Operational policy

Page 1 of 7 • QPW/2015/1430 v2.03 ABN 46 640 294 485

Natural Resource Management

Management of wild dogs on QPWS estate

Operational policies provide a framework for consistent application and interpretation of legislation and for the management

of non-legislative matters by the Department of Environment and Science (DES). Operational policies are not intended to be

applied inflexibly in all circumstances. Individual circumstances may require a modified application of policy.

Policy subject

This document provides a policy framework and procedural guide for managing wild dogs on the Queensland

Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS) managed areas.

Definitions

The following definitions apply within this document.

Authority holder means persons issued an authority (i.e. stock grazing lease or permit) over QPWS managed

areas.

Dingo Canis familiaris (dingo) means native dogs of Asia, selectively bred by humans from wolves. Present in

Australia before domestic dogs, pure dingoes are populations or individuals that have not hybridised with

domestic dogs or hybrids.

Hybrids means dogs resulting from crossbreeding of a dingo and a domestic dog and their descendant

progeny.

Peri-urban means landscape combining urban and rural areas such as suburban and rural residential lots and

smaller agricultural holdings (as mapped in the Queensland Wild Dog Management Strategy 2011-16).

Tenure blind means planning process or approach where a range of control methods are applied across all

tenures by all stakeholders at a ‘landscape’ (rather than ‘property’) level in a cooperative and coordinated

manner.

Wild dogs means all wild-living dogs (including dingoes, feral or wild living domestic dogs and hybrids).

QPWS managed areas means land managed by QPWS under Nature Conservation Act 1992, Forestry Act

1959 and Recreation Areas Management Act 2006.

Background

QPWS is required to manage wild dogs, including dingoes, consistent with a range of legal obligations. Wild

dogs have social, economic and environmental impacts and there is strong public concern about attacks on

livestock, humans and pets. Wild dogs kill wildlife and can also spread disease and parasites to stock, pets,

humans and wildlife. Wild dog management must also address animal welfare issues and avoid impacts on non-

target species.

There are complex ecological relationships between wild dogs, native wildlife (including threatened species) and

other vertebrate pests such as pigs, foxes and cats. The scientific evidence for this is not clear but as a top

Operational policy

Management of wild dogs on QPWS estate

Page 2 of 7 • QPW/2015/1430 v2.03 Department of Environment and Science

order predator dingoes are considered to fill an important ecological niche; maintaining ecosystem structure and

stability through their interactions with smaller predators and herbivores. In particular, dingoes may reduce

predation by foxes and cats on small mammals, reptiles and birds, including threatened species. Dingoes are

iconic native animals and there is community expectation that core populations will be conserved as part of

natural ecosystems. Cross breeding between dingoes and other wild dogs creates hybrids, dilutes dingo

genetics and provides challenges for management.

Legal and strategic context

Dingoes are recognised as ‘native wildlife’ under the Nature Conservation Act 1992 and therefore protected as

‘natural resources’ within protected areas. Under the Forestry Act 1959, the dingo is protected as a ‘forest

product’ within State forests.

Dingoes have no legal protection outside protected areas and State forests. Wild dogs, including dingos, are

declared restricted matter under the Biosecurity Act 2014 and landholders must take reasonable steps to keep

their land free of wild dogs.

The Queensland Wild Dog Management Strategy 2011-16 provides a State-wide framework for wild dog

management. The strategy promotes a ‘tenure blind’ approach and supports the conservation of dingoes on

QPWS managed areas, including practical measures to reduce hybridisation of dingo populations. The strategy

also sets out objectives for three broad management zones across the State: 1) Inside the Wild Dog Barrier

Fence (WDBF) - zero tolerance of wild dogs; 2) Outside the WDBF - control wild dogs and; 3) Peri-urban zone -

reduce impacts of wild dogs in coastal, semi-urban and rural environments.

Dingo Conservation

Dingo populations need to be maintained on protected areas to protect the biodiversity of Queensland’s natural

ecosystems. The Queensland Wild Dog Management Strategy 2011-16 provides objectives for conserving

dingo populations in Queensland, including:

• applying a contemporary understanding of dingo genetics, identification and population ecology;

• managing populations of dingoes of conservation significance, including preventing hybridisation by

removing other wild dogs; and

• balancing the conservation of the dingo with other strategy objectives, such as managing public safety

and economic impacts on neighbouring rural enterprises.

Policy statements

• QPWS will conserve dingo populations on protected areas to maintain biodiversity and natural

ecological processes.

• QPWS will manage wild dogs to meet its pest management obligations and to mitigate threats to native

wildlife and other values of QPWS managed areas, public safety and the economic and social well-

being of neighbouring lands and communities.

• Approved wild dog control measures can be used on QPWS managed areas where they are part of

integrated and coordinated control programs. Wild dog control measures will generally be limited to the

perimeter of these lands as per the procedures.

• Where appropriate, QPWS will consult and work in partnership with neighbours, authority holders, other

government agencies and interest groups to manage wild dogs in the broader landscape.

Operational policy

Management of wild dogs on QPWS estate

Page 3 of 7 • QPW/2015/1430 v2.03 Department of Environment and Science

Authority holders

Authority holders, such as lessees, will usually have primary responsibility for wild dog management. They must

gain approval from QPWS prior to carrying out wild dog control to ensure public safety and to agree on

guidelines, location, timing and control methods. If authorities do not specify these responsibilities, QPWS will

seek an approach that benefits wild dog management and ecological outcomes consistent with the needs of

authority holders. QPWS reserves the right to carry out wild dog control measures on QPWS managed areas

after consultation with the authority holder.

Control measures undertaken by authority holders must comply with accepted Codes of Practice and Standard

Operating Procedures adopted by QPWS and other agencies.

Procedures

Planning and consultation

QPWS wild dog management programs will be consistent with the QPWS Pest Management System, including

planning, approvals, implementation and evaluation. Planning for wild dog control programs will:

• adopt a ‘tenure blind’ approach and, where appropriate consult and engage in cooperative partnerships

with neighbours, baiting syndicates and wild dog committees, traditional owners, authority holders, other

State government agencies and local authorities;

• provide measurable and achievable objectives, including clear timeframes for outcomes, recognising

limits to available resources;

• be based on integrated pest animal management principles; and apply a contemporary understanding

of wild dog management and dingo ecology and conservation;

• provide clear justification and evidence for proposed management actions including documenting the

type, location and extent of wild dog impacts (including environmental and economic impacts) and

public safety;

• assess risks to ensure control programs will not adversely impact on biodiversity, threatened species,

non-target species (i.e. the viability of core dingo populations) or natural ecological process; and

• consider the objectives of management zones in the Queensland Wild Dog Management Strategy 2011-

16.

While the ecological relationship between wild dogs, wildlife, stock and vertebrate pests are complex and the

subject of ongoing research, planning for wild dog control programs should consider the following issues:

• the latest scientific research and best practice relating to wild dog ecology and control;

• the impact of wild dogs on wildlife, vertebrate pests and stock varies from location to location depending

on factors such as vegetation, mix and abundance of species and availability of other food sources;

• wild dogs should be considered an integral component of natural ecosystems and may predate or

otherwise suppress vertebrate pests such as cats, pigs and foxes to the benefit of native wildlife.

Proposals to remove wild dog control must assess potential for increased predation on wildlife by such

vertebrate pests;

• wild dogs may impact on some wildlife populations (particularly herbivores such as macropods) or

provide a threat to specific populations of threatened species (e.g. bilby or bridled nail-tailed wallaby);

• inappropriate control programs may destabilise or change the dynamics of wild dog populations and

have the potential to increase impacts on stock or wildlife; and

Operational policy

Management of wild dogs on QPWS estate

Page 4 of 7 • QPW/2015/1430 v2.03 Department of Environment and Science

• indiscriminate baiting for wild dogs may only result in short term, localised reductions in wild dog

numbers with new dogs quickly moving in to replace those removed.

Wild dog control measures

Wild dog control measures on QPWS managed areas will generally be limited to within fifty metres inside

the boundary of the estate unless alternative approaches and locations are clearly justified and approved. It is

acknowledged that deviations from the perimeter may be required where part of a boundary is inaccessible due

to terrain or not appropriate for baiting (e.g. is bounded by a large water body) (refer to Table 1).

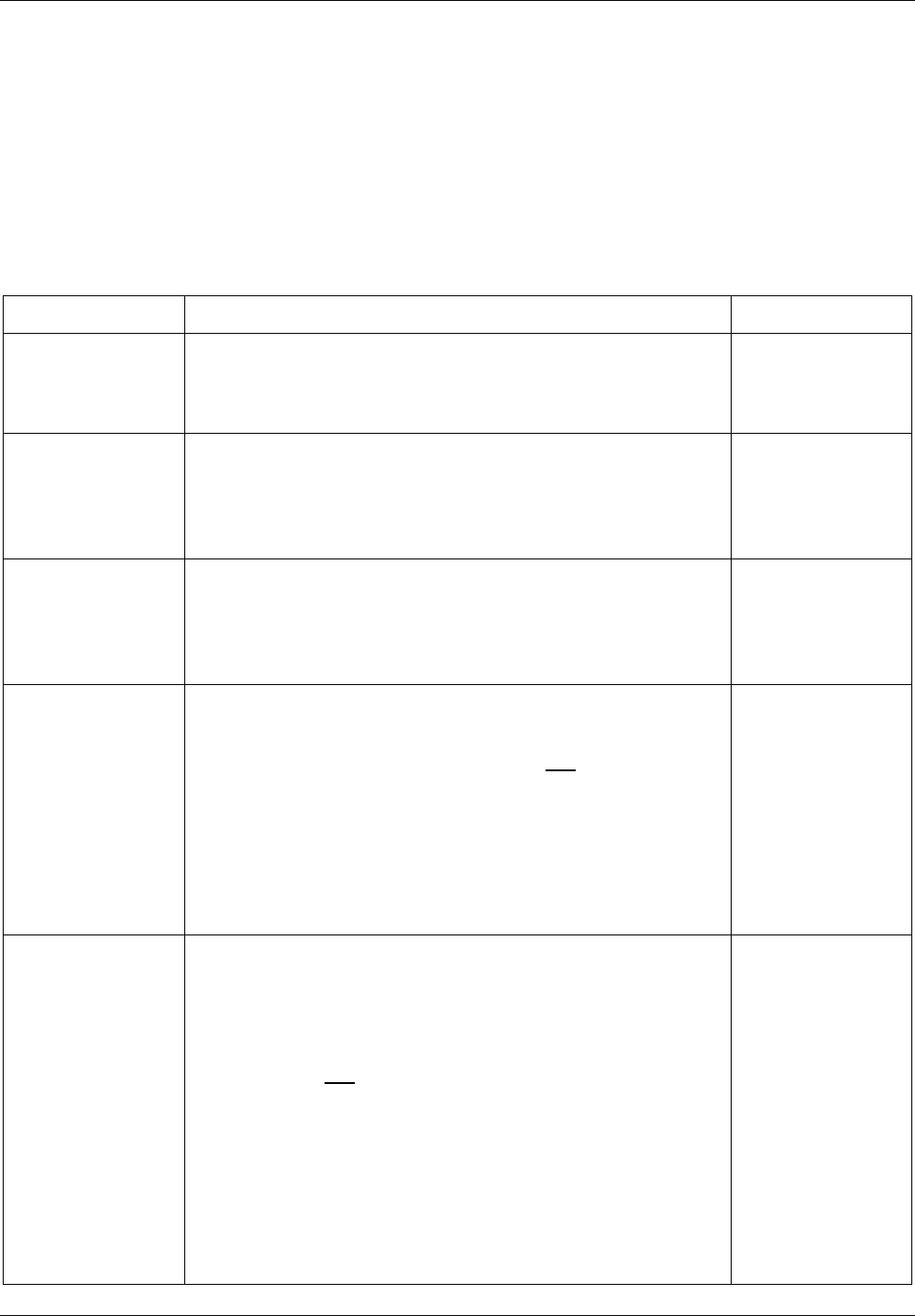

Table 1: Approvals and appropriate use of wild dog control measures on QPWS estate

Control Measure Appropriate use / justification of control measure

1

Approvals

2

Trapping Appropriate for small populations / individual problem dogs.

Appropriate for use on estate perimeter, unless alternative

approach and specific locations are clearly justified.

Regional Director’s

or delegate.

Shooting Appropriate for small populations / individual problem dogs.

May not be appropriate in some peri-urban areas due to public

safety issues (i.e. subject to risk assessment).

Regional Director’s

or delegate.

Regional Director

for firearm use.

Perimeter baiting Appropriate for use on estate perimeter, unless alternative

approach and specific locations are clearly justified.

May not be appropriate in some peri-urban areas due to risks to

domestic animals.

Regional Director

for ground and

aerial baiting

4

.

Perimeter bait

stations

Generally not appropriate, unless there is:

• a ‘major’ to ‘significant’ economic threat

3

to neighbouring

rural enterprises (i.e. stock losses) and potential impacts

of baiting on conservation values (i.e. non-target

species) are low; or

• a ‘moderate’ to ‘significant’ threat

3

to threatened

species.

The method will not be appropriate in most peri-urban areas.

Regional Director

Broadscale

baiting

(on QPWS estate).

Not appropriate unless there is:

• a ‘moderate’ to ‘significant’ threat

3

to threatened species

• a ‘significant’ economic threat

3

demonstrated to be

occurring on neighbouring rural properties (i.e. stock

losses) and where:

o there is a known threat to protected wildlife on

the estate; and

o risk assessment shows the potential impacts of

baiting on conservation values (i.e. non-target

species) are considered to be low;

o it is part of a collaborative landscape approach;

Regional Director

for ground and

aerial baiting

4

.

Operational policy

Management of wild dogs on QPWS estate

Page 5 of 7 • QPW/2015/1430 v2.03 Department of Environment and Science

o it is inside the Wild Dog Barrier Fence.

The method is not appropriate in peri-urban areas.

1

All control measures must be evidence based, justified and assessed on merit through Pest Management

System processes and address requirements identified under ‘Planning and Consultation’ of this procedure.

Local variables make it difficult to prescribe definitive thresholds to justify a control measure and may include

economic factors, known wild dog hot spots, human-wild dog interface, Queensland Wild Dog Management

Strategy management zones, planned coordinated actions and characteristics of threatened species

populations.

2

All approvals are provided following review and endorsement by relevant Regional Pest Referral Group.

3

‘Threat’ levels are provided as a guide and are described in the QPWS Pest Management System.

4

Ground baiting should be the first preference. Aerial baiting will only be approved if ground baiting is

significantly constrained by terrain, in large and remote lands where the threat to non-target species and

neighbouring lands is minimal, where aerial baiting is the most cost effective method and where rotary winged

aircraft will be used.

In addition to the methods listed in Table 1, non-lethal methods may also be used in special circumstances. For

example, exclusion fencing and aversion techniques are used on Fraser Island for the management of dingoes.

Baits must consist of registered vertebrate pesticides, such as sodium fluoroacetate (1080). All use of sodium

fluoroacetate must be consistent with Operational Policy – Use of sodium fluoroacetate (compound 1080) for

poison baiting and Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (DAF) Toxic 1080 A guide to safe and responsible

use of fluoroacetate in Queensland and DAF Vertebrate Pesticide Manual – A guide to using fluoroacetate,

PAPP and strychnine in Queensland.

Humane destruction of wild dogs using firearms must be consistent with the QPWS Firearms Manual.

Contracts may be approved for pest animal control activities, using one or more of the control methods listed in

Table 1 and will be subject to a relevant authority and contractual requirements.

The DAF Wild Dog facts and Wild dog control planning calendar provides information to assist effective wild dog

management. The Queensland Wild Dog Management Strategy 2011-16 and the DAF information web pages,

provide detailed information on the ecology, description, habitat, reproduction and behaviour of wild dogs.

Prohibited control methods

Control methods that are not approved for use on QPWS managed areas are as follows.

• Strychnine hydrochloride, strychnine alkaloid toxins for poisoned baits or the use of strychnine treated

cloth as part of a lethal trap device is not permitted (e.g. due to animal welfare concerns and the

potential for secondary poisoning of non-target species).

• Steel-jawed traps.

Animal welfare

QPWS staff must comply with the Animal Care and Protection Act 2001 and other animal welfare policies and

procedures.

The efficiency and effectiveness of current and potential management methods must comply with the PestSmart

Code of practice for the humane control of wild dogs’ and balance animal welfare concerns with public and staff

safety.

Operational policy

Management of wild dogs on QPWS estate

Page 6 of 7 • QPW/2015/1430 v2.03 Department of Environment and Science

Monitoring, evaluation and reporting

Where practicable, monitoring and evaluation of wild dog activity and control programs should be undertaken to

determine whether:

• the environmental, economic and social impacts attributed to wild dogs were accurate and what factors

were involved;

• the control program was effective and objectives were achieved;

• the pest problem or control activity needs to be reassessed and possible improvements;

• the pest impact changes over time (e.g. a reduction in wild dog activity and impacts or production losses

on neighbouring land); and

• the control activity had an effect on other species and natural ecological processes.

Monitoring cameras may be used to determine wild dog activity before and after a control program. If it is not

possible to establish monitoring cameras or transects in each parcel of estate being baited, several

representative camera locations or transects may be established. Impacts resulting from wild dog activity should

be documented to monitor post control outcomes.

References

Nature Conservation Act 1992

Forestry Act 1959

Biosecurity Act 2014

Animal Care and Protection Act 2001

Queensland Wild Dog Management Strategy 2011-16

Toxic 1080 A guide to safe and responsible use of fluoroacetate in Queensland (DAF)

Vertebrate Pesticide Manual – A guide to using fluoroacetate, PAPP and strychnine in Queensland (DAF)

Code of practice for the humane control of wild dogs (PestSmart)

Medicines & Poisons (Poisons & Prohibited Substances) Regulation 2021

Pest Management System

Operational policy – Good Neighbour Policy

Operational policy – Use of sodium fluoroacetate (compound 1080) for poison baiting

Procedural guide – Use of sodium fluoroacetate (compound 1080) for poison baiting

Operational policy

Management of wild dogs on QPWS estate

Page 7 of 7 • QPW/2015/1430 v2.03 Department of Environment and Science

Disclaimer

While this document has been prepared with care, it contains general information and does not profess to offer legal,

professional or commercial advice. The Queensland Government accepts no liability for any external decisions or actions

taken on the basis of this document. Persons external to the Department of Environment and Science should satisfy

themselves independently and by consulting their own professional advisors before embarking on any proposed course of

action.

Approved By

Ben Klaassen

23 October 2015

Signature Date

Deputy

Director-General

Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service

Enquiries:

Fire and Pest, Technical Services

Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service

Email. pest.advice@des.qld.gov,au