University of Nebraska at Omaha University of Nebraska at Omaha

DigitalCommons@UNO DigitalCommons@UNO

Student Work

5-2002

Assessing toddlers' problem-solving skills using play assessment: Assessing toddlers' problem-solving skills using play assessment:

Facilitation versus non-facilitation Facilitation versus non-facilitation

Leslie J. McCaslin

University of Nebraska at Omaha

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork

Part of the Psychology Commons

Please take our feedback survey at: https://unomaha.az1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/

SV_8cchtFmpDyGfBLE

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

McCaslin, Leslie J., "Assessing toddlers' problem-solving skills using play assessment: Facilitation versus

non-facilitation" (2002).

Student Work

. 291.

https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/291

This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by

DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for

inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator

of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please

contact [email protected].

ASSESSING TODDLERS’ PROBLEM-SOLVING SKILLS

USING PLAY ASSESSMENT: FACILITATION VERSUS NON-FACILITATION

An Ed.S. Field Project

Presented to the

Department of Psychology

and the

Faculty o f the Graduate College

University o f Nebraska

In Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree

Specialist in Education

University of Nebraska at Omaha

by

Leslie J. McCaslin

May, 2002

UMI Number: EP72935

All rights reserved

INFORMATION TO ALL USERS

The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.

In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript

and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed,

a note will indicate the deletion.

UMI

Dissertation Publishing

UMI EP72935

Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author.

Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC.

All rights reserved. This work is protected against

unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code

ProQuest LLC.

789 East Eisenhower Parkway

P.O. Box 1346

Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346

EDS FIELD PROJECT ACCEPTANCE

Acceptance for the faculty o f the Graduate College,

University o f Nebraska, in partial fulfillment o f the

requirements for the degree Specialist in Education,

University o f Nebraska at Omaha.

Committee

Chairperson ^ 2 2

ASSESSING TODDLERS’ PROBLEM-SOLVING SKILLS

USING PLAY ASSESSMENT: FACILITATION VERSUS NON-FACILITATION

Leslie J. McCaslin, Ed.S.

University of Nebraska

Advisor: Lisa Kelly-Vance, Ph.D.

Play assessment is rapidly emerging in the field o f cognitive assessment in young

children. One aspect o f play assessment involves the identification o f the types and

levels o f problem-solving skills children possess. Information about a child’s degree of

problem-solving skills could aid school psychologists in understanding the child’s level

o f cognitive development. Research in the area o f play assessment has not focused as

much attention on problem solving as it has on other components o f play. More research

is needed in order to determine if a free play session or an adult-facilitated session is

better for assessing a child’s problem-solving skills using play assessment. The purpose

o f the present study was to identify differences in problem-solving behaviors when

assessment takes place in a nonfacilitated versus a structured facilitated play assessment

session. Twenty children ages 18-48 months were observed playing in either a structured

facilitated or a nonfacilitated setting. It was expected that differences in the level o f

problem-solving behaviors would exist between the two types o f play sessions and that

certain toys would elicit more problem-solving behaviors than others. Results indicated

that there was not a significant difference in the level o f problem solving exhibited by

children in the facilitated or the nonfacilitated sessions. Considerations for future

research are discussed.

Acknowledgements

1 would like to thank my chairperson, Dr. Lisa Kelly-Vance, for her guidance and

support with my project as well as throughout my graduate career. I would also like to

thank Dr. Brigette Ryalls and Dr. Kathy Coufal for their participation as committee

members for the project.

Furthermore, I owe a special thank you to all o f the members o f the play

assessment team who helped in the process o f data collection and recruitment of

participants, especially Jane King. I was fortunate to be able to work closely with Jane,

as the nature of our projects allowed for us to collect data together. My project would not

have been successful without Jane’s organization and her help in recruiting participants,

scheduling data collection sessions, and keeping me focused.

Most o f all, thank you to my husband, Tom. His patience, guidance and support

throughout these past years has helped me accomplish my goals more than he will ever

know.

Table of Contents

I. Introduction/Literature Review

................................................................................

1

A. Contributions to School Psychology

...................................................................

1

B. Early Childhood Assessment

...............................................................................

2

C. Play Assessment

....................................................................................................

4

D. Problem Solving in Young Children

....................................................................

8

E. Facilitation in Play Assessment

..........................................................................

12

F. Problem Solving and Facilitation

..........................................

.

............................

15

G. Summary

........................................................................................................

16

H. The Present Study

..............................................................................

>

.................

16

II. Method

..........................................................................................................................

18

A. Participants

............................................................................................................

18

B. Setting

...................................................................................................................

19

C. Measures

..................................................................................................

.

............

20

D. Procedures

..................................

20

1. Nonfacilitated Group

.....................................................................................

21

2. Structured Facilitated Group

...............................................................

21

3. Coding

.............................................................................................................

21

4. Interrater Reliability

......................................................................................

22

5. Data Analyses

.................................................................................................

22

III. Results and Discussion

...............................................................................................

23

A. Limitations/Considerations for Future Research

..............................................

26

B. Summary

...............................................................................................................

31

IV. References

.....................................................................................................................

33

V. Appendices....

.................................

,

.........................................................

*

................

38

VI. Table..,

...........................................................................................................

41

1

Assessing Toddlers’ Problem-Solving Skills

Using Play Assessment: Facilitation versus Non-Facilitation

Play assessment is rapidly emerging in the field o f cognitive assessment of

preschool-aged children. Children’s play is a natural reflection o f cognitive

development. Practitioners can look toward play behaviors to gain knowledge about a

child’s level o f development. One aspect of play assessment involves the identification

of the types and levels o f problem-solving skills children possess. Malone and Langone

(1999) expressed that there has not been enough attention devoted to researching

behaviors in the context o f play. Further, research in the area o f play assessment has not

tended to focus as much in the area o f problem solving as it has in other components o f

play. Within the framework o f play assessment, researchers should determine the

optimal conditions under which to assess problem-solving skills. For example, if it is

determined that some children are more apt to display problem-solving behaviors in a

structured, facilitated play session rather than in a free play session, then perhaps the

assessment should include a structured, facilitated component in order to effectively

assess the child’s problem-solving skills. The purpose o f the present study was to

provide information about the type o f play setting that should be used in a play

assessment when practitioners are interested in the problem-solving component of play.

Contributions to School Psychology

One role o f the school psychologist is to provide early childhood assessment

when developmental delays are suspected in preschool-aged children. Standardized tests

are not always representative of the potential capabilities o f a young child, especially if

2

the child is disabled or disadvantaged. Play assessment could be used as an

accompaniment to traditional standardized measures of assessing cognitive development

in preschool-aged children. Observing a child’s play behaviors in a natural, non

threatening environment can provide a practitioner with information about the child’s

level o f cognitive development in general as well as compared to the developmental level

of his or her peers. School psychologists working with elementary children can use

findings from preschool play assessments to help them determine the reasons children

may have been eligible for services before they started school (Ross, 2002). In particular,

information about a child’s problem-solving skills is important to the school

psychologist’s understanding of the child’s level of cognitive development. Children

need adequate problem-solving skills to generalize problem solutions to other problems,

to gather information from several situations and experiences and use that information to

solve a new problem, and to generate alternative ways to solve a particular problem

(Chen, Sanchez, & Campbell 1997). In order to conduct a thorough assessment and

design effective interventions, the school psychologist should consider the child’s

competency in solving problems once this aspect of the child’s cognitive fiinctioning is

known. The present study contributes to the field o f school psychology and early

childhood assessment by adding to the research on the specific aspect of problem solving

as it is evaluated using play assessment.

Early Childhood Assessment

Assessment can be used in the preschool years to determine if early intervention

services are needed to prevent childhood problems. This, in turn, may prevent later

3

problems (Lidz, 1977). When a parent or physician is concerned that a child is not

developing in some capacity at an appropriate rate, it is necessary for school

psychologists and other early childhood specialists to verify (or refute) these concerns

and provide assistance with early interventions to try to alleviate or diminish future

problems the child might otherwise encounter as a result o f his or her developmental

delays. The need for effective early childhood assessment has increased since the

passage o f Public Law 99-457 in 1986 that required at-risk children aged three to five to

receive assistance through the public school system. More recently, the Individuals with

Disabilities Education Act, 1997 (IDEA 97), was revised to include infants and toddlers

from birth through age two in the early education requirements.

Common instruments that are used in the United States to assess the cognitive

functioning of preschoolers are the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale: Fourth Edition (S-

B IV) (Thorndike, Hagen, & Sattler, 1986), the Differential Ability Scales (DAS) (Elliott,

1983), and the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale o f Intelligence — Revised (WPPSI-

R) (Wechler, 1989). A primary purpose of such standardized tests is to assess a child’s

need for special services (Salvia & Ysseldyke, 2001).

Now that schools are focusing more on the needs o f preschool-aged children,

school psychologists must find reliable and valid methods of assessing the cognitive’

functioning of these children, a task which is sometimes difficult in cases involving

young children with handicaps (Schakel 1986). Many standardized tests offer normative

data as well as strong reliability and validity measures, but often the tests cannot be

adapted to meet the needs o f exceptional children. Furthermore, standardized testing has

4

received much criticism due to its limitations. Some o f the limitations are as follows: (a)

testing generally does not occur in the child’s natural setting, (b) the test results are not

appropriate for use in monitoring progress or designing interventions, and (c) the tests are

often normed on a population o f typically developing subjects, making assessment of

cognitively delayed children difficult. Criticisms o f standardized tests also focus on the

difficulty in determining whether the tests really measure the constructs they are

supposed to measure and the uncertainty about whether standardized tests are appropriate

for assessing preschool-aged children (James & Tanner, 1993). In addition, standardized

tests often lack predictive and concurrent validity, which renders them inappropriate for

assessing preschool children (Neisworth & Bagnato, 1992).

Play Assessment

Fortunately, many researchers and practitioners realize the limitations o f using

standardized testing to assess preschool-aged children and are working toward finding

more reliable and valid alternatives. One alternative currently in its infancy, although

gaining attention in the literature, is play assessment. Because play is a non-threatening

and natural activity (Lowenthal, 1997), the child is likely to exhibit behaviors during play

assessment that are typical for that child. In contrast, the child is not as likely to exhibit

typical behaviors during a standardized testing procedure in which the child is providing

responses to more structured, rigid questions or tasks with which the child is unfamiliar.

The theoretical roots of play assessment originated in the models of cognitive

development proposed by Piaget and Vygotsky. Piaget (1962) proposed a four-stage

model o f cognitive development. He distinguished among types of play that emerge

5

during the early stages. In the first stage the child forms schemas o f events that can be

later applied to new situations. Grasping, shaking or moving objects are examples of

play behaviors a child might exhibit during this stage. As the child learns to apply

existing schemas to new situations, play becomes more functional. Symbolic play

emerges during the second period, followed by more realistic symbolic play. Vygotsky

(1966) also subscribed to the stage-like notion o f play. He believed that play is a

purposeful activity and that a child develops through play, using play as a means to learn

about the environment and to eventually apply this learning to reality.

In general, play assessment involves observation o f the child’s behaviors while

playing in a naturalistic setting in order to collect information about the child’s

development and cognitive functioning across several domains (e.g., early object use and

symbolic play). The level and category o f play the child exhibits is coded. The codes are

hierarchical such that a higher play code indicates a higher level o f cognitive functioning.

In addition to several core domains such as exploratory or symbolic play, information can

be obtained about behaviors in supplemental domains, including information about the

child’s ability to problem solve. Play assessment is a broad term that describes several

measures that assess play in ways that are unique to each measure. Just as there are many

different types of standardized intelligence tests, several types o f play assessment also

exist (Athanasjou, 2000).

One type Of play assessment is the Play Assessment Scale (PAS), developed by

Fewell (Athanasioii, 2000). The PAS was designed to be used with children ages 2 ter 36

months. Each play Session consists of the child engaging in spontaneous play afid is

6

followed by a segment in which the child is prompted to play with specific toys or

respond to specific verbal and/or motor items. Another type of play assessment,

Transdisciplinary Play-Based Assessment (TPBA), developed by Linder (1993), involves

a diverse team o f people involved with several different aspects of the child’s life.

Transdisciplinary refers to the idea that a team o f people from several disciplines ate

involved in the assessment o f the child, including educators and parents. The

involvement o f parents and several disciplines in the school is an advantage over

standardized testing because people that are familiar with the child across many settings

can provide input about the child’s needs. Several different aspects o f the child’s

behaviors are observed as part o f TPBA. The child is observed during free play as well

as facilitated play, and interactions are observed between the child and a peer as well as

between the child and a parent. Each team member is involved in observing the child and

is subsequently involved in making educational decisions for the child.

Transdisciplinary play-based assessment formed the basis for the development of

the Play Assessment o f Cognitive Skills Scale (PACSS) (Kelly-Vance et al., 2000).

PACSS has evolved into a scale that uses a much more specific coding scheme than

Linder’s. The PACSS observation sessions also differ from TPBA in that observation

sessions using PACSS are limited to a free play session followed by a facilitated segment

in which the child is prompted to play with specific items he or she did not play with

while engaged in free play (Ryalls et al., 2000).

Practitioners have widely .accepted the use of play assessment as a means o f

assessing preschool-aged children (Myers, McBride, & Peterson, 1996). Unfortunately,

7

the flexibility involved in play assessment often lends itself to subjectivity in conclusions

drawn from observation, which can affect scores based on the person rating the

behaviors. Kelly-Vance, Needelman, Troia, and Ryalls (1999) found that 2-year-olds

who were assessed using a modified form of TPBA, Play-Based Assessment, and also

using the Bayley Scales o f Infant Development-II (BSID-II) scored higher on the Play-

Based Assessment than on the BSID-II. Kelly-Vance et al. noted that the children may

have been able to perform better during play because the play sessions did not involve the

restricted format of the BSID-II; however, the authors also noted that the data from the

Play-Based Assessment could have been more influenced by the rater due to the

assessment’s subjectivity.

Farmer-Dougan & Kaszuba (1999) took steps to minimize the subjectivity

involved in assessing play behaviors and to establish the reliability and validity o f play

assessment. A classroom-based play observation system was used as the play assessment

in their study, which consisted o f 42 children ages 3 to 5. The Battelle Developmental

Inventory (BDI) was used to obtain standardized scores of each child’s cognitive ability.

In addition the Social Skills Rating Scale - Teacher Form (SSRS-T) was used to measure

the children’s social skills. Play categories were defined in terms o f social play and

cognitive play. The children were videotaped playing over four 10-minute periods, and

four independent observers later coded their play behaviors. The observers coded until a

minimum interrater reliability of .90 was established. Results indicated that the

children’s play behavjprs predicted their scores on both the BDI as well ^sthe$SR $-T.

These results strengthened the credibility o f play as a viable assessment tool as long as

8

play categories are operationally defined. The present study adds to the limited amount

o f research available regarding the effectiveness o f using play assessment to measure the

cognitive development in preschool-aged children by looking specifically at children’s

problem-solving skills.

Problem Solving in Young Children

Within the area o f play assessment, a child’s ability to problem solve reflects the

child’s level o f overall cognitive functioning. Research indicates that problem-solving

skills develop early in childhood. Infants as young as 6 months of age have been found

to actively elicit help from their mothers to achieve a goal (Mosier & Rogoff, 1994).

Caruso (1993) examined the exploratory and problem-solving behaviors in a group o f 11-

to 12-month-old infants. To elicit exploration, the infants were presented with toys that

were novel to the infants but not completely unfamiliar in terms of the infants’ prior

experience o f objects. Exploratory play was coded based on the number o f ways the

infant explored a toy, the infant’s use o f the same exploratory behavior with different

toys, and the use o f an exploratory behavior that had previously been used after using

new behaviors.

Next, problem solving was examined by using tasks specifically designed to elicit

problem solving. First, the infant was presented with a Plexiglas box that contained a

small toy. The box contained two openings, and the toy would only fit through one o f the

openings. Infants were prompted to retrieve the toy from the box. The second task

involved two Plexiglas shields placed parallel to each other and attached to a wooden

base. The shields were close enough together that an infant’s hand would not fit between

9

them. A toy was placed between the two shields with a string attached to the toy and

draped over the top and to the outside of one o f the shields. The child was again

encouraged to retrieve the toy from the apparatus. Problem-solving behaviors were then

coded according to the child’s looking behaviors at both the apparatus and the toy,

behaviors directed toward the apparatus, reaching, touching, successful and unsuccessful

attempts to remove the toy, and absence of behaviors directed at the apparatus.

Information about persistence, strategy use, and sophistication in problem solving were

gathered from the coding. Problem solving was represented by the infant’s persistence in

trying to retrieve the toy, the number of different strategies the infant tried, and whether

the infant solved the problem right away, after some or lots o f trial and error, or not at all.

The infant’s breadth and depth o f exploratory play was then compared to the problem

solving variables to determine if relationships existed between the two types of play. The

major finding was that as early as one year o f infancy the child’s breadth o f exploratory

behaviors, or the number o f different schemes used to explore an object, were related to

the child’s problem-solving behaviors.

DeLoache, Sugarman, and Brown (1985) studied the corrections 18- to 42-month-

old children made to errors that occurred while trying to nest a set of seriated cups. The

cups were placed in front of the child and the child was told that the cups were for him or

her to play with. If after two minutes the child did not spontaneously try to nest the cups,

the experimenter fully nested the cups out of the child’s sight and then presented them to

the child. After the child could see the end result, the experimenter again took the cups

out of the child’s sight, disassembled them, and placed them back on the table. Findings

10

indicated that the children’s error correction strategies became more flexible with age,

meaning the younger children tended to focus on the fact that two o f the cups did not fit

together, while the older children incorporated strategies that involved using all o f the

cups. The authors concluded that more extensive research is needed regarding children’s

problem solving in terms of how children correct errors made while attempting to achieve

a goal.

Children not only develop strategies used to correct errors when attempting to

achieve a goal, but through this experience there seems to be a period in development

when they begin focusing on producing expected outcomes (Bullock & Lutkenhaus,

1988). Bullock and Lutkenhaus observed 15- to 35-month-old children as they

participated in play and clean-up tasks. Tasks involved using blocks to build a tower and

to dress a wooden figure. For the tower-building task, five trials were presented. Each

trial consisted of three blocks, each o f which was painted in such a way that when the

blocks were stacked into a tower they would form a picture. The children were also

presented with unpainted blocks. The experimenters were looking to see if the children

would stop building the tower once the desired outcome was reached or if they would

keep working by using the unpainted blocks. For the figure-dressing task, the children

were presented with a wooden figure that was surrounded by a box. The box contained

four blocks of different colors, and their positions in the box were marked with matching

colors painted on the inside o f the box. The children were told that the blocks were the

figure’s clothes and the figure needed them to stay warm. The children were also

presented with extra blocks not needed to dress the figure. After being asked to dress the

11

figure, the experimenters again looked for whether the children stopped once the desired

outcome was reached. A clean-up task involved cleaning a blackboard with chalk

scribbled on it. The children were shown how to dunk the sponge in a bucket o f water,

wring it out, and use it to clean the chalk off the board. The experimenters looked to see

whether the children would clean with the goal to get the chalk off the chalkboard and not

just move the sponge around haphazardly. Results indicated that the younger children

were more activity-oriented in that they focused on the activity in which they were

engaged rather than the outcome they were expected to produce. The older children

showed more outcome-oriented tendencies in that they stopped playing when the desired

outcome had been reached. The authors concluded that children begin to structure their

activities in relation to a desired or expected outcome around three years o f age. This is

an important finding to consider when gathering information about a preschooler’s

development o f problem-solving skills. According to Bullock and Lutkenhaus, one

would expect that a 4-year-old would attempt to solve problems with outcome-oriented

goals rather than activity-oriented goals.

Research regarding young children’s development of problem-solving skills goes

beyond preschool as well. Results o f Klahr and Robinson’s (1981) study revealed that by

first grade, children have acquired a vast array of problem-solving schemes that can be

applied to novel tasks. The subjects in the study ranged from 3.6 to 6.3 years o f age. A

modified version o f the original Tower of Hanoi task (Simon, as cited in Klahr &

Robinson, 1981) was used. The tasks consisted o f three pegs, one o f which contained a

stack o f disks ranging in size. The tasks varied in goal type. The directions of one task

12

were to move the disks one at a time to a second peg, and at no time could a larger disk

be stacked on top o f a smaller disk. In a simpler version o f the task, the directions were

to make sure all the pegs were occupied by disks. The tasks also varied in difficulty,

ranging from one to seven moves required to complete the task. In order for a young

child to solve this type o f problem, the child must be able to use problem-solving skills

including systematic trial and error and planning. Results indicated that the 6-year-olds

were successful in completing the tasks involving up to six moves, but the 4-year-olds

were successful only in completing the tasks involving up to two moves. This type o f

research demonstrates that the knowledge a school psychologist gathers about a child’s

ability to problem solve will reveal information about that child’s level o f cognitive

functioning. This type o f knowledge is imperative for designing effective interventions

because the intervention must be matched with the child’s ability to succeed with the

intervention.

Facilitation in Play Assessment

One aspect o f play assessments that varies among different types o f assessment is

the level o f facilitation involved in the play session. Specifically, play assessments tend

to differ with regard to the amount o f directions that are given, the toys provided, and the

ways in which behaviors are elicited from the child (Athanasiou, 2000). Facilitation is

sometimes performed, for instance, by an adult experimenter modeling behaviors for the

child (Ungerer, Zelazo, Kearsley, & O’Leary, 1981; Watson & Fischer, 1977; and

Watson & Jackowitz, 1984) and sometimes by the child’s mother participating in play

with the child (Fein & Fryer, 1995).

13

Fein and Fryer (1995) were interested in finding out the effects of parental

facilitation on a child’s level and amount o f pretend play, so they reviewed research that

involved parents in the play assessments o f 12- to 36-month-old children. The authors

found that the mother’s involvement increased the amount of the child’s pretense but that

results were inconclusive regarding the influence of parental involvement on the child’s

level o f sophistication in play. Watson and Jackowitz (1984) examined children’s use o f

spontaneous play by having the experimenter model talking on the phone to children ages

14 to 25 months. Then, immediately prior to leaving the room, the experimenter asked

the children to imitate the behavior while waiting for the examiner to return. Various

agents and objects were used for this task, ranging from least to most difficult in terms o f

symbolic substitutions. For example, the items ranged from the experimenter talking into

a toy telephone to a doll talking to a toy banana to a wooden block talking to a toy car, to

name a few of the steps. The children were then observed for spontaneous symbolic

play. Findings revealed that all children showed some form o f symbolic play after the

modeling occurred. Even on tasks that they performed incorrectly, they still

demonstrated some type of symbolic play. For example, children may have failed a task

in which they were asked to make the doll talk to the toy banana, but they still may have

demonstrated use of symbolic play by talking into the toy banana themselves. Similarly,

Watson and Fischer (1977) examined the effects o f modeling symbolic behaviors to

children aged 14 to 24 months. The experimenters used themselves, a doll, and a wooden

block as agents and sleeping, eating and washing as the pretend activities. These

activities were modeled to the children, and then the experimenter left the children to

14

play freely for several minutes. Findings indicated that the modeling elicited pretend

play in the majority o f the children studied. Ungerer et al. (1981) also used modeling to

examine the effects o f age on symbolic play. They studied children of 18, 22, 26, and 34

months of age. First, the children engaged in free play for several minutes. Next, the

experimenter modeled four different play behaviors before leaving the children to play

freely again. As age increased, children used more imaginative substitution in their play.

All of these studies are examples o f how facilitation has been used to study different

aspects of children’s play.

Whether facilitated or non-facilitated play assessments are better for gaining a

true representation of a child’s skills is not clear. Research regarding play assessment

involving typical children tends to involve non-facilitated play. On the other hand,

research regarding play assessment involving exceptional children often involves

facilitation (e.g., Beeghly, Weiss Perry, & Cicchetti, 1989; Roach, Stevenson, Barratt,

Miller, 8c Leavitt, 1998; Rosenburg, Robinson, & Beckman, 1986; Spencer, 1996; and

Ungerer & Sigman, 1981). Some believe that facilitators provide the child with the

necessary assistance to allow the child to demonstrate a higher level o f skills than he or

she would without facilitation during play (Linder, 1993). Others, however, believe this

is not always the case. For example, Roach et al. (1998) found that the interactions o f

mothers and their children with Down syndrome did not significantly affect the children’s

play behaviors. Some researchers use facilitation only after observing the child during

free play to encouraged the child to play with toys or perform certain tasks not observed

during free play (Linder, 1993; Ryalls et al., 2000).

15

Problem Solving and Facilitation

Whether a child’s play is facilitated or not during a play assessment could have an

impact on the developmental level that is displayed by the child during play. As

discussed earlier, facilitation has been used to study various aspects o f children’s play

(e.g., Fein & Fryer, 1995; Ungerer, Zelazo, Kearsley, & O’Leary, 1981; Watson &

Fischer, 1977; Watson & Jackowitz, 1984). Whether facilitation has an impact on the

degree and amount o f problem-solving a child displays during play, however, has not

been given attention in the play assessment research. Malone, Stoneman, and Langone

(1994) suggested that play behaviors were more reflective of true developmental level in

free-play settings in which the child is allowed to play independently at home rather than

in more structured classroom settings in which the child is allowed to interact with peers.

In the free play sessions, adults were discouraged from interacting with the child as well.

Taking these findings into consideration, perhaps an adult-facilitated play setting would

hinder a child’s demonstration o f higher-order play skills than if the child were left to

play alone with no facilitation (Malone et al., 1994). Hanline (1999), while discussing

the use o f play as a learning tool, stated that in order to be effective in engaging children

in active participation in play for learning purposes, the play setting needs to be carefully

planned. This could also mean for the present study that a structured, facilitated session

would be better for engaging children in problem-solving tasks than a free-play session in

which the children may or may not engage in problem solving. While these ideas may

seem logical, the problem still exists that there is no empirical research to date that

suggests whether or not facilitation is necessary to assess a child’s problem-solving skills.

16

The current study utilized the PACSS method to answer questions about whether or not

facilitation is necessary or beneficial in eliciting problem-solving behaviors in children

during play assessment.

Summary

Information about a child’s problem-solving skills is an integral part of an overall

assessment of the preschool child’s cognitive development. If the level of problem

solving is to be examined as a component of play assessment, the optimal type of play

setting for inviting problem-solving behaviors must be determined. Furthermore, the

child’s skill level in problem solving without facilitation versus the child’s potential skill

level when provided with adult facilitation and prompting must be examined. The

present study examined two types of play sessions, non-facilitated versus structured

facilitated, in an attempt to determine which setting is more conducive to eliciting

problem-solving behaviors using the PACSS method.

The Present Study

The present study used PACSS to evaluate the problem-solving behaviors in

toddlers across two different types o f settings, nonfacilitated and structured facilitated.

Participants engaged in free play sessions and were divided into two groups. In the

nonfacilitated group, the participants were subject to minimal interaction with adults in

the room. In the structured facilitated group, a session facilitator adhered to structured

guidelines with respect to the toys and types o f play toward which the participants were

directed.

17

The purpose o f the present study was to determine whether the level o f problem

solving behaviors would differ in a nonfacilitated play session versus a structured

facilitated play session. No previous research has been conducted in the area of problem

solving with respect to session facilitation, and the need for research in this area has been

expressed (Kelly-Vance et al., 2000). It was expected that the results of the study would

answer the question about whether the level of problem solving behaviors displayed

throughout a play assessment would differ significantly between the two types of

sessions.

Within the structured facilitated sessions, children were asked to play with

specific toys that typically elicit problem-solving behaviors (e.g., nesting cups, blocks,

mechanical toys, and puzzles). The same toys were available to the children in the

nonfacilitated sessions, but only in the structured facilitated sessions was the children’s

attention specifically directed to those toys by an adult facilitator. Even though there is

not empirical research as of yet to link facilitation to problem-solving behaviors in play,

it was hypothesized that a higher level of problem-solving behaviors would be exhibited

during the facilitated sessions than in the nonfacilitated sessions because in the former

condition participants were specifically directed toward toys that have been demonstrated

to elicit problem-solving behaviors.

It was expected that certain types o f toys would elicit more problem-solving

behaviors than others. For example, puzzles (Carlson et al., 1998) and nesting cups

(DeLoache et al., 1985) have been demonstrated to elicit problem-solving behaviors.

Because the participants in the structured facilitated sessions were guided specifically

18

toward these types of toys, it was expected that the participants would engage in a greater

number of problem-solving behaviors in the structured facilitated setting and that those

behaviors would be more complex than in the nonfacilitated play setting.

Method

Participants

A total o f 20 typically developing children (12 boys; mean age: M = 28.00, SD =

9.18 and 8 girls; mean age: M = 27.75, SD = 10.51) participated in the study. The sample

consisted of two groups o f children who were Caucasian and from a middle-class

background as determined by maternal occupation. The groups consisted of a

nonfacilitated group and a structured facilitated group. Each group consisted o f ten 18-

to 48- month-old children. The participants were further divided into the following age

categories to be used as an initial screening for matching purposes: (a) 18-24 months, (b)

24-30 months, (c) 30-36 months, (d) 36-42 months, and (e) 42-48 months. The

participants were matched by gender as well as by standard scores as measured by the

Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (see Table 1). The Vineland scores were used solely

to match participants based on their composite scores and was not used as a comparison

to their PACSS score. The Vineland measures the child’s adaptive behavior skills in the

areas o f Communication, Daily Living Skills, Socialization and Motor Skills (Sparrow,

Balia, & Cicchetti, 1984). A purpose of the Vineland is to provide a norm-referenced

assessment and detailed information about a child’s adaptive skills relative to other

children that child’s age (Harrison & Boan, 2000). In an attempt to control for the wide

range o f developmental abilities that surface in preschool children at varying ages, the

participants in the two groups were matched according to their Vineland composite

scores to within two standard deviations instead of being matched by chronological age.

It is important to study cognitive development in typically developing children so that

those children who have deficits in cognitive development can be easily identified as a

first step to intervention. In particular, a child’s ability to problem solve can reveal

information about the level o f cognitive development that the child has reached.

Participants were recruited through word-of-mouth. The experimenters obtained

referral lists from relatives, friends and neighbors consisting o f the contact information

for people who had children ages 18-48 months. Each parent who participated in the

study was given a referral list and was asked to provide names o f people who might also

* be interested in participating.

Setting

The sessions took place in a playroom that was used for play assessment research

at the University o f Nebraska at Omaha. The room consisted of a variety o f toys that

have been shown to elicit various types o f play. Included in the toy selection, but not

limited to these items, was a kitchen set with dishes and pretend food; dolls and related

toys such as a high chair, stroller, blanket, and bottles; a doctor’s bag and veterinary kit; a

tool bench with plastic tools; mechanical toys such as a pretend gumball machine and

pop-up toy; trucks and cars; a barnyard set; play telephones; and blocks and puzzles,

which tend to elicit problem-solving strategies (Carlson, Taylor, & Levin, 1998). Present

in the playroom during each session was a camera operator, a session facilitator, and a

parent/guardian o f the child.

20

Measures

A portion o f the PACSS coding scheme was used and is presented in Appendix A

(Kelly-Vance et al., 2000). The PACSS coding scheme is intended to operationalize

cognitive development in toddlers in the area o f problem solving. The coding scheme

was selected because of its established use in prior related research (Kelly-Vance et al.,

2000) examining play assessment.

Behaviors sampled by the PACSS coding scheme include those codes listed in the

problem solving and planning subdomain of the coding scheme (see Appendix A). The

overall coding scheme encompasses several aspects o f play including exploratory and

symbolic play as well as several subdomains including problem solving and planning,

categorization, and imitation. The present study is part of a larger study comparing the

overall effects of facilitation on children’s play, which utilizes all o f the core domains o f

the PACSS coding scheme. O f specific interest to the present study was the problem

solving and planning subdomain. Thus, for the present study, the problem solving and

planning subdomain is the only category from the coding scheme that is addressed.

Procedures

An experimenter interviewed one parent o f each of the participants using the

Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales to determine an Adaptive Behavior Composite score

for each participant. The interview was conducted within one week of each session. In

addition, during each session the parent was given a consent form to read, sign and date

and was asked to fill out a demographics questionnaire, a checklist of toys the child had

at home, and a referral list.

21

Nonfacilitated group. In the nonfacilitated group, the children were allowed to

play freely for the entire session with minimal interaction with adults. No specific

guidelines were set with regards to the type o f play in which the child was allowed to

engage or the specific toys with which the child was allowed to play. Present in each

session was a session facilitator, whose main role was to answer parent questions; a

camera operator; and a parent/caregiver. Adults were instructed not to guide the child’s

play. General statements that adults were allowed to communicate to the child during the

nonfacilitated sessions were posted on the wall. These statements consisted mostly o f

one- to two-word phrases (e.g., “wow!”, “good job”) and instructions (e.g., “smile”, “y ° u

can imitate”) and are not thought to facilitate play behaviors in the child.

Structured facilitated group. In the structured facilitated group, the conditions

were the same as for the nonfacilitated group except that the facilitator initiated play with

the participants by following a structured set o f guidelines (Appendix B). The facilitator

made a maximum of two attempts at facilitating the child toward a particular activity or

toy. If the child did not demonstrate interest after the two attempts, the facilitator moved

on to another activity or toy from the list of guidelines.

Coding. Each play session was videotaped and lasted a minimum o f 30 minutes.

Videotapes were then observed and problem-solving behaviors were coded by a PACSS

team member. The codes are hierarchical from the least to the highest level of problem

solving. The highest code observed during 30 minutes of play was recorded for each

child.

22

Interrater Reliability. Interrater reliability was established through extensive

training and was maintained at a level o f .90 or greater by calculating the reliability

between two independent observers for all o f the play sessions coded. To become

proficient in using the PACSS coding scheme, the experimenters were trained by coding

videotaped play sessions obtained from a separate play assessment study. Codes were

assigned for every 30-second interval o f play, and a group o f play assessment team

members discussed the codes and any discrepancies among the team members until

overall reliability o f .90 was established for the group. In the current study sessions were

coded simultaneously by two observers. One of the observers took descriptive notes of

the session, including the amount of time spent in certain types of play. At the same

time, a second observer took informal notes about the child’s activities. At the end of

each session, the observers separately recorded the highest level o f play from the core

subdomains as well as the highest level o f problem solving observed during the 30-

minute session, and the two observers checked for agreement. Overall reliability is

determined by dividing the total number of agreements by the total number o f agreements

plus disagreements, then obtaining a percentage. Interrater reliability was maintained at a

level o f 100% both overall and specifically for problem solving.

Data Analyses. Two analyses were conducted. A quantitative analysis consisted

o f obtaining codes for each play session from the Problem Solving and Planning

subdomain. From these codes, the highest level o f problem solving behavior displayed in

each 30- minute session was determined. O f specific interest were the highest level o f

problem solving and the types of toys that elicited the problem-solving behaviors. For

23

the first analysis, the independent variable was the type of session (nonfacilitated versus

structured facilitated). The dependent variable was the level o f problem-solving

behaviors. A one-way analysis o f variance was conducted to compare the highest level

of problem solving in the facilitated group with the highest level o f problem solving in

the nonfacilitated group. The second analysis was qualitative in nature and provides

descriptive data regarding toy type.

Results and Discussion

The highest level of problem solving was coded for each 30-minute play session.

On average, the highest level o f problem solving for the facilitated group (M = 9.20, SD

= 1.87) was comparable to that of the nonfacilitated group (M = 9.00, SD = 0.94), and a

one-way analysis of variance confirmed that the differences were nonsignificant, F(l,18)

= 0.09.

The second analysis was qualitative in nature and provides descriptive data

regarding toys that elicited problem-solving behaviors. Participants in the facilitated

group were specifically directed toward, but not restricted to, the toys and activities listed

in Appendix B. Of those toys, problem-solving behaviors as defined by the PACSS

scheme were elicited by puzzles, a gumball machine, a Disney pop-up toy, nesting cups,

shape sorters, blocks, and Velcro food from the kitchen area. The only toy included in

the facilitated guidelines that did not appear to elicit problem-solving behaviors in either

session type was the bucket of bears. Further, of the toys used to facilitate the

participants in the facilitated group, all o f those that elicited problem solving in the

facilitated group also elicited problem solving in the nonfacilitated group except for the

24

blocks. This does not mean that children did not play with the blocks; however, it simply

means that they did not problem solve or plan with the blocks. Other toys in the

playroom that elicited problem-solving behaviors for both groups included a pop-up toy,

a vase of plastic flowers, a train set, a tool set, and baby bottles. Most o f the problem

solving behaviors included either systematic or nonsystematic trial-and-error problem

solving with these toys, although the children who placed the flowers in a vase received

higher-level codes for being able to put objects into small openings. In addition, the pop

up toy and the gumball machine elicited higher codes than trial-and-error problem

solving for the children who were able to successfully operate the toys on the first try.

Children would often turn puzzle pieces and try them in different positions until the

pieces fit. The train track easily came apart, and children would try putting different

pieces of the track together to reassemble it.

It was expected that a higher level of problem-solving behaviors would be seen

during the facilitated sessions than the nonfacilitated sessions because of the facilitator’s

direction toward specific toys that were believed to elicit problem solving. However, this

was not the case. Participants tended to play with the toys in which they were interested.

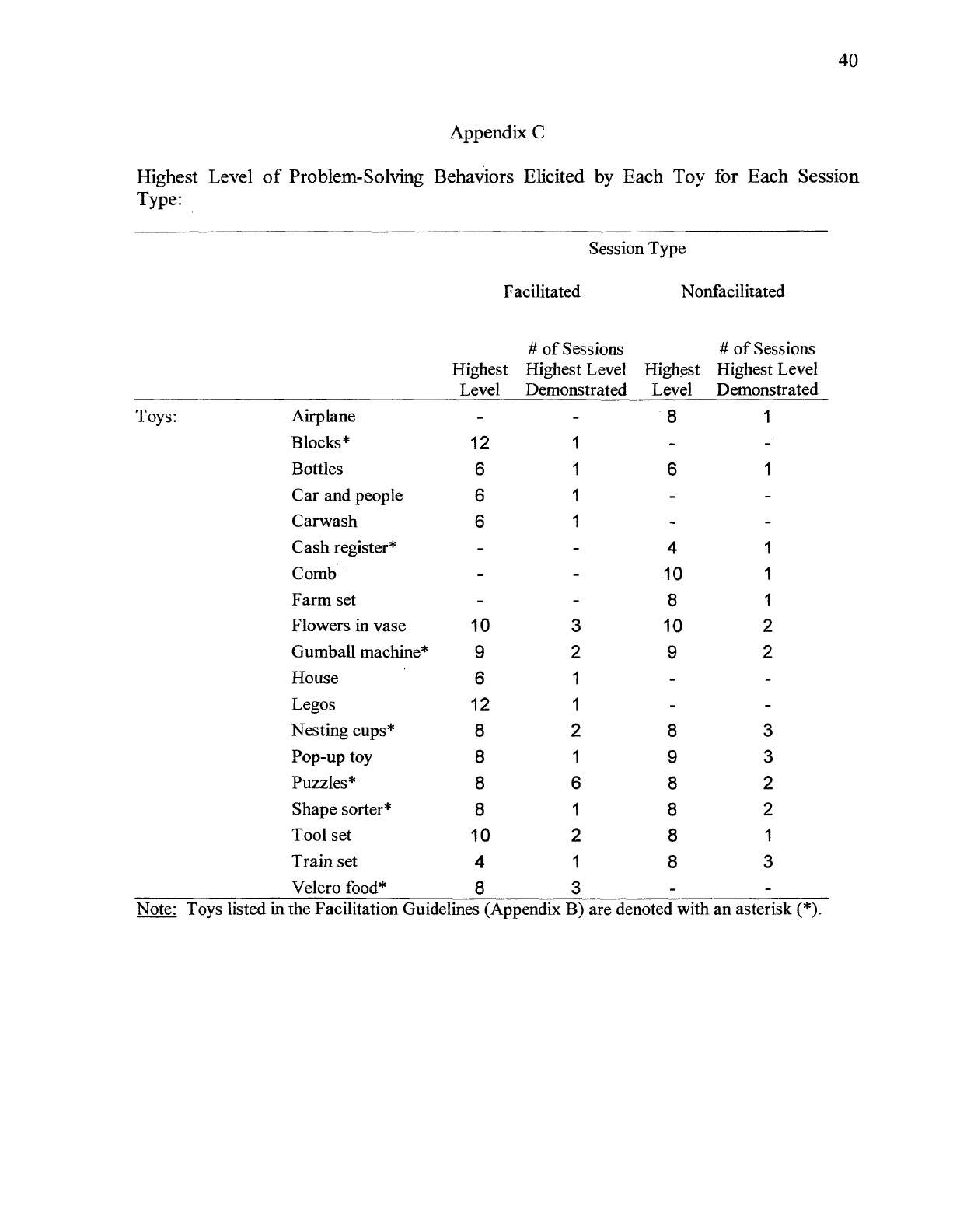

Appendix C illustrates which toys elicited the highest levels o f problem-solving

behaviors within each session type. There are some differences, as would be expected

due to individual differences within each group, but overall the two groups did not differ

greatly in their selection o f toys. One interesting observation is that puzzles elicited the

most instances of problem solving o f any o f the toys, and the majority o f these instances

occurred in the facilitated group.

25

The question of whether facilitation has an impact on the degree o f problem

solving a child displays during play has not previously been given attention in the play

assessment research. In the current study, free play sessions involved adults who were

discouraged from interacting with the child to the extent that the child’s play would be

guided or facilitated. Malone, Stoneman, and Langone (1994) suggested that play

behaviors are more reflective of true developmental level in free-play settings in which

the child is allowed to play independently at home rather than in more structured

classroom settings in which the child is allowed to interact with peers. Although these

authors were not referring to play assessment, their findings still apply. According to

those findings, it would be expected that structured facilitated sessions would hinder a

child’s problem-solving behaviors. This was not necessarily the case because problem

solving behaviors did not differ between the two types o f settings. According to these

results, facilitation did not help nor hinder problem solving.

In contrast to the views of Malone et al. (1994), Hanline (1999) stated that in

order to effectively engage children in active participation in play for learning purposes,

the play setting needs to be carefully planned. Again, the author was. not referring

specifically to play assessment as it was used in the current study; however, the idea that

play needs to be structured in order to engage children to participate applies directly to

the reasoning behind examining facilitation in play assessment as part o f the current

study. However, the play assessment used in the current study was not set up for the

child’s learning purposes, and the type of facilitation used in the facilitated sessions

might not coincide with what Hanline (1999) would consider “carefully planned”. To

26

date there is no empirical research that suggests whether or not facilitation is necessary to

assess a child’s problem-solving skills in the form of play assessment. Results of the

present study provided a foundation for future research to answer this question; in this

study, problem solving was not significantly affected by session type.

Limitations and Considerations for Future Research

Results revealed that problem-solving behaviors exhibited during play

assessments did not differ significantly with respect to session type when the sessions

examined were purely non-facilitated versus structured facilitated. Toys that elicited

problem solving also did not differ greatly between the two types o f sessions (see

Appendix C).

A possible limitation o f the study is that because o f the small sample size,

generalizability o f the findings is limited. It was decided that a small sample would be

selected due to the exploratory nature o f the study. A wider range of problem-solving

behaviors might be found in a larger sample size. Future research should include larger

samples.

Another possible limitation concerns the internal validity of the study. It is

possible that the two types o f play sessions being compared did not differ enough to be

certain that any differences found in problem-solving behaviors can be attributed to the

type o f play session. In fact, since no significant differences were found, it is possible

that the construct o f problem solving was not sufficiently tapped in either session type.

Future research should include comparisons between several different types of play

sessions.

27

A third possible limitation concerns the number of opportunities available for

problem solving in each session. Perhaps future research could include longer play

sessions, allowing more time for children to engage in problem-solving behaviors.

Future research should also address situations in which specific problem-solving tasks

have been set up and requests made o f the child to problem solve. For example, one o f

the toys included in the present study was a train set. Although unintended by the

examiners, the train as well as the train track easily came apart while being played with.

As a result, children who wanted to continue playing with the train set were forced to

problem solve to put the set back together. This illustrates one type o f task that could be

included to facilitate problem solving. Other ideas should be explored in future research.

Problem solving is sometimes difficult to define in terms of a child’s behaviors

and whether or not the child’s actions actually constitute problem solving or some other

type o f cognition. For example, a child’s temperament could have more to do with his or

her apparent ability to solve a problem than actual cognitive ability. The child could have

the cognitive skills available to solve a challenging problem but perhaps a low tolerance

for frustration or a tendency to give up easily, which could limit his or her success in

solving the problem. Due to the subjective nature o f the phenomenon, finding objective

means of ranking problem-solving behaviors from least to most sophisticated is difficult.

More research in the area o f problem solving is vital in this aspect. Without a great deal

o f empirical evidence regarding problem solving and play assessment, researchers and

practitioners should interpret a child’s level o f problem solving with caution when using

a hierarchical coding system for problem-solving behaviors.

28

Some observations were made throughout the process of collecting data for the

present study regarding the PACSS coding scheme (see Appendix A) and some ways in

which it might be revised to diminish the amount of subjectivity in some of the codes.

For example, the first three levels o f problem solving were never used in the current

study and should be given careful consideration, if not completely omitted, in future

research. The code “Searches for an object after seeing it disappear” would not be

appropriate in an assessment unless the assessment protocol called for the facilitator to

purposefully hide an object. The code “Repeats behavior in order to repeat an initially

accidental consequence” is highly subjective because o f the difficulty in determining

whether a consequence was accidental. Likewise, the code “Performs a behavior in order

to produce an anticipated result” is highly subjective due to the difficulty in determining

if the child was anticipating a result.

Another consideration is that the use o f the term “achieve goal” in two of the

codes in the hierarchy should be more clearly defined, again due to its subjectivity.

Unless a child specifically states his or her intentions, it is often difficult to determine the

reasons for the child’s behaviors. If a child achieves an obvious goal, then the problem

solving behaviors will probably be easily noticed; however, if the child does not achieve

a goal and that goal was not obvious to the coders, the child’s attempts at achieving that

goal could easily go unrecognized as problem solving.

Some o f the codes in the hierarchy are not especially subjective, but whether they

represent true problem-solving ability and are truly hierarchical should be further

explored. For example, a child who “Successfully operates a mechanical toy on the first

29

attempt and attempts thereafter” would receive a higher level o f problem solving than a

child who does not successfully operate the toy on the first attempt but uses systematic

trial-and-error problem solving in an attempt to operate the toy. The child who tries

several different methods until he or she successfully operates the toy is clearly problem

solving, but the child who is able to operate the toy on the first try has not solved a ,

problem. Likewise, putting small objects into small openings probably requires good fine

motor skills, but if a child is able to put a small object into a small opening with no

problem, it seems unlikely that the child is exhibiting problem-solving behaviors. Most

likely, the child has problem solved in the past in order to be able to put small objects

into small openings, but once the skill is mastered, the problem no longer exists.

It could be that the codes are measuring too narrow o f a construct. For example, a

child who exhibits nonsystematic trial-and-error problem solving simply gets a lower-

level code than a child who exhibits systematic trial-and-error problem solving.

However, the child who exhibits systematic trial-and-error problem-solving might give

up a lot easier and never solve the problem, while the nonsystematic trial-and-error

problem solver might demonstrate persistence in trying to solve the problem. A child

who knows how to problem solve but lacks persistency might not function as well as a

child who has less-developed problem-solving skills but is persistent when faced with a

problem. Hupp and Abbeduto (1991) studied persistence in young children with

developmental delays. They hypothesized that children who demonstrate persistence in

solving a particular problem are also demonstrating motivation to achieve a goal. The

authors found that persistence was a reflection o f mastery motivation and posited that

30

children’s mastery behavior, or persistence, is important in helping them to learn about

their environment. Likewise, the child who “Uses an adult to achieve a goal” receives a

much lower code than the child who exhibits nonsystematic trial-and-error problem

solving, but what about the child who first uses nonsystematic trial-and-error and, upon

failure to solve the problem, asks an adult for help? It seems that this child is capable of

trying more than one approach to solve the problem, but he or she only receives credit for

nonsystematic trial-and-error problem solving.

Finally, a code that was rarely used in this study was “Uses blocks to build

complex structure [of nine or more pieces]”. Again, it is difficult to determine exactly

what constitutes problem solving with this code. The subdomain includes planning as

well as problem solving, and a child who builds a complex structure has probably used

some planning skills; however, this seems difficult to determine objectively. A child

could easily use nine blocks to build a structure that was not planned. Again, the

question arises as to whether this constitutes problem solving in the same sense as the

other codes in the hierarchy. For example, a child who completes a complex, non-inset

puzzle using systematic trial-and-error problem solving would receive a lower level code

than a child who puts nine blocks together to make a wall.

The hierarchical nature o f the codes in the problem-solving and planning

subdomain was not supported by the current study, as is evident by the previously

mentioned limitations involving the problem-solving codes. This is not surprising

considering that the coding scheme, as developed by Linder (1993), has little empirical

support for its hierarchy. The codes were established from one study, which was limited

31

in sample size and heterogeneity o f participants. In fact, the participants used in the

study had hearing impairments, which limits the generalizability o f the coding scheme to

other populations. If hierarchical codes are going to be used when assessing problem

solving skills in play assessments, further research is needed to determine a more

concrete hierarchy o f problem-solving skills. Practitioners and researchers should also

consider whether a code level is even necessary. A detailed description o f the child’s

problem-solving behaviors and strategies may be more valuable in evaluating a child’s

skills and designing interventions than a standard score. Further, practitioners and

researchers must consider the generalizability of the problem-solving skills elicited

during play assessment to the types o f problems encountered in everyday life and in the

classroom. Although the coding scheme did not prove to be an objective measure of

complexity in problem-solving skills, a hierarchical measure o f problem solving may not

be necessary in play assessment.

Summary

The purpose of the present study was to gain information about whether problem

solving skills would be better assessed in a structured facilitated play session or in a

nonfacilitated play session. Research in the area o f problem solving and play assessment

is scarce, yet play assessment in general is gaining popularity in the field of early

childhood assessment. Although the sample size was small and homogeneous with

regard to ethnicity and socioeconomic status, results indicate that facilitation did not

significantly affect the level of problem solving exhibited by the participants. As play

assessment becomes more widely used, it is important for practitioners to know what type

32

o f play assessment will yield results that are the most reflective o f the child’s abilities and

skills.

/

33

References

Athanasiou, M. S. (2000). Play-based approaches to preschool assessment. In Bracken, B.

A. (Eds.), The psychoeducational assessment o f preschool children, (pp. 412-

427). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Beeghly, M., Weiss Perry, B., & Cicchetti, D. (1989). Structural and affective dimensions

of play development in young children with Down syndrome. International

Journal o f Behavioral Development, 12, 257-277.

Bullock, M., & Lutkenhaus, P. (1988). The development of volitional behavior in the

toddler years. Child Development, 59, 664-674.

Carlson, S. M., Taylor, M., & Levin, G. R. (1998). The influences o f culture on pretend

play: The case o f Mennonite children. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 44, 538-565.

Caruso, D. A. (1993). Dimensions of quality in infants’ exploratory behavior:

Relationships to problem-solving ability. Infant Behavior and Development, 16,

441-454.

Chen, Z., Sanchez, R. P., & Campbell, T. (1997). From beyond to within their grasp: The

rudiments o f analogical problem solving in 10- and 13-month-olds.

Developmental Psychology, 33(5), 790-801.

DeLoache, J. S., Sugarman, S., & Brown, A. L. (1985). The development of error

correction strategies in young children’s manipulative play. Child Development,

56, 928-939.

Elliot, C. D. (1990). Differential Ability Scales: Introductory and technical handbook.

San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

34

Farmer-Dougan, V., & Kaszuba, T. (1999). Reliability and validity o f play-based

observations: Relationship between the play behaviour observation system and

standardized measures o f cognitive and social skills. Educational Psychology,

19(4), 429-442.

Fein, G. 8c Fryer, M. (1995). Maternal contributions to early symbolic play competence.

Developmental Review, 15, 367-381.

Hanline, M. F. (1999). Developing a preschool play-based curriculum. International

Journal o f Disability, Development and Education, 46(3), 289-305.

Harrison, P. L., & Boan, C. H. (2000). Assessment o f adaptive behavior. In Bracken, B.

A. (Eds.), The psychoeducational assessment o f preschool children, (pp. 124-

144). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Hupp, S. C., & Abbeduto, L. (1991). Persistence as an indicator o f mastery motivation in

young children with cognitive delays. Journal o f Early Intervention, 15(3), 219-

225.

James, J. C., & Tanner, C. K. (1993). Standardized testing o f young children. Journal o f

Research and Development in Education, 26(3), 143-152.

Kelly-Vance, L., Gill, K., Schoneboom, N., Chemey, I., Ryan, C., Cunningham, J., &

Ryalls, B. (March, 2000). Coding play assessment: Issues, challenges, and

recommendations. Poster presented at the annual meeting o f the National

Association o f School Psychologists. New Orleans, LA.

Kelly-Vance, L., Needelman, H., Troia, K., & Ryalls, B. O. (1999). Early childhood

assessment: A comparison o f the Bayley Scales o f Infant Development and play

35

assessment in two-year-old at-risk children. Developmental Disabilities Bulletin,

27(1), 1-15.

Klahr, D., Sc Robinson, M. (1981). Formal assessment o f problem-solving and planning

processes in preschool children. Cognitive Psychology, 13, 113-148.

Lidz, C. S. (1977). Issues in the psychological assessment o f preschool children. Journal

o f School Psychology, 15(2), 129-135.

Linder, T. W. (1993). Transdisciplinary play assessment. (2nd ed.) Baltimore: Paul H.

Brookes.

Lowenthal, B. (1997). Useful early childhood assessment: Play-based, interviews and

multiple intelligences. Early Child Development and Care, 129, 43-49.

Malone, D. M., Sc Langone, F. (1999). Teaching object-related play skills to preschool

children with developmental concerns. International Journal o f Disability,

Development and Education, 46(3), 325-336.

Malone, D. M., Stoneman, Z., Sc Langone, J. (1994). Contextual variation of

correspondences among measures of play and developmental level of preschool

children. Journal o f Early Intervention, 18(2), 199-215.

Mosier, C., Sc Rogoff, B. (1994). Infants’ instrumental use o f their mothers to achieve

their goals. Child Development, 65, 70-79.

Myers, C. L., McBride, S. L., Sc Peterson, C. A. (1996). Transdisciplinary, play

assessment in early childhood special education: An examination o f social

validity.

Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 16,

102-126.

36

Neisworth, J. T., & Bagnato, S. J. (1992). The case against intelligence testing in early

intervention. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 12(1), 1-20.

Piaget, J. (1962). Play, dreams, and imitation in childhood. New York: Norton.

Rettig, M. (1998). Environmental influences on the play o f young children with

disabilities. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental

Disabilities, 33,189-194.

Roach, M. A., Stevenson Barratt, M., Miller, J. F., & Leavitt, L. A. (1998). The structure

o f mother-child play: Young children with Down syndrome and typically

developing children. Developmental Psychology, 34, 77-87.

Rosenburg, S. A., Robinson, C. C., & Beckman, P. J. (1986). Measures o f parent-infant

interaction: An overview. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 6, 32-43.

Ross, R. P. (2002). Best practices in the use o f play for assessment and intervention with

young children. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes (Eds.). Best Practices in School

Psychology IV, Volume 2.

Ryalls, B., Gill, K., Ruane, A., Chemey, I., Schoneboom, N., Cunningham, J., and Ryan,

C. (2000). Conducting valid and reliable play-based assessments. Poster

presented at the annual meeting of the National Association o f School

Psychologists. New Orleans, LA.

Salvia, J., & Ysseldyke, J. E. (2001). Assessment o f students. In P. Coryell (Ed.),

Assessment (pp. 4-22). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Schakel, J. A. (1986). Cognitive assessment o f preschool children. School Psychology

Review,15(2), 200-215.

37

Sparrow, S. S., Balia, D. A., & Cicchetti, D. V. (1984). Vineland Adaptive Behavior

Scales. Circle Pines: American Guidance Service.

Spencer, P. E. (1996). The association between language and symbolic play at two years:

Evidence from deaf toddlers. Child Development, 67, 867-876.

Thorndike, R. M., Hagen, E. P., & Sattler, J. M. (1986). Stanford-Binet Intelligence

Scale, Fourth Edition. Chicago: Riverside.

Ungerer, J. A. & Sigman, M. (1981). Symbolic play and language comprehension in

autistic children. American Academy o f Child Psychiatry, 20, 318-337.

Ungerer, J. A., Zelazo, P. R., Kearsley, R. B., & O’Leary, K. (1981). Developmental

changes in the representation o f objects in symbolic play from 18 to 34 months of

age. Child Development, 52, 186-195.

Watson, M. W. & Fischer, K. W. (1977). A developmental sequence of agent use in late

infancy. Child Development, 48, 828-836.

Watson, M. W. & Jackowitz, E. R. (1984). Agents and recipient objects in the

development o f early symbolic play. Child Development, 55, 1091-1097.

Wechsler, D. (1989). Manual fo r the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale o f

Intelligence—Revised. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1966). Play and its role in the mental development o f the child. Soviet

Psychology, 12(6), 62-76.

38

Appendix A

Problem-Solving Skills and Planning

1. Searches for an object after seeing it disappear

2. Repeats behavior in order to repeat an initially accidental consequence

3. Performs a behavior in order to produce an anticipated result

4. Attempts to use an adult to achieve a goal (with or without success)

5. Makes a single attempt to activate mechanical toy or achieve goal,

unsuccessfully

6. Uses nonsystematic trial-and-error problem-solving without systematically

changing behavior

7. Uses an object or toy to obtain an object

8. Uses systematic trial-and-error problem-solving (e.g., alters behavior in an

attempt to solve problems)

9. Successfully operates a mechanical toy on first attempt and attempts thereafter

(e.g., gumball machine, Disney pop-up toy)

10. Puts small objects into little openings (the size o f a golf ball or smaller)

11. Solves problems by logically relating one experience to another (child states

that present situation is like a previously experienced situation)

12. Uses blocks to build complex structure (minimum o f nine pieces or a structure

that can easily be identified)

39

Appendix B

Facilitation Guidelines

• Encourage the child to play with the specific toys contained in the following toy list by

saying, “Here, let's play with these. ”

• If they do not play with the toys, say,

“What can you do with this toy? ”

Toy List

Nesting cups

Bears

Blocks

Puzzles

Shape sorter

Gumball machine or Cash register (child must play with one)

Drawing

• When you are playing with the bears and/or blocks, give the following specific

commands:

“Hand me th e

_________________

one. ”

Big

Little

Tall

Short

Tallest

Shortest

First, middle, last (you will have to line up 3 bears)

• Go to the kitchen area and say:

“L e t’s make dinner. ”

• During this time you may say:

“What are you doing? ” and “What else can you do? ”

40

Appendix C

Highest Level of Problem-Solving Behaviors Elicited by Each Toy for Each Session

Type:

Session Type

Facilitated Nonfacilitated

Highest

Level

# of Sessions

Highest Level

Demonstrated

Highest

Level

# of Sessions

Highest Level

Demonstrated

Toys: Airplane

- -

8

1

Blocks*

12

1 -

-

Bottles

6

1

6

1

Car and people

6

1

-

-

Carwash

6

1 -

-

Cash register*

-

-

4 1

Comb

-

-

10

1

Farm set

- -

8

1

Flowers in vase

10 3

10

2

Gumball machine*

9 2

9

2

House

6

1

-

-

Legos

12 1

-

-

Nesting cups*

8

2

8

3