Digital India

Technology to transform

a connected nation

March 2019

Digital

India

McKinsey Global Institute

Since its founding in 1990, the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) has sought to develop a

deeper understanding of the evolving global economy. As the business and economics

research arm of McKinsey & Company, MGI aims to provide leaders in the commercial,

public, and social sectors with the facts and insights on which to base management

and policy decisions.

MGI research combines the disciplines of economics and management, employing the

analytical tools of economics with the insights of business leaders. Our “micro-to-macro”

methodology examines microeconomic industry trends to better understand the broad

macroeconomic forces affecting business strategy and public policy. MGI’s in-depth reports

have covered more than 20 countries and 30 industries. Current research focuses on six

themes: productivity and growth, natural resources, labour markets, the evolution of global

financial markets, the economic impact of technology and innovation, and urbanisation.

Recent reports have assessed the digital economy, the impact of AI and automation on

employment, income inequality, the productivity puzzle, the economic benefits of tackling

gender inequality, a new era of global competition, Chinese innovation, and digital and

financial globalisation.

MGI is led by three McKinsey & Company senior partners: Jacques Bughin, Jonathan Woetzel,

and James Manyika, who also serves as the chairman of MGI. Michael Chui, Susan Lund, Anu

Madgavkar, Jan Mischke, Sree Ramaswamy, and Jaana Remes are MGI partners, and Mekala

Krishnan and Jeongmin Seong are MGI senior fellows.

Project teams are led by the MGI partners and a group of senior fellows and include

consultants from McKinsey offices around the world. These teams draw on McKinsey’s global

network of partners and industry and management experts. The MGI Council, which includes

leaders from McKinsey offices around the world and the firm’s sector practices, includes

Michael Birshan, Andrés Cadena, Sandrine Devillard, André Dua, Kweilin Ellingrud, Tarek

Elmasry, Katy George, Rajat Gupta, Eric Hazan, Acha Leke, Scott Nyquist, Gary Pinkus, Sven

Smit, Oliver Tonby, and Eckart Windhagen. In addition, leading economists, including Nobel

laureates, advise MGI research.

The partners of McKinsey fund MGI’s research; it is not commissioned by any business,

government, or other institution. For further information about MGI and to download reports,

please visit www.mckinsey.com/mgi.

McKinsey & Company in India

McKinsey & Company is a management consulting firm that helps leading corporations and

organisations make distinctive, lasting, and substantial improvements in their performance.

Over the past eight decades, the firm’s primary objective has remained constant: to serve as

an organisation’s most trusted external adviser on critical issues facing senior management.

With consultants deployed from more than 128 offices in 65 countries, McKinsey advises

companies on strategic, operational, organisational, and technological issues. The firm has

extensive experience in more than 20 major industry sectors and eight primary functional

practice areas as well as in-depth expertise in high-priority areas for today’s business

leaders. Across India, McKinsey & Company serves clients in the public and private sectors

from offices in Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, and Bangalore. For more information on McKinsey

in India, please see www.mckinsey.com/Global_Locations/Asia/India.

Copyright © McKinsey & Company 2019

Digital India:

Technology

to transform a

connected nation

Authors

Noshir Kaka, Mumbai

Anu Madgavkar, Mumbai

Alok Kshirsagar, Mumbai

Rajat Gupta, Mumbai

James Manyika, San Francisco

Kushe Bahl, Mumbai

Shishir Gupta, Delhi

Preface

India is establishing itself as a major presence in the digital economy. By any number of key

metrics, from internet connections to app downloads, both the volume and the growth of

its digital economy now exceed those of most other countries. Government and the private

sector are moving rapidly to spread high-speed connectivity across the country and provide

the hardware and services to put Indian consumers and businesses online. What does this

increased connectivity mean in economic terms? And how quickly and effectively will the

country be able to harness digital technologies for the prosperity of all Indians?

This report by the McKinsey Global Institute is the latest research in an ongoing series on the

impact of digital technologies on economies around the world. We build on our existing work

on digital’s potential and challenges in the United States, Europe, and some other economies

to probe how digital forces allow firms to connect, automate, and analyse—capabilities that will

enable them to reshape their value chains and increase productivity. In line with our “microto-

macro” approach, we examine in depth four sectors in India—agriculture, healthcare, retail, and

logistics—that can benefit from taking digitisation to a new level.

This research is a joint venture between McKinsey & Company’s office in India and the McKinsey

Global Institute. It was led by three McKinsey & Company senior partners based in Mumbai—

Noshir Kaka, Alok Kshirsagar, and Rajat Gupta—along with Anu Madgavkar, an MGI partner in

Mumbai, who directed the project. James Manyika, MGI’s chairman, based in San Francisco, and

Kushe Bahl, a McKinsey partner in Mumbai, helped steer the effort. Kanika Gupta and Shishir

Gupta headed the research team, which was composed of Rishi Arora, Archit Maheshwari,

Chandan Kar, Ipshita Mandal, Preksha Mangal, Ketav Mehta, Ayush Mittal, TJ Radigan, Sailee

Rane, Himanshu Satija, Tanya Sharma, Maheep Singh, Shantanu Sinha, and Shivika Syal.

This project greatly benefited from a year-long research collaboration between McKinsey &

Company and the Government of India’s Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology

(MeitY) that culminated in the government’s report “India’s Trillion Dollar Digital Opportunity,”

released in February, 2019. We are especially grateful to Ravi Shankar Prasad, Honorable

Minister of Law and Justice and Electronics and Information Technology, Government of India,

Nandan Nilekani, co-founder and chairman of Infosys and former chairman of the Unique

Identification Authority of India, and Ajay Sawhney, union secretary, MeitY, for their guidance

and thought partnership.

We received many valuable insights through this research collaboration from Government of

India officials including Amitabh Kant, CEO of NITI Aayog; Dr. Rajiv Kumar, vice chairman of NITI

Aayog; and Aruna Sundararajan, union telecom secretary, Department of Telecommunication.

We are especially indebted to officials of MeitY and representatives of several other ministries

and departments, among them Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare; Commerce and Industry

(Government e Marketplace); Finance (DBT Mission); Health and Family Welfare; Higher

Education; Labour and Employment; Power; School Education and Literacy; and Skill

Development and Entrepreneurship.

We are grateful to business and industry leaders who interacted with us along with their teams

to provide input to our research: Bhavish Aggarwal, co-founder and CEO of Ola; Mukesh

Ambani, chairman and managing director of Reliance India Limited; Rajan Anandan, CEO of

Google India; N. Chandrasekaran, group chairman of Tata Sons; R. Chandrasekhar, former

president of NASSCOM; Deepak Garg, founder and CEO of Rivigo; Debjani Ghosh, president

of NASSCOM; Roopa Kudva, managing director of Omidyar Network India Advisors; Saurabh

Kumar, founder and CEO of Agricx Lab; Anant Maheshwari, president of Microsoft India; Sunita

Nadhamuni, director of technology at Dell EMC; Pradeep Parmeswaran, India head of Uber;

Siddharth Patodia, a co-founder of iGenetic Diagnostics; Kunal Prasad, co-founder and chief

operating officer of CropIn Technology Solutions; Rishad Premji, chairman of NASSCOM;

Aditya Puri, managing director of HDFC Bank; Vijay Shekhar Sharma, founder and CEO of

Paytm; Dr. Devi Shetty, chairman and executive director of Narayana Health; Vikram Shroff,

executive director of UPL; Aditya Singh, managing director of DaVita Care (India); Siddharth

Tata, a co-founder of Purple Chilli; and Naveen Tewari, founder and CEO of InMobi. We also

thank representatives of several other business and industry organisations from whom we

obtained valuable insights, among them ABB, Amazon India, Apollo Hospitals, Axis Bank,

Bharti Enterprises, GE India, Hindustan Petroleum, Hindustan Unilever, ICICI Bank, Indian Oil,

Kotak Mahindra Bank, Larsen & Toubro, Mahindra Group, Piramal Enterprises, Siemens,

State Bank of India, and Vodafone.

Several experts from nonprofits, think tanks, and other institutions challenged our thinking,

and we are grateful to them, especially Dilip Asbe, managing director and CEO of National

Payments Corporation of India; Sanjay Jain, a fellow at the Indian Software Products Industry

Round Table (iSPIRT) and chief innovation officer of the Centre for Innovation Incubation and

Entrepreneurship at the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad; Lalitesh Katragadda,

technologist and architect of AP FiberNet; Nachiket Mor, India country director of the Bill &

Melinda Gates Foundation; Srikanth Nadhamuni, CEO of the eGovernments Foundation; Paresh

Parasnis, CEO of the Piramal Foundation; Samir Saran, president of the Observer Research

Foundation; and Sharad Sharma, governing council member and co-founder of iSPIRT.

Many McKinsey colleagues, based in India and outside, generously shared their time and

provided valuable insights. We are grateful to Chirag Adatia, Salil Aggarwal, Anubhav

Bhattacharjee, Sujit Chakrabarty, Bo Chen, Mahima Chugh, Nicolas Denis, David Fiocco,

K Ganesh, Raghav Gupta, Eric He, Daniel Hui, Kanika Kalra, Joshua Katz, Suyog Kotecha,

Ashok Kumar, Saurabh Kumar, Mehdi Lahrichi, Archana Maganti, Anne Martinez, Neelesh

Mundra, Nitika Nathani, James Naylor, Clayton O’Toole, Sudiptha Pal, RS Mallya Perdur,

Naveen Prashanth, Ankur Puri, Chandrika Rajagopalan, Florian Schaudel, Sameer Shetty,

Kunwar Singh, Shwaitang Singh, Marek Stepniak, Owen Stockdale, Renny Thomas, Jordan

VanLare, Sri Velamoor, Khiloni Westphely, and Hanish Yadav.

We are deeply indebted to our academic adviser, Rakesh Mohan, a senior fellow at the Jackson

Institute for Global Affairs at Yale University, who provided valuable feedback and guidance

throughout the research.

The report was edited and produced by MGI senior editor Mark A. Stein and editorial director

Peter Gumbel, production manager Julie Philpot, graphic design team leader Vineet Thakur,

senior graphic designers Marisa Carder, Pradeep Singh Rawat, and Patrick White, and graphic

artist Margo Shimasaki. Cathy Gui and Rebeca Robboy of MGI’s external communications team

helped disseminate and publicise the report, while Lauren Meling, MGI digital editor, aided with

digital and social media diffusion.

This report contributes to MGI’s mission to help business and policy leaders understand the

forces transforming the global economy, identify strategic locations, and prepare for the

next wave of growth. As with all MGI research, this research is independent and has not been

commissioned or sponsored in any way by any business, government, or other institution.

We welcome your comments at MGI@mckinsey.com.

Jacques Bughin

Director, McKinsey Global Institute

Senior Partner, McKinsey & Company, Brussels

James Manyika

Chairman and Director, McKinsey Global Institute

Senior Partner, McKinsey & Company, San Francisco

Jonathan Woetzel

Director, McKinsey Global Institute

Senior Partner, McKinsey & Company, Shanghai

March 2019

Contents

In brief

Executive summary

1. India’s consumer-led digital leap

2. The digital gap among India’s businesses

3. Potential economic impact of digital applications in 2025

4. Building digital ecosystems

4.1 Agriculture

4.2 Healthcare

4.3 Retail

4.4 Logistics

5. Implications for companies, policy makers, and individuals

Technical appendix

Bibliography

vi

1

23

41

53

69

72

82

94

104

113

121

129

In brief

Digital India:

Technology to transform

a connected nation

India’s digital surge is well under way on the consumer side,

even as its businesses show uneven adoption and a gap

opens between digital leaders and other firms. Thisreport

examines the opportunities for India’s future digital growth

and the challenges that will need to be managed as it

continues to embrace the digital economy.

— India is one of the largest and fastest-growing markets for

digital consumers, with 560million internet subscribers

in 2018, second only to China. Indian mobile data

users consume 8.3 gigabits (GB) of data each month

on average, compared with 5.5 GB for mobile users in

China and somewhere in the range of 8.0 to 8.5 GB in

South Korea, an advanced digital economy. Indians have

1.2billion mobile phone subscriptions and downloaded

more than 12billion apps in 2018. Our analysis of 17

mature and emerging economies finds India is digitising

faster than any other country in the study, save

Indonesia—and there is plenty of room to grow: just over

40percent of

the populace has an internet subscription.

— The public and private sectors are both propelling digital

consumption growth. The government has enrolled more

than 1.2billion Indians in its biometric digital identity

programme, Aadhaar, and brought more than 10million

businesses onto a common digital platform through

a goods and services tax. Competitive offerings by

telecommunications firms have turbocharged internet

subscriptions and data consumption, which quadrupled

in both 2017 and 2018 and helped bridge a digital

divide; India’s lower-income states are growing faster

than higher-income ones in internet infrastructure and

subscriptions. Based on current trends, we estimate

that India will increase the number of internet users by

about 40percent to between 750million and 800million

and double the number of smartphones to between

650million and 700million by 2023.

— Our survey of more than 600 firms shows that digital

adoption among businesses has been uneven across all

sectors. Digital leaders in the top quartile of adopters

are two to three times more likely to use software for

customer relationship management, enterprise resource

planning, or search engine optimisation than firms in the

bottom quartile and are almost 15 times more likely to

centralise digital management. Firm size is not always a

differentiator: while large firms are far ahead in digital areas

requiring large investments like making sales through

their own website, small businesses are leapfrogging

ahead of large ones in other areas, including acceptance

of digital payments and the use of social media and video

conferencing to reach and support customers.

— Digital applications could proliferate across most

sectors of India’s economy. By 2025, core digital sectors

such as IT and business process management, digital

communication services, and electronics manufacturing

could double their GDP level to $355billion to

$435billion. Newly digitising sectors, including

agriculture, education, energy, financial services,

healthcare, logistics, and retail, as well as government

services and labour markets, could each create $10billion

to $150billion of incremental economic value in 2025 as

digital applications in these sectors help raise output,

save costs and time, reduce fraud, and improve matching

of demand and supply.

— The productivity unlocked by the digital economy could

create 60million to 65million jobs by 2025, many of

them requiring functional digital skills, according to our

estimates. Retraining and redeployment will be essential

to help some 40million to 45million workers whose jobs

could be displaced or transformed.

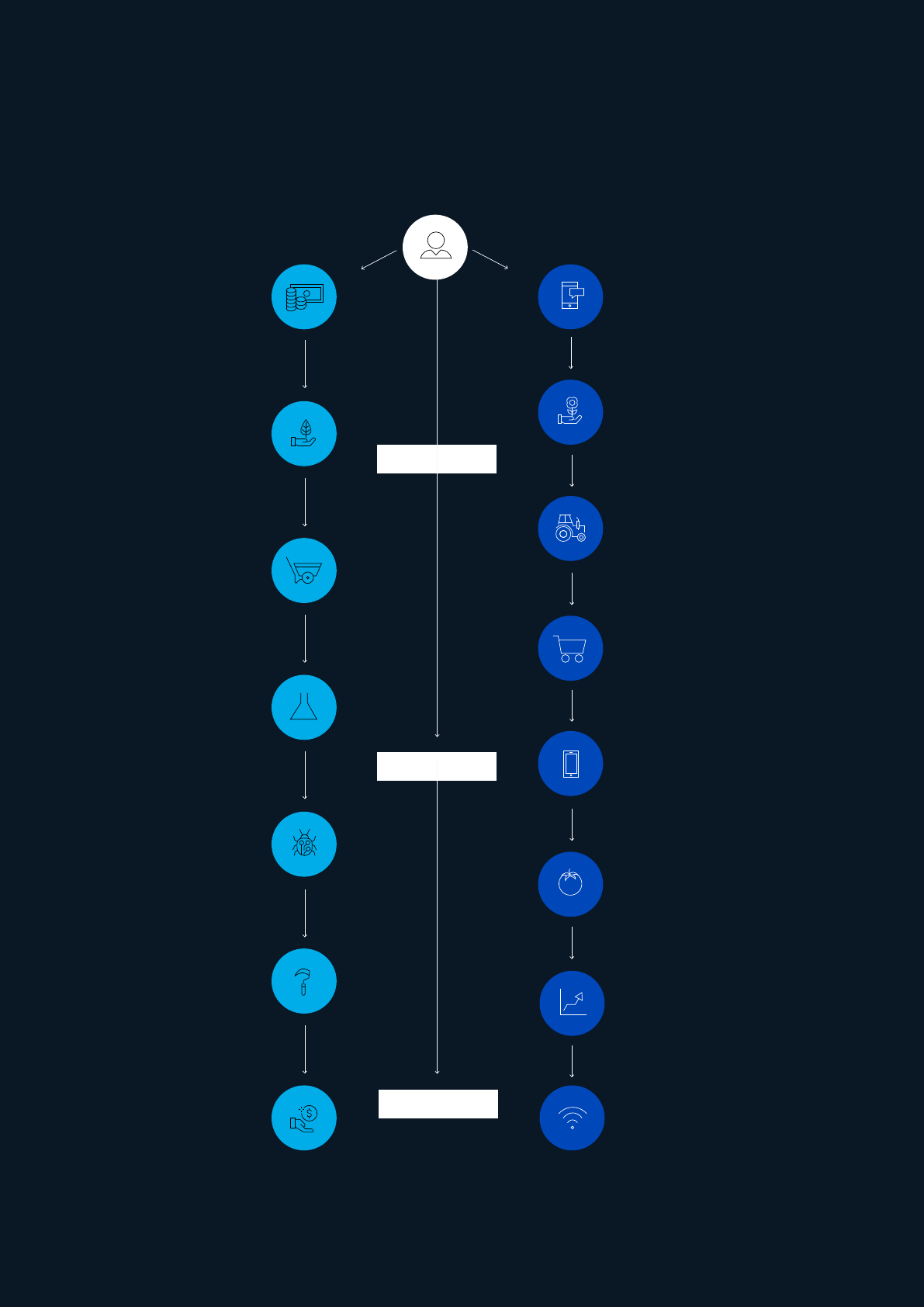

— New digital ecosystems are already visible, reshaping

consumer-producer interactions in agriculture,

healthcare, retail, logistics, and other sectors.

Opportunities span such areas as data-driven lending and

insurance payouts in the farm sector to digital solutions

that map out the most efficient routes and monitor cargo

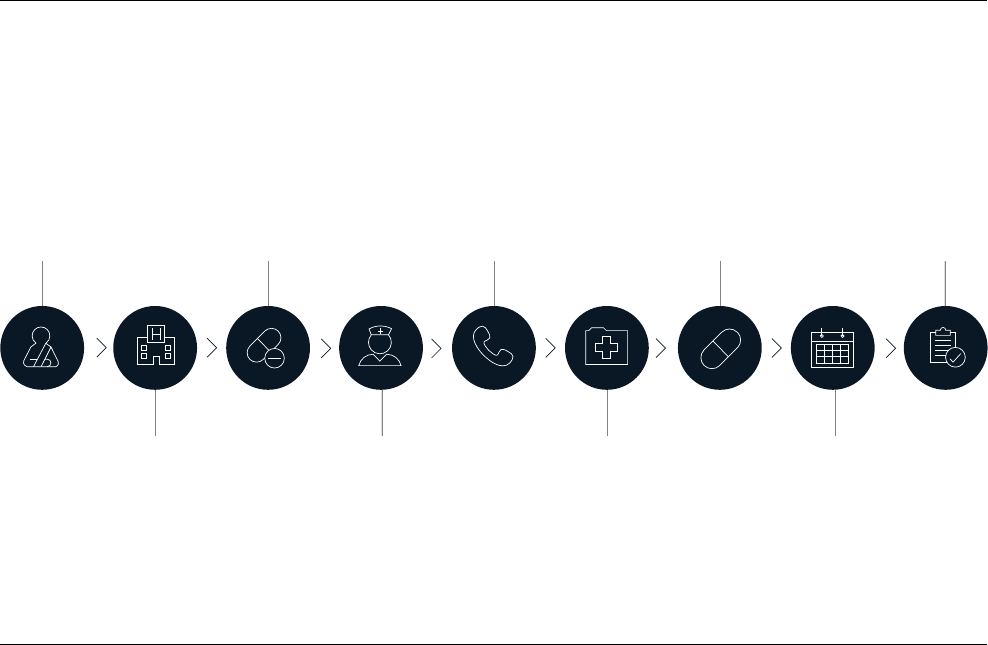

movements on India’s highways. Inhealthcare, patients

could turn to teleconsultations via digital voice or HD

video, and in retail, brick-and-mortar stores would find

value from being part of e-commerce platforms.

— All stakeholders will need to respond effectively if India

is to achieve its digital potential. Executives will need

to anticipate the digital forces that will disrupt their

businesses and invest in building capabilities, including

partnering with universities and outsourcing or acquiring

talent to deliver digital projects. Governments will need

to invest in digital infrastructure and public data that

organisations can leverage even as they put in place

strong privacy and security safeguards. Capturing the

gains of the digital economy will require more ease in

creating, scaling, and exiting startups as well as policies

to facilitate retraining and new-economy jobs for workers.

Individuals will need to inform themselves about how

the digital economy could affect them as workers and

consumers and prepare to capture its opportunities.

The MGI India Firm Digitisation Index shows digitally advanced rms

are pulling ahead of their peers.

Financial

services

70x 30x50x

LogisticsAgriculture

Education

Retail

$ 435bn

Growth potential

Potential value by 2025

(Index top quartile)(Index bottom quartile)

22%

2%

29%

170x

26.2

5.4

560m

239m

18 8,320mb 6.1%

0.1%

2.2

86mb

2014

2018

2014

2018

2014

2018

2014

2018

2014

2018

Digital usage in India is soaring as costs tumble

Unlocking the

potential of technology

Digital India

Number of

smartphones

per 100

people

Total number

of internet

users

Number of

cashless

transactions

per person

Monthly data

consumption

per unique

connection

Monthly data

price (per

1gb as % of

monthly GDP)

Laggards Leaders

13%

46%

3.5x

2.6x

14.5x

Newly digitising sectors will see

signicant value emerge.

Core digital sectors have the potential

to more than double by 2025.

1

Source: McKinsey Global Institute analysis

1

IT business process management, digital communication services, and electronics manufacturing.

Changing core operations to

respond to digital disruption

With centralised digital team Using CRM software

58%

70x

Job and

skills

11.7x

$ 170bn

$ 70bn $ 70bn

$ 50bn

$ 30bn

$ 35bn

Core digital

sectors

$ 170bn

Current value

By 2025, digital could transform India's economy, sector by sector

(Values show upper limit of an estimated range)

The MGI India Firm Digitisation Index shows digitally advanced rms

are pulling ahead of their peers.

Financial

services

70x 30x50x

LogisticsAgriculture

Education

Retail

$ 435bn

Growth potential

Potential value by 2025

(Index top quartile)(Index bottom quartile)

22%

2%

29%

170x

26.2

5.4

560m

239m

18 8,320mb 6.1%

0.1%

2.2

86mb

2014

2018

2014

2018

2014

2018

2014

2018

2014

2018

Digital usage in India is soaring as costs tumble

Unlocking the

potential of technology

Digital India

Number of

smartphones

per 100

people

Total number

of internet

users

Number of

cashless

transactions

per person

Monthly data

consumption

per unique

connection

Monthly data

price (per

1gb as % of

monthly GDP)

Laggards Leaders

13%

46%

3.5x

2.6x

14.5x

Newly digitising sectors will see

signicant value emerge.

Core digital sectors have the potential

to more than double by 2025.

1

Source: McKinsey Global Institute analysis

1

IT business process management, digital communication services, and electronics manufacturing.

Changing core operations to

respond to digital disruption

With centralised digital team Using CRM software

58%

70x

Job and

skills

11.7x

$ 170bn

$ 70bn $ 70bn

$ 50bn

$ 30bn

$ 35bn

Core digital

sectors

$ 170bn

Current value

By 2025, digital could transform India's economy, sector by sector

(Values show upper limit of an estimated range)

Executive summary

With more than half a billion internet subscribers, India is one of the largest and fastest-

growing markets for digital consumers, and the rapid growth has been propelled by public and

private sector alike. India’s lower-income states are bridging the digital divide, and the country

has the potential to be a truly connected nation by 2025. Much more growth is possible. As

India’s digital transformation unfolds, it could create significant economic value for consumers,

businesses, microenterprises, farmers, government, workers, and other stakeholders.

Digital adoption by India’s businesses has so far been uneven, but new digital business

models could proliferate across most sectors. We find that core digital sectors such as IT and

business process management (ITBPM), digital communication services, and electronics

manufacturing could double their GDP level to $355billion to $435billion by 2025, while newly

digitising sectors (including agriculture, education, energy, financial services, healthcare,

logistics, and retail) as well as digital applications in government services and labour markets

could each create $10billion to $150billion of incremental economic value in the same

period. Some 60million to 65million jobs could be created by the productivity surge by 2025,

although redeployment will be essential to help the 40million to 45million workers whose jobs

will likely be displaced or transformed bydigital technologies, based on our estimates.

In India’s new and emerging digital ecosystems of the future—already visible in areas such

as precision agriculture, digital logistics management, and digital healthcare consultations—

business will have to find a new way to engage with customers. All Indian stakeholders

will need to gear up to capture the opportunities and manage the challenges of being a

connected nation.

India’s digital leap is well under way, propelled by both public

and private-sector actions

By many measures, India is on its way to becoming a digitally advanced nation

1

.Just over

40percent of the populace has an internet subscription, but India is already home to one

of the world’s largest and most rapidly growing bases of digital consumers. It is digitising

activities at a faster pace than many mature and emerging economies.

India’s internet user base has grown rapidly in recent years, propelled by the decreasing cost

and increasing availability of smartphones and high-speed connectivity, and is now one of

the largest in the world (Exhibit E1). The country had 560million subscribers in September

2018, second in the world only to China.

2

Digital services are growing in parallel. Indians now

download more apps—12.3billion in 2018—than residents of any other country except China.

3

The average Indian social media user spends 17 hours on the platforms each week, more than

social media users in China and the United States.

4

The share of Indian adults with at least one

digital financial account has more than doubled since 2011, to 80percent, thanks in large part

to the more than 332million people who opened mobile phone–based accounts under the

government’s Jan-Dhan Yojana mass financial-inclusion programme.

5

1

In February 2019, the Indian government released a report highlighting the considerable economic opportunities from

digital technologies and a detailed action plan for realizing them. India’s Trillion Dollar Digital Opportunity, Ministry of

Electronics and Information Technology, Government of India, February 2019.

2

Indian telecom services performance indicator report, June-September 2018, Telecom Regulatory Authority of India.

3

Priori Data, January 2019.

4

We Are Social, Digital in 2018: Southern Asia, January 2018.

5

Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana, November 20, 2018, pmjdy.gov.in/account; Asli Demirgüç-Kunt et al., The Global

Findex Database 2017: Measuring financial inclusion and the fintech revolution, World Bank, April 2018.

1

Digital India: Technology to transform a connected nation

Our analysis of 17 mature and emerging economies across 30 dimensions of digital adoption

since 2014 finds that India is digitising faster than all but one other country in the study,

Indonesia. Our Country Digital Adoption Index covers three elements: digital foundation,

or the cost, speed, and reliability of internet connections; digital reach, or the number of

mobile devices, app downloads, and data consumption; and digital value, the extent to which

consumers engage online by chatting, tweeting, shopping, or streaming. India’s score rose by

90percent between 2014 and 2017, second only to Indonesia’s improvement, at 99percent,

over the same period (Exhibit E2). In absolute terms, India’s score is low, at 32 out of a

maximum 100, comparable to Indonesia’s at 40, but significantly lagging behind the four most-

digitised economies of the 17: South Korea, Sweden, Singapore, and the United Kingdom.

The public sector has been one strong catalyst for India’s rapid digitisation. Thegovernment’s

effort to ramp up Aadhaar, the national biometric digital identity programme, has played a

major role (see Box E1, “Aadhaar, the world’s largest digital ID programme, has enabled many

services”). The Goods and Services Tax Network, established in 2013, brings all transactions

involving about 10.3million indirect taxpaying businesses onto one digital platform, creating

a powerful incentive for businesses to digitisetheir operations.

At the same time, private-sector innovation has helped bring internet-enabled services to

millions of consumers and made online usage more accessible. For example, Reliance Jio’s

strategy of bundling virtually free smartphones with subscriptions to its mobile service has

spurred innovation and competitive pricing across the sector. Overall, data costs have dropped

by more than 95percent since 2013: the cost of one gigabyte fell from 9.8percent of per

capita monthly GDP in 2013 (roughly $12.45) to 0.37percent in 2017 (the equivalent of a few

cents).

6

Average fixed-line download speed quadrupled between 2014 and 2017.

7

As aresult,

monthly mobile data consumption per user is growing at 152percent annually—more than

twice the rates in the United States and China (Exhibit E3).

6

Analysys Mason, January 9, 2019; World Bank, October 27, 2018.

7

Akamai’s state of the internet: Q1 2014 report, Akamai Technologies, May 2014; and Akamai’s state of the internet: Q1 2017

report, Akamai Technologies, March 2017.

95%

Decline in data costs

since 2013

Exhibit E1

India is among the top two countries globally on many key dimensions of digital adoption.

SOURCE: Priori Data, January 2019; Strategy Analytics, 2018; TRAI, September 30, 2018; UIDAI, April 2018; We Are Social, January 2019;

McKinsey Global Institute analysis

Exhibit 1

India no. 1

globally

1.2b

people enrolled in the world’s largest unique digital identity program

India no. 2

globally,

behind China

12.3b

app downloads

in 2018

1.17b

wireless phone

subscribers

560m

internet

subscribers

354m

smartphone

devices

294m

users engaged in

social media

India is among the top two countries globally on many key dimensions of digital adoption

Source: Priori Data, January 2019; Strategy Analytics, 2018; TRAI, September 30, 2018; UIDAI, April 2018; We Are Social, January 2019; McKinsey

Global Institute analysis

Digital India

Report exhibits, VI

mc 0311

ES and report

[mc]

I’ve used Theinhardt Light and

Theinhardt Medium (*not* the

PPT Bold button).

2 Digital India: Technology to transform a connected nation

Exhibit E2

India, coming o a low base, is the second-fastest digital adopter among 17 major

digital economies.

1

MGI’s Country Digital Adoption Index represents the level of adoption of digital applications by individuals, businesses, and governments

across 17 major digital economies. The holistic framework is estimated based on 30 metrics divided between three pillars: digital

foundation (eg, spectrum availability, download speed), digital reach (eg, size of mobile and internet user bases, data consumption

per user), and digital value (eg, utilisation levels of use cases in digital payments or e-commerce). Principal component analysis was

conducted to estimate the relative importance of the three pillars: 0.37 for digital foundation, 0.33 for digital reach and 0.30 for digital

value. Within each pillar, each element is assigned equal value, with indicators normalised into a standard scale of 0100 (0 indicating

lowest possible value). A simple average of the normalised values was then used to calculate the index.

SOURCE: Akamai’s state of the internet: Q1 2014 report; Akamai’s state of the internet: Q1 2017 report; Analysys Mason; Euromonitor

International consumer finance and retailing overviews, 2017 editions; International Telecommunication Union; UN

e-Government Survey; Strategy Analytics; Open Signal; Ovum; We Are Social; Digital Adoption Index, World Bank;

McKinsey Global Institute analysis

Exhibit 2

India, coming o a low base, is the second-fastest digital adopter among 17 major

digital economies

Source: Akamai’s state of the internet: Q1 2014 report; Akamai’s state of the internet: Q1 2017 report; Analysys Mason; Euromonitor International

consumer nance and retailing overviews, 2017 editions; International Telecommunication Union; UN e-Government Survey; Strategy Analytics; Open

S

ignal; Ovum; We Are Social; Digital Adoption Index, World Bank; McKinsey Global Institute analysis

1. MGI’s Country Digital Adoption Index represents the level of adoption of digital applications by individuals, businesses, and governments across

17 major digital economies. The holistic framework is estimated based on 30 metrics divided between three pillars: digital foundation (eg,

spectrum availability, download speed), digital reach (eg, size of mobile and internet user bases, data consumption per user), and digital value (eg,

utilisation levels of use cases

in digital payments or e-commerce). Principal component analysis was conducted to estimate the relative importance of the three pillars: 0.37 for

digital foundation, 0.33 for digital reach and 0.30 for digital value. Within each pillar, each element is assigned equal value, with indicators

normalised into a standard scale of 0–100 (0 indicating lowest possible value). A simple average of the normalised values was then used to

calculate the index.

75

73

67

67

66

66

65

64

64

61

58

57

50

47

40

40

Russia

South Africa

Canada

South Korea

Brazil

United Kingdom

Sweden

Australia

United States

Singapore

Japan

Germany

France

Indonesia

Italy

China

India

32

ES and report

C

ountry Digital Adoption Index

1

S

core (0-100), 2017

Growth in Country Digital Adoption Index

% growth, 2014–17

24

United Kingdom

South Africa

Germany

Indonesia

India

27

Russia

China

Canada

Japan

31

90

Italy

France

South Korea

Brazil

30

36

United States

Sweden

44

Australia

Singapore

99

45

44

43

35

35

30

30

25

25

3Digital India: Technology to transform a connected nation

Global and local digital businesses are creating services tailored to India’s consumers and

unique operating conditions. For example, Alibaba-backed Paytm, India’s largest mobile

payments and commerce platform, has more than 300million registered mobile wallet users

and six million merchants.

8

8

Harichandan Arakali, “Paytm reloaded: It’s no longer just a mobile wallet”, Forbes, March 15, 2018.

Box E1.

Aadhaar, the world’s largest digital ID

programme, has enabled many services

Before the Aadhaar programme rolled out in 2009, most

Indians relied on rudimentary physical documents, such

as the “ration card” issued for food subsidies, as their

primary source of identification; estimates suggest that

more than 85percent of the population had ration cards

in 201112. Not only did 15percent of the population not

have any form of legally verifiable ID, but there was also no

way to authenticate and verify the identity of ration card

holders in real time at no cost. Today that has changed

dramatically: more than 1.2billion Indians have Aadhaar

digital identification, up from 510million in 2013.

1

Aadhaar

has become the largest single digital ID programme in the

world—and a powerful catalyst of digital adoption more

broadly in India.

Aadhaar is a 12-digit number that the Unique Identification

Authority of India issues to Indian residents based on

their biometric and demographic information. To obtain

an Aadhaar ID, applicants permit the authority to record

their fingerprints, scan their irises, take their photograph,

and record their name, date of birth or age, gender,

and address.

2

The IDs were created to provide all residents of India with

high-assurance, unique, digitally verifiable means to prove

who they are. An important beneficial impact has been the

potential to reduce loss, fraud, and theft in government

benefits programs by enabling the direct transfer of

benefits to bank accounts. This use has helped spur

consumer adoption of digital services. Almost 870million

bank accounts were linked to Aadhaar by February 2018,

compared with 399million in April 2017 and 56million in

January 2014.

3

Arecent survey shows that 85percent of

people who opened a bank account between 2014 and

1

Unique Identification Authority of India, April 2018.

2

About Aadhaar, Unique Identification Authority of India, uidai.gov.in.

3

UIDAI; IDinsight.

4

Ronald Abraham et al., State of Aadhaar report 2017–18, IDinsight, May 2018.

5

For a discussion of the potential economic impact, along with challenges and risks, of digital ID globally,

seeDigital identification: A key to inclusive growth, McKinsey Global Institute, January 2019.

6

What is Aadhaar? India’s controversial billion-strong biometric database, SBS News, September 27, 2018.

7

Manveena Suri, “Aadhaar: India Supreme Court upholds controversial biometric database”, CNN.com,

September 26, 2018.

2017 used Aadhaar as their identification. Inall, 82percent

of public benefits disbursement accounts are now linked

to Aadhaar, which has reduced fraud and leakage.

4

A suite of open application program interfaces (APIs) is

linked to Aadhaar. For example, the Unified Payments

Interface platform integrates other payment platforms

in a single mobile app that enables quick, easy, and

inexpensive payments among individuals, businesses, and

government agencies. DigiLocker permits users to issue

and verify digital documents, obviating the need for paper.

Digital ID systems globally are not without controversy:

some worry about their ability to track personal information

that could be misused in the hands of malicious entities,

and the risk of systematic exclusion is also a concern.

5

Aadhaar’s design follows a data minimisation policy that

allows collection and storage of basic demographic data

only. Thereafter, whenever any ID-requesting party asks

for verification, the Aadhaar system issues only a yes or no

based on the biometric match. It does not store or share the

reason for the verification or details of any transaction. The

risk arises when other databases not belonging to Aadhaar

are seeded with Aadhaar numbers. For example, an

individual’s bank account details can be pieced together,

and the availability of that information can give rise to

fraudulent practices.

India’s Supreme Court ruled in September 2018 that

Aadhaar does not violate the right to privacy and may

legally be required to obtain government services.

6

However, in its 1,400-page ruling, the court also struck

down a section of the Aadhaar law stipulating that private

companies could require potential customers to provide an

Aadhaar ID for services such as opening a bank account,

obtaining mobile phone SIM cards, or enrolling children

in school.

7

To make such uses permissible on a voluntary

basis, the government would need to amend the relevant

laws or modify authentication processes.

4 Digital India: Technology to transform a connected nation

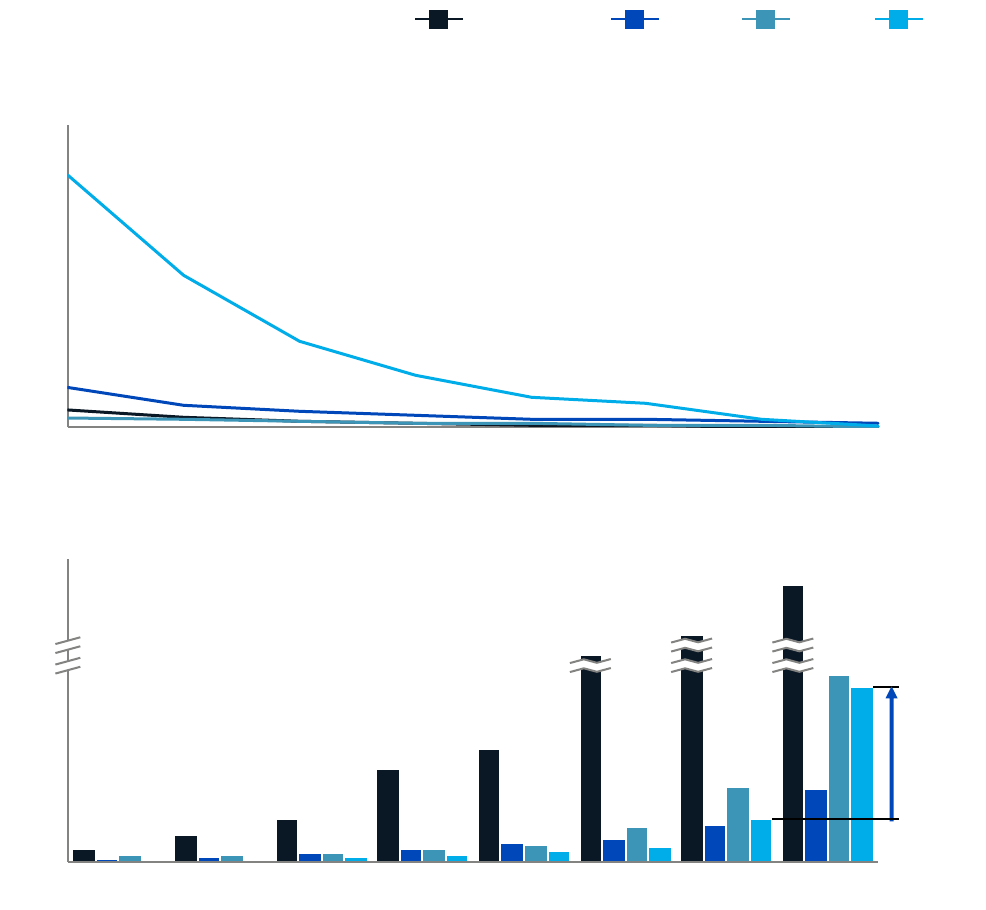

Exhibit E3

India’s data usage quadrupled in one year as prices fell.

1

In data published by the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India for September 2018, consumption per unique subscriber is shown to have

increased to 8,320 MB, putting India on pace to more than quadruple its average consumption again from 2017 to 2018.

SOURCE: Analysys Mason, January 9, 2019; UN Database; McKinsey Global Institute analysis

Exhibit 1

2017

50

2010 1211 1513 1614

0

10

20

30

40

60

India’s data usage quadrupled in one year as prices fell

Source: Analysys Mason, January 9, 2019; UN Database; McKinsey Global Institute analysis

1. In data published by the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India for September 2018, consumption per unique subscriber is shown to have

increased to 8,320 MB, putting India on pace to more than quadruple its average consumption again from 2017 to 2018.

!"#$%&#'()*'+

D

ata price

P

er GB of data (% of monthly GDP per capita)

D

ata quantity

P

er connection, per month (MB)

United States

Brazil China India

1

1,000

4,000

0

3,500

500

1,500

11 13

1,622

12 20172010

397

1614 15

4x

5Digital India: Technology to transform a connected nation

India’s digital divide is narrowing, and all states have much

room to grow

With both private and public-sector action promoting digital usage, India’s states have started

bridging the digital divide. Lower-income states are showing the fastest growth in internet

infrastructure, such as base tower stations and the penetration of internet services to new

customers. While low and moderate-income states as a group accounted for 43percent of all

base tower stations in India in 2013, they accounted for 52percent of the incremental towers

installed between 2013 and 2017.

9

Low-income states like UttarPradesh, Madhya Pradesh,

and Jharkhand were among the five fastest-growing states in internet penetration between

2014 and 2018; Uttar Pradesh alone added more than 36million internet subscribers in that

period. Ordinary Indians in many parts of the country—including small towns and rural areas—

can read the news online, order food delivery via a phone app, video chat with a friend (Indians

log 50million video-calling minutes a day on WhatsApp), shop at a virtual retailer, send money

to a family member through their phone, or watch a movie streamed toa handheld device.

Even after these advances, India still has plenty of room to grow in digital terms. Just over

40percent of the populace has an internet subscription.

10

Despite the growth of digital

financial services, close to 90percent of all retail transactions, by number, are still in cash.

11

Only 5percent of trade is transacted online, compared with 15percent in China in 2015.

12

Looking ahead, India’s digital consumers are poised for robust growth. By our estimates,

India could add as many as 350million smartphones by 2023.

Indian businesses are digitising rapidly but not evenly

Against this backdrop of rapid consumer internet adoption, India’s businesses have a

relatively uneven pattern of digitisation. We surveyed more than 600 firms to determine

the level of digitisation as well as the underlying traits, activities, and mind-sets that drive

digitisation at the firm level. We used each company’s answers to score its level of digitisation

on a scale of 0 to 100 and created the MGI India Firm Digitisation Index. Companies in the top

quartile, which we characterise as digital leaders, had an average score of 58.2, while those in

the bottom quartile, the digital laggards, averaged 33.2. Themedian score was 46.2.

A higher score indicates a company uses digital more extensively in day-to-day operations

(such as implementing customer relationship management systems or accepting digital

payments) and in a more organised manner (for example, by having a separate analytics team

or centralised digital organisation) than companies with lower scores. Our survey found that, on

average, digital leader firms outscored other firms by 70percent on strategy dimensions (for

example, responsiveness to disruption and investment in digital technologies), by 40percent

on organisation dimensions (such as level of executive support and use of key performance

indicators), and by 31percent on capability dimensions (including use of technologies such as

CRM and enterprise resource planning solutions, and adoption of digital payments).

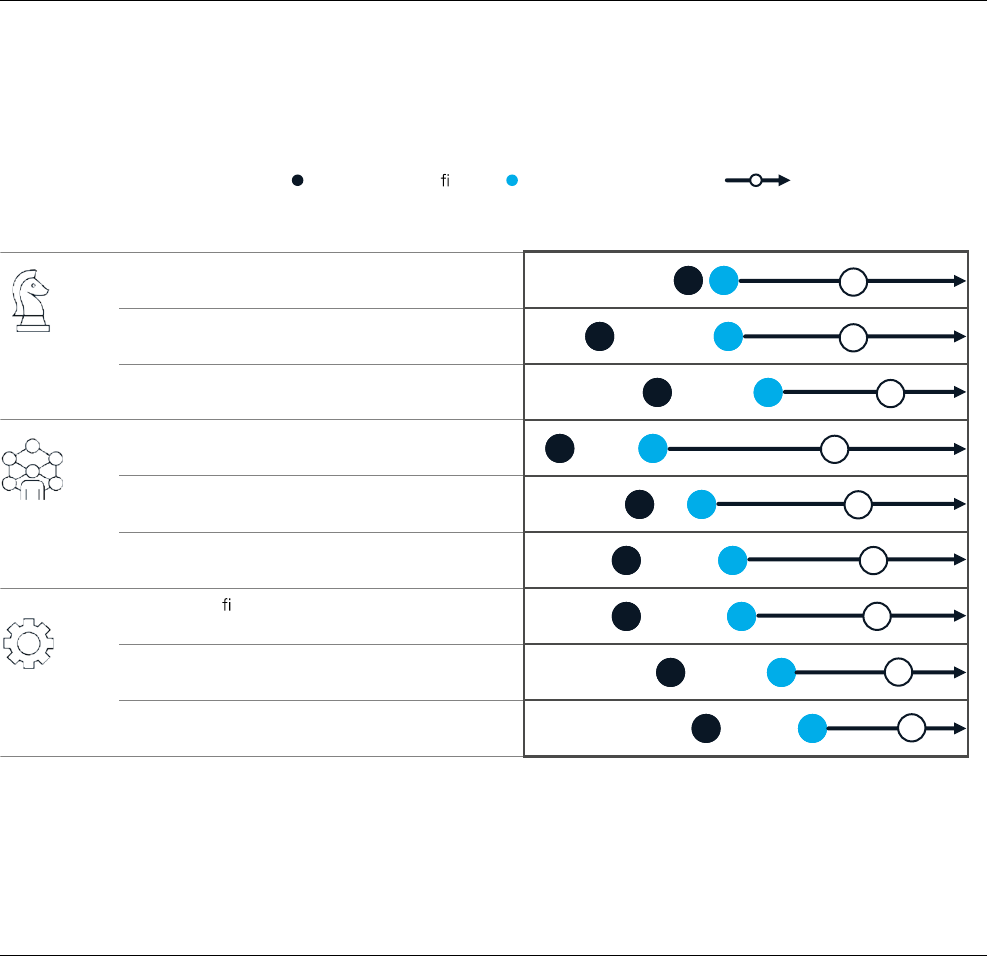

Differences in digital adoption within sectors are greater than those across sectors.

Whilesome sectors have more digitally sophisticated companies than others, top-quartile

companies can be found in all sectors—even those sometimes considered resistant to

technology, such as transportation and construction. Conversely, sectors such as information

and communications technology (ICT), professional services, and education and healthcare,

which have more digitised firms on average, are represented in the bottom quartile of

adoption (Exhibit E4).

9

States are categorised based on their per capita GDP relative to the country’s: “very high income” states have per capita

GDP more than twice India’s average; “high income”, 1.2 to two times; “moderate income”, 0.7 to 1.2 times; and “low

income”, less than 0.7 times.

10

Indian telecom services performance indicator report, June-September 2018, Telecom Regulatory Authority of India.

11

“Digital payments in India to reach $1trillion by 2023: Credit Suisse”, Economic Times, February 15, 2018.

12

Euromonitor International Retailing Edition 2019.

6

Digital India: Technology to transform a connected nation

Exhibit E4

Digitisation levels vary more within sectors than across sectors among large Indian rms.

India Firm Digitisation Index

1

1

Based on 50-question survey of 220 large companies (5billion rupees or $70million annual revenue). The survey seeks to determine

level of digitisation as well as the underlying traits, activities, and mindsets that drive it. Firms are scored based on their responses on

dimensions related to digital strategy (eg, responsiveness to disruption, investment in digital technologies); digital organisation (eg, level

of executive support, use of key performance indicators); and digital capabilities (eg, use of technologies like CRM and ERP, or adoption

of digital payments).

2

ICT comprises telecom services providers, media and information technology companies.

3

Financial services comprises banks, finance, and insurance companies.

4

Real estate and construction comprises construction companies, real estate developers, and real estate brokerage firms.

5

Professional services comprises companies in the fields of consulting, architecture, and stock trading, among others.

6

Education and health comprises firms in the fields of health services, pharmaceuticals, and education services.

7

Manufacturing comprises firms in manufacturing of textiles, food processing, metal and metal products, petroleum and related

products, and others.

8

Trade comprises companies trading, both wholesale and retail, commodities (eg, automobiles, sanitary wares).

9

Transport comprises firms in logistics and passenger transport.

10

Leaders are top quartile firms in terms of firm digitisation index, while laggards are in the bottom quartile.

SOURCE: McKinsey India firm digitisation survey, May 2017; McKinsey Global Institute analysis

Exhibit 12

India Firm Digitisation Index

1

Digitisation levels vary more within sectors than across sectors among large Indian rms

Source: McKinsey India rm digitisation survey, May 2017; McKinsey Global Institute analysis

1. Based on 50-question survey of 220 large companies (5 billion rupees or $70 million annual revenue). The survey seeks to determine level of

digitisation

as well as the underlying traits, activities, and mindsets that drive it. Firms are scored based on their responses on dimensions related to digital

strategy

(eg, responsiveness to disruption, investment in digital technologies); digital organisa

tion (eg, level of executive support, use of key performance

indicators); and digital capabilities (eg, use of technologies like CRM and ERP, or adoption of digital payments).

2. Leaders are top quartile rms in terms of rm digitisation index, while laggards are in the bottom quartile.

3. ICT comprises telecom services providers, media and information technology companies.

4. Financial services comprises banks, nance, and insurance companies.

5. Real estate and construction comprises construction companies, real estate developers, and real estate brokerage rms.

6. Professional services comprises companies in the elds of consulting, architecture, and stock trading, among others.

7. Education and health comprises rms in the elds of health services, pharmaceuticals, and education services.

8. Manufacturing comprises rms in manufacturing of textiles, food processing, metal and metal products, petroleum and related products, and

others.

9. Trade comprises companies trading, both wholesale and retail, commodities (eg, automobiles, sanitary wares).

10. Transport comprises rms in logistics and passenger transport.

33

37

15

16

22

21

35

15

71

57

66

74

63

73

54

53

60

10

0

70

20

30

40

50

80

Median score in sector

Highest score in sector

Lowest score in sector

!"#$%&#'()*'+

ICT

3

Financial

services

4

Real estate

and

construc-

tion

5

Profes-

sional

services

6

Education

and health

7

Manufac-

turing

8

Trade

9

Transport

10

Sector median

digitisation score

50 48 47 47 46 45 44 43

Leaders

% of rms in sector

41 28 40 36 24 21 5 10

Laggards

% of rms in sector

26 17 15 20 29 27 45 19

Digital laggards

2

<41

Digital leaders

2

>52

7Digital India: Technology to transform a connected nation

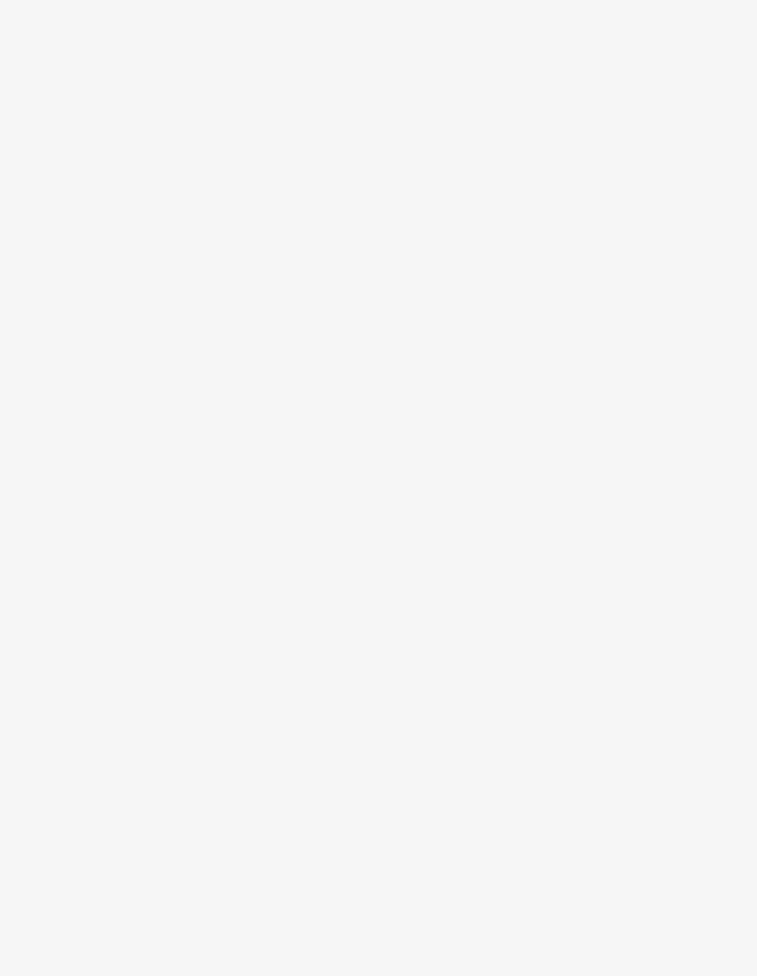

Digital leaders share common traits that digital laggards can emulate

India’s digital leaders share common traits in digital strategy, organisation, and capabilities,

but they still have room to improve across all three areas, from CEO support for digital

initiatives to use of customer relationship management systems and other digital capabilities

(Exhibit E5).

— Digital strategy: Leading digital companies in India adopt strategies that make them

stand out from their peers in several ways. They centre their strategies on digital, let

digital technologies shape how they engage with customers, and invest more heavily in

digital than their peers. These firms are 30percent more likely than bottom-quartile firms

to say they fully integrate their digital and overall strategies, and 2.3 times more likely to

sell their products through e-commerce platforms. Top-quartile firms are 3.5 times more

likely than bottom-quartile firms to say that digital disruptions led them to change their

core operations. Digital leaders also make digital investment a priority. Top-quartile firms

are 5.5 times more likely than bottom-quartile firms to outspend their peers on digital

initiatives and 40percent more likely to consider digital a top priority for investment.

Exhibit E5

India’s digital leaders still have ample room for improvement in many areas.

1

“Leaders” are firms scoring within the top quartile of MGI’s India Firm Digitisation Index.

2

Results of a survey conducted across 220 large firms in India with revenue of 5billion rupees, or $70million.

SOURCE: McKinsey India firm digitisation survey, May 2017; McKinsey Global Institute analysis

Exhibit 14

India’s digital leaders still have ample room for improvement in many areas

Source: McKinsey India rm digitisation survey, May 2017; McKinsey Global Institute analysis

1. “Leaders” are rms scoring within the top quartile of MGI’s India Firm Digitisation Index.

2. Results of a survey conducted across 220 large rms in India with revenue of 5 billion rupees, or $70 million.

% of rms responding

10 6020 30 40 50 70 80 100900

30

17

37

45

46

55

8

29

26

40

23

33

47

23 49

58

41 65

Strategy

Has a digital strategy that is fully integrated with the

overall strategy

Has changed core operations in response to

disruption

Believes they invest more in digital than peers do

Organisation

Has a centralised, company-wide digital

organisation

CEO supports and is directly involved in digital

initiatives

Has a distinct, stand-alone analytics team with the

appropriate talent

Capabilities

Uses the Uni ed Payments Inter-face (UPI) for

interban

k transfers

Has implemented a Customer Relationship

Management system

Makes extensive use of digital channels to reach

customers

% of leaders not

reporting this attribute

% of digital leaders

reporting this attribute

1

% of non-leader rms

reporting this attribute

42

71

60

53

51

35

55

45

54

8 Digital India: Technology to transform a connected nation

— Digital organisation: Many more digital leaders than laggards have a single business unit

that manages and coordinates digital initiatives for the entire company. Top-quartile firms

are 14.5 times more likely than bottom-quartile firms to centralise digital management,

and five times more likely to have a stand-alone, properly staffed analytics team. Top-

quartile firms are also 70percent more likely than bottom-quartile firms to say their

CEO is “supportive and directly engaged” in digital initiatives.

— Digital capabilities: Top-quartile firms are 2.6 times more likely than bottom-quartile

firms to use customer relationship management software, for example, and 2.5 times

more likely to coordinate the management of their core business operations by using an

enterprise resource planning system. Digital leaders also optimise their digital marketing.

Our survey shows that top-quartile companies are 2.3 times more likely than bottom-

quartile firms to use search engine optimisation, and 2.7 times more likely to use social

media for marketing.

The gap between digital leaders and other firms is not insurmountable. In some cases, even

when the difference is large, companies may be able to begin closing it by digitising in small,

relatively simple ways. Social media marketing is a good example. Bottom-quartile firms

are 70percent less likely than top-quartile businesses to use social media to attract and

serve new customers, and less than half as likely to use e-commerce or listing platforms.

However, these sales channels are cheap and easily accessible, and a business owner with

a smartphone and a high-speed internet connection will encounter few barriers to taking

advantage of them.

Small businesses are closing the digital gap with larger firms

and are ahead of them in accepting digital payments

Large companies (defined in our survey as having revenue greater than 5billion rupees,

orabout $70million) have the financial resources and expertise to invest in some advanced

technologies, such as artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things, but growing high-speed

internet connectivity and shrinking data costs are opening digital opportunities for many

small-business owners and sole proprietors.

Indeed, our survey found that small businesses are ahead of large companies in accepting

digital payments. Among small firms, 94percent said they accept payment by debit or

credit card, compared with only 79percent of big firms; for digital wallets, the figures

were 78percent versus 49percent. Small companies also are more willing to use digital

technologies such as video conferencing and chat to support their customers.

Our survey found that 70percent of small firms have built their own websites to reach clients,

compared with 82percent of large firms, and are just about as likely as those big companies

to have optimised their websites for mobile devices. Small firms are less likely than big firms

to buy display ads on the web (37percent versus 66percent), but they are ahead of big

companies in connecting with customers via social media and are more likely to use search

engine optimisation. More than 60percent of the small firms surveyed use LinkedIn to hire

talent, and about half say most of their employees need to have basic digital skills. While only

51percent of smaller firms said they “extensively” sell goods and services via their websites

(compared with 73percent of big businesses), small businesses use e-commerce platforms

and other digital sales channels just as much as large firms and are equally likely to receive

orders through digital channels such as WhatsApp.

Digital applications have potential to create significant economic

value for India but will require new skills and labour redeployment

Firms in India that innovate and digitise rapidly will be better placed to tap into a large

connected market of up to 700million smartphones and about 800million internet users

by 2023. In the context of rapidly improving technology capabilities and declining data

costs, technology-enabled business models could become omnipresent across sectors and

activities in India over the next decade. That will likely create significant economic value in

each of these sectors. At the same time, the nature of work will change and require new skills.

94%

Percentage of small

businesses accept debit

or credit card payments

700m

Number of estimated

smartphones in India

by 2023

9Digital India: Technology to transform a connected nation

Core digital sectors could more than double in size by 2025, and

each of several newly digitising sectors could contribute $10billion

to $150billion of economic value

We consider economic impact across three types of sectors. First are core digital sectors,

such as ITBPM; digital communication services, including telecom services; andelectronics

manufacturing. Second are newly digitising sectors that are not traditionally considered

part of India’s digital economy but have the potential to innovate and adopt digital rapidly,

such as financial services, agriculture, healthcare, logistics, and retailing. Third are activities

related to government services and labour markets, which can be intermediated using digital

technologies in new ways.

India’s core digital sectors accounted for about $170billion—or 7percent—of GDP in

201718.

13

This comprises value added from sectors that already provide digital products and

services at scale, such as ITBPM ($115billion), digital communication services ($45billion),

and electronics manufacturing ($10billion). We estimate that these sectors could grow

significantly faster than GDP, and their value-added contribution could range from $205billion

to $250billion for ITBPM, $100billion to $130billion for electronics manufacturing, and

$50billion to $55billion for digital communication services, totalling between $355billion and

$435billion and accounting for 8 to 10percent of India’s GDP in 2025.

Alongside these already digitised sectors and activities, India stands to create more value if

it succeeds in nurturing new and emerging digital ecosystems in sectors such as agriculture,

education, energy, financial services, healthcare, and logistics. The benefits of digital

applications to productivity and efficiency in each of these newly digitising sectors are

already visible. For example, in logistics, tracking vehicles in real time has enabled shippers to

reduce fleet turnaround time by 50 to 70percent.

14

Similarly, digitising supply chains allows

companies to reduce their inventory by up to 20percent. Farmers can cut the cost of growing

rice by 15 to 20percent using data on soil conditions that enables them to minimise the use of

fertilisers and other inputs.

15

In cross-cutting areas such as government services and the markets for jobs and skills, digital

technologies can also create significant value. For example, shifting government transactions,

including subsidy transfers and procurement, online can enhance public-sector efficiency and

productivity, and creating online marketplaces that bring together workers and employers could

considerably improve the performance of India’s fragmented and largely informal job market.

Unlocking this value will require widespread adoption and implementation. The economic

value will be proportionate to the extent that digital processes permeate organisations and

their marketing and service delivery channels, shop floors, and supply chains. Our estimates

of potential economic value for each sector vary depending on adoption rates by 2025; for

example, in areas where the readiness of India’s firms and government agencies is low and

considerable effort will be required to catalyse broad digitisation, adoption may be as low as

20percent. Where private-sector readiness is relatively high and government policy is already

supportive of large-scale digitisation, adoption could be as high as 80percent.

13

Estimates based on industry revenue and cost structures and growth trends.

14

Who we are, Rivigo, rivigo.com.

15

Pinaki Mondal and Manisha Basu, “Adoption of precision agriculture technologies in India and in some developing

countries: Scope, present status and strategies”, Progress in Natural Science: Materials International, June 2009,

Volume 19, Issue 6.

10

Digital India: Technology to transform a connected nation

Box E2.

Our methodology for sizing economic value

Our research seeks to analyse and quantify the potential economic impact of digital

technology and applications in India over the coming years.

The core digital sectors we describe (ITBPM, digital communication services, and

electronics manufacturing) are already considered part of India’s digital economy,

and their GDP contribution is measured based on conventional revenue, expense,

and value-added metrics.

Economic data are not available for technology-based business models and applications

in newly digitising sectors—such as agriculture, education, energy, financial services,

manufacturing, healthcare, logistics, and retail—because national income accounts do

not yet track them separately. For these areas, we create broad estimates of potential

economic value in the future. We use a value-impact approach to understand and estimate

the potential effect of digital adoption on productivity based on micro evidence from

sectors and firms. We identify discrete use cases and estimate their potential impact by

quantifying the productivity gains possible if they were to scale up and achieve moderate

to high levels of adoption. Productivity gains are estimated by measures such as greater

output using the same resources, cost savings, time savings, and new sources of capital

and labour that could become available with the implementation of digital technologies.

We do not estimate potential GDP impact because the accounting and marketisation of

productivity gains remain uncertain and hard to predict. For example, it is unclear whether

time saved will convert into productive and paying jobs, and whether new digital services

will generate consumer surplus accruing to users of technologies or paid products that

yield revenue to producers. Nevertheless, we believe these estimates provide a sense of

the order of magnitude of the impact that digitisation represents for an economy of the

scale and breadth of India’s.

All our estimates are in nominal dollars in 2025 and represent scope for economic value

creation in that year. They do not represent market revenue or profit pools for individual

players; rather, they are estimates of end-to-end value to the whole system.

Our estimates of economic value in 2025 represent potential; they are not a prediction.

The pace of India’s progress will depend on government policies and private-sector

action. Realising the economic value estimated would necessitate investment in digital

infrastructure and ecosystems, complementary investment in physical infrastructure

and productive capacities, and education and training of the workforce.

In all, we estimate that India has the potential to create considerable economic value by 2025:

$130billion to $170billion in financial services (including digital payments); $50billion to

$65billion in agriculture; $25billion to $35billion in retail and e-commerce (including supply

chain); $25billion to $30billion in logistics and transportation; and roughly $10billion in areas

such as energy and healthcare (Exhibit E6). Greater digitisation of government services and

benefits transfers could yield economic value of $20billion to $40billion combined and up to

$70billion from more efficient skill training and job market matching using digital platforms.

The economic value is estimated as a range (seeBoxE2, “Ourmethodology for sizing

economic value”). While these estimates underscore large potential value, realisation of this

value is not guaranteed: losing momentum on the government policies that enable the digital

economy would mean India could realise less than half of the potential value by 2025.

11Digital India: Technology to transform a connected nation

Exhibit E6

Digital technologies can create signicant economic value in India in 2025.

Exhibit E6

Digital technologies can create signicant economic value in India in 2025

Source:

McKinsey Global Institute analysis

Others

...but India will need to

seize the opportunity.

Newly digitised sectors

show the biggest

growth potential...

Maxiumum potential

value

Reduced potential value

of digitisation due to

ineective policies

and/or low private

sector participation

IT business process mgmt.

Financial services

3

Job and skills

Logistics

Digital comms services

Government e Marketplace

Education

Energy

Healthcare

Agriculture

Retail

Direct benet transfer

Electronic manufacturing

Current

economic value

($ billions)

Maximum potential

value by 2025

($ billions)

Core digital

services

Newly digitising

sectors

Digital govern-

ment & labour

markets

100%

Sector value potential ranked from highest (IT) to lowest (healthcare)

1

McKinsey Global Institute value estimates in each category are based on the

“value-impact approach” and focus on the potential eect of adoption of the

considered digital applications on productivity. Discrete use cases were identied

with their potential impact, in terms of greater output, time, or cost saved; these

estimates were multiplied by their adoption rates to create a macro picture of

potential economic gains for each application, scaled up for each sector.

All of our estimates are in nominal US dollars in 2025 and represent scope for

economic value creation in that year. They do not represent market revenue,or

prot pools for individual players; rather they are estimates of end-to-end value to

the system as a whole. Some of the economic value we size may or may not

materialise as GDP or on market-based exchanges.

Potential estimate of economic value from ow based lending, plus economic

value created through digital payments.

Excluding eects of business digitisation in nancial services, agriculture,

education, retail, logistics, energy, and healthcare, which are listed separately.

Potential estimate of economic value from precision agriculture, digital farmer

nancing and universal agricultural marketplace.

Potential estimate of economic value from online talent platforms.

Estimation for 2025 includes value addition from visual broadband services,

plus digital media and entertainment.

Potential estimate of economic value from e-commerce and digital supply chain.

For estimation purposes in the report, etail is considered for e-commerce. If

broader denition of e-commerce is used (etail + etravel), current value becomes

$5billion and future potential becomes $28 billion to $40 billion. This assumes

that etravel becomes 25 percent of broader e-commerce by 2025, consistent

with trend observed in China.

Potential estimate of economic value from ecient logistics and shared transport.

Potential estimate of economic value from digitally enabled power distribution

and smart grid with distributed generation.

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

115 <1 10 <1

<145<1<1

3 <1

<15

<1 <1

5055

35

70

30 25 15

15 10

250 130 90

70

Job and skills

Government eMarketplace

25x

Financial services

Logistics

Agriculture

Education

170x

50x

70x

30x

50%

170

2 1

5

8 9 10

76

12 Digital India: Technology to transform a connected nation

4

Business digitisation

(including manufacturing IoT)

12 Digital India: Technology to transform a connected nation

Productivity unlocked by digital applications could create up to

65million jobs for Indians by 2025, but up to 45million workers

will need retraining and redeployment

Prior MGI research on the effects of automation and other technologies on work has found

that while some jobs will be displaced, and others created, most occupations will change as

machines complement humans in the workplace.

16

That in turn will require a new focus on

retraining. For India, we estimate that the new digital economy may render obsolete all or

parts of 40million to 45million existing jobs by 2025, particularly those in highly predictable,

nonphysical activities, such as the work of data-entry operators, bank tellers, clerks, and

insurance claims- and policy-processing staff. Consequently, many millions who currently

hold these jobs will need to be retrained and redeployed.

At the same time, heightened productivity and increased demand generated by digital

technology applications may create enough new jobs to offset that substitution and

employ more workers if the requisite training and investments are made. We estimate

that 60million to 65million could be created through the direct impact of productivity-

boosting digital applications.

New skills will be needed for jobs of the future

Jobs of the future will be more skill-intensive. The need for functional digital literacy will

increase across the board. For example, many more delivery workers will need to use apps

to navigate their way around the city, shop floor workers will need to understand and respond

to the output of precision control systems, farm advisory agents will need to read intelligent

apps on their tablets and discuss implications with farmers, and health workers will need to

learn how to extract and upload data into intelligent health management information systems.

Routine tasks like data processing will be increasingly automated.

Along with rising demand for skills in emerging digital technologies (such as the Internet

of Things, artificial intelligence, and 3D printing), demand for higher cognitive, social,

and emotional skills, such as creativity, unstructured problem solving, teamwork, and

communication, will also increase. These are skills that machines, for now, are unable to

master. As the technology evolves and develops, individuals will need to constantly learn

and relearn marketable skills throughout their lifetime. India will need to create affordable

and effective education and training programs at scale, not just for new job market

entrants but also for midcareer workers.

Four sectors in which digital forces can have a transformative effect

To capture the potential economic value that we size at a macro level, businesses will

need to deliver digital technologies at a micro level: that is, use digital technologies to

fundamentally change the way individuals and businesses interact and perform day-to-day

activities. We examine the potential shifts in interactions between individuals and institutions

(predominantly businesses, although government agencies also play important roles in

many value chains). These interactions will shift because of three digital forces: those that

allow people to connect or collaborate, transact, and share information; those that enable

organisations to automate routine tasks to increase productivity; and those that provide

the tools for organisations to analyse data to make insights and improve decision making.

Theinterplay of these three forces will lead to the emergence of new data ecosystems in

virtually every business sector or domain, spurring new products, services, and channels,

and creating economic value for consumers as well as components of the ecosystem that

best adapt their business models.

16

See Jobs lost, jobs gained: Workforce transitions in a time of automation, McKinsey Global Institute, December 2017.

For this report, we used similar analysis with different time frames.

Exhibit E6

Digital technologies can create signicant economic value in India in 2025

Source:

McKinsey Global Institute analysis

Others

...but India will need to

seize the opportunity.

Newly digitised sectors

show the biggest

growth potential...

Maxiumum potential

value

Reduced potential value

of digitisation due to

ineective policies

and/or low private

sector participation

IT business process mgmt.

Financial services

3

Job and skills

Logistics

Digital comms services

Government e Marketplace

Education

Energy

Healthcare

Agriculture

Retail

Direct benet transfer

Electronic manufacturing

Current

economic value

($ billions)

Maximum potential

value by 2025

($ billions)

Core digital

services

Newly digitising

sectors

Digital govern-

ment & labour

markets

100%

Sector value potential ranked from highest (IT) to lowest (healthcare)

1

McKinsey Global Institute value estimates in each category are based on the

“value-impact approach” and focus on the potential eect of adoption of the

considered digital applications on productivity. Discrete use cases were identied

with their potential impact, in terms of greater output, time, or cost saved; these

estimates were multiplied by their adoption rates to create a macro picture of

potential economic gains for each application, scaled up for each sector.

All of our estimates are in nominal US dollars in 2025 and represent scope for

economic value creation in that year. They do not represent market revenue,or

prot pools for individual players; rather they are estimates of end-to-end value to

the system as a whole. Some of the economic value we size may or may not

materialise as GDP or on market-based exchanges.

Potential estimate of economic value from ow based lending, plus economic

value created through digital payments.

Excluding eects of business digitisation in nancial services, agriculture,

education, retail, logistics, energy, and healthcare, which are listed separately.

Potential estimate of economic value from precision agriculture, digital farmer

nancing and universal agricultural marketplace.

Potential estimate of economic value from online talent platforms.

Estimation for 2025 includes value addition from visual broadband services,

plus digital media and entertainment.

Potential estimate of economic value from e-commerce and digital supply chain.

For estimation purposes in the report, etail is considered for e-commerce. If

broader denition of e-commerce is used (etail + etravel), current value becomes

$5billion and future potential becomes $28 billion to $40 billion. This assumes

that etravel becomes 25 percent of broader e-commerce by 2025, consistent

with trend observed in China.