memory

testimony

recollect

record

understand

history

life stories

listen

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Oral History

Interview Guidelines

Written by

Oral History Staff

Joan Ringelheim

, Director

Oral History

Arwen Donahue

Elizabeth Hedlund

Amy Rubin

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Oral History

Interview Guidelines

Oral History Interview Guidelines

Printed 1998

Revised 2007

No unauthorized use without permission.

Requests for permission to use portions of this

document should be made in writing and sent to:

Office of Copyright Coordinator

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

100 Raoul Wallenberg Place, SW

Washington, DC 20024-2126

For information about the Museum’s

Oral History Branch, contact:

Program Management Assistant, Oral History

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

100 Raoul Wallenberg Place, SW

Washington, DC 20024-2126

202.488.6103

For further information about

the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum,

call 202.488.0400.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Foreword i

Introduction v

I. THE PRELIMINARY INTERVIEW 1

Purpose of the Preliminary Interview

Creating a Questionnaire

Providing Options for the Interviewee

Conducting the Preliminary Interview

How Much Detail?

Timing of the Preliminary Interview

Assessing the Preliminary Interview

Summarizing the Preliminary Interview

II. MAKING ARRANGEMENTS

FOR THE INTERVIEW

7

Contacting the Interviewee

Scheduling the Interview

Interview Note

T

ak

er

Individuals Present at Interview

Legal and Ethical Considerations

III.

C

ONDU

CTING RESEARCH

1

1

Set Aside Time for Research

Review Interviewee’s Experiences

Important Items to Research

Things You Can Do at Home

Visit a Library or Research Facility

Maps

Other R

esources for Locating Places

Expanding Your Search for Resources

Using the Museum’

s Resources

If You Need Clarification

Challenges

R

esearc

h List

When to Stop

IV. PREPARING QUESTIONS 21

Notes on Preparing Questions

Organizing Questions

Using Questions in the Interview

V. SUGGESTED THEMES 23

Family/Occupation/Education

Religion and Politics

G

ender

VI. SUGGESTED QUESTIONS 25

Prewar Life

The First Questions

Childhood Recollections

Nazi Rise to Power

Holocaust/Wartime Experiences

Ghettos and Transit Camps

Labor Camps, Prisons, Concentration/Extermination Camps

Hiding/Passing and Escaping

Resistance

Postwar Experiences

Liberation

Displaced Persons Camps

Emigration/Immigration

Beyond the War/Life After the Holocaust

VII. C ONDUCTING THE INTERVIEW 39

Arrival at the Interview

Commencing the Interview

Open-Ended and Specific Questions

Interjecting vs. Interrupting

Non-Verbal Responses

Chronology of the Interview

Taking Breaks

P

ro

viding Historical Context

Allocation of Time in the Interview

Concluding the Interview

Post-Holocaust Interviews

Before L

eaving the Interview

Donation of Artifacts

VIII.TECHNICAL GUIDELINES

FOR

A

UDIO INTERVIEWS

47

Cassette Tapes and Batteries

Labeling Tapes

Recording Equipment

Location/Setup

Recording Level

S

tarting to Record

Tape Slating

Monitoring the Recording

Technical Troubleshooting

IX. TECHNICAL GUIDELINES

FOR VIDEO INTERVIEWS

55

Studio/Location Setup

C

omposition

Lighting

Sound

Other Technical Considerations

T

ape Slating

The Interviewee

The Interviewer

X. AFTER THE INTERVIEW 59

Thanking the Interviewee

Creating Interview Finding Aids

Use and Storage of Tapes

Donating the Interview to the Museum

APPENDIX 1: Sample Preliminary Interview Questionnaire 61

APPENDIX 2: Sample Preliminary Interview Summary 75

APPENDIX 3: Sample Interviewee Overview 77

APPENDIX 4: Sample Interview Research List 79

APPENDIX 5: Selected Bibliography 81

APPENDIX 6: Guidelines for Note Taking 85

APPENDIX 7:

Style Guidelines for Transcripts 91

APPENDIX 8: Guidelines for Copy Checking Transcripts 95

APPENDIX 9: Guidelines for Authenticating Transcripts 107

APPENDIX 10: Guidelines for Writing Summaries 123

page is blank

FOREWORD

ORAL HIS

T

OR

Y IN

TER

VIEW GUIDELINES

i

THE UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM is America’s

national institution for the documentation, study, and interpretation of

Holocaust history, and serves as this country’s memorial to the millions

of people murdered during the Holocaust.

The Holocaust was the state-sponsored, systematic persecution

and annihilation of European Jewry and other victims by Nazi Germany

and its collaborators between 1933 and 1945. Jews were the primary

victims—approximately six million were murdered; Roma and Sinti

(Gypsies), people with disabilities, and Poles also were targeted for

destruction or decimation for racial, ethnic, or national reasons.

Millions more, including homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Soviet

prisoners of war, and political dissidents also suffered grievous oppres-

sion and death under Nazi tyranny.

The Museum’s primary mission is to advance and disseminate

knowledge about this unprecedented tragedy, to preserve the memory

of those who suffered, and to encourage its visitors to reflect upon the

moral and spiritual questions raised by the events of the Holocaust as

well as their own responsibilities as citizens of a democracy.

ii UNITED S

T

ATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM

Chartered by a unanimous Act of Congress in 1980 and situated

adjacent to the National Mall in Washington, D.C., the Museum strives

to broaden public understanding of the history of the Holocaust

through multifaceted programs, including exhibitions; research and

publication; collecting and preserving material evidence, art, and arti-

facts relating to the Holocaust; annual Holocaust commemorations

known as the Days of Remembrance; distribution of educational mate-

rials and teacher resources; and a variety of public programming

designed to enhance understanding of the Holocaust and related issues,

including those of contemporary significance.

THE ORAL HISTORY BRANCH of the United States Holocaust

Memorial Museum produces video- and audiotaped testimonies of

Holocaust survivors, rescuers, liberators, resistance fighters, prosecu-

tors, perpetrators, and bystanders. The mission is to document and pre-

serve Holocaust testimonies as primary sources that will allow future

generations of students, researchers, teachers, and filmmakers to hear

and see the people who experienced, witnessed, or perpetrated the

genocidal policies and crimes of the Nazis and their collaborators. Part

of the Museum’s mandate is to produce oral histories that add to our

knowledge of all genocides.

The Museum has been collecting and producing oral histories

since 1989—four years before it opened. As of 2007, it has created an

archive of more than 9,000 audio and video testimonies, mostly in

English. Of those, the Museum itself has produced more than 2,000,

including more than 350 Hebrew-language interviews of Jewish

ORAL HIS

T

OR

Y IN

TER

VIEW GUIDELINES

iii

survivors who emigrated to Israel, and more than 100 of Jehovah’s

Witnesses who survived Nazi persecution. Although the Museum has

focused on producing videotaped testimonies of Jewish and

non-Jewish survivors—including Polish Catholics, Roma and Sinti

(Gypsies), political prisoners, homosexuals, and members of resistance

and partisan groups—the full range of interviews includes rescuers,

liberators, postwar prosecutors of Nazi crimes, displaced persons camp

relief workers, and members of the American Jewish Joint Distribution

Committee.

The unedited audio and videotapes, which are housed in the

Museum’s Archives, serve as resources for scholars, educators, film-

makers, and the public. In addition, the Museum now has more than

100 agreements with other organizations and individuals to house their

interviews within the Museum’s Archives.

Because of their powerful impact, edited segments of some inter-

views are included in the Museum’s permanent and special exhibitions

and public programs, as well as the Museum’s Wexner Learning Center

and Web site.

With the generous support of a number of grants, the Oral

History Branch is working to further its mission in building an oral his-

tory collection that represents the breadth of Nazi persecution. Projects

supported by the grants include the production of interviews with sur-

vivors living in Belarus, Greece, Macedonia, Poland, Ukraine, the

Czech Republic (with Roma), Israel, and the former Yugoslavia; inter-

views with witnesses, collaborators, and perpetrators in Estonia, former

Yugoslavia, France, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, the Nether-

iv UNITED S

T

ATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM

lands, Poland, Romania, and Ukraine; the Post-Holocaust Interview

Project, which traces the lives of survivors after the Holocaust; the pro-

duction of educational videos and other resources, and transcripts of

interviews to increase accessibility of our oral history collection; and the

ongoing preservation and cataloging of the collection.

ORAL HIS

T

OR

Y IN

TER

VIEW GUIDELINES

v

“The story reveals the meaning of what otherwise would

remain an unbearable sequence of sheer happenings.

”

—Hannah Arendt, Men in Dark Times

The interview journey through the Holocaust, or other such tragedies,

can be a painful and difficult one. To ask survivors of the Holocaust to

tell their stories is to ask them to describe the sights, smells, and sounds

of the human destruction they witnessed; to relive the deaths of family

and friends; and to describe the stories of their own survival. It is one

of the most difficult requests one person can make of another.

Yet, the oral history interviews that result from such requests pro-

vide glimpses into the history of the Holocaust that cannot be obtained

from documents or written records. While textual documents are essential

for the study of the Holocaust, an individual’s testimony can supple-

ment those documents by providing a detailed and personal look at a

historical event that may be underrepresented or even absent from writ-

ten works.

These Guidelines provide direction in all aspects of conducting

an interview, including making first contact with a potential interviewee,

INTRODUCTION

vi UNITED S

T

ATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM

conducting research and preparing questions for the interview, and

exploring technical aspects of recording interviews, both on audio and

videotape. The Guidelines also explore the intense interpersonal aspects

of the interviewer-interviewee relationship.

The interview process is an art, not a science. Although many

purposes can be served through standardized interviews, they bear little

resemblance to what we mean by an “oral history.” The oral history inter-

view is an attempt to provide a place for the interviewee to tell his or her

life story as he or she remembers it, and for the interviewer to ask ques-

tions that stimulate memory. The questions posed are very important, so

studying the subject areas in the person’s life is imperative. But the inter-

action between interviewee and interviewer can create a bond between

the two people that even ill-conceived questions cannot destroy. It is

within that bond that questions and answers flow, and that history is

revealed.

Defining an oral history interview this way creates a broad

mandate. It assumes that there is no single correct interview technique

or mode, and that different styles of interviewing are acceptable. This con-

cept of different styles can be clarified by comparing the interview

process with musical interpretation. If one listens to Horowitz,

Rubinstein, Argerich, and Guller playing a Chopin sonata, one will

hear the same piece of music, but it will sound different with each

pianist. Is one style right and the other wrong? Within certain limits,

one cannot admit to such a judgment; the issue of taste is a separate

matter. Since interviewing is an art, strategies for success must be var-

ied. Thus, the same person may give distinct, even divergent interviews

The

interview

process

is an art,

not a science.

Since

interviewing

is an art,

strategies

for success

must be

varied.

ORAL HIS

T

OR

Y IN

TER

VIEW GUIDELINES

vii

to different interviewers. The same or similar questions may produce

different answers because of the particular bond between an interviewer

and an interviewee. A variety of other circumstances also can affect the

interview—the setting, a personal difficulty, the weather. Even though

we are listening to one person’s story and trying to facilitate its telling,

the story will not necessarily sound the same on any given day, with any

given interviewer. For this reason, we maintain an expansive view of the

interview process to take advantage of these variables.

This is not to say that there are no limits or boundaries. For

example, an interviewer ordinarily should not argue with an interviewee.

Although interviewees make mistakes, it is not the role of interviewers

to correct them during interviews. Interviewees may say things that

stimulate conversation, but a conversation is not our aim. Rather, our

aim is to listen. Nevertheless, such limits should not constrain probing

questions when answers are too minimal, confusing, or even seem

mistaken, or when the interviewer thinks a question is necessary.

There is certain basic information that should be included in

each oral history interview that makes it accessible and usable for the

listener. Interviewers should not become so engrossed in the interview

process that they forget to ask for specific dates, names, and locations

that help place the interviewee’s experiences in historical context.

Genuine listening means that the interviewer hears the contours

of the story as it is being told. Often, important subjects in an inter-

viewee’s story are only hinted at; the interviewer must keep a constant

watch for these hints. The interviewer guides the interview, but does

not direct it. The interviewer is a facilitator of the interview, but does not

viii UNITED S

T

ATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM

manipulate it. This is not a place for ego to be exhibited; interviewers

should not use the interview to prove their knowledge. Comfort with

long silences is crucial to the listening process, and the timing of ques-

tions often requires the interviewer to sit through the silences of the

interviewee’s internal dialogue.

Because the content of these interviews is often tragic and terri-

fying, learning to listen also means that the interviewer needs to discern

his or her own fears. We sometimes intuitively want to protect ourselves

from what interviewees have to say. However, we must learn to listen to

everything about which the interviewee is able to speak. We must be

able to ask about everything in a way that invites response. This means

that difficult questions usually should be posed in a simple, straightforward

way. If we expose our fears by asking questions emotionally, people

often will respond to that emotion in an attempt to protect us, rather

than to answer the question we have posed. Therefore, we must respect

the interviewee’s limits, but not allow our own limitations to restrain

the stories that interviewees can tell us.

As interviewers, we travel with the interviewee. We try to see

more than the mere representation of the interviewee’s experiences. We

attempt to sit within the person’s story as if nothing else exists, and we

try to understand. We try to understand from the inside as if we were

there—much like the musician playing a piece of music. But we are

always outsiders, even while we share an intimacy with the interviewee.

It is important to balance our ability to listen empathetically with our

ability to listen carefully and critically.

Comfort

with long

silences is

crucial to

the listening

process.

As interviewers,

we travel with

the interviewee.

ORAL HIS

T

OR

Y IN

TER

VIEW GUIDELINES

ix

These Guidelines are intended to be used as a reference through-

out the interview process. They may be useful to the individual who

plans to conduct only a few interviews, to the newly established orga-

nization interested in initiating its own oral history project, or to the

already established organization looking for new insight and methods for

conducting oral history interviews. The Guidelines focus more on

preparing for and conducting the interview than on preserving it

archivally; however, we cannot overemphasize the importance of proper

post-production treatment of the interview (storage, preservation, cata-

loging, etc.). See Chapter X, After the Interview, for more information.

The Guidelines were originally created for the Oral History

Branch’s own interviewers, and often make specific references to

resources available for public use at the United States Holocaust

Memorial Museum. However, they also provide general advice that can

be applied to a wide variety of oral history projects, particularly those

with a Holocaust or genocide-studies orientation. They also provide

suggestions for finding resources in other libraries and resource centers.

ORAL HIS

T

OR

Y IN

TER

VIEW GUIDELINES

1

T

HE PRELIMINARY INTERVIEW

Chapter Overview

Purpose of the Preliminary Interview, 2

Creating a Questionnaire, 3

Providing Options for the Interviewee, 4

Conducting the Preliminary Interview, 4

How Much Detail?, 4

Timing of the Preliminary Interview, 5

Assessing the Preliminary Interview, 5

Summarizing the Preliminary Interview, 5

The Oral History Branch gathers names of potential interviewees from a

variety of sources. From these referrals, we elicit more information pri-

marily through the preliminary interview. Preliminary interviews often

are conducted by volunteers, who use a questionnaire as a guide to

ensure that no basic information is neglected. These preliminary inter-

views usually are conducted over the telephone. After each is

completed, the interviewer writes a summary of it, based on the

questionnaire and notes taken during the interview.

Preliminary interviews serve a variety of purposes. They help us

determine with whom to conduct full-length recorded interviews; they

provide an outline of the interviewee’s experiences on which research

for the full-length interview is based; and they provide at least a basic

summary of the interviewee’s experiences for future use in the event

1

I. THE PRELIMINARY INTERVIEW

Purpose

of the

Preliminary

Interview

that we are not able to follow up with a full-length interview. The inter-

viewee receives a copy of the typed preliminary interview summary, and

is asked to check it for accuracy.

After the telephone interview is completed, the file goes to the

Director of Oral History, who decides whether or not to conduct a

formal interview with that person. The Oral History Branch has

established some interview priorities, which are subject to change as

the representation in our collection changes.

In general, we look for persons who have compelling or interesting

stories. Clarity of memory and the ability to relate one’s experiences in a

coherent narrative often will take precedence over any priority list. At the

same time, if a person’s ability to tell his or her story is less than perfect, the

historical importance of a story may take precedence. Since we are limited

in the numbers of interviews we can do per year, we must use some cri-

teria for the choices we make, even though the criteria need to be flexible.

An essential par

t of the pr

eparation for a full-length, r

ecorded interview is the

preliminary interview (unless there already exists some detailed material about

the interviewee’s experiences, such as a written memoir). The information gath-

ered at the preliminary interview often is the basis for all other interview

preparation.

Most oral history projects cannot interview everyone who wishes to

be interviewed. Thus, another primary function of the preliminary interview

is to gather sufficient information to determine whether or not a full-length

video or audio interview should be conducted.

The aim of the preliminary interview is different from that of the

full-length recorded interview. The purpose of the preliminary interview is to

create an outline of the interviewee’s story. This limits the scope of a prelimi-

nary interview in comparison with a full-length interview. In a sense, the

2 UNITED S

T

A

TES HOL

OCA

UST MEMORIAL MUSEUM

T

HE PRELIMINARY INTERVIEW

Creating a

Questionnaire

preliminary interview is designed to be more clinical than the full-length

interview. For example, a questionnaire is very helpful for use in a preliminary

interview to guide the discussion and to ensure that the basic information has

been covered. Conversely, such a standard set of questions usually is not used

in a full-length interview. Rather, individualized questions are formulated

based on the preliminary interview information. The full-length oral history

goes into much greater depth and detail, and includes more reflection than

the preliminary interview.

This limited scope must be kept in mind in order to conduct an effective

preliminary interview. However, it should not limit your ability to engage in

the interview process with sensitivity and tact. It may be a challenge for both

interviewer and interviewee to discuss such difficult subject matter over the

telephone with a stranger. Thus, the preliminary interview requires knowl-

edge, delicacy, perception, and skill.

If you plan to conduct preliminary interviews with many people, we recom-

mend that you create a questionnaire. Questionnaires need not be strict; they

may contain a list of suggested questions from which the interviewer may

choose while conducting the preliminary interview. However, certain consistent

information should be gathered in the preliminary interview, such as the

interviewee’s date and place of birth, and a basic chronology of his or her

wartime locations. The Museum has created several questionnaires for vary-

ing inter

vie

w

ee experiences.

We have separate questionnaires for the

Holocaust survivor, witness, liberator, rescuer, and perpetrator. Although these

categories ar

e b

y no means perfect, they provide structure while allowing a

cer

tain degr

ee of flexibility in conducting pr

eliminar

y inter

vie

ws.

S

ee A

ppendix

1 for an example of our most-used questionnaire, the Survivor Questionnaire.

I

f y

ou plan to make the questionnaires available to researchers, be sure

to ask the inter

vie

w

ees for permission to use the information for r

esear

ch

purposes. Interviewees will most likely comply if you assure them that their

addr

esses and telephone numbers will not be released to researchers without

their consent.

ORAL HIS

T

OR

Y IN

TER

VIEW GUIDELINES

3

T

HE PRELIMINARY INTERVIEW

Providing

Options

f

or the

Interviewee

Conducting

the Preliminary

Interview

How Much

Detail?

Often the telephone maintains a distance between interviewer and interviewee

that makes it difficult to explore the heart of the interviewee’s story. If the

interviewee expresses discomfort in talking about certain experiences over the

telephone, the interviewer must respect that wish and accept the limitations

of interviewing by telephone. In such cases, it is wise to have a questionnaire

on hand to send to the interviewee.

However, getting a sense of how someone speaks is an important criterion

in determining whether or not to proceed with a full-length interview. The tele-

phone often is the only viable way to determine that. If an interviewee deems

the telephone inappropriate, you might suggest that the person write a basic

outline of his or her experiences or fill out a questionnaire, and ask

permission to call again afterward with a few follow-up questions.

Preliminary interviews also may be conducted in person. However, the

interviewer should make it clear that the preliminary interview is only intended

to gather information in preparation for an inter

view and that it is not an

in-depth recorded interview. This can be confusing for interviewees, who may

be more inclined to go into detail about their experiences in person than they

would over the telephone.

In the preliminary interview, find out the basic chronology of the

interviewee’s experiences, including dates and locations, so you will be able

to conduct thorough research and construct thoughtful questions for the

r

ecor

ded

inter

view.

One challenge of the preliminary interview is to create a balance between

being too concise and being too v

erbose. I

f it is necessary to err, err on the

side of including too much information rather than too little. M

or

e information

is always better than not enough because all further preparation and research

will be based on what is gather

ed at the preliminary interview (unless other

information exists, such as a memoir).

4 UNITED S

T

A

TES HOL

OCA

UST MEMORIAL MUSEUM

T

HE PRELIMINARY INTERVIEW

Assessing the

Preliminary

Interview

Summarizing

the Preliminary

Interview

Conduct the preliminary interview more than a week in advance of the

recorded interview (preferably several weeks in advance). Otherwise, you may

have the problem of the interviewee saying over and over again on tape, “As I

told you last week ....” Conducting the preliminary interview weeks in

advance of the recorded interview also will allow you time to call the inter-

viewee with additional questions, should any arise during the process of

preparing research for the interview.

When deciding whether or not to proceed with a full-length interview, it is

important to consider not only what the interviewee said, but how it was said.

This requires the interviewer to describe the preliminary interview, including

clarity of speech and memory; the ability to relate experiences in a coherent

narrative; and the ability to r

eflect upon and create a context for those expe-

riences.

See page 74 (Appendix 1) for a sample format of the preliminary

interview assessment.

The interviewer should write a summary of the preliminary interview soon

after it is conducted. The longer the interviewer postpones writing the sum-

mary, the more difficult it will be to remember how scattered notes fit together

into a narrative. Alternatively, we highly recommend that you invest in a

r

ecor

ding device that can be connected to y

our telephone.

You then can use

the recording to write the summary and use it for review purposes. However,

do not think of the r

ecor

ding as a substitute for the written summary, because

audiotapes ar

e mor

e difficult to r

evie

w than written summaries. Also, do not

consider the recording of the preliminary interview as an archival document

that can be kept in lieu of an in-person taped inter

vie

w. Tapes are expensive

and take up space, and it is time consuming to pr

eser

v

e them pr

operly

.

The quality of recorded telephone interviews will not be high enough to

warrant such time and expense.

See

Appendix 2 for a sample preliminary

interview summary

.

ORAL HIS

T

OR

Y IN

TER

VIEW GUIDELINES

5

T

HE PRELIMINARY INTERVIEW

Timing

of the

Preliminary

Interview

page 6 is blank

ORAL HIS

T

OR

Y IN

TER

VIEW GUIDELINES

7

Contacting

the

Interviewee

S

cheduling

the Interview

Chapter Overview

Contacting the Interviewee, 7

Scheduling the Interview, 7

Interview Note Taker, 8

Individuals Present at Interview, 8

Legal and Ethical Considerations, 8

Once you have determined who you would like to interview on tape, and

have a time frame in mind, contact the interviewee to see if he or she is will-

ing to be interviewed, and to offer more information about your project. Be

sure to let the interviewee know what is expected of him or her before the

interview takes place. For example, give an estimate of how long you expect

the interview to last, how the interview will be used once it is completed,

where the interview will take place, and who will be present at the interview.

Also explain that a release form must be signed, and give the inter

viewee a

sense of what is included in the form.

See “Legal and Ethical Considerations”

(page 8) for more information about release forms.

Being as informative as

possible can make interviewees feel more comfortable and in control of a

difficult process, about which they may feel quite vulnerable.

When scheduling the interview, be sure to allow plenty of time for conduct-

ing research and preparing for the interview. Many factors may necessitate

a lengthy preparation period, particularly if you have not conducted

Holocaust-related oral history interviews before. If this is the case, be sure to

review these Guidelines thoroughly before setting a date for the interview, so

you will have a good sense of the time required to prepare.

II. MAKING ARRANGEMENTS

FOR THE INTERVIEW

8 UNITED S

T

A

TES HOL

OCA

UST MEMORIAL MUSEUM

M

AKING ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE INTERVIEW

Interview

Note Taker

Individuals

Present at

Interview

Legal and

Ethical

Considerations

If you are conducting a video interview in a studio, there may be a greenroom,

where one can sit and watch the interview as it is being conducted. This is a

room, separate from the studio, with a TV monitor. In this scenario, someone

can take notes there as the interview transpires without distracting or dis-

turbing the interview. It is helpful to have the note taker write down the pho-

netic spellings of any personal names or obscure place names that are men-

tioned. The note taker then can confirm spellings before the interviewee

leaves the studio. This is important because some spellings are impossible to

confirm without the help of the interviewee. If you decide to have a note taker

at the interview, give that person plenty of advance notice.

If there is no greenroom or similar setup available, do not plan to have

a note taker in the same room where the interview is being conducted.

Instead, wait to confirm spellings until you have made a copy of the tape. In

this event, the person who takes notes will want to do so as soon as a copy of

the tape (or transcript) is available, so that he or she can call the inter

viewee

before too much time passes.

We generally recommend that few people as possible be present in the room

during the interview. The presence of an interviewee’s family member, while

comforting for the interviewee, may distract the interviewer or the interviewee.

However, handle this decision on a case-by-case basis, and make exceptions

for those who strongly prefer a family member to be present.

The O

ral H

istor

y Association has written principles and standar

ds for

conducting oral history interviews that detail the responsibility of any interview

pr

oject to its inter

viewees, the public, the profession, and sponsoring and

ar

chiv

al institutions. R

evie

w and follo

w these principles and standar

ds in the

conduct of any oral history project.

See Selected Bibliography (Appendix 5) for

mor

e information.

T

o obtain the right to use an inter

vie

w in y

our ar

chives or in any

production, each person you interview must sign a legal release form. This

form will determine who o

wns copyright of the interview and under what

terms or r

estrictions the copyright is o

wned. I

f no form is signed, copyright

of the interview will automatically belong jointly to the interviewer and the

interviewee. For more information on legal issues involved with conducting

oral history interviews, see

Oral History and the Law by John A. Neuen-

schwander.

See Appendix 5 for more information.

If you plan to donate an interview to an archive, you most likely will

be required to supply a signed release form along with the interview. The kind

of release form you create will depend on the goal of your interview collec-

tion. Several sample release forms can be found in the book

Doing Oral

History

by Donald A. Ritchie. See Appendix 5 for more information.

After you have confirmed a date for the interview, send the interviewee

a standard information sheet or letter that reiterates the basic arrangements

for the interview, including when and where it will take place, who will con-

duct it, how long you expect the session to last, etc. Enclose a copy of the

release form so the interviewee can review it carefully and ask any questions

before the inter

view. You should be very familiar with the release form, and

explain it carefully to the interviewee either before the interview or at the

interview. Ask the interviewee to bring the release form to the interview, but

be sure to bring an extra copy in case the interviewee forgets his or hers.

ORAL HIS

T

OR

Y IN

TER

VIEW GUIDELINES

9

M

AKING ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE INTERVIEW

page 10 blank

Chapter Overview

Set Aside Time for Research, 12

Review Interviewee’s Experiences, 13

Important Items to Research, 13

Things You Can Do at Home, 14

Visit a Library or Research Facility, 15

Maps, 16

Other Resources for Locating Places, 16

Expanding Your Search for Resources, 17

Using the Museum’s Resources, 17

If You Need Clarification, 19

Challenges, 19

Research List, 19

When to Stop, 20

You need not be an expert on the Holocaust to conduct a successful

interview. However, you must have knowledge and understanding of

the basic historical facts. The people you interview will expect this as

well. In addition, you must become knowledgeable about the particu-

lar circumstances of your interviewee’s history. The most important

ingredient for a successful interview is the preparation that you do

before the recorded interview. Even the most experienced interviewer

will spend hours preparing for an interview by reading historical material

ORAL HIS

T

OR

Y IN

TER

VIEW GUIDELINES

11

III. CONDUCTING RESEARCH

Set Aside

Time for

Research

relevant to the interviewee’s story and preparing questions based specif-

ically on that material. Preparation is critical.

There are thousands of books and articles about the Holocaust in

print. The Selected Bibliography (Appendix 5) includes what we consider

the most useful published sources. Once you have determined whom

you will interview, it is critical that you gather sufficient research materials

tailored to that person. The Oral History Branch has developed the fol-

lowing step-by-step guide to help make the process go smoothly.

Once you have the summary of the interviewee’s experiences in hand, begin

to do your research. Expect to depend on the help of a good local library,

Holocaust resource center, or other research facility to get this research done.

Plan to spend at least three to four hours gathering your research mate-

rials and four hours or more reading and preparing questions for each inter-

view you do. It is likely that for each interview, the total time spent on

research, reading, and preparing questions will be at least eight hours. When

you are doing research, try to be realistic about how many pages of reading

you will be able to do prior to the interview (some Holocaust resource centers

and libraries don’t allow patrons to check out books, so photocopying may be

necessary). Be selective and photocopy only the most relevant materials

(rather than

all possible r

elev

ant materials).

With four hours set aside for read-

ing and preparing questions, you should try to limit the research packet to

100 pages of photocopied materials. Even with 100 pages or less, there may

be some pages that you will read very closely and others that you will skim.

Of course, if you intend to spend more time reading, you will want to copy

more materials. The goal, however, is to collect the most suitable research for

the specific interviewee’s experiences, rather than indiscriminately photo-

copying every article or book on a certain topic.

12 UNITED S

T

A

TES HOL

OCA

UST MEMORIAL MUSEUM

C

ONDUCTING RESEARCH

Important

Items to

Research

Start by reviewing the preliminary interview questionnaire and the summary

that was based on the telephone interview and any other information in the

interviewee’s file. Take note of the people, places, events, and organizations

that you want to learn more about in preparation for the full-length interview.

We recommend that you jot down a one to two-page overview of the person’s

experiences, incorporating information from the questionnaire, the summary,

and other materials in the file. It can be helpful to write these notes in bullet

or outline fashion.

See Appendix 3 for a sample interviewee overview.

Read the following guidelines to get a sense of the questions you can ask your-

self as you review the information in the interviewee’s file and take notes on

the most important items to research.

Names of Interviewees

You may be able to find specific references in published sources about an

interviewee if that person or an immediate family member was well known or

had an unusual position—such as an administrator within the

Judenrat

(Jewish Council) at the Lodz ghetto—or was part of a small or select group,

such as an escapee of Treblinka or Auschwitz. Make a special note of the inter-

viewee’s name(s) during the war for doing this kind of research. Often, people

changed their names after the war when they immigrated to the United States

or other countries.

Names of People Mentioned by Interviewees

U

se the same considerations as abo

ve. Try to get more information about a

person with whom the inter

vie

w

ee had contact, especially if that person was

well known, had an unusual position, or was part of a small or select group

(for example, it could be someone no

w kno

wn to have been a protector or res-

cuer or perpetrator). Again, consider the possibility that someone could hav

e

different names (birth name, war name, postwar name, etc.).

P

laces

Whenever possible, research the place where the interviewee grew up as a

child.

Whether it was a large city or small village, some information usually

can be found in published sour

ces.

Then r

esear

ch other places to which the

ORAL HIS

T

OR

Y IN

TER

VIEW GUIDELINES

13

C

ONDUCTING RESEARCH

Review

Interviewee’s

E

xperiences

Things You

Can Do at

Home

interviewee went or was taken during the Holocaust/war and immediately

after (ghettos, camps, towns or cities where he or she might have hid,

displaced persons camps). Make a note of all places you wish to research.

Make it a priority to research those places where the interviewee may have had

memorable experiences and/or stayed for a considerable period of time.

Conversely, if the interviewee was taken to a camp for a half-day stopover and

did not have memorable experiences there, it would not be necessary to do

much research about that camp for the interview.

Events/Organizations

Do research on events that the interviewee experienced or witnessed, as well

as organizations and movements in which the interviewee participated. Do

enough research on events and organizations so that you are familiar with the

details and can visualize scenarios that the interviewee may discuss.

In most cases, y

ou will know which events and organizations to

research based on the information in the person’s file. However, as you read

about the places where the interviewee grew up and went thereafter, it is

important to be aware of the dates when the interviewee was in each place and

to be on the lookout for events that the interviewee may have experienced or

witnessed, even if the interviewee had not previously mentioned the events.

Often, if you are familiar with events that occurred in a particular place, you

can prepare more thoughtful and stimulating questions. This knowledge can

be especially important in cases where an interviewee forgot to mention

events when the preliminary interview was conducted.

Ther

e may be some pr

eliminar

y r

esear

ch that y

ou can do at home prior to

making a visit to a library or Holocaust resource center. First check any

H

olocaust-r

elated books that you may have in your home library for infor-

mation per

taining to the inter

vie

w

ee.

W

e have attached to these Guidelines a

Selected Bibliography (Appendix 5), consisting of what we consider some help-

ful r

esources on Holocaust history, Holocaust research, and oral history

methodology

.

This is b

y no means a compr

ehensiv

e bibliography, but it

should be helpful as a starting point. The text that we recommend most high-

ly on the histor

y of the Holocaust is

The D

estruction of the European Jews

(thr

ee v

olumes) b

y Raul H

ilberg.

You may be interested in purchasing some

14 UNITED S

T

A

TES HOL

OCA

UST MEMORIAL MUSEUM

C

ONDUCTING RESEARCH

Visit a

Library or

Researc

h

Facility

of the other books listed in the bibliography, but by no means will all of the

books listed be useful to you for each interview that you do. It is impossible

to buy enough books that deal with all the possible research topics in-depth,

so the sources you would have at home will most likely be helpful for the

preliminary, more general stages of research.

You may wish to write to various Holocaust resource centers or other

research facilities to learn if they have any information on the subjects of

interest to you. When writing to research facilities, be precise about the kind

of information you are seeking, and conscientious about any research facility’s

limited capacity for answering detailed research questions. Responses may be

slower than you expect. A list and contact information for Holocaust resource

centers can be found in the

Directory of the Association of Holocaust

Organizations,

which is updated annually. Copies of this directory may be

obtained by contacting the Holocaust Resource Center and Archives of the

Queensbor

ough Community College in Bayside, New York. The Museum

Web site houses the USHMM International Catalogue of audio and video

testimonies.

See “Research” on the Museum’s Web site.

Many research facilities’ holdings are now searchable on the Internet,

so a few keyword searches may yield positive results. If you have a computer

with access to the Internet and are able to visit the United States Holocaust

Memorial Museum to conduct your research, you can search the Museum’s

Library and Archives collections before your visit.

Eventually, you will need to visit a local library, Holocaust resource center, or

other r

esear

ch facility. Keep in mind that if you are working with a local

librar

y

, the selection of books may be limited, and y

ou might hav

e to obtain

the books you are looking for through an interlibrary loan. This can take

sev

eral w

eeks, so plan ahead.

I

f y

ou can visit the M

useum

’

s Librar

y and Archives, it is best to do so

on a weekday (except for national holidays) between 10 a.m. and 5 p.m.

because many mor

e resources are available then than on weekends. You may

use the Librar

y

’

s collection on-site only

. I

f you are interested in listening to

testimonies from the Museum’s collection of interviews, you may request

them fr

om the Reference Archivist. Refer to the Reference Archivist also for

access to unpublished documents in the Ar

chiv

es collection.

The P

hotographic

ORAL HIS

T

OR

Y IN

TER

VIEW GUIDELINES

15

C

ONDUCTING RESEARCH

Other

Resources

for Locating

Places

Reference Collection and Survivors Registry also are potential sources for rel-

evant information.

Begin your research by obtaining copies of maps that reflect the places where

the interviewee grew up and went during the Holocaust and immediate post-

war periods. Even if you are familiar with geography, it is best to treat each

interview as distinct and re-familiarize yourself with the specific locations of

the interviewee’s experiences. The goal is to become intimately aware of the

person’s path prior to, during, and immediately after the Holocaust. By high-

lighting the locations on maps, it is easier to obtain an understanding of the

distances covered from one place to the next. In general, maps provide a good

opportunity to visualize the interviewee’s experiences.

An excellent sour

ce for maps is the

National G

eographic Atlas of the

World.

You can make a copy of the maps of countries pertinent to the inter-

viewee, then highlight the relevant towns and cities on each map. Often if a

person went to several different countries, you will want to make a copy of

a map of Europe and highlight relevant place names on it, as well as on maps

of each country.

If you still need to identify the country in which a town is located, or

if it is difficult to find a town on a map, look up the place name in the atlas’

index. If you find the place name, turn to the appropriate page of the atlas

and use the coordinates listed in the index to locate the place on the map.

Then highlight it on y

our copy of that page.

If you do not find the place in the index of the atlas, there are other sources

to use. I

t always is key to consider that the place name may be spelled incor

-

r

ectly or that a name has changed o

v

er the y

ears and a differ

ent v

ersion is

more commonly accepted today.

Check the follo

wing additional sources when trying to locate a place

(to

wn, city

, ghetto, camp):

Columbia Lippincott Gazetteer

Das nationalsozialistische Lagersystem

(also known as the Arolsen

List—especially useful for identifying camps)

16 UNITED S

T

A

TES HOL

OCA

UST MEMORIAL MUSEUM

C

ONDUCTING RESEARCH

Maps

Expanding

Your Search

for Resources

Using the

Museum’s

Resources

Encyclopedia of the Holocaust

Encyclopaedia Judaica

The Ghetto Anthology

Historical Atlas of the Holocaust

Maps of specific countries (showing greater detail than the National

Geographic Atlas of the World)

Where Once We Walked

Yizkor Books (memorial books, mostly written in Yiddish or Hebrew)

See Selected Bibliography (Appendix 5) for more information on these sources and

a list of our other most-used published sources.

It usually is possible to find the place in one or more of these sour

ces.

There will be rare instances when a place is so obscure that it cannot be found.

In such cases, you should be able to get an idea of the town or city that is clos-

est to the place in question.

You may be able to fulfill a substantial amount of your research inquiries by

using our

Selected Bibliography (Appendix 5) of the published sources, espe-

cially if you are looking for information on a well-known topic such as

“Auschwitz,” “Lodz ghetto,” or “Dr. Mengele.” But you also will want to

check for relevant information in a library’s larger collection of books (and rel-

evant unpublished materials, if available). Additionally, many of the books

listed in our bibliography contain extensiv

e bibliographies of their o

wn.

The Museum will be a helpful resource for conducting interviews if you are

in the ar

ea and hav

e an opportunity to visit. The sections below provide

guidance on ho

w to use r

esour

ces in the M

useum

’s various divisions.

In addition, some of the Museum’s resources are searchable on the Internet.

The M

useum

’

s

W

eb site address is www.ushmm.org.

Once you are at the web site, select the option to search “Research”

which includes the Librar

y and Archives. In doing these searches, you will be

ORAL HIS

T

OR

Y IN

TER

VIEW GUIDELINES

17

C

ONDUCTING RESEARCH

able to get the call numbers for materials you are interested in reviewing when

you come to the Museum.

Library

If you have the opportunity to visit the Museum, you can use the Library’s

computer catalog to find specific books that are relevant to your research. If

you are using this system for the first time, ask the Reference Librarian for an

introduction to how it works. Even if you have used the system before, feel

free to ask for assistance.

With titles and call numbers written down, you can find the books on

the Library’s shelves. If you cannot locate a book, ask the Reference Librarian

for help (occasionally a book is waiting to be shelved or has been mis-shelved).

Begin your search for information with the book’s table of contents.

Next, check the index (if one exists). Also, refer to the book’s bibliography for

more sour

ces. Often, information can be found simply by flipping through

the pages of a book. There will be times when you will not find relevant infor-

mation in a book, even though its title gave you the impression that it would

be helpful. Similarly, a book that didn’t appear useful by its title may have

relevant information. Thus, it is good to be on the lookout for books other

than the one you are trying to locate on the shelves, since books on the same

topic are shelved together. After you have removed a book and are finished

reviewing it, place it on the designated re-shelving carts. Do not re-shelve it. If

you obtained the book from the Reference Desk, return it to the desk.

We recommend that you wait until you have had the opportunity to

r

evie

w the Librar

y sour

ces you’ve gathered before making copies. By waiting

until you have reviewed most of your materials, you will have a better sense

of the most r

elev

ant pages to photocopy. When you have determined the

pages y

ou want to photocopy

, ask the R

efer

ence Librarian for assistance.

18 UNITED S

T

A

TES HOL

OCA

UST MEMORIAL MUSEUM

C

ONDUCTING RESEARCH

Archives

You may want to check the Archives for information, especially if you have

not found much material in the Library. There is a separate computer catalog

at the Museum that searches for the Archives’ holdings. Also, you would want

to search the Archives’ holdings if you think the interviewee may have donated

his or her unpublished writings.

Photographic Reference Collection

Occasionally, an interviewee will mention that he or she was photographed in

the ghettos or camps. There may be other times when you have reason to

believe there may be photographs of the interviewee from that time period. Go

to the Photographic Reference Collection to see if such photographs are at the

Museum. Also, check with them if you have not found much information on

a town, camp, or ghetto, but believe there may be photographs of the place.

As you are conducting your research, it may become apparent that you need

further clarification or elaboration on an aspect of the interviewee’s experi-

ences in order to effectively carry out your research. In this event, call the

interviewee directly and ask for a clarification, leaving enough time before the

interview to allow you to do more research if necessary.

Even with clarifying information from the interviewee, it may be difficult to

find r

elev

ant materials on certain topics, such as lesser-known towns, ghettos,

camps, etc. Consult with a H

olocaust r

esour

ce center when seeking

specialized information.

When y

ou have completed your research, it is helpful to write down a list of

the sour

ces y

ou hav

e compiled.

S

ee A

ppendix 4 for a sample r

esear

ch list.

Keep this list in the interviewee’s file; it may be useful to someone in the

futur

e (for example, if a follow-up interview is arranged).

ORAL HIS

T

OR

Y IN

TER

VIEW GUIDELINES

19

C

ONDUCTING RESEARCH

If You Need

Clarification

Researc

h

List

Challenges

When to

Stop

20 UNITED S

T

A

TES HOL

OCA

UST MEMORIAL MUSEUM

Ideally, after three to four hours of skimming materials and making

photocopies of items you want to read or review later, you will have compiled

a well-rounded research packet. In essence, the packet should represent

detailed information about the interviewee’s experiences (much of this

information would have been gathered in the preliminary interview) and the

larger historical context of the interviewee’s experiences. Review the section

“Important Items to Research” (page 13) and the overview you made based

on the preliminary interview to make sure you have covered the

important points.

Notes on

Preparing

Questions

Organizing

Questions

Chapter Overview

Notes on Preparing Questions, 21

Organizing Questions, 21

Using Questions in the Interview, 22

For every interview, it is essential to know about the interviewee’s

history so you can construct questions that directly relate to that person.

Use the research materials that you have gathered and a good chronology

of events as references in preparing questions. Additionally, you may

find some questions that are relevant to your interview in our list of

suggested questions.

You will be constructing questions from the time you have the preliminary

interview information in hand through the recorded interview itself.

Therefore, as you prepare your questions, it is important to consider how you

plan to conduct the interview and what direction you anticipate the interview

will take.

See Chapter VII, Conducting the Interview. Consider what kinds of

information you want to get from the interviewee and look for blank spots

and intriguing areas in the preliminary interview summary that you would

like to explore.

Some interviewers type up pages of questions prior to the interview, but then

put them aside befor

e they begin the actual inter

vie

w

, because looking at a list

of questions can be distracting fr

om listening to the inter

vie

w

ee.

This wor

ks

if you have an excellent memory and a great deal of experience conducting

ORAL HIS

T

OR

Y IN

TER

VIEW GUIDELINES

21

IV. PREPARING QUESTIONS

Using

Questions

in the

Interview

interviews. We recommend instead that you write down your questions, high-

lighting those you consider most important, so you can read them easily

during the interview.

Organize your questions chronologically, perhaps in phases, such as

“prewar life,” “Lodz ghetto,” “Auschwitz,” “liberation,” etc. In other words,

organize the questions according to the major episodes of the interviewee’s

experiences. Then, during the interview, hold your list of questions in your

lap, and only glance at it occasionally to be sure that important questions do

not go unanswered. You may wish to write your questions on several 4 x 6

index cards, which make little noise when handled during the interview.

Ideally, you will be familiar enough with your questions that you will need to

refer to them only occasionally, if at all, during the interview.

During the interview itself, do not plan to ask one question after another as

they are listed on the page. Often an interviewee will anticipate and answer

your questions, and there will be no need for you to ask them. If you are over-

ly concerned about having the interviewee answer your specific questions, you

will be distracted from what the interviewee is telling you. Therefore, even

though you have your questions written down, you should attempt to have

your most important questions in your mind, rather than depending on a

piece of paper. If you have a thorough sense of the events in the interviewee’s

life before you begin the interview, then the information that the interviewee

giv

es y

ou during the inter

vie

w should remind you of your questions. Allow

yourself to follow the interviewee’s lead and put your questions aside for parts

of the inter

vie

w. You may find that what the interviewee is telling you will

pr

ompt ne

w questions that y

ou had not ev

en consider

ed.

In any interview, focus on asking questions that invite reflection on the

par

t of the inter

viewee, rather than one-word responses. Generally avoid yes

or no questions. S

till, good questions do not hav

e to be complicated or flashy

.

One of the best sentences you can use during the interview to elicit details is,

“

Tell me more about that.”

22 UNITED S

T

A

TES HOL

OCA

UST MEMORIAL MUSEUM

P

REPAIRING QUESTIONS

Family/

Occupation/

Education

Chapter Overview

Family/Occupation/Education, 23

Religion and Politics, 24

Gender, 24

We have highlighted below a few thematic areas within the broad

spectrum of Holocaust experiences that you might consider weaving

into the interview. These are meant to be suggestive rather than exhaus-

tive, and some interviewees’ experiences may call for a different set of

thematic areas.

Once you are familiar with your interviewee’s experiences, con-

sider identifying certain themes that run through his or her life, and

create your own outline of themes. If you find that the themes outlined

below are applicable to your interviewee’s experiences, go to Chapter VI

for some suggested questions that relate to the themes you have outlined.

It is important to have some idea of the ways in which education (religious,

musical, scientific, etc.) play

ed a role in a person’s life. If one’s education

or background was not academic (for example, if the person were a trade or

skilled laborer), that factor may have provided opportunities that saved his

or her life. Knowing the situation in which someone was raised, including

home environment; relationship with parents, siblings, and friends; and the

parents’ occupations, can help us better understand the interviewee’s life.

ORAL HIS

T

OR

Y IN

TER

VIEW GUIDELINES

23

V. SUGGESTED THEMES

Religion and

Politics

Gender

The religious upbringing and beliefs, as well as the political views or activities

of the interviewee and the interviewee’s family and friends, are relevant to

understanding the interviewee’s choices and actions during the Holocaust.

When possible, it is helpful to get the interviewee to articulate this back-

ground. There even may be some connection between religious practice and

political activity that might lead you to deduce something about the connec-

tions between the environment in which a person was raised and his or her

later actions during Nazi persecution.

Gender is an area of investigation that is rather new to Holocaust studies as a

whole, and in the field of Holocaust oral history, it has generally been ignored

as a category. Nevertheless, it is essential to think through questions that relate

to gender. Some can be based on physiology, for example, questions about

menstruation, pregnancy, abortion, sexual relations, as well as sexual violence.

There also are questions that can be based on cultural and political

issues relating to positions of power held by men and women. For example,

positions on the

Judenrat (Jewish Council) were held exclusively by men, but

the councils sometimes had to make decisions that specifically affected

women. Nazi directives forbidding pregnancy forced the Jewish Councils to

make decisions concerning abortions. Decisions about those who would be

deported were sometimes made on the basis of gender. Explore how access to

jobs, food, and other resources differed for men and women. The similarities

in the liv

es of men and women also warrant exploration.

Other questions relating to gender can be based on the differences in

the ghettos, camps, and r

esistance gr

oups. As men and women were separated

in most camp situations, ask about differ

ences in ho

w the two genders r

elated

and organized. When men and women were together in ghettos or other

places, such as the C

z

ech family camp in Auschwitz, what sort of organization

was constr

ucted? Ask questions that elicit the str

uctur

e of daily life in the

camps—food distribution, sharing of food, days off, sanitation, barrack life,

wor

k assignments, roll call, friendships, brutality, etc. Such questions clearly

per

tain to men and women alike.

24 UNITED S

T

A

TES HOL

OCA

UST MEMORIAL MUSEUM

S

UGGESTED THEMES

Chapter Overview

Prewar Life, 26

The First Questions

Childhood Recollections

Nazi Rise to Power

Holocaust/Wartime Experiences, 28

Ghettos and Transit Camps

Labor Camps, Prisons,

Concentration/ Extermination Camps

Hiding/Passing and Escaping

Resistance

Postwar Experiences, 34

Liberation

Displaced Persons Camps

Emigration/Immigration

Beyond the War/Life After the Holocaust

Although we do not recommend that you use a standard questionnaire

for the interview, it is extremely helpful to be detailed about topics and

the kinds of questions you will construct in preparation for an inter-

view. No one should ask as many questions in one interview as we have

outlined in this chapter. Rather, these questions serve as a guide to the

level of detail we hope an interviewee will reveal. The questions also will

provide hints as to what you might ask if the interviewee does not go

into details about certain experiences.

ORAL HIS

T

OR

Y IN

TER

VIEW GUIDELINES

25

VI. SUGGESTED QUESTIONS

PREWAR

LIFE

When interviewing Holocaust survivors, the structure of the

recorded Holocaust testimony is typically divided into three sections:

prewar life, the Holocaust and wartime experiences, and postwar expe-

riences. Therefore, we have organized our suggested questions according

to these three broad categories. Questions for interviewees with other

Holocaust-related experiences, such as liberators, rescuers, bystanders, or

postwar relief agency workers, will require a different set of questions

than those outlined in this chapter. However, these questions may help

you create appropriate questions for other interviewee categories.

This section of the interview deals with the interviewee’s childhood and

upbringing—family life, friends, relationships, schooling, and prewar life in

general. Especially when speaking with survivors, this part of the interview

should demonstrate the kind of life and culture that was interrupted or

destroyed by National Socialism. It is important to get some sense of the per-

son’s interests and hobbies, along with the events that marked his or her life

prior to the Nazi rise to power or occupation. It also is important to draw out

the intervie

wee’s earliest recollections of the Nazis—especially what he or she

heard or read or experienced, such as the escalation of restrictions and legal

measur

es, and ho

w they affected family

, school, friends.

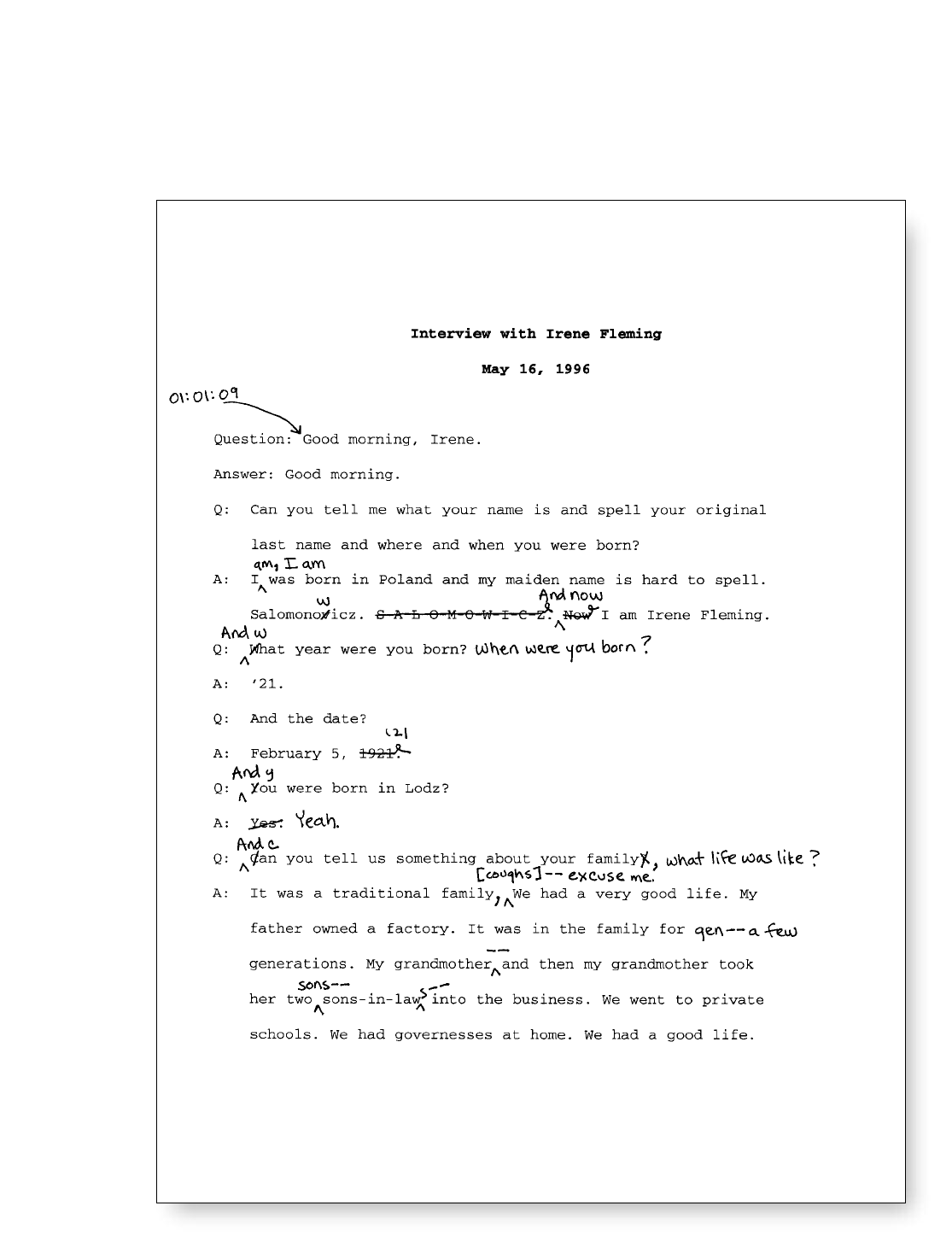

1. What was your name at birth? (Sometimes people have changed their

names, thus it is important to get this information at the outset.

Throughout the interview, when it is relevant, be sure to ask about nick-

names or other name changes, including changes at the time of liberation

and emigration.)

2. Where were you born?

3. What was your date of birth?

26 UNITED S

T

A

TES HOL

OCA

UST MEMORIAL MUSEUM

S

UGGESTED QUESTIONS

The Fir

st

Questions

1. Describe your family, including the role of your mother and father in

the household and their occupations. Describe your family life and your

daily life.

2. Describe school, friends, hobbies, affiliations with organizations.

3. Describe the nature of religious life in your family and community.

4. What were your family’s political affiliations?

5. What are your recollections of your city or town before the war, including

relationships between Jews and non-Jews? Any recollections of anti-

semitism or racism of any kind?

6. If the interviewee is older, ask him or her to describe job/occupation,

relationships, marriage, children.

1. What did you know about Hitler or Nazism? How was the Nazi rise to

power or Nazi policy understood in your family/community?

2. How did you become aware of the Nazi presence? Do you remember

the first day of occupation? Any recollections of seeing the Nazis?

Experiences? Feelings? Discussions? If you were a child, how did your

parents or other adults respond to the Nazi presence?

3. Describe recollections of escalation of Nazi power—How did the Nazi

presence change your life? Were you persecuted? Any plans or attempts

to leav

e?

4.

I

f in G

erman

y

—

Ask about the April 1933 boycott, book burnings,

Nuremberg race laws,

Kristallnacht (“Night of Broken Glass”), etc.

5. Elsewhere—Ask about the imposition of the Star of David on clothes,

J

e

ws prohibited from public places, confiscation or destruction of Jewish

pr

oper

ty

, for

ced labor

, movement out of homes.

6.

D

escribe ability or inability to r

un business or maintain occupation.

7.

I

f not J

e

wish, what did y

ou know about the circumstances of Jews?

Did you know any Jews? Did you try to help them?

ORAL HIS

T

OR

Y IN

TER

VIEW GUIDELINES

27

S

UGGESTED QUESTIONS

Childhood

Recollections

Nazi Rise

to Power

Ghet

tos

and Transit

Camps

It is essential to know about the particular ghetto, transit camp, labor camp,

prison, concentration or extermination camp where an interviewee was

interned. Specific questions must be constructed according to that interviewee’s

particular experiences.

There is no “typical” Holocaust experience, although there are some

categories of experiences into which many people fit. Alternately, there are

instances where one person’s experiences fit into multiple categories.

Most often, incarceration in a ghetto or transit camp preceded deportation to

labor, concentration, and/or extermination camps. Most Jews spent time in a

ghetto or transit camp; most non-Jews did not.

1. When and ho

w were you notified that you were to leave for the ghetto?

(For some people, a ghetto was formed where they already lived; conse-

quently, some of these questions may not be applicable.) How old were

you? How did you get to the ghetto? Was the “trip” organized? What did

you bring? What did you think about this “move?” What did you know?

What were your recollections of arrival at the new site? Describe your

first impressions. What did the ghetto look like? Was there a wall? If so,

what kind?

2. What are your recollections about getting adjusted? Were you alone?

Wher

e did you live? Where did you sleep? Did you sleep well? Did you

have dreams? Nightmares?

3.

What ar

e your recollections about living conditions—food, sanitation,

medical facilities, housing? D

escribe r

elationships among family members

and in the larger community. Describe daily life, including play and school

for childr

en. D

escribe social services—soup kitchens, hospitals, orphan-

ages, schools, facilities for the disabled. D

id y

ou hav

e any mobility or fr

ee

-

dom of movement? Was the ghetto closed at a certain time? What sort of

transpor

tation was there in the ghetto? Were there any non-Jews in the

ghetto? Any r

elationships betw

een J

e

ws and non-J

ews?

28 UNITED S

T

A

TES HOL

OCA

UST MEMORIAL MUSEUM

S

UGGESTED QUESTIONS

HOLOCAUST/

WARTIME

EXPERIENCES

4. If non-Jewish and in a ghetto, discuss your arrival, adjustment, living

circumstances, work, relations to Jews and to Nazi authorities.

5. What sort of work did you do? Did other family members work? How

did you get this “job?”

6. Describe any cultural, religious, or social activities—concerts, lectures,

parties, religious observances. What about friends and recreation? Were

intimate relationships important?

7. Did you hear any news of what was happening outside the ghetto? What

did you understand about your situation? About the situation of Jews?

Did you know about killings? Labor camps? Extermination camps? What

rumors were in the ghetto? What did you believe? Did you or anyone you

knew think of escaping or actually escape?

8. Were the lives of men and women similar or different? Different tasks?

Different positions in the community? Were men and women treated

differently? If so, how? Did you even notice that you were a man or a

woman? In other words, did gender matter to you? In what ways? What

about sexuality in the ghetto—relationships, menstruation, pregnancy,

abortions, prostitution, rape?

9. How did people around you treat each other?

10. Describe the structure of the ghetto—

Judenrat (Jewish Council), police,

work, food and clothing distribution, housing, medical care, etc.

E

v

aluate the wor

k of the

J

udenr

at

and J

e

wish police:

W

ere they corrupt?

Helpful? Trying to help in an impossible situation?

11. Were you involved in resistance activities? What did you do? Were you a

member of a gr

oup?

Was the group primarily men or both men and

women? R

oles? A

ctivities?

12.

What kept y

ou going? D

iscuss y

our motiv

ations and inspirations, if they

existed. Were you ever depressed? Did you ever not want to keep going?

D

escribe your situation.

13.

Describe the Nazi presence in your ghetto or transit camp. Give names of

G

ermans or collaborators if possible. D

escribe r

elationships or experiences.

ORAL HIS

T

OR

Y IN

TER

VIEW GUIDELINES

29

S

UGGESTED QUESTIONS

1. Describe deportation to camp—What were the circumstances of selec-

tion of those to be transported? Who did the selecting? Were you arrested?

Rounded up in selection? What was the method of transport?

Approximately how many people were transported? Conditions during

the trip? Any idea of the length of the trip? What were you told of the

purpose of the trip? Did you believe what you were told?

2. Describe your arrival and first impressions. Did you even know where

you were? With whom did you arrive? If with family, what happened?

What happened to your belongings? Describe any thoughts, feelings,

hopes, fears. What did you see, hear, smell? What was your condition on

arrival? Time of year? Time of day? Were there prisoners at your arrival

point? Describe any interactions. Describe your impressions of the camp

personnel.

3. Describe your registration into the camp—Shaving? Showers? Tattoo?