1

Sonia Livingstone ▪ Mariya Stoilova ▪ Rishita Nandagiri

December 2018

Children’s data and

privacy online

Growing up in a digital age

An evidence review

2

Table of contents

1. Executive summary ........................................................................................................................ 3

2. Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ 5

3. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 6

3.1. Context .................................................................................................................................... 6

3.2. Aims of the project and the evidence review ......................................................................... 8

4. Methodology .................................................................................................................................. 8

5. Children’s privacy online: key issues and findings from the systematic evidence mapping ..... 10

5.1. Conceptualising privacy in the digital age............................................................................. 10

5.2. Dimensions of children’s online privacy ............................................................................... 12

Interpersonal privacy .................................................................................................................... 13

Institutional privacy ...................................................................................................................... 13

Commercial privacy ....................................................................................................................... 14

Types of digital data ...................................................................................................................... 16

5.3. Privacy and child development ............................................................................................. 17

5.4. Children’s negotiation of privacy and information disclosure .............................................. 21

5.5. Children’s privacy protection strategies ............................................................................... 22

5.6. Media literacy ....................................................................................................................... 23

5.7. Differences among children .................................................................................................. 26

Socio-economic inequalities .......................................................................................................... 26

Gender differences ........................................................................................................................ 27

Vulnerability .................................................................................................................................. 28

5.8. Privacy-related risks of harm ................................................................................................ 28

5.9. Privacy protection and children’s autonomy ........................................................................ 30

5.10. Supporting children ........................................................................................................... 30

6. Recommendations ....................................................................................................................... 34

Appendices ........................................................................................................................................... 36

Appendix 1: Detailed methodology .................................................................................................. 36

Approach ....................................................................................................................................... 36

Search terms and outcomes ......................................................................................................... 36

Databases searched ...................................................................................................................... 38

Screening ....................................................................................................................................... 39

Coding ........................................................................................................................................... 40

Appendix 2: List of coded sources .................................................................................................... 41

Appendix 3: Glossary ........................................................................................................................ 48

References ............................................................................................................................................ 51

Cover image: Max Pixel

3

1. Executive summary

Children’s autonomy and dignity as actors in the

world depends on both their freedom to engage

and their freedom from undue persuasion or

influence. In a digital age in which many everyday

actions generate data – whether given by digital

actors, observable from digital traces, or inferred

by others, whether human or algorithmic – the

relation between privacy and data online is

becoming highly complex. This in turn sets a

significant media literacy challenge for children

(and their parents and teachers) as they try to

understand and engage critically with the digital

environment.

With growing concerns over children’s privacy and

the commercial uses of their data, it is vital that

children’s understandings of the digital

environment, their digital skills and their capacity

to consent are taken into account in designing

services, regulation and policy. Using systematic

evidence mapping, we reviewed the existing

knowledge on children’s data and privacy online,

identified research gaps and outlined areas of

potential policy and practice development.

Key findings include:

Children’s online activities are the focus of a

multitude of monitoring and data-generating

processes, yet the possible implications of this

‘datafication of children’

1

has only recently

caught the attention of governments,

researchers and privacy advocates.

Attempts to recognise children’s right to

privacy on its own terms are relatively new and

have been brought to the fore by the

adoption of the European General Data

Protection Regulation (GDPR, 2018) as well as

1

‘Datafication’ refers to the process of intensified

monitoring and data gathering in which people

(including children) are quantified and objectified –

positioned as objects (serving the interests of others)

rather than subjects (or agents of their own interests

and concerns); see Lupton, D. and Williamson, B. (2017)

The datafied child: The dataveillance of children and

implications for their rights. New Media & Society 19(5),

780-94.

by recent high-profile privacy issues and

infringements.

In order to capture the full complexity of

children’s privacy online, we distinguish

among: (i) interpersonal privacy (how my ‘data

self’ is created,

2

accessed and multiplied via

my online social connections); (ii) institutional

privacy (how public agencies like government,

educational and health institutions gather and

handle data about me); and (iii) commercial

privacy (how my personal data is harvested

and used for business and marketing

purposes).

The key privacy challenge (and paradox)

currently posed by the internet is the

simultaneous interconnectedness of voluntary

sharing of personal information online,

important for children’s agency, and the

attendant threats to their privacy, also

important for their safety. While children

value their privacy and engage in protective

strategies, they also greatly appreciate the

ability to engage online.

Individual privacy decisions and practices are

influenced by the social environment. Children

negotiate sharing or withholding of personal

information in a context in which networked

communication and sharing practices shape

their decisions and create the need to balance

privacy with the need for participation, self-

expression and belonging.

Institutionalised aspects of privacy, where

data control is delegated – voluntarily or not –

to external agencies such as government

institutions, is becoming the norm rather than

the exception in the digital age. Yet there are

gaps in our knowledge of how children

experience institutional privacy, raising

questions about informed consent and

children’s rights.

The invasive tactics used by marketers to

collect personal information from children

have aroused data privacy and security

concerns particularly relating to children’s

2

‘Data self’ refers to all the information available

(offline and online) about an individual.

4

ability to understand and consent to such

datafication and the need for parental

approval and supervision, especially for the

youngest internet users. While the

commercial use of children’s data is at the

forefront of current privacy debates, the

empirical evidence related to children’s

experiences, awareness and competence

regarding privacy online lags behind. The

available evidence suggests that commercial

privacy is the area where children are least

able to comprehend and manage on their

own.

Privacy is vital for child development – key

privacy-related media literacy skills are closely

associated with a range of child

developmental areas. While children develop

their privacy-related awareness, literacy and

needs as they grow older, even the oldest

children struggle to comprehend the full

complexity of internet data flows and some

aspects of data commercialisation. The child

development evidence related to privacy is

insufficient but it undoubtedly points to the

need for a tailored approach which

acknowledges developments and individual

differences amongst children.

Not all children are equally able to navigate

the digital environment safely, taking

advantage of the existing opportunities while

avoiding or mitigating privacy risks. The

evidence mapping demonstrates that

differences among children (developmental,

socio-economic, skill-related, gender- or

vulnerability-based) might influence their

engagement with privacy online, although

more evidence is needed regarding the

consequences of differences among children.

This raises pressing questions for media

literacy research and educational provision. It

also invites greater attention to children’s

voices and their heterogeneous experiences,

competencies and capacities.

Privacy concerns have intensified with the

introduction of digital technologies and the

internet due to their capacity to compile large

datasets with dossiers of granular personal

information about online users. Children are

perceived as more vulnerable than adults to

privacy online threats due to their lack of

digital skills or awareness of privacy risks.

While issues such as online sexual exploitation

and contact with strangers are prominent in

current debates, more research is needed to

explore potential links between privacy risks

and harmful consequences for children,

particularly in relation to longer-term effects.

No longer about discipline and control alone,

surveillance now contains facets of ‘care’ and

‘safety’, and is promoted as a reflection of

responsible and caring parents and is thus

normalised. Risk aversion, however, restricts

children’s play, development and agency, and

constrains their exploration of physical, social

and virtual worlds.

While the task of balancing children’s

independence and protection is challenging,

evidence suggests that good support can make

an important difference to children’s privacy

online. Restrictive parenting has a suppressive

effect, reducing privacy and other risks but

also impeding the benefits of internet use.

Enabling mediation, on the other hand, is

more empowering in allowing children to

engage with social networks, albeit also

experiencing some risk while learning

independent protective behaviours.

While the evidence puts parental enabling

mediation at the centre of effective

improvement of children’s privacy online,

platform and app features often prompt

parental control via monitoring or restriction

rather than active mediation. Media literacy

resources and training for parents, educators

and child support workers should be

considered as the evidence suggests

important gaps in adults’ knowledge of risks

and protective strategies regarding children’s

data and privacy online.

The evidence also suggests that design

standards and regulatory frameworks are

needed which account for children’s overall

privacy needs across age groups, and pay

particular attention and consideration to the

knowledge, abilities, skills and vulnerabilities

of younger users.

5

2. Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) for funding this project. In particular, we

would like to thank the team – Robert McCombe, Lisa Atkinson, Adam Stevens, Lisa O’Brien and Rachel

Bennett – for their support.

We are thankful to our expert advisory group members for sharing valuable recommendations:

Jonathan Baggaley (PSHE Association)

Dr Ayelet Blecher-Prigat (Academic

College for Law and Science)

Dr Leanne Bowler (Pratt Institute)

Dr Monica Bulger (Future of Privacy Forum

and Data & Society Research Institute)

John Carr, OBE (Children’s Charities’

Coalition on Internet Safety)

Professor Nick Couldry (Department of

Media and Communications, LSE)

Jutta Croll (Stiftung Digitale Chancen)

Julie de Bailliencourt (Facebook)

Anna Fielder (Privacy International)

Kerry Gallagher (ConnectSafely.org)

Patrick Geary (UNICEF)

Emily Keaney (Office of Communications)

Louis Knight-Webb (Who Targets Me)

Professor Eva Lievens (Law Faculty, Ghent

University)

Claire Lilley (Google)

Dr Orla Lynskey (LSE Law)

Louise Macdonald (Young Scot)

Alice Miles (Office of the Children’s

Commissioner)

Andrea Millwood-Hargrave (International

Institute of Communications)

Dr Kathryn Montgomery (School of

Communication, American University)

Dr Victoria Nash (Oxford Internet Institute)

Dr Elvia Perez Vallejos (University of

Nottingham)

Jen Persson (DefendDigitalMe)

Joseph Savirimuthu (University of

Liverpool)

Vicki Shotbolt (Parent Zone)

Professor Elisabeth Staksrud (University of

Oslo)

Dr Amanda Third (University of Western

Sydney)

Josie Verghese (BBC School Report)

Dr Pamela Wisniewski (University of

Central Florida

We also thank the LSE Research Division and James Deeley at the LSE Department of Media and

Communications for their ongoing project support and assistance, and Heather Dawson at the British Library

of Political and Economic Science for her expert suggestions and guidance with relevant databases and

sources.

6

3. Introduction

3.1. Context

The nature of privacy is increasingly under scrutiny

in the digital age, as the technologies that mediate

communication and information of all kinds become

more sophisticated, globally networked and

commercially valuable. The conditions under which

privacy can be sustained are shifting, as are the

boundaries between public and private domains

more generally. In public discourse, widely

expressed in the mass and social media, there is a

rising tide of concern about people’s loss of control

over their personal information, their understanding

of what is public or private in digital environments

and the host of infringements of privacy resulting

from the actions (deliberate or unintended) of both

individuals and organisations (especially state and

private sector), as well as from hostile or criminal

activities.

Our focus is on privacy both as a fundamental

human right vital to personal autonomy and dignity

and as the means of enabling all the activities and

structures of a democratic society. Within this, it is

the transformation in the conditions of privacy

wrought by the developments of the digital age that

occupy our attention in this report. These centre on

the creation of data – which can be recorded,

tracked, aggregated, analysed (via algorithms and

increasingly, via artificial intelligence) and

‘monetised’ – from the myriad forms of human

communication and activity which, throughout

history, have gone largely unrecorded, being

generally unnoticed and quickly forgotten.

The transformation of ever more human activities

into data means that privacy (rather than publicity)

now requires a deliberate effort, that it is far easier

to preserve than remove the record of what has

been said or done, that surveillance by states and

companies is fast becoming the norm not the

exception, and that our data self (or ‘digital

footprint’) represents not merely a shadow of our

‘real’ self but rather, a real means by which our

options become determined for us by others,

according to their (rather than, or at best, as well as

our own) interests.

The position of children’s privacy in the digital

environment is proving particularly fraught for three

main reasons. First, children are often the pioneers

in exploring and experimenting with new digital

devices, services and contents – they are, in effect,

the canary in the coal mine for wider society,

encountering the risks before many adults become

aware of them or are able to develop strategies to

mitigate them. Although children have always been

experimental, even transgressive, today these

actions are particularly consequential, because

children now act on digital platforms that both

record everything and, being often proprietary, own

the resulting data traces (Montgomery, 2015). The

growing ‘monetisation’, ‘dataveillance’,

‘datafication’ and sometimes misuse or ‘hacking’ of

children’s data, and thereby privacy, is occasioning

considerable concern in public and policy circles.

While it is often children’s transgressive or ‘risky

opportunities’ (Livingstone, 2008) that draw

attention to the added complexities of the digital

environment, these raise a more general point. In

the digital age, actions intended by individuals to be

either private (personal or interpersonal) or public

(oriented to others, of wide interest, a matter of

community or civic participation) in nature now take

place on digital networks owned by the private

sector, thereby introducing commercial interests

into spheres where they were, throughout history,

largely absent (Livingstone, 2005).

Second, despite their facility with and enthusiasm

for all things digital, children have less critical

understanding of present and future risks to their

wellbeing posed by the use of the digital

environment than many adults. Most research

attention has concentrated on teenagers, but

increasingly the very youngest children are

becoming regular uses of the internet (Chaudron et

al., 2018). So, too, are those who are ‘at risk’ or in

some ways vulnerable as regards their mental or

physical health or their socio-economic or family

circumstances. This raises new challenges regarding

the demands on children’s media literacy (especially

its critical dimensions) as well as that of the general

public (including parents and teachers). Meeting

these challenges inclusively and at scale is generally

seen as the remit of educators, yet the task may be

too great, insofar as understanding the complexities

of digital data processes and markets is proving

beyond the wit of most adults.

Third, children’s specific needs and rights are too

little recognised or provided for by the design of the

digital environment and the regulatory, state and

commercial organisations that underpin it

7

(Livingstone et al., 2015). Here there are growing

calls for regulatory intervention, again on behalf of

children and also the general public, including for

mechanisms even to know who is a child online and

for privacy-by-design (along with safety- and ethics-

by-design) to become embedded in the digital

environment, so that children’s specific rights and

needs – including regarding their personal data – are

protected (Kidron et al., 2018). The recent

Recommendation from the Council of Europe (2018)

on guidelines to protect, respect and fulfil the rights

of children in the digital environment offers a

comprehensive framework, and something of a

moral compass for states, as they seek to address

the full range of children’s rights specifically in

relation to the internet and related digital

technologies. Within this, privacy and data

protection are rightly prominent.

In Europe, 2018 saw the implementation of wide-

ranging new legislation in the form of the General

Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), incorporated

into UK law by the Data Protection Act 2018. This

recognises that ‘personal data protection is a

fundamental right in the EU’ (Jourová, 2018) and

seeks to return a measure of control to the

individual (or internet user) regarding their privacy

online. In a series of policy documents, the UK’s data

protection authority, the Information

Commissioner’s Office (ICO), explains the

implications of the GDPR for UK citizens in general

and for children in particular.

3

As regards the latter,

Recital 38 of the GDPR sets out the imperative for

regulatory provision to protect children’s data:

Children merit specific protection with regard

to their personal data, as they may be less

aware of the risks, consequences and

safeguards concerned and their rights in

relation to the processing of personal data.

Such specific protection should, in particular,

apply to the use of personal data of children for

the purposes of marketing or creating

personality or user profiles and the collection of

personal data with regard to children when

using services offered directly to a child.

3

For details, see Children and the GDPR

(https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/guide-to-the-

general-data-protection-regulation-gdpr/children-and-

the-gdpr/) and Guide to the General Data Protection

Regulation (https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/guide-

to-the-general-data-protection-regulation-gdpr/).

The ICO recently held a consultation

4

on how such

protection can and should be achieved for children

and a number of pressing challenges are already

becoming apparent (Livingstone, 2018). In this

review, our concern is less with the specifics of

regulation and more with the conditions under

which children use the internet, the implications of

their activities (and those of others) for the personal

data that is collected and analysed about them and

especially, how children themselves understand and

form views regarding their privacy, the uses of their

data and the implications for their engagement with

the digital environment – all part of their media

literacy. GDPR Recital 38 makes clear reference to

children’s vulnerabilities, their awareness of online

risks and the adverse consequences to their privacy

that regulation should seek to prevent.

However, throughout the consultations and

deliberations during the long build-up to the GDPR,

children’s views were barely included, and research

with or about children was little commissioned or

considered. Nonetheless, the GDPR builds on a

series of assumptions regarding the maturity of

children (to give their consent) and the role of

parents (in requiring their consent for the use of

data from under-age children), most notably in

relation to GDPR Article 8.

5

It also presumes

knowledge of how children can understand the

Terms and Conditions of the services they use (in

requiring that these be comprehensible to services

users), the risks that face children (in the

requirement for risk impact assessments) and more.

Hence our primary question – what do children

understand and think about their privacy and use of

personal data in relation to digital, especially

commercial, environments?

4

See Call for evidence – Age-appropriate design code

(https://ico.org.uk/about-the-ico/ico-and-stakeholder-

consultations/call-for-evidence-age-appropriate-design-

code/).

5

Parental consent is required for underage children only

when data is processed on the basis of consent (rather

than another basis for processing, such as contract, legal

obligation, vital interests, public task or legitimate

interests). For more details see: https://ico.org.uk/for-

organisations/guide-to-data-protection/guide-to-the-

general-data-protection-regulation-gdpr/lawful-basis-

for-processing/

8

3.2. Aims of the project and the evidence

review

With growing concerns over children’s privacy online

and the commercial uses of their data, it is vital that

children’s understandings of the digital

environment, their digital skills and their capacity to

consent are taken into account in designing services,

regulation and policy. Our project Children's data

and privacy online: growing up in a digital age seeks

to address questions and evidence gaps concerning

children’s conception of privacy online, their

capacity to consent, their functional skills (e.g., in

understanding terms and conditions or managing

privacy settings online) and their deeper critical

understanding of the online environment, including

both its interpersonal and especially, its commercial,

dimensions (its business models, uses of data and

algorithms, forms of redress, commercial interests,

and systems of trust and governance). The project

also explores how responsibilities should be

apportioned among relevant stakeholders and the

implications for children’s wellbeing and rights.

The project takes a child-centred approach, arguing

that only thus can researchers provide the needed

integration of children’s understandings, online

affordances, resulting experiences and wellbeing

outcomes (Livingstone and Blum-Ross, 2017).

Methodologically, the project prioritises children’s

own voices and experiences within the wider

framework of evidence-based policy development

by conducting focus group research with children of

secondary school age, their parents and educators,

from selected schools around the country;

organising child deliberation panels for formulating

child-inclusive policy and educational/awareness-

raising recommendations; and creating an online

toolkit to support and promote children’s digital

privacy skills and awareness.

Given current regulatory decisions regarding

children’s awareness of and capacity to manage

digital risks and their consequences for their

wellbeing – manifest in policies for privacy-by-

design, child protection, child and parent consent,

minimum age for use of services, and so forth – the

project focuses on children aged 11 to 16

(Livingstone, 2014; Kidron and Rudkin, 2017;

Macenaite, 2017; UNICEF, 2018).

The aim of the evidence review is to gather,

systematise and evaluate the existing evidence base

on children’s privacy online, particularly focusing on

key approaches to the study of children’s privacy in

the digital environment; children’s own

understandings, experiences and views of privacy

online; their approach to navigating the internet and

its commercial practices; their experiences of online

risks and harm; ways of supporting children’s privacy

and media literacy; and how differences in age,

development and vulnerability make a difference.

4. Methodology

The research questions guiding the review are:

How do children understand, value and

negotiate their privacy online?

What are the digital skills, capabilities or

vulnerabilities with which children approach

the digital environment?

What are the significant gaps in knowledge

about children’s online privacy and

commercial use of data?

We conducted a systematic mapping of the evidence

(Grant and Booth, 2009; Gough et al., 2012; EPPI-

Centre, 2018), utilising a comprehensive and

methodical search strategy, allowing us to include a

broad range of sources including policy

recommendations, case studies and advocacy

guides. Here we summarise our methodology

briefly. For a detailed account of the methodology,

including search terms, databases, inclusion criteria

and screening and coding protocols, see Appendix 1.

Three groups of search terms were combined, to

identify research about children, privacy and the

digital environment (primarily the internet, but

including all digital devices, content and services

that can be connected to it). This demanded a

particularly multidisciplinary approach to the

research framing and interpretation of results.

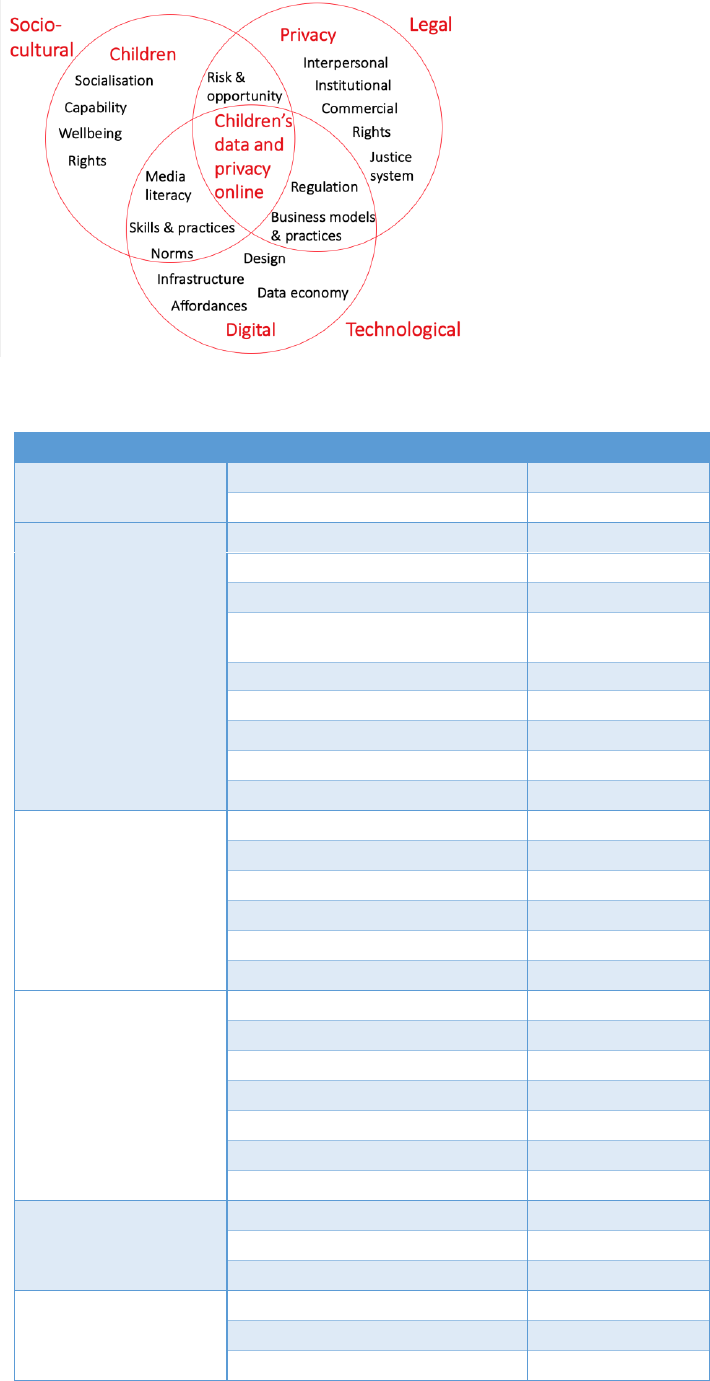

We identified three disciplines relevant to the scope

of the review – social and cultural studies, legal and

regulatory studies, and technological/computer

sciences (see Figure 1), with databases and search

terms (children, privacy, digital) chosen to match

these three areas. This review focuses on the

overlap between the three areas, centring on the

privacy and data literacy of children.

9

Figure 1: Concept mapping of three disciplines and their overlaps

Table 1: Results by category

Category

Type

Number of studies

Type of study

(n = 105)

Primary research

99

Secondary data analysis

6

Methodology

(n = 105)

Survey

33

Mixed-methods

20

Interviews

15

Experimental or quasi-

experimental

10

Participatory

8

Secondary analysis

6

Focus group discussions

5

Observational

4

Other

4

Age

(coded across multiple

categories)

Age 0-3

2

Age 4-7

10

Age 8-11

46

Age 12-15

77

Age 16-19

64

Could not categorise

3

Study focus

(coded across multiple

categories)

Behaviours and practices

67

Attitudes and beliefs

50

Media literacy and understandings

37

Privacy strategies of the child

27

Support and guidance from others

9

Design and interface (affordances)

5

Decision-making to use services

2

Type of privacy

(coded across multiple

categories)

Interpersonal

86

Commercial

37

Institutional

8

Data type

(coded across multiple

categories)

Data given

93

Data traces

27

Inferred data

7

10

The systematic evidence mapping included an

extensive search of 19 databases that covered the

social sciences, legal studies and computer science

disciplines, resulting in 9,119 search items. We

consulted our expert advisory group for additional

relevant literature, adding 279 more items to our

review. This gave us a total of 9,398 search results.

We screened these results for duplicates and

relevance, leaving a total of 6,309 relevant results.

Using a predefined inclusion criteria and a two-

phase process, we narrowed the results to a final

sample of 105 studies (see Table 1 above and the

Report Supplement for a summary of each source).

We limited the resulting sources to empirical

research studies with children, including both

primary and secondary data analysis studies.

Summaries of these studies can be found in the

Report supplement.

The primary research studies draw more on

quantitative than qualitative methodologies, with a

significant number using mixed-methods

approaches. We also categorised the empirical

studies by age, study focus and the types of privacy

and data investigated. Studies tend to focus on

children across different age groups, with a majority

of them focusing on 12- to 19-year-olds. There is a

dearth of research on 0- to 7-year-olds, and to a

lesser but still significant extent for 8- to 11-year-

olds. The studies focus predominantly on the

behaviours and practices of young people, as well as

on their attitudes and beliefs. We also categorised

the types of privacy explored in our sample, finding

that interpersonal privacy is, by far, the most

frequently addressed. This is also reflected in the

types of data investigated in our sample, where data

given is the most common type of data explored.

In what follows we begin with a conceptual analysis

of privacy in the digital age, moving, then, to

empirical findings regarding children’s

understanding of privacy in relation to digital and

non-digital environments.

5. Children’s privacy online: key issues and findings from the systematic

evidence mapping

We first explore the key areas related to children’s

privacy online which we identified during the

systematic evidence mapping, starting with how

privacy has been conceptualised in relation to the

digital environment, the key dimensions that

constitute child privacy and the types of data

involved, and the links between privacy and child

development. We then focus on how children

manage (and negotiate) their privacy online and the

protection strategies they employ. We also consider

how differences among children might put some

children in particularly vulnerable situations, and

review the privacy-related risks and harm that

children face. Finally, we review the evidence on

privacy protection, children’s autonomy and best

approaches to supporting children’s privacy online.

5.1. Conceptualising privacy in the digital age

Definitions of privacy can be difficult to apply in the

digital environment, as are efforts to measure

privacy empirically (Solove, 2008). From Westin

(1967: 7) we find the classic conceptualisation of

privacy: ‘the claim of individuals, groups, or

institutions to determine themselves when, how and

to what extent information about them is

communicated to others’. The tensions Westin

identified between privacy, autonomy and

surveillance apply strongly in the contemporary

digital environment, even though his work was

written much earlier. Recent theoretical approaches

also tend to define privacy online in terms of

individual control over information disclosure and

visibility (Ghosh et al., 2018), but they seek ways of

acknowledging how this control depends on the

nature of the social and/or digital environment.

Thus contextual considerations are increasingly

important in discussions of privacy. Nissenbaum’s

(2004) theory of privacy as contextual integrity

refers to the negotiation of privacy norms and

cultures. For her, information sharing occurs in the

context of politics, convention and cultural

expectations, guided by norms of appropriateness,

distribution of information and violation. Hence

these norms must be examined and taken into

account when making judgements about privacy and

privacy-related actions.

11

Another approach, communication privacy

management theory, focuses on the relational

context, framing privacy as a process of boundary

negotiation within specific interpersonal

relationships. Thus privacy emerges from (or is

infringed by) the negotiation over the social rules

over what information is shared, when and with

whom, and how these rules are agreed with others

(Petronio, 2002). Increasingly it is argued that

privacy is better understood in relational rather than

in individual terms (Solove, 2015; Hargreaves, 2017).

Rather than focusing on an individual’s intent to

control their information, it can be more productive

to understand how privacy-related actions – for

instance, to keep or tell a secret, to disclose

sensitive information to others, to collaborate with

others to establish social norms for information

sharing – depend on and are meaningful within the

specific relationships (and their contexts, norms and

boundaries) to which individuals are party. These

actions are embedded in a context of norms, legal

and policy regulations, and rights (O'Hara, 2016).

To conceptualise privacy in the digital age, we start

by observing how the nature of the digital

environment adds complexity to the social

environment, especially with the widespread

adoption of social media. boyd and Marwick (2011)

use the notion of networked privacy to refer to the

public-by-default nature of personal

communications in the digital era, thus affecting the

decisions of individuals about what information to

share or withhold. They outline four key affordances

(or socially designed features of the digital

environment) of networked technologies:

persistence, replicability, scalability and

searchability. These affordances mean that people

must contend with dynamics not usually

encountered in daily life before, over and above the

established demands of social interaction. These

include the imagined audience for online

posts/performances, the collapse and collision of

social contexts, the blurring of public and private

spheres of activity, and the nature of network

effects (notably, the ways in which messages spread

within and across networks).

One consequence is that where social interactions

used to be private-by-default, they are increasingly

becoming public-by-default, with privacy achieved

‘through effort’ rather than something to be taken

for granted. Another is that where social

interactions used to be typically (although not

necessarily) ephemeral, they are increasingly

digitally recorded through digital traces that are

themselves amenable to further processing and

analysis, whether for individual or organisational

(public or commercial) benefit. Yet another is that,

because of the affordances of online environments

(including the conditions of identifiability or

anonymity, as well as the effects of particular

regulation or design), people tend to act differently

online than offline.

Studies suggest that the mediated nature of social

network communication facilitates greater self-

disclosure of personal information than face-to-face

interaction (Xie and Kang, 2015). The importance of

online self-representation and identity experiments

to youthful peer cultures also fuels online sharing of

personal information. In these contexts teenagers

may prioritise what to protect more than what to

disclose, with exclusions carefully considered (boyd

and Marwick, 2011). Steeves and Regan (2014)

identify four different understandings of the value of

privacy by young people: contextual, relational,

performative and dialectical. Contextual

understandings relate to how privacy is guided by

certain norms and values, often complicated by

evolving environment and disagreements with what

these norms are, especially with adults. Relational

understandings associate privacy with forming

relationships which need to be based on

transparency, mutuality and trust, but some online

relationships that young people have (with school

boards, marketers, potential employers or law

enforcement agencies) are one-dimensional,

Steeves and Regan (2014) suggest.

In such a context, the idea of consenting to online

privacy terms and conditions does not involve

reciprocity; it forms a one-way relationship allowing

the monitoring of the consent-giver who has no

other option but to agree or be refused the benefit.

These one-way relationships are purely

instrumental, do not involve a process of

negotiation, and jeopardise autonomy when the

online environment allows the instrumental and

commercial invasion of privacy. Finally, dialectical

understanding of privacy points to the tension

between the public and the private spheres which

have collapsed online, which means that young

people can seek both privacy and publicity online at

the same time necessitating the constant

negotiation of privacy and consent which cannot be

given away irreversibly (Steeves and Regan, 2014).

12

So, while the dynamics of the online context can

threaten and potentially violate privacy, children

also experience its affordances as supporting their

identity, expressive and relational needs by

enhancing their choice and control over personal

information and thus, their privacy online (Vickery,

2017). Online spaces, while technically public, can be

experienced as offering greater ‘privacy’ because

they are parent-free compared with, for example,

what a child can say or do at home (boyd and

Marwick, 2011). Hence, while children, like anyone

else, are influenced by social as well as digital

environments, their privacy perceptions and

practices might be different from how adults

(parents, educators, policy-makers) envision them or

wish them to be. For example, a 13-year-old girl

participating in the ethnographic study of London-

based schoolchildren by Livingstone and Sefton-

Green (2016) explained that she considered

Facebook to be public and Twitter private, because

her cohort’s social norms dictated that they were all

on Facebook, making any posting visible to everyone

she knew (even though her profile was set to

private), whereas few of her friends used Twitter so

she could have a conversation there which was

visible only to a select few.

Similarly, a study of Finish children aged 13 to 16

creating own online blogs expereinced them as

intimate spaces affording welcome opportunities for

making new connections, rather than spaces where

information is shared publicly (Oolo and Siibak,

2013). A final example is the study of a youth online

platofrm for anonymous sharing of experiences of

online hurtful behaviour (MTV Over the Line) by

Zizek (2017), who describes that communicating

with strangers in this context carries trust and

closeness – characteristics that are usually ascribed

to children’s relationships with family or friends. This

shifts privacy from traditionally shared in non-public

circles to being shared in a public space – creating a

new way of dealing with what is seen as public and

private (Zizek, 2017). This means that one cannot

simply determine contextual norms from a formal

knowledge of the digital environment but rather,

empirical research including the views and

experiences of children is vital.

5.2. Dimensions of children’s online privacy

In this review, we follow Nissenbaum’s definition of

privacy as ‘neither a right to secrecy nor a right to

control, but a right to appropriate flow of personal

information’ (Nissenbaum, 2010: 3). This embeds

the notion of privacy as relational and contextual

(relationships being a specific, and crucial, part of

any social context) in the emphasis on ‘appropriate’

(as judged by whom? Or negotiated how?) and

‘flow’ (from whom to whom or what?).That is, it

does not assert the right to control as solely held by

the individual but rather, construes it as a matter of

negotiation by participants. But what kinds of

relationships, in what kinds of context, and as part of

what power imbalances are pertinent for children’s

privacy in the digital age?

A recent UNICEF report on children’s privacy online

and freedom of expression distinguishes several

dimensions of privacy affected by digital

technologies – physical, communication,

informational and decisional privacy (UNICEF, 2018).

Physical privacy is violated in situations where the

use of tracking, monitoring or live broadcasting

technologies can reveal a child’s image, activities or

location. Threats to communication privacy relate to

access to posts, chats and messages by unintended

recipients. Violation of information privacy can occur

with the collection, storage and processing of

children’s personal data, especially if this occurs

without their understanding or consent. Finally,

disruptions of decisional privacy are associated with

the restriction of access to useful information which

can limit children’s independent decision-making or

development capacities (UNICEF, 2018).

Consequently, the report pays particular attention

to children’s right to privacy and protection of

personal data, the right to freedom of expression

and access to information diversity, the right to

freedom from reputational attacks, the right to

protection attuned to their development and

evolving capacities and the right to access remedies

for violations and abuses of their rights – as

specified in the UN Convention on the Rights of the

Child (1989).

Such attempts to recognise children’s right to

privacy on its own terms are relatively new and have

been brought to the fore by the recent more

comprehensive focus on privacy (and its violations)

in the light of the discussions prompted by the

adoption of the GDPR across Europe. Until then, the

privacy discourse tended to be developed mainly in

relation to adults’ privacy, undervaluing the privacy

of children, and also tended to see children’s privacy

as managed by responsible adults (like family

members) who had children’s best interests at heart

13

(Shmueli and Blecher-Prigat, 2011).

6

For our

systematic mapping of the current debate and

emerging research regarding children’s privacy

online, its dimensions and relevant actors, we find

the distinction between interpersonal, institutional

and commercial privacy helpful. This means that,

while we have the questions of rights firmly in mind

(UNICEF, 2018), to grasp the import of the available

empirical research we focus more pragmatically on

the nature of the relationships and contexts in which

children act in digital environments and on how they

understand the implications for their privacy (i.e., to

their ‘appropriate flow of personal information’).

Specifically, we distinguish three main types of

relationship (or context) in which privacy is

important: between an individual and (i) other

individuals or groups (‘interpersonal privacy’); (ii) a

public or third sector (not-for-profit) organisation

(‘institutional privacy’); or (iii) a commercial (for-

profit) organisation (‘commercial privacy’).

Interpersonal privacy

We found that the predominant amount of

attention to children’s privacy online relates to the

interpersonal dimension, and most of the existing

studies demonstrate that individual privacy

decisions and practices are influenced by the social

environment – how individuals handle sharing with

or withholding information from others, how

existing networks, communication and sharing

practices influence individual decisions, and how

desire for privacy is balanced with participation, self-

expression and belonging. Issues related to peer

pressure, offline privacy practices and concerns and

parental influences also form important connections

to the social dimension of privacy (Xu et al., 2008;

Heirman et al., 2013). Children’s online practices are

shaped by their interpretation of the social situation,

their attitudes to privacy and publicity and their

ability to navigate the technological and social

environment and development of strategies to

achieve their privacy goals. These practices

demonstrate privacy as a social norm, achieved

6

Linked to questions of the child’s right to privacy is a

debate, inflected differently in different countries and

cultures, regarding the parent’s rights over their child,

including the parent’s right to manage (or invade) their

child’s privacy. Archard, D. (1990) Child Abuse: parental

rights and the interests of the child. Journal of Applied

Philosophy 7(2), 183-94, Shmueli, B. and Blecher-Prigat, A.

(2011) Privacy for children. Columbia Human Rights Law

Review 42, 759-95.

through an array of social practices configured by

social conditions (boyd and Marwick, 2011; Utz and

Krämer, 2015).

For example, a qualitative study of UK children aged

13-16 and their use of social media found that

teenagers form ‘zones of privacy’ using different

channels for disclosure of personal information in a

way that allows them to maintain intimacy with

friends but sustain privacy from strangers and

sometimes, parents (Livingstone, 2008). Their

behaviour on social media demonstrated the

shaping role of social expectations in the peer group

and their own understanding of friendship and

intimacy on privacy norms and behaviours. Privacy

decisions are also influenced by factors such as the

privacy settings of one’s friends, the intensity of

social media use, gender, types of contacts on one’s

social media profile, privacy concerns, wanting to be

in control of one’s personal information, prior

negative experiences of sharing personal

information or parental mediation (Youn, 2008;

Abbas and Mesch, 2015).

Institutional privacy

In digital societies, the collection of children’s data

begins from the moment of their birth and often

includes large amounts of information collected

even before they reach the age of two (UNICEF,

2018). Institutionalised aspects of privacy where

data control is delegated to external agencies, such

as government institutions, is becoming the norm

rather than the exception in the contemporary

digital era (Young and Quan-Haase, 2013). Still, the

discussion of institutional privacy in relation to

children was much less prominent in the literature,

and when discussed it was mostly seen as a

legitimate effort to collect data, not raising the same

critical concerns that we see in relation to either

children’s own privacy practices or commercial

practices. The main attention was focused on the

technical solutions related to institutional privacy,

the improvement of safety features and techniques

to restrict unauthorised access (Al Shehri, 2017), but

not on what the purpose of this data gathering is,

how it is shared with others and what the longer-

term consequences might be.

Amongst the criticisms of institutional privacy are

the contribution of governments and local

authorities to the increase in personal data

gathering and their ability to request individual data

from industry, for example, in an attempt to predict

14

criminal or terrorist behaviour (Solove, 2015;

DefendDigitalMe, 2018). There is also the potential

of institutional administrative data, collected in

circumstances in which one would expect

confidentiality, to be shared across intra- and inter-

governmental, public and commercial institutions,

for purposes described as for ‘public benefit', such

as fraud prevention, health and welfare or

education.

Still, existing studies show that individuals care

about how their personal data is collected and

processed by public section organisations and what

this means for their privacy. For example, Bowyer et

al. (2018) explore how families perceive the storage

and handling of their data (personal data,

relationships, school records and academic results,

social support and benefits, employment, housing,

criminal records, general practitioner and medical

records, library usage) by state welfare and civic

authorities, using game-based interviews. The study

found that families often consider their data as

‘personal’ and want to be in control of it, especially

in relation to information perceived to be ‘sensitive’.

This was often prompted by recognised risks (of a

criminal, medical, welfare, social and psychological

nature) and fear of the consequences of mishandling

or misuse of the data (Bowyer et al., 2018). This

study, however, did not focus on children; it

considered them as part of the family. Similar

findings are discussed by Culver and Grizzle (2017)

who did a global survey with children and young

people (aged 14-25, no distinction made by age

groups) and found that 60% of the survey

respondents disagreed that governments have the

right to know all personal information about them

and 50% agreed that the internet should be free

from governments’ and businesses’ control.

However, 38% thought that governments have the

right to know this information if it would keep them

safe online and 55% said that their security was

more important than their privacy (Culver and

Grizzle, 2017).

Other research looked at institutionalised privacy in

relation to young adults (e.g., students and online

learning and monitoring platforms), but there was

little discussion of a parallel, institutionalised privacy

for children (e.g., digital learning platforms,

fingerprint access to school meals, profiling of

attendance and academic performance). In fact,

these new approaches to digital learning are often

presented as ‘revolutionary’ and transformational to

parents, even though they raise many questions in

relation to the merging of for-profit platforms and

business models with public education (Williamson,

2017).

The potential risks behind institutional privacy are

demonstrated by a study of American schools

exploring the use of third-party applications and

software to monitor and track students’ social media

profiles and use during and after school (Shade and

Singh, 2016; Bulger et al., 2017). The research

demonstrated that, while the monitoring is justified

by school governors as an attempt to tackle bullying,

violence and threats by and directed at students, the

business imperatives raise ethical concerns about

young people’s right to privacy under a regime of

commercial data monitoring. Some of the examples

included in the study comprised monitoring and

analysing public social media posts made by

students aged 13+ and reporting on a daily basis

posts flagged as a cause for concern to school

administrators. The reports included screenshots of

flagged posts, whether they were posted on/off

campus, time and date and user’s name and

highlighted posts reflective of harmful behaviour to

students, as well as actions that are harmful to

schools themselves – shifting from an interest in the

safety of youth to the protection of the school. It

was unclear if the businesses cross-reference their

data with other records or information available,

creating an assemblage of surveillance (Shade and

Singh, 2016). While this demonstrates the potential

risks, more research is needed to fill in the gaps

related to how children and teenagers experience

institutional privacy, so as to draw further attention

to the management of informed consent and

children’s rights in settings such as schools and

health services (Lievens et al., 2018).

Commercial privacy

The means for processing children’s data are

advancing and multiplying rapidly, with commercial

companies gathering more data on children than

even governments do or can collect (UNICEF, 2018),

pushing commercial data collection to the top of the

privacy concerns. Marketers employ many, often

invasive, methods to turn children’s activities into a

commodity (Montgomery et al., 2017), monitoring

of online use and profiling via cookie-placing,

location-based advertising and behavioural

targeting. They also encourage young consumers to

disclose more personal information than necessary

15

in exchange for enhanced online communication

experiences (Bailey, 2015; Shin and Kang, 2016), or

as a trade-off for participation and access to the

digital services and products provided (Micheti et al.,

2010; Lapenta and Jørgensen, 2015). The invasive

tactics used by marketers to collect personal

information from children aiming to reach and

appeal to them as a designated target audience

have led to rising data privacy and security concerns

(Lupton and Williamson, 2017). These particularly

relate to children’s ability to understand and

consent to such data collection and the need for

parental approval and supervision, particularly in

relation to children under the age of 13 (or higher in

some countries in Europe)

7

(Livingstone, 2018).

While the commercial use of children’s data is at the

forefront of current privacy debates, the empirical

evidence lags behind, with very few studies

examining children’s awareness of commercial data

gathering and its implications. The majority of

research on young people in this area is based on

young adults (18+) or older teenagers (16+), and

demonstrates that even these more mature online

users have substantial gaps in their privacy

knowledge and awareness. Some of the barriers that

have been identified by the existing research on

children’s understanding of commercial privacy

relate to the incomprehensibility of how their online

data is being collected and used (Emanuel and

Fraser, 2014; Acker and Bowler, 2018), how it flows

and transforms – being stored, shared and profiled

(Bowler et al., 2017), and to what effect and future

consequence (Murumaa-Mengel, 2015; Bowler et

al., 2017; Pangrazio and Selwyn, 2018). While the

research demonstrates that some commercial

privacy concerns exist (related to being tracked

online, that all the data is stored permanently, the

inability to delete one’s data), children generally

display some confusion of what personal data means

and a general inability to see why their data might

be valuable to anyone (Lapenta and Jørgensen,

2015).

The existing evidence also suggests that children

may also provide personal data passively and

unconsciously when using online services like social

media, provoked by the platform design and

configuration (De Souza and Dick, 2009; Madden et

al., 2013; Pangrazio and Selwyn, 2018; Selwyn and

Pangrazio, 2018). Generally, children are more

7

Parental consent is required for underage children only

when data is processed on the basis of consent.

concerned about not being monitored by parents

(Shin et al., 2012; Third et al., 2017) or about breach

of privacy by friends and by unknown actors (such as

hackers, identity thieves and paedophiles), and less

so about the re-appropriation of their data by

commercial entities.

Children also struggle with privacy statements due

to their length and complicated legal language or

the inefficient management of parental consent by

children’s websites (Children's Commissioner for

England, 2017b) which either overlook, detour or

avoid parental consent. Some children may feel

obliged to agree with the Terms and Conditions and

they see targeted advertising as a default part of

contemporary life (Lapenta and Jørgensen, 2015).

The evidence also suggests that children do not feel

that they can change their behaviour much, feel

unable to invest the time needed to constantly

check the privacy settings, and are not sure how to

avoid data profiling (Lapenta and Jørgensen, 2015;

Pangrazio and Selwyn, 2018). As a result, they

experience a contradiction between their desire to

participate and the wish to protect their privacy, in a

way that might cause a sense of powerlessness

(Lapenta and Jørgensen, 2015; Pangrazio and

Selwyn, 2018; Selwyn and Pangrazio, 2018).

There is some evidence that commercial privacy is

related to different behaviours than interpersonal

privacy resulting from the different type of follow-up

engagement: while individuals examine the reaction

of friends towards their posts on social media, they

do not often deliberately communicate with

commercial entities, so the consequences of their

data being used may remain unknown to them,

making them less concerned about commercial than

interpersonal privacy (Lapenta and Jørgensen,

2015). Better knowledge of commercial privacy,

however, can be associated with a greater desire to

have control over the display of advertising content.

A study of 363 adolescents aged 16-18 from six

different schools in Belgium showed that as their

level of privacy concern increased, so did their

sceptical attitudes towards advertisement targeting,

resulting in lower purchasing intention: ‘This

demonstrates that adolescents adopt an advertising

coping response as a privacy-protecting strategy

when they are more worried about the way

advertisers handle their online personal information

for commercial purposes’ (Zarouali et al., 2017:

162). This demonstrates the importance of exploring

commercial privacy in relation to children,

16

particularly with a developmental (Fielder et al.,

2007) and educational/media literacy focus as so far

we lack sufficient up-to-date research.

Types of digital data

Figure 2: Dimensions of privacy and types of data

With digital media now being embedded, embodied

and everyday (Hine, 2015), the contemporary digital

world has become ‘data-intensive, hyper-connected

and commercial’ as an increasing amount of data is

being collected about online users, including

children (van der Hof, 2016: 412; Winterberry

Group, 2018). To capture this comprehensive

collection of data and to think about what children

know and expect in relation to different types of

data, we adapted a typology from privacy lawyer

Simone van der Hof (2016) to distinguish:

Data given – the data contributed by individuals

(about themselves or about others), usually

knowingly though not necessarily intentionally,

during their participation online.

Data traces – the data left, mostly unknowingly–

by participation online and captured via data-

tracking technologies such as cookies, web

beacons or device/browser fingerprinting,

location data and other metadata.

Inferred data – the data derived from analysing

data given and data traces, often by algorithms

(also referred to as ‘profiling’), possibly

combined with other data sources.

Each of these types of data may or may not be

‘personal data’, that is, ‘information that relates to

an identified or identifiable individual’, as defined by

the ICO and GDPR.

8

The different dimensions of privacy incorporate

different types of data (see Figure 2) and therefore,

represent different degrees of ‘invasiveness’

(indicated by the intensity of the colour of the

boxes), especially having in mind that only one type

of data is actively contributed by individuals – the

‘data given’

When considering privacy online, do children think

mostly about their individual privacy and the data

they or others (friends or family) share about them

online? How knowledgeable are they about the data

traces they leave and about how these can be used

to profile them (inferred data) for commercial

purposes?

8

For more on ‘personal data’ see What is personal data?

(https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/guide-to-the-

general-data-protection-regulation-gdpr/key-

definitions/what-is-personal-data/).

Interpersonal

privacy

Data given

Data given off

Inferences

Institutional

privacy

Data given

Data traces

(knowingly)

Inferred data

(analytics)

Commercial

privacy

Data given

Data traces

(taken)

Inferred data

(profiling)

17

5.3. Privacy and child development

Research shows that children of different ages have

different understanding and needs. The truth of this

claim does not mean it is easy to produce age

groupings supported by evidence, nor that children

fall neatly into groupings according to age; they do

not. Any age group includes children with very

different needs and understandings. Even for a

single child, there is no magic age at which a new

level of understanding is reached. The academic

community has, by and large, moved beyond those

early developmental psychology theories which

proposed strict ‘ages and stages’. But nor does it

consider children to be equivalent from the age of 5

and 15, for instance. Rather, developmental

psychology, like clinical psychology and, indeed, the

UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, urges that

children are treated as individuals, taking into

account their specific needs, understandings and

circumstances.

While children develop their privacy-related

awareness and literacy as they grow older, their

development is multifaceted and complex; it does

not fall neatly into simple stages or change suddenly

once they pass their birthday. In addition, children’s

development can be very different based on their

personal circumstances. For example, a 15-year-old

from a low socio-economic status (SES) home (DE)

might have similar knowledge and digital literacy as

a 11-year-old from a high SES home (AB), as we

show here (Livingstone et al., 2018a). Hence, we

urge that consideration of age groups and age

transitions considers cognitive, emotional and

social/cultural factors. For instance, in the UK,

around the age of 11, most children move from

smallish, local primary schools to large, more distant

secondary schools. Many risky practices – online and

offline – occur at this transition point, because

children are under pressure quickly to fit into a new

and uncertain social context. They are likely, then,

for social and institutional (rather than cognitive)

reasons, to access many new apps and services, to

feel pressured to circumvent age restrictions, to

provide personal information not provided before,

and so forth. To give another instance, children who

suffer risks or hardships or disabilities in their day-

to-day world are likely to experience different

pressures to join in online, again meaning that

consideration of their age alone would fail to fulfil

their best interests.

However, child development theory and some

existing evidence points to the diverse

understandings and skills that children acquire, test

and master at different ages and its subsequent

influence on their online interactions and

negotiations. The evidence suggests that design

standards and regulatory frameworks must account

for children’s overall privacy needs across age

groups, and pay particular attention and

consideration to the knowledge, abilities, skills and

vulnerabilities of younger users. Chaudron et al.’s

(2018) study of young children (aged 0-8) across 21

countries found that most children under 2 in

developed countries have a digital footprint through

their parents’ online activities. Children’s first

contact with digital technologies and screens was at

a very early age (below the age of 2) often through

parents’ devices, and they learn to interact with

digital devices by observing adults and older

children, learning through trial and error and

developing their skills. They did not have a clear

understanding of privacy or know how to protect it.

The Global Kids Online study observed clear age

trends in four countries, where older children were

more confident in their digital skills than their

younger counterparts. Young children (aged 9-11) in

particular showed less competence in managing

their online privacy settings than teens (aged 12-17)

(Byrne et al., 2016).

Privacy is vital for child development – key privacy-

related media literacy skills are closely associated

with a range of child developmental areas –

autonomy, identity, intimacy, responsibility, trust,

pro-social behaviour, resilience, critical thinking and

sexual exploration (Peter and Valkenburg, 2011;

Raynes-Goldie and Allen, 2014; Pradeep and Sriram,

2016; Balleys and Coll, 2017). Online platforms

provide opportunities for development (while also

introducing and amplifying risks) that children can

use to build the skill entourage that they need for

their growth (Livingstone, 2008). There is also solid

evidence that understanding of privacy becomes

more complex with age and that the desire for

privacy also increases (Shin et al., 2012; Kumar et al.,

2017; Chaudron et al., 2018).

Despite the relationship between child development

and privacy functioning and competencies, the

evidence on this is patchy. How do children

understand and manage privacy based on their age

and development? What is the most suitable age to

start learning about privacy online, and how should

18

this learning expand as children grow up and

develop? These are important questions, which the

systematic evidence mapping could not answer

sufficiently. Due to the nature of the existing

research, it is difficult to provide robust evidence to

support strictly identified age brackets and to cover

the full age spectrum under 18 years. A large

number of studies focus on 12- to 18-year-olds,

paying much less attention to younger cohorts and

studies rarely disaggregate findings amongst the

different age groups (Livingstone et al., 2018b).

Further difficulties arise from the fact that current

evidence on children’s privacy concerns, risks and

opportunities utilises a range of age brackets and

applies them inconsistently.

Attempting to overcome the above difficulties and

boiling the research down to its essence, we

mapped the development of children’s

understanding of privacy by age, with the caveat

that the differences within as well as across age

groups can be substantial. We identified three

groups of evidence (see Table 2 below): children

aged 5-7, 8-11 and 12-17. Hence, we think that

there is little evidence to support the more nuanced

differences in the age groups at present.

Table 2: Child development and types of privacy

Interpersonal privacy

Institutional and commercial privacy

5- to 7-

year-olds

• A developing sense of ownership,

fairness and independence

• Learning about rules but may not

follow, and don’t get consequences

• Use digital devices confidently, for a

narrow range of activities

• Getting the idea of secrets, know how

to hide, but tend to regard

tracking/monitoring as helpful

• Limited evidence exists on

understanding of the digital world

• Low risk awareness (focus on device

damage or personal upset)

• Few strategies (can close the app, call

on a parent for help)

• Broadly trusting

8- to 11-

year-olds

• Starting to understand risks of sharing

but generally trusting

• Privacy management means rules not

internalised behaviour

• Still see monitoring positively, as

ensuring their safety

• Privacy risks linked to ‘stranger

danger’ and interpersonal harms

• Struggle to identify risks or distinguish

what applies offline/online

• Still little research available

• Gaps in ability to decide about

trustworthiness or identify adverts

• Gaps in understanding privacy terms

and conditions

• Interactive learning shown to improve

awareness and transfer to practice

12- to 17-

year-olds

• Online as ‘personal space’ for

expression, socialising, learning

• Concerned about parental monitoring

yet broad trust in parental and school

restrictions

• Aware of/attend to privacy risks, but

mainly seen as interpersonal

• Weigh risks and opportunities, but

decisions influenced by desire for

immediate benefits

• Privacy tactics focused on online

identity management not data flows

(seeing data as static and fragmented)

• Aware of ‘data traces’ (e.g., ads) and

device tracking (e.g., location) but less

personally concerned or aware of

future consequences

• Willing to reflect and learn but do so

retrospectively

• Media literacy education best if teens

can use new knowledge to make

meaningful decisions

19

5- to 7-year olds

Starting with the youngest group we identified – the

5- to 7-year-old children – we found that there is

limited evidence on their understanding of privacy,

but the existing studies suggest that children of this

age are already starting to use services which collect

and share data - for example, 3% of the UK children

aged 5-7 have a social media profile and 71% use

YouTube (Ofcom, 2017b). Children of this age

gradually develop a sense of ownership and

independence, as well as the ability to grasp

‘secrecy’ that is necessary for information

management abilities and privacy (Kumar et al.,

2017). While children are confident internet users,

they engage in a narrow range of activities and have

low risk awareness (Bakó, 2016). They do not

demonstrate an understanding that sharing

information online can create privacy concerns