Inclusion

Unified Sports, Social Inclusion and Athlete Reported Experiences: A Systematic

Mixed Studies Review

--Manuscript Draft--

Manuscript Number: INCLUSION-M-21-00027R2

Article Type: Research Article

Keywords: intellectual disability; self-concept; Special Olympics, students, synthesis

Corresponding Author: Amy Accardo

Rowan University

Glassboro, New Jersey UNITED STATES

First Author: Amy L Accardo

Order of Authors: Amy L Accardo

Sarah L Ferguson

Hind M Alharbi

Mary K Kalliny

Casey L Woodfield

Lisa J Vernon-Dotson

Manuscript Region of Origin: UNITED STATES

Abstract: Inclusive sports have emerged as a potential tool for building social inclusion within

diverse populations. The Special Olympics Unified Sports programs are an example of

inclusion initiatives specific to students with intellectual disabilities and sports that can

be reevaluated with new understandings of inclusion. This systematic mixed studies

review aimed to capture athlete Unified Sports experiences and identify what athletes

reported about their participation. The systematic review identified nine original studies

conducted by six unrelated research groups. Results across the studies are

synthesized and suggestions for future research are presented. Athletes in all nine

studies reviewed reported positive experiences with Unified Sports leading to

increased social inclusion and/or self-concepts.

Powered by Editorial Manager® and ProduXion Manager® from Aries Systems Corporation

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES

Unified Sports, Social Inclusion and Athlete Reported Experiences:

A Systematic Mixed Studies Review

Acknowledgments: This manuscript was made possible by funding received through New Jersey

Department of Education Grant PTE 500-20200022

Blinded Title Page Click here to access/download;Blinded Title Page;Blinded Title

Page.docx

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 1

Unified Sports, Social Inclusion and Athlete Reported Experiences:

A Systematic Mixed Studies Review

Abstract

Inclusive sports have emerged as a potential tool for building social inclusion within diverse populations.

The Special Olympics Unified Sports programs are an example of inclusion initiatives specific to students

with intellectual disabilities and sports that can be reevaluated with new understandings of inclusion.

This systematic mixed studies review aimed to capture athlete Unified Sports experiences and identify

what athletes reported about their participation. The systematic review identified nine original studies

conducted by six unrelated research groups. Results across the studies are synthesized and suggestions

for future research are presented. Athletes in all nine studies reviewed reported positive experiences

with Unified Sports leading to increased social inclusion and/or self-concepts.

Keywords: intellectual disability, self-concept, Special Olympics, students, synthesis

Edited Manuscript Click here to access/download;Edited Manuscript;1. Unified

Sports, Social Inclusion REVISED II.docx

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 2

Unified Sports, Social Inclusion and Athlete Reported Experiences:

A Systematic Mixed Studies Review

In a post pandemic world as we face the effects of Covid-19 and systemic racism, schools

worldwide are focusing on the importance of social inclusion for students with various intersecting

socio-economic, religious, cultural, and linguistic backgrounds, sexual orientations, gender identities,

and even immigrant status (Schwab et al., 2018). As we broaden the lens of inclusion initiatives to

center disability, students become comfortable understanding disability as diversity. Meeting the social

needs of students is a crucial aspect of inclusion initiatives (Siperstein et al., 2017). The Special Olympics

Unified Sports programs (Baran et al., 2009) are an example of inclusion initiatives specific to students

with intellectual disabilities and sports that can be reevaluated with new understandings of inclusion.

Social Inclusion

Inclusion is recognized as a dynamic process that involves navigating interpersonal relationships,

environmental opportunities, as well as socio-political factors that change across various social contexts

of life for each individual (McConkey et al., 2019). Social inclusion can be defined as an interaction

between interpersonal relationships and community involvement, two major life domains (Simplican et

al., 2015). Community-wide social inclusion is a significant priority for people with disabilities, their

families, policymakers, and service providers (Simplican et al., 2015) as inclusion reduces the stigma

associated with disability and provides opportunities for social development (Lopes, 2015). Social

inclusion enables all members of the community to acquire vital skills, develop a sense of belonging, and

build independence (Kiuppis, 2018). In terms of social inclusion, centering disabled

1

students’ voices and

1

We use the terms “with a disability” and “disabled” interchangeably throughout this paper to show

acceptance of both professional use of person-first language and the preference of many members of

the disability community for identity-first language.

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 3

perspectives in the conversation about what works for them is essential to capture their needs and

priorities (Connor et al., 2008).

Inclusive sports have emerged as a potential tool for building social inclusion within diverse

populations. Sports are considered important within society. Involvement in sports may help eliminate

social exclusion within the community (Haudenhuyse, 2017) and promote marginalized groups' social

inclusion (Grandisson et al., 2019). Sports have been found to empower disabled people by helping

them realize their full potential and their ability to advocate for societal changes (Kiuppis, 2018). Social

inclusion through sports is regarded internationally as a means for people with disabilities to increase

their social networks (McConkey & Menke, 2020). Through the involvement of school-age students with

intellectual disabilities in sports, stigma and discrimination associated with their status may be reduced.

A good example of an approach that centers social inclusion through sports is Special Olympic Unified

Sports, which has exemplified the popularity of inclusive sports on an international scale.

Special Olympics Unified Sports

The Special Olympic Unified Sports program is built on the premise that active involvement as

part of a sports team provides natural opportunities for friendship formation (Baran et al., 2009).

Unified Sports teams are formed of individuals with and without disabilities of similar sporting ability

and age who train and play together (Siperstein & Hardman, 2001; Baran et al., 2009). While the

program was founded on the principle of promoting friendship and understanding, it has shown to have

many other benefits such as providing young people with disabilities the opportunity to play sports, and

to interact with other kids and have fun (Unified Sports, n.d.). Unified Sports provides a selection of

indoor and outdoor sports such as basketball, bowling, golf, softball, and volleyball. Through

participation in Unified Sports, individuals with intellectual disabilities are provided opportunities to

enhance their sports skills and to encounter new experiences and challenges which have been found to

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 4

lead to improved self-esteem and the development of friendships (Baran et al., 2009; Castagno, 2001;

Roswal, 2007; Siperstein & Hardman, 2001).

The Special Olympics organization launched Unified Sports in 1989, and today Unified Sports has

an international presence (Special Olympics Unified Sports, 2012, p. 1). According to the Special

Olympics website, Unified Sports are played in more than 4500 elementary, middle, and high schools in

the United States and the program has also expanded to universities. Moreover, a large number of

influential organizations such as Lions Club international have become strong global supporters in

expanding Unified Sports by partnering with Special Olympics. Major sports organizations and leagues

such as the National Basketball Association (NBA), Major League Soccer (MLS), Union of European

Football Associations (UEFA), National Collegiate Athletic Association, D-III, ESPN's X Games Aspen,

National Federation of High Schools (NFHS), and National Intramural-Recreational Sports Association

(NIRSA) are also supporting the program by presenting it as a mean to show the power of Unified Sports

(Unified Sports, n.d.). In addition, several major corporations and foundations such as The Coca-Cola

Company and the Samuel Family Foundation are partners in these efforts (Special Olympics, n.d.).

Unified Sports Perspectives

Much of what is known about athletes’ experiences in sports comes from the perspectives of

nondisabled athletes (Harada & Siperstein, 2009). Within the literature focused on sports experiences of

athletes with disabilities, research focuses on parasports (e.g., Allan et al., 2018), traditional Special

Olympics programming as opposed to Unified Sports initiatives (e.g., Hamandi et al., 2019) and/or the

perspectives of adult participants (e.g., Dailey, 2020). Even within literature specifically focused on the

experiences of participants in Unified Sports, studies focus on attitudes of students without disabilities

(e.g., Siperstein et al., 2017; Townsend & Hassell, 2007). Other research has reported on the impacts of

Unified Sports programs across a variety of stakeholders, including athletes and partners (Castagno et

al., 2001; McConkey et al., 2019; McConkey & Menke, 2020; Ozer et al., 2012; Wilski et al. 2012), as well

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 5

as coaches and parents (Baran et al., 2009; Hassan et al., 2012; McConkey et al., 2013). This literature

offers a broad perspective on the impacts of Unified Sports across stakeholder groups, and highlights

the reciprocal benefits of these inclusive sports activities.

Student Reported Experiences

As a team of researchers newly connected to Unified Sports through a University-state

partnership, we set out to understand the comprehensive published research literature on Unified

Sports and social inclusion with a focus on prioritizing the existing research eliciting athlete reported

Unified Sports experiences in response to the dearth of research centering their perspectives. The

decision was made to focus on student athletes participating in school-age Unified Sports programs as

we aimed to gain an understanding of the impact of Unified Sports Experiences within K-21 education

communities, specifically the experiences of children and young adults with disabilities. Gathering

students’ perspectives results in a “more holistic evaluation of the inclusion in school” (Schwab et al.,

2018, p. 38). In terms of social inclusion, centering disabled students in the conversation about what

works for disabled students is essential, so we felt it important to prioritize the research literature in

which student athletes themselves share their perceptions of Unified Sports participation. Throughout

this paper we use the term “athlete” to refer to students with intellectual disabilities participating in

Unified Sports programs, which is consistent with the language used in Special Olympics Unified Sports

programs.

No identified review has systematically analyzed student athlete reported experiences in

connection to Unified Sports involvement. The purpose of this review was to consider the extant data

reported by school-age students with intellectual disability participating in Unified Sports. Specifically,

we aim to explore the focus of the research capturing athlete Unified Sports experiences and to identify

what athletes report about participation in Unified Sports through the following broad questions:

1. What is the focus of the research capturing athlete experiences with Unified Sports? (stated

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 6

research objective; research questions)

2. What methods have been used to gather athlete experiences? (research and data collection

methods)

3. What do the researchers report about athletes’ experiences participating in Unified Sports?

Methods

To answer these research questions, a convergent systematic mixed studies review was

conducted to synthesize the research on student athlete voice. A mixed methods approach to synthesis

was deemed essential to our aim of uncovering both the focus of existing research studies on student

athlete experiences as well as the various tools and methods that have been used to capture student

experience data. Twelve steps in conducting a systematic mixed studies review (Ferguson et al., 2020)

were followed, with data collected in both quantitative and qualitative forms and analyzed in a

qualitative content and thematic analysis to synthesize the data and answer the research questions

(Clarke, et al., 2019; Stemler, 2000).

Literature Search Procedure

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P)

guided the search procedures and reporting within this review (Moher et al., 2015). First, a search of

academic journals was conducted across nine databases: Academic Search Complete, Academic Search

Premier, CINAHL, ERIC, PsychInfo, PubMed, SAGE, SPORTDiscus and Web of Science Core Collection in

March 2021 using the key terms (“Special Olympics” OR “Unified Champion” OR “Unified Sport”) AND

(athlete OR students OR disability). Second, a hand search was conducted of the reference section of

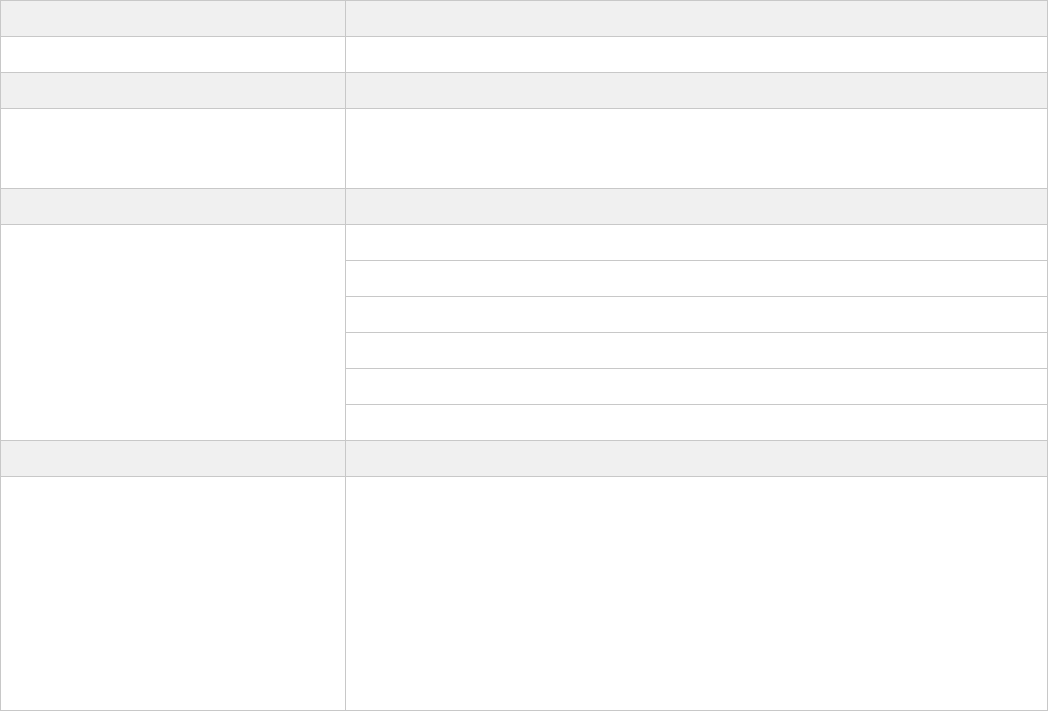

select recent reviews focused on inclusive sports (Grandisson et al., 2019; Scifo et al., 2019). Figure 1

presents a flow chart of the study search process.

<< INSERT FIGURE 1 APPROXIMATELY HERE >>

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 7

For inclusion in this review, articles were required to: (a) be an original study using qualitative,

mixed methods, and/or quantitative methods; (b) focus on Unified Sports defined as an inclusive sports

program in which people with and without intellectual disabilities join together on the same team

(SpecialOlympics.org); (c) include school-age athletes with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities;

and (d) include data reported by athletes participating in Unified Sports that can be parsed out of the

larger sample (if other participants are included such as coaches, parents, typical peers, etc.). To

maintain a focus on student experiences, studies including data not reported by athletes were excluded

(e.g. physical health measurement data). Articles that did not conduct an original study, such as

practitioner pieces, research briefs and articles in which authors mention athletes participating in

Unified Sports but do not elicit original student voice data were also excluded.

Data Extraction and Analysis

A data extraction table was developed with consideration of the study research questions and

Cooper’s (2010) recommended categories for systematic review. Data was extracted from each article in

the eight categories of report characteristics, focus of the study, program details, participants, data

collection, study features, results, and quality appraisal. Three authors read each study and completed

the data extraction independently. The full group of authors then met with discrepancies reviewed and

discussed to 100% agreement.

Analysis of the data from the systematic review used two forms of qualitative analysis: content

analysis and thematic analysis. Qualitative content analysis was used to describe the key study features,

summarizing information on the study samples, data collection methods, and quality indicators

(Stemler, 2000). Then, thematic analysis was used to synthesize the findings across the included studies

related to the study focus and the athlete experiences (Clarke, et al., 2019). Findings sections of the

original articles were extracted, including provided themes and representative athlete quotes, and

analyzed using a thematic analysis process to create initial codes that were then collapsed into themes

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 8

in a collaborative and iterative process. These two qualitative analysis approaches addressed the

systematic review research questions in the present study and allowed for integration across both types

of data and across all the included studies.

Quality Appraisal

The methodological quality of each included study was assessed by three authors using the

systematic review tool QualSyst (Kmet et al., 2004). Qualitative studies were scored using a 10-item

checklist and quantitative studies were scored using a 14-item checklist resulting in a percentage range

of 80% or above indicating strong quality and less than 50% as limited quality (see Table 1). The full

group of authors then met and quality appraisal discrepancies were reviewed and discussed to 100%

agreement.

Results

Database searches resulted in 60 studies after duplicates were removed. After inclusion and

exclusion criteria were applied, 11 articles were identified to include student athlete reported data. Two

additional articles were eliminated during full article coding as data was found to not be specific to

school age athletes (McConkey & Menke, 2020; Pan & Davis, 2019). Nine articles remained for

systematic review, including five qualitative studies: Briere and Siegle (2008); Hassan et al. (2012),

McConkey et al. (2013), McConkey et al. (2019), Wilski et al. (2012), and four quantitative studies: Baran

et al. (2009), Castagno (2011), Elsissy (2013), and Ozer et al. (2012).

Descriptions of Included Studies

Study Quality

Overall study quality was found to be adequate to strong (see Kmet, 2004) with only one study

receiving a limited score likely due to the aim of publication in a practitioner journal (Briere & Siegle,

2008). The quality of the four remaining qualitative studies ranged from 60% (adequate) to 85% (strong)

with researchers consistently reporting research objectives, context/setting, systematic data collection

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 9

procedures, and conclusions supported by results. Partial reporting of study design and theoretical

framework, and absent reporting of potential influence of researcher bias, emerged as patterns across

studies. The quality of the four quantitative studies ranged from 75% (good) to 96% (strong) with all

studies reporting subject selection strategy, analytic methods, some estimate of variance, and details of

outcomes. A noted pattern detracting from quality scores was a lack of reported control for confounding

variables. A frequent partial reporting of participant characteristics emerged along with a need to collect

and report data beyond athlete age (e.g., participant gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, etc.) as

well as a need to include replicable questionnaire/interview content and response options in published

studies.

Study and Sample Characteristics

The reviewed studies were published between 2001 and 2019 and reflected research conducted

across Germany (n=4), Hungary (n=3), Poland (n=3), Serbia (n=3), Ukraine (n=3), USA (n=3), Turkey

(n=2), Egypt (n=1), and India (n=1) with four of the nine studies spanning multiple countries. Three

studies were found to use the same data set (Hassan et al., 2012; McConkey et al., 2013; Wilski et al.,

2012). Overall 289 athletes participating in Special Olympics Unified Sports basketball, football and

soccer were represented across studies. Sample size varied and ranged from 4 to 156 athletes (M=41).

In terms of demographics, 86% of the sample (where reported) was male and athletes were most

commonly reported as high school aged. Only the author groups using the same data set (Hassan et al.,

2012; McConkey et al., 2013; Wilski et al., 2012) provided athlete socioeconomic status, reported as low

when compared to partners. While beyond the scope of this systematic review focused on athlete

experiences, 7/9 studies reported on other participants including a total of 240 partners (players

without intellectual disability) and 65 coaches.

Focus of the Research

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 10

All included studies focused on program evaluation. Studies aimed to identify the impact of

Unified Sports participation on student athletes and to understand related factors. In terms of a

theoretical foundation provided within studies, a literature review of social inclusion and the history of

Special Olympics and Unified Sports emerged as the foundation for research aims (e.g., Castagno, 2001;

Hassan et al., 2012; McConkey et al., 2013; McConkey et al., 2019; Ozer et al., 2012) as well as a review

of foundational research on self-concept (Briere & Siegle 19067; Elsissy, 2013). In relation to social

inclusion, contact theory (Allport, 1958) was identified as undergirding the research of Baran et al.

(2009).

The focus of stated research objectives and/or research questions of each original study specific

to capturing athlete experiences were reviewed and found to group into two overlapping categories: (1)

the impact of Unified Sports on social inclusion, and (2) the impact of Unified Sports on athlete self-

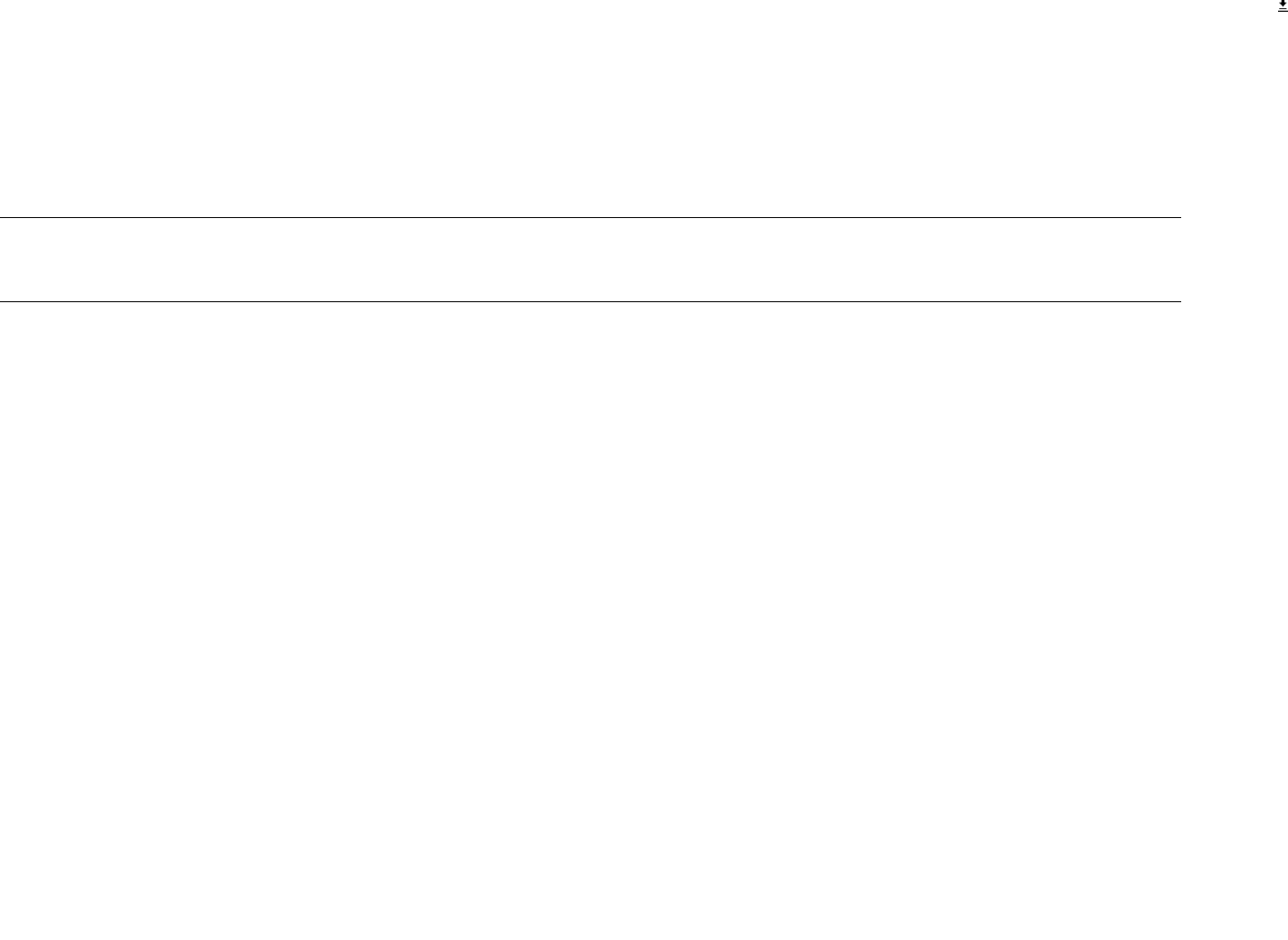

perceptions and personal development. See Table 1.

<< INSERT TABLE 1 APPROXIMATELY HERE>>

Social Inclusion

A primary focus of three qualitative studies reviewed was the impact of Unified Sports to further

athlete social inclusion, for example, to assess the perception of Unified Sports participation to increase

social inclusion opportunities for athletes with intellectual disability. Two articles authored by related

research teams using the same data set focused on Unified Sports organizational factors and how they

were perceived (Hassan et al., 2012; McConkey et al., 2013). The third study (McConkey et al., 2019)

aimed to understand the meaning of social inclusion to Unified Sports participants as well as benefits to

participation and perceived feelings related to inclusion. An overarching goal was to use findings to

inform coaching and Unified Sports policies and procedures.

Athlete Self-Perceptions/ Personal Development

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 11

The second primary focus of studies reviewed was athlete self-perceptions and personal

development. Specific areas explored include self-esteem, physical, social, and global self-concept. In

the article authored by Wilski et al. (2012) reporting on the same qualitative data set used in the Hassan

et al. (2012) and McConkey et al. (2013) studies, the team focused on the impact of Unified Sports

participation on athlete physical, mental and social development. Similarly, Briere and Siegle (2008)

focused on understanding the impact of Unified Sports on athlete physical, social and global self-

concept.

All four quantitative studies reviewed also focused on the impact of Unified Sports on athlete

self-concepts and personal development. For example, Elsissy (2013) compared the impact of Unified

Sports and segregated sports participation on athlete sense of self, and Castagno (2001) considered

changes in self-esteem occurring in athletes with and without intellectual disability participating in

Unified Sports (p. 195). Most commonly, researchers explored athlete social self-concept (Baran et al.,

2009; Briere & Siegle, 2008; Castagno, 2001; Ozer et al., 2012; Wilski et al., 2012), physical self-concept

(Baran et al., 2009; Briere & Siegle, 2008; Elsissy, 2013; Wilski et al., 2012) and global self-concept

(Elsissy, 2013; Ozer et al., 2012).

Data Collection Methods

Two primary data collection methods were identified and used to gather student athlete

experiences: interviews and questionnaires.

Interviews

Athlete interviews were the main method of all five qualitative studies. The data set collected by

Hassan et al. (2012), McConkey et al. (2013) and Wilski et al. (2012) captured athlete experiences

through both one-on-one and group interviews. The research group conducted interviews that were

semi-structured and followed a topic guide with suggested trigger questions. An average of four team

interviews were conducted in each of five countries (N=125 athletes) in addition to 5 individual athlete

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 12

interviews per country (N=25). Interviews were conducted using an informal style with care taken to

elaborate upon the shared responses of each participant (McConkey, 2013). Coding methodology was

reported as interpretative phenomenological analysis (McConkey et al., 2013).

McConkey et al. (2019) conducted eight group interviews with athletes (N=49) using a

structured interview schedule with pictures. First athletes were shown pictures of youth taking part in

activities together (e.g. gathering in a café) and asked structured questions around if a person was being

included or excluded. Next, athletes were shown pictures of Unified Sports participants and asked

similar structured questions. Findings were coded using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) framework for

thematic content analysis. Moreover, Briere and Siegle (2008) conducted one-on-one interviews with

athletes (N=4). No information was provided regarding coding procedures.

Questionnaires

Five questionnaires/ inventories were identified as data collection methods to elicit the self-

perceptions and personal development of athletes: the Friendship Activity Scale (Siperstein, 1980); the

Adjective Checklist (Siperstein, 1980); the Katz-Zigler Self-Esteem Questionnaire (Zigler, 1994); the Piers-

Harris Self-Concept Scale II (Piers, 1969); and the Special Olympics Unified Sports Questionnaire

(Siperstein et al., 2001).

Both the Friendship Activity Scale (Siperstein, 1980), a 10 question Likert inventory of behavior

intention regarding friendship with people with intellectual disability, and the Adjective Checklist

(Siperstein, 1980), a validated inventory with 34 adjectives across four dimensions (affective feelings,

physical appearance, academic appearance and social behavior) were used in two reviewed studies

(Castagno, 2001; Ozer et al., 2012). Reliability estimates for the Friendship Activity Scale were not

provided for the original validity study, but for the Turkish version validation they were reported as

Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86 (Ozer, et al, 2012). For the Adjective Checklist, reliability estimates were

provided as Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81 from the original validation study (Siperstein, 1980) and 0.62 in the

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 13

validation of the Turkish version of the scale (Ozer, et al., 2012). Neither study using these measures

reported reliability estimates for the data they collected. A third validated inventory, the Katz-Zigler Self-

Esteem Questionnaire (Zigler, 1994), was used by Castagno (2001) to measure self-esteem via 12 items

with a yes/no response format. Reliability estimates were provided from the original validation study as

test-retest correlations of 0.75-0.79 and split-half reliability estimates of 0.81-0.85. No reliability

estimates were provided for the data collected using this measure in Castagno (2001).

A measure of self-concept was used in Elsissy (2013) across groups to elicit athlete self-

perception data. The Piers-Harris Self-Concept Scale II (Piers, 1969) is a scale assessing six Domains:

behavioral adjustment, intellectual and school status, physical appearance and attributes, freedom from

anxiety, popularity, and happiness and satisfaction, and was given to both athletes participating in

Unified Sports as well as athletes participating in segregated sports as a comparison. No reliability

estimates were provided for this scale from prior studies or from Elsissy (2013) data collection. Finally,

the Special Olympics Unified Sports Questionnaire (Siperstein et al., 2001) was used by Baran et al.

(2009) to gather information on athlete relationships and self-perceptions. Baran et al. (2009) include a

statement in their Methods that “no reliability or validity estimations have been calculated” (p. 37), and

they do not report estimates in their own results either. Collected data was assessed with

nonparametric measures and included a pre and post Unified Sports participation comparison.

Athlete Reported Experiences

A primary aim of this systematic mixed studies review was to synthesize what student athletes

report as their experiences participating in Unified Sports. Athlete experiences are reported in alignment

with two areas identified as the focus of reviewed studies: (1) social inclusion, and (2) athlete self-

perceptions and personal development.

Athlete Reported Experiences and Social Inclusion

Considering social inclusion as the interaction between the two major life domains of

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 14

community involvement and interpersonal relationships (Simplican, 2015), the research teams of Briere

and Siegel (2008), Hassan et al. (2012), McConkey et al. (2013), McConkey et al. (2019) and Wilski et al.

(2012) report athletes experiencing strengthened social inclusion through Unified Sports participation.

Community Involvement. The reviewed studies indicate that developing an identity as part of a

group or sports team provides meaningful access for athletes to community involvement. Researchers in

multiple studies report athletes valuing the opportunity to join a group within the community, with

themes including ideas of identity and group membership, forming inclusive bonds, recognition in the

community, and benefits of competition and group travel (Briere & Siegel, 2008; Hassan et al., 2012;

McConkey et al., 2013; McConkey et al., 2019; Wilski et al, 2012). Reflecting a desire for community

sports involvement, Hassan et al. (2012) report an athlete as saying, “I like playing sports and I wanted

to be a member of group sports and this is the best way I knew how” (p.9). Suggesting the ability of

Unified Sports to expand community social networks, McConkey et al. (2013) report another athlete as

stating, “When I walk around town ... people say hello to me, people that I did not know before but now

I do because I met them through this team or have played against them in some other competitions” (p.

931).

Through community involvement, researchers report athletes experiencing new found pride in

not only themselves but in their teammates along with a growing feeling of positivity and connectedness

(Hassan et al., 2012; McConkey et al., 2013; McConkey et al., 2019). McConkey et al. (2013), reporting a

theme of Inclusive and Equal Bonds, quote an athlete who shared feelings of connection to their

teammates, “We are all needed on the team, there are no star players, we are a great team and the

team is the star” (p.929). Similarly, McConkey et al. (2019) share an athletes’ strong connection to their

team to represent a theme of Inclusion=Togetherness, “I like being in the group of peers, it’s my life, and

these guys are like my family…” (p.237). The theme of community involvement emerging from the

reviewed studies reflects a common experience shared by athletes. The experience of developing a

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 15

positive identity as a member of a team leading to increased community involvement and feelings of

togetherness.

Interpersonal Relationships. Researchers report athletes’ positive experiences in relation to

community/team involvement result in improved interpersonal relationships and social connections.

Interpersonal relationships were reported by research teams as equality and friendship, sharing

interests, increasing communication with peers, and learning from each other (Briere & Siegel, 2008;

Hassan et al., 2012; McConkey et al., 2013; McConkey et al., 2019; Wilski et al, 2012). Throughout the

literature, researchers spotlight athletes sharing their experiences forming relationships with Unified

Sports partners. Hassan et al. (2012) report growing relationships between athletes and partners over a

Shared Interest in Sports, McConkey et al. (2019) note a theme of Equality emerging among players, and

researchers consistently spotlight increased communication and friendship among players (Briere &

Siegel, 2008; Hassan et al., 2012; McConkey et al., 2013; McConkey et al., 2019; Wilski et al, 2012).

With an emphasis on building interpersonal relationships, McConkey et al. (2013) report upon a

theme of Personal Development of the Athletes and Partners, sharing an athlete quote, “I am not shy to

talk to people. I will hold my head up and speak out loud. I got more used to people in playing on my

team and I am not afraid...” (p. 928), McConkey et al. (2013) provide another example of how

interpersonal relationships among athletes and partners become strengthened over time through a

theme of Inclusive and Equal Bonds,

We all like sport and we ask each other have you seen the game last night, and do you know the

latest results and things like that. Sometimes there is a girl that one of us likes and we talk to

each other about the best way that one of us can ask her out, we share some of that type of

information, personal information with each other. It wasn’t like that from the beginning, but it

is now because we have been playing together for more than a year and we have become good

friends. (p. 929)

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 16

The emergent theme of strengthened interpersonal relationships across studies reflects a

common athlete experience reported by researchers as well as an important finding in relation to social

inclusion. Building on the initial theme of community involvement, it appears the opportunity to engage

in community involvement as part of a Unified Sports team leads to a common athlete experience of

developing strengthened interpersonal relationships.

Barriers to Inclusion. In addition to shared positive social inclusion experiences, researchers

report obstacles to social inclusion, specifically noting program costs (Hassan et al., 2012), as well as

time, location and travel (McConkey et al., 2013; Wilski et al., 2012) as barriers to social inclusion.

Hassan et al. (2012) report a theme of Individual and Programme Financial Costs and suggest finances

needed for participation and related travel emerge as problematic for many athletes. McConkey et al.

(2013) report athletes having limited time as a result of other responsibilities, such as helping their

family after school, as a barrier to social inclusion. An athlete quote shared by McConkey et al. (2013),

“...lots of us live on a different side of the city and it is not so easy for us to hang out after training – we

have to catch a bus or train...that is what makes it difficult” (p. 930), illustrates the location of athletes

as a potential barrier to building social relationships. Of note, while resources of money, time, location

and travel were identified as barriers to inclusion, social obstacles such as attitudes, biases and stigma

within the community were beyond the analyses of included research studies.

Athlete Experiences, Self-Perceptions and Personal Development

In addition to a focus on social inclusion, original studies reviewed focused on athlete

self-perceptions and personal development. Athlete perceptions of personal development from Unified

Sports participation were elicited through quantitative approaches with multiple inventories in relation

to social self-concept, self-esteem, and global self-concept as well as through qualitative interviews (see

Table 1).

Social Self-Concept. Athlete responses to the Friendship Activity Scale (Siperstein, 1980),

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 17

showed increased perceptions of friendship across two different studies. Results of both a pretest-

posttest design study and an experimental-control group comparison suggest significant increases in

athlete perceptions of friendships. Athlete friendship scores significantly increased after participation in

Unified Sports, t(23) = 4.38, p < .01 (Castagno, 2001). Similarly, athletes scores were significantly higher

than peers in a nonparticipating athlete control group (Ozer et al., 2012).

Athlete scores on the Adjective Checklist (Siperstein, 1980), also increased across multiple

studies, representing an increased use of positive adjectives toward people labeled with intellectual

disability. Results of both a pretest-posttest design study and an experimental-control group comparison

suggest increases in athlete perceptions of disability. Athlete scores significantly increased after

participation in Unified Sports, 1(23) = 5.22, p < .01 (Castagno, 2001) in one study. However, an increase

in athlete positive and total adjective scores posttest was not found to be significant (p > .05) in a

second study (Ozer et al., 2012).

Finally, in relation to social self-concept, the Special Olympics Unified Sports Questionnaire

(Siperstein et al., 2001) was used to gather information on athlete relationships and self-perceptions.

Results of a pre and post Unified Sports participation comparison show a significant increase only in

athletes’ willingness to recommend Unified Sports to a friend (p<.05). Of note, however, there was no

significant change in athletes’ reporting of time spent with peers outside of Unified Sports participation

(Baran et al., 2009). In alignment with the inventory results, Briere and Siegle (2008) conclude that

athletes’ reported social self-concept increased through participation in Unified Sports (Briere & Siegle,

2008; Wilsi et al., 2012). However, Wilski et al. (2012) report athletes' increased awareness of social

dynamics may not result in increased social time outside of structured Unified Sports activities. For

example, Wilski et al. (2012) report an athlete’s perception of Unified Sports partners having so much to

do that they have little free time to spend together with peer athletes outside of the program.

Self-Esteem. In addition to increased social confidence, athlete self-esteem was captured as an

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 18

indicator of personal development. Athlete responses to the Katz-Zigler Self-Esteem Questionnaire

(Zigler, 1994) resulted in significant results in a study using a pretest-posttest design. Athletes reported

significantly higher self-esteem after participation in Unified Sports, 1(23) = 4.94, p < .01 (Castagno,

2001). In alignment with the inventory results of Castagno (2001), Wilski et al. (2012) shared athlete

reported perceptions of increased self-esteem elicited through interviews. For example, Wilski et al.

(2012) shared an athlete quote, “I believe in myself, I worked hard to be part of this team, and now I

believe that if I work hard I can achieve many things” to represent the positive impact of Unified Sports

participations on athlete Mental Aspect or growth in positive feelings of self (p. 275).

Global Self-Concept. In terms of global self-concept, a comparison of three groups, Unified

Sports athletes, non-athletes, and athletes participating in segregated sports, Unified Sports athletes

reported significantly higher self-concept. Athlete responses to the Piers-Harris Self-Concept Scale II

(Piers, 1969) show a significant increase in self-concept of Unified Sports athletes across all six domains:

behavioral adjustment, intellectual and school status, physical appearance and attributes, freedom from

anxiety, popularity, and happiness and satisfaction, when compared to a control group not participating

in sports (Elsissy, 2013). Moreover, athlete responses showed a significant increase in self-concept of

Unified Sports athletes in one domain, happiness and satisfaction, when compared to peers

participating in segregated sports (Elsissy, 2013). In contrast to the positive findings reported by Elsissy

(2013), however, Wilski et al. (2012) and Briere and Siegle (2008) shared inconsistent findings in relation

to athlete reported perceptions of global self-concept. Briere and Siegle (2008) identified inconsistent

patterns of athlete physical self-concept as well as inconsistent increases in athlete global self-concept,

with self-concept remaining unchanged for many athletes pre and post Unified Sports participation.

Wilski et al. (2012) reported perceived increases in global self-concept including physical ability across

some athletes but not others, for example in physical skills related to ball play.

Discussion

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 19

This systematic mixed studies review aimed to identify the focus of existing research capturing

athlete experiences in Unified Sports as well as the methods used to collect student experiences, and to

identify what athletes report about their participation in Unified Sports. Unified Sports’ success should

rely heavily on capturing athletes' experiences to better serve them and increase their involvement and

participation, yet throughout our search across nine databases for studies with data reported by school-

age athletes participating in Unified Sports, we found only nine original studies, three of which used the

same dataset, conducted by only six unrelated research groups. Despite the research spanning nine

countries, this reveals an overall dearth of research capturing Unified Sports athletes’ voices which is

surprising as Unified Sports was initiated in 1989. This suggests access to Unified Sports programming

may be limited and/or the experiences of athletes may not be prioritized by researchers. This also

suggests researchers may be relying on other methodologies and participants when studying community

and inclusive sporting.

The focus of the synthesized research was the impact of Unified Sports on social inclusion and

athlete self-perceptions and personal development. This focus supports the wider research on disability

and inclusion and aligns with social justice initiatives to center disability as diversity in inclusion

initiatives across the lifespan (e.g., Shea et al., 2020). While studies synthesized were overall of

appropriate methodological quality, several patterns of need emerged to increase our understanding of

student athletes, specifically the need for research teams to value and capture participant

characteristics beyond age, such as gender, ethnicity and socioeconomic status. It appears that Unified

Sports athletes are primarily male, yet that conclusion stems from only seven of the nine studies

reporting on gender. Beyond a concern as to why more females are not involved in Unified Sports,

provided participant data did not allow for a clear understanding of Unified Sport athlete demographics.

In terms of data collection methods, both qualitative and quantitative methods were used to elicit

athlete experiences with a reliance on quantitative interviews and validated inventories developed

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 20

between 1969 and 1994.

Regarding the impact of Unified Sports participation on social inclusion, athlete experiences

identified via the present review align with previous research reporting that participation in community

sports brings enjoyment of sports to individuals with disabilities (Shogren et al., 2015) previously

without access to team sports. Creating awareness of disability as diversity through sports builds social

inclusion among nations and international groups as was the case in London 2012 where the

Paralympics had a great influence on the attitudes and perspective of non-disabled people to change the

way they think about peers with disabilities (Ferrara et al., 2015). In the studies reviewed, athletes

highly valued the chance of joining a community group and stated it was a positive and proud

experience that enabled them to nurture friendships and build healthier relationships (Hassan et al.,

2012; McConkey et al., 2013; McConkey et al., 2019). Athletes expressed benefits of Unified Sports

participation on community involvement, with multiple athletes sharing positive experiences resulting

from being a member of a team, traveling with a team, and being supported by the larger community in

the role of athlete (Hassan et al., 2012). Athletes also reported developing relationships with

teammates, developing confidence and overcoming shyness (McConkey et al., 2013). In this regard,

sporting activities provide an opportunity to celebrate diversity.

In terms of self-perceptions and personal development, athletes reported increased

perceptions of friendships (Ozer et al., 2012) and self-esteem (Castagno, 2012). These findings align with

previous research reports that participation in Unified Sports may increase athlete self-esteem and

competence through interactions among athletes, coaches and nondisabled partners (Grandisson et al.,

2019). Overall, however, inconsistent results emerged in relation to athlete self-perceptions and

personal development. Multiple research teams reported increased athlete social self-concept

(Castagno, 2001; Ozer et al., 2012) and self-esteem (Castagno, 2001; Wilski et al., 2012). However, Baran

et al. (2009) report no significant increase in athlete reporting of actual time spent with peers outside of

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 21

Unified Sports events and both research teams of Briere and Siegel (2008) and Wilski et al. (2012) report

inconsistent results in athlete global self-concept post Unified Sports participation. This indicates that

additional research is needed to uncover the lasting impact of Unifies Sports participation on athletes’

personal development.

Despite inconsistencies, the findings of multiple researchers support the notion that Unified

Sports increase the self-confidence of the athletes and their social networks (see McConkey et al., 2019).

Participants of Unified Sports showed increased levels of happiness and satisfaction compared to those

who have been playing segregated sports along with better physical abilities (Elsissy, 2013). Unified

Sports also improved people’s perception of intellectual disabilities with study participants using more

positive adjectives to describe people with disabilities after program participation (Castagno, 2001). On

the other hand, we have deduced from the review of the research several obstacles along with the

positive outcomes for athletes to social inclusion. The program's time commitment and costs are two of

the hurdles faced by participants, including the cost of travel. Along with this, athletes also faced a

hurdle due to their residential location as it limited their social interaction with larger groups of Unified

Sports peers. Also emerging for consideration, time spent with peers outside of Unified Sports was not

identified as increasing in any of the related studies (e.g., see Baran et al., 2009). This finding holds

important implications for true community inclusion initiatives.

Recommendations for Social Inclusion

Practical efforts to increase social inclusion outside of Unified Sports participation seem an

important next step for Unified Sports athletes. Further exploration and development of strategies to

promote community inclusion along with Unified Sports include initiatives to increase sports

participation and access and to remove barriers through proactive outreach to targeted groups (Waring

& Mason, 2010). First, existing Unified Sports athlete/ partner sporting opportunities can be expanded

beyond competitive programming. For example, participants of all ability levels can be regularly invited

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 22

to participate in recreational activity groups. Second, participation in mainstream sporting activities with

people of all ability levels interacting together as athletes or fans can be facilitated (Grandisson et al.,

2019). Mainstream participation can be encouraged through outreach to local recreational group

leaders in the community. Third, the importance of social inclusion among local communities, nations

and international groups can be strengthened through continuous collaboration with the disability

community. Inclusive interactions with individuals with intellectual disability leads to increased

understanding of differences and positive attitudes of non-disabled peers.

Limitations

While this systematic mixed studies review provides insight into the extant research literature

on Unified Sports and athlete experiences, it has several limitations. The decision to focus on studies

which reported school-age athlete experiences excluded the voices of older athletes as well as the first-

hand experiences of coaches, peer partners and family members of athletes. These groups may have

meaningful insights to add to the Unified Sports experiences reported by athletes in the present review.

In terms of search methodology, nine databases were used to search for studies to include in the

synthesis. Unpublished studies and theses were not identified and studies that were not in English were

not identified. Given the international scale of Unified Sports, international databases and related

studies may be available that were not captured through our systematic search procedures. Finally, this

review was limited due to the reporting by authors in the original included studies. Participant selection

bias inherent in the original studies, as well as researcher bias due to varied affiliations of original

research groups with Special Olympics Unified Sports, may have impacted the findings of this review.

Recommendations for Research

Special Olympics Unified Sports is a program focused on building the social inclusion of people

with intellectual disability through sports and team participation. Athletes in all studies reviewed

reported positive experiences with Unified Sports leading to increased social inclusion and/or self-

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 23

concepts. The present review identified next steps for research across areas including athlete

characteristics, generalization and maintenance of Unified Sports impact, social barriers to community

inclusion, expanding community sporting opportunities using the Unified Sports model, and expanding

future studies to include measures of athlete self-perceptions beyond inventories used in existing

studies. Specific research questions for exploration stemming from the present findings include: How do

athlete and partner characteristics, including gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, impact

Unified Sports experiences, community inclusion experiences and participant outcomes and needs?

What is the maintenance of athlete personal development gains post Unified Sports participation and do

athletes generalize skills and experiences to other community interactions? How can the Unified Sports

model be applied to community recreational activity groups, programs and events? And, what is the

perspective of external community members regarding Unified Sports athletes and partners including

attitudes of advocacy, strength and understanding as well as biases and stigma that may be pathways

and barriers to expanding community inclusion?

Partnering with the Special Olympics Unified Sports organization, athletes and the wider

disability community is a recommendation for researchers studying the interactions of sports and

community inclusion. Future research valuing Unified Sports athlete experiences, including participatory

research and research conducted by additional research teams, as well as research to facilitate

increased community inclusion of Unified Sports teammates beyond program interactions is suggested

to further social inclusion and awareness of disability as diversity.

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 24

References

References marked with an asterisk (*) indicate studies included in the systematic review.

Allan, V., Smith, B., Côté, J., Ginis, K. A. M., & Latimer-Cheung, A. E. (2018). Narratives of participation

among individuals with physical disabilities: A life-course analysis of athletes' experiences and

development in parasport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 37, 170-178.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.10.004

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

*Baran, F., Top, E., Aktop, A., Özer, D., & Nalbant, S. (2009). Evaluation of a unified football program by

special olympics athletes, partners, parents, and coaches. European Journal of Adapted Physical

Activity, 2(1), 34–45. doi: 10.5507/euj.2009.003

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology,

3(2), 77-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

*Briere, D. E., III, & Siegle, D. (2008). The effects of the unified sports basketball program on special

education students’ self-concepts: Four students’ experiences. TEACHING Exceptional Children

Plus, 5(1).

*Castagno KS. (2001). Special Olympics Unified Sports: changes in male athletes during a basketball

season. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 18(2), 193–206.

https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.18.2.193

Clarke, V., Braun, V., Terry, G & Hayfield N. (2019). Thematic analysis. In Liamputtong, P. (Ed.),

Handbook of research methods in health and social sciences (pp. 843-860). Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_103

Connor, D. J., Gabel, S. L., Gallagher, D. J., & Morton, M. (2008). Disability studies and inclusive

education implications for theory, research, and practice. International Journal of Inclusive

Education, 12(5-6), 441–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802377482

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 25

Dailey, S. L., Alabere, R. O., Michalski, J. E., & Brown, C. I. (2020). Sports experiences as anticipatory

socialization: How does communication in sports help individuals with intellectual disabilities

learn about and adapt to work? Communication Quarterly, 68(5), 499-519.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2020.1821737

*Elsissy, A. (2013). Effects of unified sports program on athlete self- concept. Ovidius University Annals,

Series Physical Education & Sport/Science, Movement & Health, 13, 740–745.

Ferguson, S. L., Kerrigan, M. R., & Hovey, K. A. (2020). Leveraging the opportunities of mixed methods in

research synthesis: Key decisions in systematic mixed studies review methodology. Research

Synthesis Methods, 11(5), 580-593. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1436

Ferrara, K., Burns, J., & Mills, H. (2015). Public attitudes toward people with intellectual disabilities after

viewing olympic or paralympic performance. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 32(1), 19-33.

https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.2014-0136

Grandisson, M., Marcotte, J., Niquette, B., & Milot, É. (2019). Strategies to foster inclusion through

sports: A scoping review. Inclusion, 7(4), 220-233. https://doi.org/10.1352/2326-6988-7.4.220

Hamdani, Y., Yee, T., Oake, M., & McPherson, A. C. (2019). Multi-stakeholder perspectives on perceived

wellness of Special Olympics athletes. Disability and health journal, 12(3), 422-430.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2019.01.009

Harada, C. M., & Siperstein, G. N. (2009). The sport experience of athletes with intellectual disabilities: A

national survey of Special Olympics athletes and their families. Adapted Physical Activity

Quarterly, 26(1), 68-85.

*Hassan, D., Dowling, S., McConkey, R., & Menke, S. (2012). The inclusion of people with intellectual

disabilities in team sports: Lessons from the youth unified sports programme of special

olympics. Sport in Society, 15(9), 1275–1290. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2012.695348

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 26

Haudenhuyse, R. (2017). Introduction to the issue" sport for social inclusion: Questioning policy, practice

and research". Social Inclusion, 5(2), 85-90. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i2.1068

Kmet, L. M., Cook, L. S., & Lee, R. C. (2004). Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary

research papers from a variety of fields. Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, 13

https://doi.org/10.7939/R37M04F16

Kiuppis, F. (2018). Inclusion in sport: Disability and participation. Sport in Society, 21:1, 4-21,

https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2016.1225882

Lopes, J. T. (2015). Adapted surfing as a tool to promote inclusion and rising disability awareness in

Portugal. Journal of Sport for Development, 3(5), 4-10.

*McConkey, R., Dowling, S., Hassan, D., & Menke, S. (2013). Promoting social inclusion through Unified

Sports for youth with intellectual disabilities: a five-nation study. Journal of Intellectual

Disability Research, 57(10), 923–935. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2012.01587.x

*McConkey, R., Peng, C., Merritt, M., & Shellard, A. (2019). The meaning of social inclusion to players

with and without intellectual disability in unified sports teams. Inclusion, 7(4), 234–243.

https://doi.org/10.1352/2326-6988-7.4.234

*McConkey, R., & Menke, S. (2020). The community inclusion of athletes with intellectual disability:

A transnational study of the impact of participating in Special Olympics. Sport in Society, 1-10.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2020.1807515

Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., ... & Stewart, L. A. (2015).

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015

statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

*Özer D, Baran F, Aktop A, Nalbant S, Aglamis E, & Hutzler Y. (2012). Effects of a special olympics unified

sports soccer program on psycho-social attributes of youth with and without intellectual

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 27

disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33(1), 229–239.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2011.09.011

*Pan, C. C., & Davis, R. (2019). Exploring physical self-concept perceptions in athletes with intellectual

disabilities: The participation of Unified Sports experiences. International Journal

of Developmental Disabilities, 65(4), 293-301.

https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2018.1470787

Piers, E. V. (1969) Manual for the Piers-Harris Children's Self-concept Scale. Nashville, TN: Counselor

Recordings & Tescs.

Roswal, M., G. (2007). Special Olympics unified sports: Providing a transition to mainstream

sports. Sobama Journal, 12(1), 13-15.

Schwab, S., Sharma, U., & Loreman, T. (2018). Are we included? Secondary students' perception of

inclusion climate in their schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 75, 31-39.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.05.016

Scifo, L., Chicau Borrego, C., Monteiro, D., Matosic, D., Feka, K., Bianco, A., & Alesi, M. (2019). Sport

intervention programs (SIPs) to improve health and social inclusion in people with intellectual

disabilities: A systematic review. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 4(3), 57.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1029-1

Shea, L.C., Hecker, L. & Lalor, A.R. (2020). From disability to diversity: College success for students with

learning disabilities, ADHD, and autism spectrum disorder. Columbia, SC: University of South

Carolina, National Research Center for the First-Year Experience and Students in Transition.

Shogren, K. A., Gross, J. M., Forber-Pratt, A. J., Francis, G. L., Satter, A. L., Blue-Banning, M., & Hill, C.

(2015). The perspectives of students with and without disabilities on inclusive schools.

Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 40(4), 243-260.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1540796915583493

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 28

Simplican, S. C., Leader, G., Kosciulek, J., & Leahy, M. (2015). Defining social inclusion of people with

intellectual and developmental disabilities: An ecological model of social networks and

community participation. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 38, 18-29.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2014.10.008

Siperstein, G.N., (1980). Instruments for measuring children’s attitudes toward the handicapped.

Unpublished manuscript, University of Massachusetts, Boston.

Siperstein, G.N., & Hardman, M.L. (2001). National evaluation of the special olympics unified sports

Program. Unpublished report. Retrieved June 19, 2021 from

https://media.specialolympics.org/soi/files/sports/unified_sports_report.pdf

Siperstein, G. N., Summerill, L. A., Jacobs, H. E., & Stokes, J. E. (2017). Promoting social inclusion in high

schools using a schoolwide approach. Inclusion, 5(3), 173-188. https://doi.org/10.1352/2326-

6988-5.3.173

Special Olympics Unified Sports (2012). Special olympics unified sports quick reference guide.

Retrieved June 21, 2021 from https://media.specialolympics.org/resources/sports-

essentials/unified-sports/Unified-Sports-Quick-Reference-

Guide.pdf?_ga=2.208898770.114594408.1547142790-79484655.1547142790

Stemler, S. (2000) An overview of content analysis, practical assessment, research, and evaluation, 7,

Article 17. https://doi.org/10.7275/z6fm-2e34

Unified Sports. (2021, April 26). Specialolympics.org. Retrieved June 21, 2021 from

https://www.specialolympics.org/our-work/sports/unified-sports

Special Olympics (n.d.). Unified sports. https://www.specialolympics.org/our-work/sports/unified-

sports

Special Olympics (2019). Annual report. https://annualreport.specialolympics.org/impact

UNIFIED SPORTS, INCLUSION & ATHLETE EXPERIENCES 29

Townsend, M., & Hassall, J. (2007). Mainstream students’ attitudes to possible inclusion in unified

sports with students who have an intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in

Intellectual Disabilities, 20(3), 265-273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2006.00329.x

Waring, A., & Mason, C. (2010). Opening doors: Promoting social inclusion through increased sports

opportunities. Sport in society, 13(3), 517-529. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430431003588192

*Wilski, M., Nadolska, A., Dowling, S., McConkey, R., & Hassan, D. (2012). Personal development of

participants in special olympics unified sports teams. Human Movement, 13(3), 271–279.

https://doi.org/10.2478/v10038-012-0032-3

Zigler, E. (1994). Interim report on individual studies: Self-image, depression, and hopelessness in mildly

retarded adolescents. Unpublished manuscript, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

Records after duplicates removed

(n=60)

X

Figure 1. Study selection flow diagram

Records identified through

database searching

(n=62)

Additional records identified through

other sources (n=2)

Grandisson et al. (2019) ref. list (n=2)

Records included after abstract

and/or methods screening

(n=60)

Records excluded

(n=49)

Data not specific to

Unified Sports and/or

school-age athletes

Records included after full-text article

review

(n=11)

Records excluded

(n=2)

Data limited to health

measures

Total number of studies reviewed

(n=9)

Integration of qualitative and

quantitative studies

Studies containing

qualitative data

(n=5)

Studies containing

quantitative data

(n=4)

Figure Click here to access/download;Figure;3. Figure 1 Flowchart of

search process REVISED.docx

Table 1

Details of Reviewed Studies and Athlete Experiences

Author(s) (year)

& Country

Study

Focus

Athlete

Participants

Program

Sport

Data

Collection

Research Reported Athlete Experiences

with Unified Sports

Research

Quality

QUALITATIVE

Briere & Siegle

(2008)

USA

Athlete self-

concepts &

impact of

Unified Sports

on student

athletes

N=4

High school

students

(3 female,

1 male)

Unified

Basketball

One-on-one

interviews

● Increased social self-concept, e.g., more

popular “with sporty kids” (p.8)

● Consistent or increased global self-

concept, e.g., “you learn a lot” (p.9)

● Scattered physical self-concept, e.g., “a

little better but about the same” (p.7)

40%

Limited

Hassan et al.

(2012)*

Germany,

Hungary,

Poland,

Serbia, Ukraine

Perceptions of

Unified Sports

to further

social inclusion

N=156

12-15 years

81% male

(N=25 in

1:1

interviews)

Unified

Football

and

Basketball

One-on-one

interviews of 25

athletes (5 in each

country) on day of

tournament

● Shared sport interest, e.g., “I like playing

sports and I wanted to be a member of

group sports…” (p.9)

● Unique opportunities, e.g., “Our team is

well known… people recognised me, that

was really a great feeling” (p.10)

● Financial costs, e.g., “…it is money that

stops me” (p.11)

75%

Good

McConkey et al.

(2013)*

Germany,

Hungary,

Poland,

Serbia, Ukraine

Perceptions of

Unified Sports

to further

social inclusion

N=156

12-15 years

81% male

(N=25 in

1:1

interviews)

Unified

Football

and

Basketball

One-on-one

interviews of 25

athletes (5 in each

country) on day of

tournament

● Personal development, e.g., “I am a more

confident person now…I got more used to

people in playing on my team…” (p. 928).

● Inclusive and equal, e.g., “We are all

needed on the team” (p.929).

80%

Strong

Table Click here to access/download;Table;2. Table 1.docx

● Positive perceptions, e.g., “lots of

different people say hello to me” (p. 931).

McConkey et al.

(2019)

Germany, India,

USA

Meaning of

social inclusion

to athletes and

perceptions of

benefits of

participation

N=49

16-25 years

Focus groups (8

group interviews

structured with

photos and

questions)

● Togetherness, e.g., “People with and

without disability just being together,

playing together…” (p.237) (sub-themes:

equality, friendships, participation,

connections, and assistance).

85%

Strong

Wilski et al.

(2012)*

Germany,

Hungary,

Poland,

Serbia, Ukraine

Impact of a

Unified Sport

on participants’

personal

development

(physical,

mental, social)

N=156

12-15 years

81% male

(N=25 in

1:1

interviews)

Unified

Football

and

Basketball

One-on-one

interviews of 25

athletes (5 in each

country) on day of

tournament

● Increased personal development (physical),

e.g., “…my technique is much better, for

example in ball control” (p.273)

● Increased personal development (mental)

e.g., “now I believe that if I work hard I can

achieve many things” (p.275)

● Awareness (social), e.g., “The partners are

very busy” (p.275)

60%

Adequate

QUANTITATIVE

Baran et al.

(2009)

Turkey

Self-

perceptions

and

satisfaction

with Unified

Sports

N=23

12-15 years

100% male

Pre/post Special

Olympics Unified

Sports

questionnaire

(questions on

relationships and

self-perceptions)

● Significant increase in athlete

recommendation of Unified Sports to a

friend (p<.05).

● No significant change in seeing other

athletes when not playing; having social

contact with teammates at home or in the

community.

83%

Strong

Castagno

(2001)

USA

Impact of

Unified Sports

on self-esteem,

N=24

M 13.8

years

Unified

Basketball

Pre/post: The Katz-

Zigler Self-Esteem

Questionnaire

● Significant increase in athlete reported

self-esteem (p<.01); friendships (p<.01);

83%

Strong

attitudes &

friendship

100% male

(Zigler, 1994); The

Adjective Checklist

(Siperstein, 1980);

The Friendship

Activity Scale

(Siperstein, 1980)

and, attitude toward people with

intellectual disability (p<.01).

Elsissy (2013)

Egypt

Impact of

Unified Sports

on self-concept

N=10

M 13.3

years (and

N=15 in

segregated

sports ;

N=15 in

control)

Piers-Harris Self-

Concept Scale II

(Piers, 1952)

● Significant difference between Unified

group and Control group (no sports) in all

Piers-Harris Self-Concept Scale in favor of

Unified group.

● No Significant Difference between Unified

group and Non-Unified group (segregated

sports) in all Piers- Harris Self-Concept

Scale except factor of Happiness and

Satisfaction in favor of Unified.

75%

Good

Ozer et al.

(2012)

Turkey

Impact of

Unified Sports

on

psychosocial

attributes

(friendship,

behavior, social

competence)

N=23

M 14.5

years

100% male

(and N=15

in control

group)

Unified

Soccer

Pre/post: The

Adjective

Checklist

(Siperstein, 1980);

The Friendship

Activity Scale

(Siperstein, 1980)

● Significant increase in athlete reported

friendship activity (p=.003).

● increase in positive and total adjective

scores (attitudes) but not significant (p >

.05).

96%

Strong

Note. * = related articles from the same larger research project.