two years, according to the child’s involvement in

decisions regarding custody and contact arrangements, by age at separation,

NLSCY, Cycle 3...................................................................................................... 40

Figure 4.5 Distribution of children aged 4-15 years in 1998-99, whose parents separated

in the previous two years, according to the existence and type of child support

agreement, NLSCY, Cycle 3 ................................................................................... 42

Figure 4.6 Distribution of children aged 4-15 years in 1998-99, whose parents separated

in the previous two years, according to the reason why no agreement

was made on child support payments, NLSCY, Cycle 3......................................... 43

Figure 4.7 Distribution of children aged 4-15 years in 1998-99, whose parents separated

in the previous two years, according to the regularity of support payments

and the type of support agreement, NLSCY, Cycle 3.............................................. 48

Figure 4.8 Distribution of children aged 4-15 years in 1998-99, whose parents separated

in the previous two years, according to the proportion of child support

payments made and the type of support agreement, NLSCY, Cycle 3.................... 48

- v -

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Background

This report was commissioned by the Child Support Team of the Department of Justice Canada

as part of a project using data from the “Family History and Custody” section of the National

Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY) to explore the impact of parents’ family

transitions on children’s family environment and economic well-being. This is the first of two

reports exploring the way in which parents’ conjugal behaviour shapes the family life course of

their children. In this report, we focus on the beginning of the child’s life course, situating the

birth within the family life course of the parents, and looking at the first and most common

transition experienced by children: their parents’ separation.

The report is divided into four sections. The first two set the scene, updating and expanding

earlier analyses of changes in the context at birth for children born during the last two decades of

the 20

th

century, comparing the different regions of Canada, and exploring how this evolution

influences the likelihood that parents separate. The other two sections focus on the way separated

parents share responsibility for their children’s physical and economic support, with particular

reference to shared “physical” custody,

1

and to the new information on custody and child support

collected for the first time at Cycle 3.

Research Approach

With information about the same children collected at intervals of every two years, the NLSCY

is a unique data source for studying Canadian children and families at the turn of the 21

st

century.

The present research is based on data from the first three survey cycles, conducted during the

winters of 1994-95, 1996-97 and 1998-99. By Cycle 3, the original longitudinal cohort numbered

approximately 15,000 children aged 4-15 years; additional samples of young children were

added at Cycles 2 and 3, bringing the total number of children participating in the survey at

Cycle 3 to approximately 32,000. The analyses in this report draw on different samples of these

children—the complete population, particular birth cohorts, or children with separated parents—

depending on the topic being explored.

Highlights

• The context at birth changed dramatically during the last two decades, with almost one-third

of Canadian children born outside marriage by the turn of the century. Comparing the oldest

and youngest NLSCY children, born in 1983-84 and 1997-98 respectively, shows:

• The proportion of Canadian children born within marriage dropped from 85% to 69%.

1

Throughout the text, unless otherwise clearly indicated, shared custody refers to “physical” custody, with

children living part of the time with each parent. No information is available at the NLSCY regarding shared “legal”

custody, where parents share responsibility for important decisions about the child without necessarily sharing living

arrangements.

- vi -

• More Canadians are choosing to establish their family within a common-law union; the

proportion of children born to cohabiting couples rose from 9% to 22%. Although largely

the result of births in Quebec, there has also been a significant increase elsewhere in

Canada, with proportions doubling in Ontario and the Prairies, and almost tripling in

Eastern Canada.

• Births to single mothers increased from 6% to 10%. In the Atlantic provinces, where

proportions are highest, one in six (16%) babies were born outside a union by 1997-98.

• The proportion of children born within the second family established by their mother or

father rose from 11% among the oldest cohorts to 18% among the youngest.

• The probability of parental separation rose throughout Canada during the 1980s, but leveled

off by the early 1990s.

• The rise was not uniform and created greater variation between the regions.

• Ontario and British Columbia registered the steepest increases during the 1980s.

• Among children born in the late 1980s, the highest proportions with parents separating

before their tenth birthday were found in Quebec (32%) and British Columbia (29%).

• Rising rates of separation and out-of-union births mean more children are experiencing life in

a lone parent family: one-third of the oldest cohorts (1983-84) had lived in a one-parent

family by the age of 15 years, whereas children born just five years (1988-89) later reached

this level by their tenth birthday.

• The 1990s saw a rapid rise in joint custody orders;

2

the proportion of children in shared

physical custody also rose. Although shared physical custody often transforms into sole

custody over time (only 40% of children in shared living arrangements at separation were still

alternating between their parents’ homes in 1998-99), the fact of the change does not hinder

continued long-term involvement of both parents after separation.

• Although children’s participation in the decisions about custody increases with age, many

parents decide not to involve their children in decisions about custody. However, when they

do, their children’s opinion counts.

• More couples separating in the late 1990s appear to reach a child support agreement within a

relatively short period after they separate. However, child support payments were expected for

under two-thirds (63%) of child support agreements reached for children (aged 4-15 years in

1998-99) whose parents separated in that period at the end of the 1990s.

2

Joint custody implies that children’s “legal” custody is shared, giving parents joint responsibility for important

decisions, such as children’s schooling; in some cases of joint custody, parents also share their children’s physical

custody.

- vii -

• When payments are part of the support agreement, they are mostly regular and for the full

amount, at least within a relatively short period (up to two years) after the separation: regular

payments were made for 84% of children, and more than 90% of regular payments were paid

in full.

• Private formal child support agreements are associated with more reliable support payments

than private informal agreements or agreements contained in a court order.

• Shared living arrangements and sole father custody are more common in Quebec than

elsewhere in Canada. Shared custody is also more durable, agreements made about custody

and access are more strictly adhered to, and children are more often consulted about these

arrangements in Quebec.

Implications

Taking a life course perspective on children’s family experience provides new insights with

important policy implications. The pathway into a lone-parent family, for example, is linked to

the type of lifestyle a child is likely to have during the episode, with separated or divorced lone-

mother families having a higher standard of living on average than those established by young

single mothers. With separation rates stabilizing in the early 1990s and out-of-union birth rates

rising, this second entry into single-parent family life is likely to assume a greater relative

importance in the next decade. Important regional differences in out-of-union birth rates means

that a higher proportion of lone-parent families may be in need of financial assistance in some

provinces than in others.

Sharing physical custody, even for a limited period, is associated with continued long-term

involvement with both parents. However, the costs and complexity of shared living arrangements

make it unworkable at times. Qualitative research into the advantages and problems with shared

physical custody is needed, to give parents, mediators and others a better basis from which to

judge whether shared custody is appropriate in any given case.

With the vast majority of child support payments being made regularly and on time, the problem

appears to be in negotiating an agreement rather than its implementation. While the 1997 Child

Support Guidelines have had some success in helping separating couples share financial

responsibilities for their children, the high proportion of couples with no support agreement

shows there is still some way to go. Some parents do not have the means to pay; for others, the

prohibitive financial costs involved when parents fail to agree may mean no child support

agreement is reached. Only qualitative research can throw more light on this question.

Finally, this report has highlighted the distinctive nature of Quebec, not only with regard to

common-law unions but also in relation to the way parental responsibilities are shared at

separation. Is it a result of the different approach to separation and divorce in Quebec law or is it

a social rather than a legal phenomenon? This is an interesting avenue for further research, not

least to discover whether the differences between Quebec and the rest of Canada extend to the

impact of separation on children.

- 1 -

INTRODUCTION

This is the second of three reports examining the impact of parents’ family transitions on

children’s family environment and economic well-being based on longitudinal data from the

National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY), a panel survey conducted jointly

by Human Resources and Development Canada (HRDC) and Statistics Canada.

3

The first report

focused particularly on how changes in the conjugal situation of parents affect the economic

circumstances within which children are raised (Juby, Le Bourdais and Marcil-Gratton, 2003).

The next two reports examine in greater depth how parents’ conjugal behaviour shapes the

family life course of their children. This report focuses specifically on aspects of the most

common family transition for Canadian children, and the first for most of them—their parents’

separation. The third report will explore what happens next as mothers and fathers go their

separate ways.

Two themes, often absent from research on family change, are central to this report. Together

they guide the analyses and provide a backdrop for social policy formulation:

• Children’s family experience needs to be viewed as a “process” that evolves in response

to decisions made by parents about their own conjugal and parental life.

In other words, the concept of “family life course” should replace that of “family structure,” on

which most family research is based. This is due to two main reasons

1. Structure implies solidity or permanence, and leads implicitly to the idea that children spend

their lives in a given family type: intact, lone-parent or stepfamily. As a result, a large body

of research has looked at the impact on children of “growing up” in a lone-parent or

stepfamily, without taking into account that relatively few children do in fact spend their

entire childhood in one of these family types.

2. The family structure perspective groups all families of the same “type” into a single category,

ignoring the events leading up to the formation of the family. This leads to an

oversimplification of reality and to false stereotyping. Take “lone-mother families” as an

example. Taking into account the event immediately preceding the transition to a lone-

mother family reveals two very distinct lone-mother family types: one created when a single

woman has a child outside a union, the other formed when a couple who have had children

together decide to separate. These two types have very little in common with each other. In

the first case, mothers tend to be young, single, and have only one young child; when they

enter a new union, which most do, they generally marry their partner, who becomes the first

and only father the children have ever lived with. In the second case, separated mothers tend

to be older, and have more and older children; a new union starts more often with

cohabitation than marriage, and the new partner arrives in the life of children who lived for

an extended period with their biological father (Juby, Marcil-Gratton and Le Bourdais,

3

For more information on the NLSCY, please consult the Human Resources and Skills Development Canada

(Applied Research Branch of Strategic Policy Section) website at:

http://www.hrsdc.gc.ca/en/cs/sp/arb/contact/contact_us.shtml#nlscy (as of September 2004).

- 2 -

2001). Only by taking a “life-course” approach to children’s family experience is it possible

to provide a more complete picture of the relevant aspects of a child’s family experience.

• More and earlier parental separation means that close and significant family members

do not necessarily live in the same household; the analysis of children’s family

experience, therefore, has to extend beyond the residential group.

Family structure almost always refers to the residential family unit. For intact families this

definition is adequate, as the residential family includes a child’s parents and siblings. For the

growing number of children in other family types, however, limiting the study of the family to

the residential group is problematic. Children may belong to more than one residential group, for

instance. Even if they do not, close family members (most often the father) who continue to play

an important role in their children’s life may not reside in the same household. To study family

life without including these individuals seriously constrains the understanding of a child’s family

experience. NLSCY data makes it possible to identify and include these “non-residential” family

members in many of the analyses conducted here.

In these reports, we attempt to provide a broader perspective on the changing family life

experience of Canadian children. Instead of viewing parents as forming a unit, we look at them

as two individuals whose conjugal and parental life courses meet for a period of time, during

which a child is conceived. The child’s family life course is then dependent on whether or not

parents continue to follow the same path, or whether they decide to go their separate ways—an

event that occurs for some children even before their birth. Subsequently, the child’s family

environment is subject to decisions made separately by each parent—decisions to form or

dissolve new unions, to have additional children in these new unions etc. Appreciating this

diversity is an essential step in designing programs and policies to help children and families

adapt to family transitions in a healthy and positive way.

What is a family transition?

Family transitions are the building blocks of the family life course. In this study, a family

transition is considered to occur when parents change their conjugal status (i.e. they create or

dissolve a marriage or common-law union). In addition, certain “parental status” changes are

also considered as transitions: when the mother or father becomes a “stepparent” at the formation

of a new union with a partner who has children from an earlier union; or when they have a child

with a new partner, providing their children with a half-sibling. Some of these changes have a

direct impact on the child’s residential family group, triggering a transition from one family type

to another: from intact to lone-parent family when parents separate, for example. Others, such as

the arrival of a new partner in the non-custodial parent’s life will not prompt a transition, but will

have an impact on the child’s extended family environment.

In this report, we focus on the beginning of the life course, situating the child’s birth within the

family life course of the parents, and looking at the first and most common transition

experienced by children: their parents’ separation. The report is divided into four sections:

- 3 -

• Section I sets the scene, updating and expanding earlier analyses of how the context within

which children born during the last two decades of the 20

th

century has evolved (see Marcil-

Gratton and Le Bourdais, 1999). Specifically, we examine the evolution of births within or

outside of a union, within marital or common-law unions, and within a first or subsequent

family unit, comparing different cohorts of children and different regions of Canada. This

section also looks briefly at how these factors influence children’s subsequent family life

course transitions.

• Section II updates and expands information relating to parental separation, tracing the

relationship between the context at birth and the likelihood that parents separate, and showing

how this relationship varies through time and for different regions of Canada.

• Section III focuses on the way in which parents divide responsibilities for children when they

separate, with a particular emphasis on shared custody. The different types of shared living

arrangements and the evolution of these arrangements through time are considered.

• Section IV examines the new information collected for the first time at Cycle 3 concerning

custody issues (e.g. whether children are consulted; whether parents keep to the visiting

arrangements agreed upon) and child support arrangements (e.g. whether support agreements

are adhered to; whether support agreements mean that support payments are expected) made

for children when parents separate.

Family and Custody History Data

The retrospective “Family and Custody History” section of the National Longitudinal Survey of

Children and Youth provides complete conjugal and parental histories of each child’s biological

parents up to the time of the first survey, in the winter of 1994-95, and is brought up to date at

each subsequent survey. The family history data gathered in this survey provide a new insight

into the extent to which decisions parents make with regard to their conjugal and parental life

affect their children’s family life course, by making it possible to reconstruct the complex family

networks created by both biological parents after they separate.

However, the wealth of information about the conjugal and parental behaviour of both biological

parents, on which the analyses in this section are based, brings its own problems. Linking such

complex information from one cycle to another is a time-consuming process, made more so by

problems of inconsistency between information reported or recorded at successive surveys. For

example, several separated mothers, who were recorded in the Cycle 1 data file as not living with

a new partner, reported at Cycle 2 that they were not only living with a new partner, but that this

partner had also been present two years earlier (when Cycle 1 data was collected). Verifying

other data revealed that, in most cases, the new partner had arrived in the household shortly

before the Cycle 1 survey, and mothers probably failed to report a new relationship whose

durability was still uncertain at that time. Before starting the research itself, therefore, the first

step involved creating the child samples at Cycles 1 and 2, and validating the data to ensure

consistency between the family information collected at the two cycles.

- 5 -

I THE CHANGING FAMILY ENVIRONMENT AT BIRTH

Changes in marital behaviour have altered radically the context into which children are born, in

ways that are closely connected to how their family life course subsequently unfolds. Until

recently, most children were born to married parents who were both in their first conjugal union;

the only other children within their family environment at birth were full siblings, older than

themselves, and living in the same household. By the end of the 20

th

century, however, the

declining popularity and stability of marriage produced greater variation in the contexts within

which children are born (Marcil-Gratton and Le Bourdais, 1999). Starting a family outside

traditional marriage has become more commonplace, and rising separation and divorce rates

earlier in the family life course means more men and women are having children in more than

one union. The result: growing proportions of children are born outside marriage and into

complex family environments.

In terms of the life course approach used here, this means that children may be born earlier or

later in their parents’ life course, and to parents who may or may not have decided to marry

before their birth. Some are born even before the start of their mother or father’s conjugal life

course, often to young parents who have never lived with each other or with any other partner.

Others, on the contrary, are born much later on, arriving into the second or third family of one or

both parents. Analyses of Cycle 1 data have shown that these factors have an impact on the

child’s subsequent family life course:

• One study revealed that married couples with children are more likely to stay together than

those who are cohabiting, although in Quebec the difference is decreasing (Le Bourdais, Neill

and Marcil-Gratton 2000).

• A second study showed a similar association between union stability and family type at birth

(Juby, Marcil-Gratton and Le Bourdais, 2001). Children born into a “first family” (i.e. a

family created by a couple neither of whom has children from an earlier union) are less likely

to see their parents separate than are those with either maternal half-siblings living in the

family, or paternal half-siblings living elsewhere. This remains true even after controlling for

the fact that second families are more often created by cohabiting couples than are first

families.

Clearly, the context into which a child is born is closely associated with the number and type of

family transitions that occur later on during childhood. Understanding how this context has

evolved in recent years, therefore, is the first step towards appreciating how complex and diverse

the family life course of Canadian children is becoming. Updating and extending analyses from

earlier reports (Marcil-Gratton, 1998; Marcil-Gratton and Le Bourdais, 1999), this section looks

in detail at the evolution of the circumstances surrounding the birth of the NLSCY children,

comparing the experience of different cohorts of children and different regions of Canada. The

parts of this report that relate directly to the family life course experience of these children are

based on information collected from the longitudinal sample of approximately 15,000 children

included in the first two survey cycles, and aged between 2 and 13 years at Cycle 2, carried out

in 1996-97. The other analyses are based on a variety of samples from the first three cycles

depending on the subject under observation.

- 6 -

Married, cohabiting or alone?

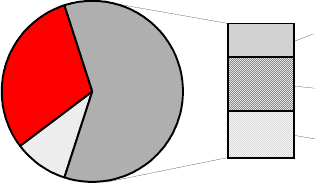

Figure 1.1 shows the distribution of the longitudinal sample of children according to whether or

not they were born within a union, and the legal status of the union:

• More than three-quarters (78%) of children were born to married parents, although 30% of

parents had lived together before marrying.

• Fifteen percent (15%) of children were born outside marriage, but within a union, to

common-law couples.

• The rest (7%) were born to mothers who were not living with their child’s father.

Figure 1.1 Type of parents’ union at child’s birth, for children aged 2-13 years in

1996-97, NLSCY, longitudinal cohort (N=15023)

Marriage - no prior

cohabitation

48%

Not in union

7%

Common-law union

15%

Marriage preceded by

cohabitation

30%

By including all children in the sample, however, this distribution conceals important differences

between the oldest and youngest children in the survey, and between the various regions of

Canada, as the next sections show.

Changes through time

The matrimonial context within which families are established evolved a great deal even during

the relatively small number of years separating the oldest and youngest NLSCY cohorts.

Figure 1.2 presents the distribution by context at birth for the oldest and youngest cohorts of

children in the survey—those born in 1983-84 and in 1997-98.

4

• The proportion of children born within marriage (preceded or not by cohabitation) dropped

from 85% of the oldest children to just over two-thirds (69%) of the youngest.

4

Cohorts included for the first time at Cycle 3.

- 7 -

• The proportion of children born within a common-law union more than doubled, rising from

9% of the oldest children in the survey to 22% of the youngest.

• The proportion of births to single mothers increased from under 6% to 10%.

By the end of the 1990s, in other words, almost one-third of Canadian children were born outside

marriage, although the majority were nonetheless born within a couple, to parents in a common-

law union.

Figure 1.2 Distribution of children according to parents’ conjugal status at the child’s

birth for various cohorts of children, NLSCY, Cycles 1 and 3,

Inter-regional variations through time

60

35

25

34

9

22

6

10

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

1983-84 1997-98

Birth Cohort

%

Direct Marriage Marriage preceded by cohabitation Common-law union Not in union

Figures 1.3a and 1.3b compare five Canadian regions in terms of the evolution of the context at

birth for the oldest and youngest children. Perhaps the most striking feature of the 1983-84

cohorts (Figure 1.3a) is how similar they are from one region to another. In all regions, Quebec

included, at least 80% of children were born to married parents, and under one-tenth were born

outside a union in all but the Atlantic provinces. A few inter-regional differences are visible,

however:

• Ontario and the Prairies were the most “traditional,” in the sense that almost 90% of births

occurred within marriage.

• Births to cohabiting couples were much more common in Quebec (17%) than in any other

region, and out-of-union births much less so (3%).

• The highest proportions of out-of-union births were found in the provinces at the extreme

west and east of Canada—in British Columbia (9%) and the Atlantic provinces (11%).

- 8 -

• These were also the only provinces where children born to a single mother outnumbered those

born to cohabiting parents.

Figure 1.3a Distribution of children according to parents’ conjugal status at the child’s

birth, by region of Canada, 1983-84 cohorts, NLSCY, Cycle 1 (N=3227)

56

60

64

54

59

28

27

24

26

21

7

7

7

17

9

9

6

5

3

11

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

British Columbia Prairie provinces Ontario Quebec Atlantic Provinces

%

Direct Marriage Marriage preceded by cohabitation Common-law union Not in union

Figure 1.3b Distribution of children according to parents’ conjugal status at the child’s

birth, by region of Canada, 1997-98 cohorts, NLSCY, Cycle 3 (N=7894)

33

36

46

19

26

40

39

33

26

35

16

17

11

46

23

11

8

10

9

16

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

British Columbia Prairie provinces Ontario Quebec Atlantic Provinces

%

Direct Marriage Marriage preceded by cohabitation Common-law union Not in union

- 9 -

Less than fifteen years later, the situation had changed in all regions, but towards a greater

variability (Figure 1.3b). By the end of the 20

th

century, regional “patterns” of matrimonial

behaviour were starting to emerge, with the two central regions, Ontario and Quebec,

representing the extremes, at least in terms of the choice of marriage versus cohabitation as the

context for starting a family. Ontario registered significantly more births to couples who married

without living together first (46%) than anywhere else in the country, while Quebec recorded

significantly less (19%). In fact, less than half of all births now occur within marriage in Quebec,

and in some of the most predominantly francophone areas of the province the proportion has

dropped to below one-quarter (Institut de la statistique du Quebec, 2000).

Moving west from Ontario, marriage is still the choice for most couples wishing to start a

family—approximately three-quarters of babies in the Prairie provinces and in British Columbia

are born within marriage, although more than half have parents who had lived together before

marriage. East of Quebec, the situation is very different. In the Atlantic provinces,

5

only

three-fifths of births are marital births, while close to one-quarter of babies are born in a

common-law union. This is second only to Quebec. In other words, while the rise in

common-law union births in Canada is largely the result of births in Quebec, there has been a

significant increase in the phenomenon in all regions, doubling in Ontario and the Prairies, and

almost tripling in Eastern Canada.

The Atlantic provinces have the highest proportion of births to single mothers, with one in

six (16%) babies born outside a union. This last result is unique only in its extent; throughout

Canada (with the exception of British Columbia), the proportion of out-of-union births increased

just as rapidly between the oldest and youngest cohorts. After years of relative stability in the

rate of “out-of-union” births, this rise needs to be interpreted with caution. It does not necessarily

indicate that single-motherhood is becoming more popular. It is more likely the consequence of

two other demographic changes:

• Declining fertility within conjugal unions. In the current context of falling conjugal fertility,

stable rates of out-of-union births result in an automatic increase in the proportion of

out-of-union births.

• A changing age structure of women of reproductive age. Single mothers are usually

young—in their teens or early twenties, while married women have children later on.

A decline in the number of women of the age at which marital fertility is highest relative to

the number of women of the age at which non-marital fertility is highest, automatically entails

a rise in the proportion of out-of-union births.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the steep drop in fertility rates, which could have led to a rising

proportion of out-of-union births, was compensated for by the arrival at the main childbearing

ages of the baby boom generation. During the 1990s, however, the baby boom generation moved

beyond the main childbearing age groups, altering the age structure of women of childbearing

age. The ratio of women aged 15-24 years (highest rates of out-of-union births) to those aged

5

Except in Prince Edward Island where three-quarters of births are within legal marriage and only 6% of births are

to single mothers.

- 10 -

20-34 years (highest rates of in-union births) rose from 55% in 1991, to 59% in 1996 and 66% in

2001.

First or second family?

Earlier and more frequent separation among parents in intact families means that more mothers

and fathers establish a second family with a new partner. In consequence, a growing proportion

of children are born into a family environment that includes older half-siblings—the children

from a previous union of their mother or father. As custody is given to women in the majority of

cases, children from their first family are usually living with mothers when they start a second

family. This means that children born into their mother’s second family are usually born into a

stepfamily—their biological father is the stepfather of their maternal half-siblings. This is less

often the case when fathers start a second family. Most of the children who are born into their

father’s second family live in a residential family unit that includes themselves, their biological

parents and full-siblings. They are born, residentially speaking, into an “intact” family.

Earlier research has shown, however, that children born into their father’s second family have

more in common with children born in stepfamilies than intact families in terms of their

subsequent family life course (Juby, Marcil-Gratton and Le Bourdais, 2001). In this analysis, we

consider that the “context at birth” for this group of children is very different from that of

children born into their parents’ first family; they have therefore been classified separately as

being born into a “quasi-intact” family. Here, we identify four types of two-parent families:

• The term “intact family,” used synonymously with “first family,” is restricted to families

where neither biological parent has had children with another partner. As Figure 1.4 shows,

four out of five children were born into the first family of both parents.

• The rest of the children from two-parent families were born into a “second” family, in that at

least one of their parents already had children from an earlier union. Three types are

considered here:

• “quasi-intact” families (5%): children’s half-siblings are living elsewhere (usually paternal

half-siblings living with their mother);

• stepfather families (5%): children with maternal half-siblings only living in the family;

• stepmother or stepfather/stepmother families (3%): children with paternal half-siblings,

and at times maternal half-siblings, living in the family.

- 11 -

Figure 1.4 Family context at birth, for children aged 2-13 years in 1996-97, NLSCY,

longitudinal cohort (N=14949)

Intact

80%

Stepmother or

Stepmother/stepfather

3%

Lone parent

7%

Stepfather

5%

Quasi-intact -

half-sibs absent

5%

Figure 1.5 illustrates the evolution of this phenomenon for children born within a conjugal union,

comparing the family context at birth for the oldest (1983-84) and the youngest (1997-98)

NLSCY cohorts.

• The proportion of children born within the second family established by their mother or father

rose from 11% to 18%, with a corresponding drop in the proportion of births within a first

intact family, from 89% to 82%.

• Among the youngest cohorts, 11% of children lived from birth in a family that included half-

siblings; another 7% had half-siblings living in another household.

- 12 -

Figure 1.5 Distribution of children born in two-parent families according to the family

context at birth, 1983-84 and 1997-98 cohorts NLSCY, Cycles 1 and 3

89

82

5

7

4

7

4

2

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

1983-84 1997-98

Cohorts

Stepmother or stepmother-stepfather family

Stepfather family

Quasi-intact - half-siblings absent

Intact

Combining these two “situation at birth” variables, Figure 1.6 shows the strong relation between

the increasing popularity of common-law unions and the rise in second families. It shows:

• Couples who choose to marry without living together first are generally in their first union

and rarely have children from an earlier union. As a result, more than half the children born in

an intact family (56%) had parents who had married without living together first, compared

with less than one-fifth of children born in other two-parent family types.

• Cohabitation is the union of choice for establishing a second family. Four-fifths of children

born in a stepfamily were born to parents who had cohabited; more than half the time, parents

were still cohabiting when they were born. As a result, 43% of children born in a stepfather

family, and 48% in other stepfamily types, were born outside marriage.

• Quasi-intact families (with half-siblings not living in the family) are closer to stepfamilies

than to intact families in terms of the type of parents’ union at birth.

- 13 -

Figure 1.6 Distribution of children, aged 2-13 years in 1996-97, born in two-parent

families by family context and by type of parents’ union, NLSCY, Cycle 2,

longitudinal cohort (N=13870)

56

19

18

20

32

44

40

32

13

36

43

48

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Intact Quasi-intact Stepfather Stepmother or

Stepmother/stepfather

Family context at birth

Direct Marriage Marriage preceded by cohabitation Common-law union

The context at birth and family transitions

How are these different birth contexts associated with the way the family life course unfolds

during childhood? How are they linked to the likelihood that children experience radical change

in their family environment? By the second NLSCY cycle in 1996-97, almost one-quarter of

children (24%) in the longitudinal sample had already experienced at least one family transition

even though, at an average age of just under eight years, they were still relatively young. For the

vast majority of children—those born within a conjugal union—their parents’ separation marks

the first transition. For the 7% of children whose parents were already “separated” at their birth,

the formation of a conjugal union is the first transition, either when their parents start living

together, or when their mother or father enters a union with someone else.

Evidently, the younger children are, the less time they have had to live a family transition. As

Table 1.1 shows, 18% of pre-school children had lived some change in their family situation

between their birth and Cycle 2; the proportion rose to 26% among children aged 6-9 years,

reaching 28% among children aged 10-13 years. Differences would be even larger were it not for

the increase in separation during the 1980s which affected the younger cohorts more than the

older ones.

However, age is not the only factor that raises the probability of experiencing family change. The

context within which children are born also appears to have an influence on children’s family life

course. Table 1.1 indicates that the proportion of children who had already lived at least one

family transition by 1996-97 varied considerably according to their parents’ conjugal status:

- 14 -

• Among children whose parents had married without prior cohabitation, one child in eight

(12%) had experienced a family transition.

• This proportion rose to 20% for children whose parents had cohabited before marrying.

• It more than doubled (44%) among children born in a common-law union.

• The difference between marriage and common-law unions is particularly marked in the early

years. Among children aged 2-5 years in 1996-97, the proportion with separated parents was

five times higher among children born to cohabiting parents than among children born to

married parents with no previous cohabitation.

• Over three-quarters of children born outside a union experienced some change in their family

environment. This high proportion is due to the different nature of the first transition for this

group: parents who are already “separated” at their child’s birth are more likely to enter a

union than couples, especially parents, are to terminate theirs.

Table 1.1 Proportion of children aged 2-13 years in 1996-97 who have experienced at

least one family transition, by age group, and according to a) the parents’

conjugal status and b) the family context at the child’s birth, NLSCY,

longitudinal cohort (N=14940)

a) By conjugal status of parents at child’s birth

In a conjugal union

Child’s age

at survey

Direct

marriage

Marria

g

e preceded

by cohabitation Common-law Total

Not in

a union

Total

2-5 years 5.9 11.2 33.6 13.8 62.0 17.6

6-9 years 11.8 21.7 48.7 21.3 82.1 26.1

10-13 years 17.2 28.0 54.2 24.6 86.2 27.9

Total 12.3 19.9 43.6 20.0 75.7 23.9

b) By family context at birth (children born in a two-parent family)

Child’s age

at survey Intact

Quasi-intact (half-

siblings absent) Stepfather

Stepmother or

Stepmother/

stepfather Total

2-5 years 11.7 28.4 27.8 25.2 13.8

6-9 years 17.7 43.5 40.1 43.4 21.3

10-13 years 21.2 45.7 59.0 38.5 24.6

Total 17.0 39.8 41.1 36.1 20.0

The second part of Table 1.1 confirms that the point at which children arrive in their parents’

family life course is linked to their own experience of family change: the percentage of children

born in a second family experiencing their parents’ separation is much higher than among

children born in a first family. Compared with children born in intact families (17%), children

from quasi-intact families (whose half-siblings do not live in the household—40%), and from

stepfather families (whose maternal half-siblings are present in the household—41%), are

particularly likely to have lived a family transition between birth and 1996-97.

- 15 -

These figures represent the combined experience of children of different ages and from different

parts of Canada. They do not indicate whether children from more recent cohorts, or from

regions with high proportions of common-law union births, are more likely to experience their

parents’ separation. The next section examines in greater detail the most common family

transition, and the first in the lives of most children: their parents’ separation.

- 17 -

II SPLITTING UP

Children can take different pathways into their first lone-parent family episode: they may be born

into it, or arrive there at some point during childhood when their parents separate or, more rarely,

when a parent dies. As mentioned earlier, the pathway has a strong influence on their experience

of lone-parent family life and on their subsequent family trajectory. An earlier report

documented the rapid rise, during the 1970s and 1980s, in the proportion of children

experiencing life in a lone-parent family and at an increasingly early age (Marcil-Gratton and

Le Bourdais, 1999). Increasing rates of separation and divorce among parents establishing

families during this period was the principal motor of change; data from Cycle 3 of the NLSCY

makes it possible to update this information and evaluate whether this trend continued among

children born in the early 1990s. It is too early, however, to assess what additional impact the

growing proportion of children born to a lone parent during the late 1990s will have on the

overall risk of lone-parent family life, as children from these cohorts are still too young to have

experienced their parents’ separation.

For the sake of clarity, we separate the two pathways into lone-parent family life, restricting the

first analysis to the most common entry, via parental separation. We then expand the analysis to

include the other pathways into lone-parent family life, through the death of a parent or through a

birth outside a union. In both cases, we compare the experience of children from the oldest

NLSCY cohorts (born in 1983-84), with that of children born five years later (1988-89) and ten

years later (1993-94), up to the age of 15, 10 and 5 years respectively. Trends are then examined

for Canada as a whole and for the different regions.

Recent trends in separation

Figure 2.1a presents the cumulative proportion

6

of Canadian children, born within a marital or

common-law union, who experience their parents’ separation. Comparing the different cohorts

shows:

• By the age of 15 years, almost 30% of children born within a couple during the early 1980s

had experienced their parents’ separation, 25% of them by the age of 12 years.

• Children born only five years later, in 1988-89, reached this level (one-quarter with separated

parents) three years earlier, at around the age of 9 years.

• The rapid rise in separation during the 1980s leveled off by the early 1990s, with the 1993-94

cohorts having a similar experience to that of the 1988-89 cohorts, at least during the pre-

school years.

6

Calculated using the Life Table Method, a mathematical model used to describe lifelong events experienced by a

cohort. A key advantage when applied to retrospective data is the possibility of including incomplete life histories of

cohort members.

- 18 -

Figure 2.1a Cumulative proportions of Canadian children who experienced their

parents’ separation, various birth cohorts, NLSCY, Cycle 3 (life table

method)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

02468101214

Age of child

%

1993-94 cohorts 1988-89 cohorts 1983-84 cohorts

Figure 2.1b Cumulative proportions of Canadian children born to a lone parent or

experiencing their parents’ separation, various birth cohorts, NLSCY,

Cycle 3 (life table method)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

02468101214

Age of child

1993-94 cohorts 1988-89 cohorts 1983-84 cohorts

- 19 -

Life with a lone parent

For children born within a union, their parents’ separation almost always marks the beginning of

an episode in a lone-parent family. The growing minority of children born to a single mother also

start life in this type of family. Figure 2.1b presents the cumulative percentage of children who

experience a first episode in a lone-parent family, either because they were born outside a

conjugal union, or following their parents’ separation, once again comparing the experience of

older and younger children.

The curves are similar to those in Figure 2.1a, but start at a higher level due to the proportion of

children born outside a union and therefore living in a lone-parent family from the start (age 0

years).

• Altogether, by the age of 15 years, one third of the oldest cohorts had lived in a one-parent

family at some point, 30% by the time they entered their teens.

• Children born at the end of the 1980s reached similar levels approximately five years earlier

(at 10 and 8 years).

• Once again, the youngest cohorts included here followed a similar path during early

childhood to that taken by the 1988-89 cohorts.

Differences by province

The last section suggests a widening gap between the different regions of Canada with regard to

the matrimonial context within which families are established. Do these differences extend to the

durability of the family units within which children are born? Is separation more common in

regions in which marriage has lost the most ground? The cumulative proportions of children

whose parents separated by their tenth birthday are presented in Figure 2.2a by region of Canada.

The experience of children born between 1983-85 is compared with that of those born only six

years later, between 1989-1991. This comparison shows:

• Only Quebec stands out from the other provinces in the earlier cohorts (1983-85), with over

one quarter of children born within a union experiencing their parents’ separation by their

tenth birthday. This compares with between 16-20% in the other regions.

• The probability of separation rose throughout Canada during the 1980s. However, the rise was

not uniform and created greater variation between the regions:

• Ontario registered the steepest increase, with a more than 50% rise in the probability of

separation.

• The other sharp increase was in British Columbia, leaving it (at 29%), second only to

Quebec (32%) in terms of how frequently, and how early on in their children’s lives,

parents separate.

- 20 -

• The Atlantic and Prairie provinces were the only regions that had not caught up with

Quebec’s 1983-85 levels by 1989-91. They were the only areas in which children born in a

union still had a three in four chance of living with both parents at their tenth birthday.

Figure 2.2a Cumulative proportions of children who have experienced their parents’

separation by age 10 years, by region of Canada, 1983-85 and 1989-91 birth

cohorts, NLSCY, Cycle 3 (life table method)

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

British Columbia Prairies Ontario Quebec Atlantic Provinces

1983-85 cohorts 1989-91 cohorts

In addition to the proliferation of births to cohabiting couples in the 1980s, the previous section

also showed growth and provincial variations in the rate of out-of-union births—the second

gateway into life in a lone-parent family. Figure 2.2b shows how adding this alters the image of

lone-parent family life given when parental separation alone is considered. First, including

out-of-union births raises the probability of life with a lone-parent across the board. Among the

1983-85 cohorts, at least one-fifth of children had already lived with one biological parent by the

age of ten years in all regions. In British Columbia, Quebec and the Atlantic provinces, this was

the case for more than one-quarter of children.

- 21 -

Figure 2.2b Cumulative proportions of children who have experienced a lone-parent

episode by age 10 years, by region of Canada, 1983-85 and 1989-91 birth

cohorts, NLSCY, Cycle 3 (life table method)

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

British Columbia Prairies Ontario Quebec Atlantic Provinces

1983-85 cohorts 1989-91 cohorts

Beyond this, however, it is interesting to note that the addition of out-of-union births reduces

inter-regional variations considerably, as a high proportion of out-of-union births in some

regions compensates for low rates of separation, and vice versa.

• Among the more recent cohorts (1989-91), three children in ten experienced life with a lone

parent before their tenth birthday in all Canadian regions.

• Children born in British Columbia had the highest probability (36%), overtaking Quebec

(34%).

• Despite its relatively high conjugal stability, high rates of out-of-union births meant that

one-third of children born in the Atlantic provinces also experienced lone-parent family life

by the age of ten years.

This analysis shows clearly that, although the vast majority of children are still born within a

conjugal union, the proportion of children spending their entire childhood with both biological

parents fell rapidly during the 1980s and remained at this level in the following decade. Many

children share a residence with both parents for only the first part of their childhood, and the

duration of this episode also declined rapidly during the period. Despite the leveling off of

separation rates during the 1990s, the rise in the proportion of out-of-union births suggests that

the proportion of children experiencing life in a lone-parent family will continue to rise.

- 23 -

III SHARING CUSTODY

One of the most challenging issues faced by separating parents is how to share the physical care

and economic support of their children. Are the children to live with the mother or the father

after separation, or will each parent create a family home and have the children with them part of

the time? Who will be responsible for the financial cost of raising the children now that the

household income that previously supported one household is shared between two? Reaching an

agreement in the emotionally charged climate that surrounds most couples in the throes of

separation is not easy. Nonetheless, many parents come to an agreement between themselves,

with or without what may be costly legal involvement. At other times, they are unable to agree

and the court imposes a solution based on what is perceived to be in the best interests of the

child.

The divorce statistics collected by Statistics Canada, the only national data source on how

parents organize care after separation before the NLSCY, suggest a trend towards greater

diversity in custody arrangements. Based on this information, Figure 3.1 illustrates how custody

arrangements have evolved for minor children whose custody was included in a court order from

just after the 1968 Divorce Law up to the year 2000.

• Despite minor fluctuations during the 1970s and 1980s, the proportion of children put into

mother, father or joint custody in 1990 was almost identical to that of 1970, with sole mother

custody granted for just under three-quarters of children, and the rest divided fairly evenly

between father and joint custody.

• The 1990s saw a rapid rise in the popularity of joint custody; by the year 2000, well over

one-third of children (37%) were placed in the custody of both divorcing parents. Sole father

custody, on the other hand, actually declined during the period, from around 15% to under

10%. These changes meant that, by the year 2000, sole mother custody was awarded for only

just over half the children concerned.

- 24 -

Figure 3.1 Distribution of minor children for whom there was a custody order at

divorce, according to the type of arrangement, Canada, 1970-2000

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000

Year

%

Mother's custody Father's custody Joint custody

Source: Statistics Canada catalogues: 82-003—vol.2 no.1, Table 2 (1970-1985); vol.3 no.4 (1990); cat. 84-213

(1995, 2000)

However, divorce statistics provide an indication of legal custody rather than actual living

arrangements. Although joint custody means that separated parents continue sharing all the

major decisions concerning their children, it does not necessarily mean that they share their

children’s physical custody. Consequently, unlike sole custody, where children generally live

with the custodial parent, joint custody covers a variety of living arrangements. These statistics

are also limited in terms of the information they provide on the way parents share children’s

living arrangements after separation in two ways:

• First, by referring only to divorce, they provide no information on custody arrangements

reached by cohabiting couples or by married couples who separate but do not divorce.

• Second, not all divorces including minor children are covered by these statistics; custody

arrangements settled privately prior to divorce are not always entered on the divorce record.

By collecting information on all types of separation, and on both legal custody arrangements and

actual living arrangements, the NLSCY made it possible to fill in these gaps (see Marcil-Gratton

and Le Bourdais, 1999). One drawback with the Cycle 1 data used in earlier analyses, however,

was that only children up to the age of 11 years were included. By the third cycle, in 1998-99,

the oldest cohorts of children had reached the age of fifteen years which, coupled with samples

of young children added at each cycle, made it possible to include a wider age range of children

(0-15 years). In this section, we use this sample to extend the analysis of the evolution of custody

arrangements through time, with particular reference to shared custody; in the rest of the text,

- 25 -

shared custody refers to shared physical custody, and is used synonymously with “shared living

arrangements.”

At the NLSCY, separated parents were asked whether there was a court order concerning the

child’s custody; they were then asked specifically if the court order had placed the child in

shared physical custody. However, an earlier analysis of Cycle 1 data (Marcil-Gratton and

Le Bourdais, 1999, Table 7) showed that this still did not mean that children had shared living

arrangements, either at separation or later on. In fact, among children aged 0-11 years, under

one-quarter of children with shared custody as part of the court order actually lived part of the

time with each parent. More than two-thirds lived exclusively with their mother at separation,

and 11% exclusively with their father. The analysis also showed that:

• Under half the children had a court order

7

concerning custody arrangements.

• Shared living arrangements were more frequent when custody was settled privately.

In Table 3.1, these figures are compared with estimates made for all separations experienced by

the broader sample of children, aged 0-15 years in 1998-99. Among children with custody

arrangements contained in a court order, shared custody increased (up from 12.6% in 1994-95 to

17.1%), as did the proportion of these children actually sharing living arrangements (from 2.6%

to 5.6%). These figures confirm, nonetheless, the tenuous relationship between shared physical

custody included in a court order and actual living arrangements:

• Only one-third of children for whom shared custody was granted actually shared living

arrangements between parents at separation.

• Children were considerably more likely to live in shared custody when parents came to an

agreement without legal intervention (11.6%) than with it (5.6%).

7

Settled or in progress.

- 26 -

Table 3.1 Distribution of children with separated parents in 1994-95 and 1998-99,

according to type of custody and living arrangements at separation, NLSCY,

Cycles 1-3

Court order No court order

Custody

order

Living

arrangements

Living

arrangements

Total

Children aged 0-11 years in

1994-95

• Mother

80.8 89.5 86.1 86.8

• Father

6.6 7.9 5.4 7.0

• Shared

12.6 2.6 8.5 6.2

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

N 1215 1730

3276

a

Children aged 0-15 years in

1998-99

• Mother

77.7 88.0 82.0 85.0

• Father

5.2 6.4 6.4 6.5

• Shared

17.1 5.6 11.6 8.5

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

N 2060 2142

4407

b

a

Includes 331 children with a court order in progress at Cycle 1.

b

Includes 205 children with a court order in progress at Cycle 3.

Although children are still far more likely to remain in their mother’s physical care when their

parents separate, this comparison suggests some movement towards a greater equality in sharing

children’s physical care after separation. In the next section, we look more closely at the question

of whether the trend towards increased father involvement after separation, suggested by the rise

of joint custody in the divorce statistics, is also reflected in children’s living arrangements after

separation. We will then explore which forms of shared living arrangements (alternating weeks,

etc.) are most commonly selected by parents sharing custody, and how these arrangements

evolve over time.

Are more children living in shared custody when parents separate?

The divorce statistics presented earlier indicate a rapid increase in joint custody throughout the

1990s; the information in Table 3.1 suggests that this trend extends to actual living

arrangements, though to a lesser extent. Figure 3.2 compares living arrangements made at

separation for children whose parents separated in the early 1990s (1992-94) with those

separating in the late 1990s (1996-98); results appear to confirm this trend. In the four-year

period dividing the two interviews, the proportion of children in shared living arrangements rose

from 9% to 13%, while the percentage of children in their mother’s custody dropped from 85%

to 78%.

- 27 -

Figure 3.2 Distribution of children whose parents separated in the two years preceding

Cycles 1 (1994-95) and 3 (1998-99), according to the living arrangements at

separation, NLSCY

85

78

4

8

7

9

2

4

3

1

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

1994-95 1998-99

With father

Shared - mainly father

Shared equally

Shared - mainly mother

With mother

(Children aged 0-11 years) (Children aged 4-15 years)

However, with mother custody most common among younger children, and other forms of

custody more common later on, it is possible that the older age of the 1998-99 sample explains

this evolution. We used multinomial logistic regression techniques to evaluate how far children’s

age, as well as a number of other variables, explains the apparent trend towards greater diversity

of living arrangements. The model assesses the likelihood that children live in shared custody or

with their father rather than residing with their mother when parents separate, and the results, in

the form of odds ratios are presented in Table 3.2.

8

8

Odds ratios greater than 1 indicates that the category in question increases in the likelihood of the event occurring

compared with the reference category, which is always equal to 1; odds ratios below 1 decreases the likelihood. For

example, in Table 3.2, children in Quebec are more than twice (2.45 times) as likely to be in shared rather than

mother custody than children living elsewhere in Canada.

- 28 -

Table 3.2 Impact of given variables on the probability that children (aged 0-15 years in

1998-99) live in shared custody or with their father rather than remaining

with their mother when parents separate, NLSCY, Cycle 3

(Multinomial logistic regression odds ratios

1

—N = 4377)

Living arrangements (with mother)

Variables

Shared With father

Child’s age at separation

1.143*** 1.198***

Year of separation

• (Before 1991)

1.000 1.000

• 1991-1994

1.153 .858

• 1995-1998

1.487* .650*

Type of agreement

• (Court order, or in progress)

1.000 1.000

• No court order

1.874*** .958

Sex of child

• (Boy)

1.000 1.000

• Girl

.930 .861

Region of Canada

• (Canada, excluding Quebec)

1.000 1.000

• Quebec

2.450*** 1.334*

Reference category given in parentheses.

1

Coefficients significant at: ***p<.001; **p<.01; *p<.05.

The model confirms the great importance of children’s age at separation in the choice of living

arrangements, with both shared and sole father custody significantly more likely among older

children. It also confirms an increase in the popularity of shared living arrangements during the

1990s. Even controlling for age, children whose parents separated in the second half of the

decade were significantly more likely to share time between the homes of both parents than those

whose parents separated during the 1980s. This was all the more likely when parents reached a