The Property Tax

Inheritance Exclusion

MAC TAYLOR • LEGISLATIVE ANALYST • OCTOBER 2017

Summary

Ownership Changes Trigger Higher Tax Bills. Under California’s property tax system, the

change in ownership of a property is an important event. When a property changes hands the taxes

paid for the property typically increase—oen substantially. Local government revenues increase in

turn.

Special Rules for Inherited Properties. While most properties’ tax bills go up at the time of

transfer, three decades ago the Legislature and voters created special rules for inherited properties.

ese rules essentially allow children (or grandchildren) to inherit their parent’s (or grandparent’s)

lower property tax bill.

Inheritance Exclusion Benefits Many but Has Drawbacks. e decision to create an inherited

property exclusion has been consequential. Hundreds of thousands of families have received tax

relief under these rules. As a result, local government property tax collections have been reduced by

a few billion dollars per year. Moreover, allowing children to inherit their parents’ lower property

tax bill has exacerbated inequities among owners of similar properties. It also appears to have

encouraged the conversion of some homes from owner-occupied primary residences to rentals and

other uses.

Revisiting the Inheritance Exclusion. In light of these consequences, the Legislature may

want to revisit the inheritance exclusion. We suggest the Legislature consider what goal it wishes

to achieve with this policy. If the goal is to prevent property taxes from making it prohibitively

expensive for a family to continue to own or occupy a property, the existing policy is craed too

broadly and there are options available to better target the benets. Ultimately, however, any

changes to the inheritance exclusion will have to be placed before voters.

SPECIAL RULES FOR INHERITED PROPERTY

Local Governments Levy Property Taxes.

Local governments in California—cities, counties,

schools, and special districts—levy property taxes

on property owners based on the value of their

property. Property taxes are a major revenue source

for local governments, raising nearly $60billion

annually.

Property Taxes Based on Purchase Price.

Each property owner’s annual property tax bill is

equal to the taxable value of their property—or

assessed value—multiplied by their property tax

rate. Property tax rates are capped at 1percent

plus smaller voter-approved rates to nance local

infrastructure. A property’s assessed value is

based on its purchase price. In the year a property

is purchased, it is taxed at its purchase price.

Each year thereaer, the property’s taxable value

increases by 2percent or the rate of ination,

whichever is lower. is process continues until the

property is sold and again is taxed at its purchase

price (typically referred to as the property being

“reassessed”).

Ownership Changes Increase Property Taxes.

In most years, the market value of most properties

grows faster than 2percent. Because of this, most

properties are taxed at a value well below what

they could be sold for. e taxable value of a

typical property in the state is about two-thirds

of its market value. is dierence widens the

longer a home is owned. Property sales therefore

typically trigger an increase in a property’s assessed

value. is, in turn, leads to higher property tax

collections. For properties that have been owned for

many years, this bump in property taxes typically

is substantial.

Special Rules for Inherited Properties. In

general, when a property is transferred to a new

owner, its assessed value is reset to its purchase

price. e Legislature and voters, however, have

created special rules for inherited properties that

essentially allow children (or grandchildren) to

inherit their parent’s (or grandparent’s) lower

taxable property value. In 1986, voters approved

Proposition58—a legislative constitutional

amendment—which excludes certain property

transfers between parents and children from

reassessment. A decade later, Proposition193

extended this exclusion to transfers between

grandparents and grandchildren if the

grandchildren’s parents are deceased. (roughout

this report, we refer to properties transferred

between parents and children or grandparents

and grandchildren as “inherited property.” is

includes properties transferred before and aer the

death of the parent.) ese exclusions apply to all

inherited primary residences, regardless of value.

ey also apply to up to $1million in aggregate

value of all other types of inherited property, such

as second homes or business properties.

2 LegislativeAnalyst’sOfcewww.lao.ca.gov

AN LAO BRIEF

e decision to create an inherited property

exclusion has been consequential. Hundreds of

thousands of families have received tax relief

under these rules. As a result, local government

property tax collections have

been reduced by a few billion

dollars per year. Moreover,

allowing children to inherit

their parents’ lower property

tax bill has exacerbated

inequities among owners of

similar properties. It also

appears to have inuenced

how inherited properties are

being used, encouraging the

conversion of some homes

from owner-occupied primary

residences to rentals or

other uses. We discuss these

consequences in more detail

below.

Many Have Taken

Advantage of

Inheritance Rules

650,000 Inherited

Properties in Past Decade.

Each year, between 60,000 and

80,000 inherited properties

statewide are exempted from

reassessment. As Figure1

shows, this is around

one-tenth of all properties

transferred each year. Over

the past decade, around

650,000 properties—roughly

5percent of all properties in

CONSEQUENCES OF THE INHERITANCE EXCLUSION

the state—have passed between parents and their

children without reassessment. e vast majority of

properties receiving the inheritance exclusion are

single-family homes.

20,000

40,000

60,000

80,000

2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015

4

8

12%

2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 20152014

Steady Use of Inheritance Exclusion Over Past Decade

Total Exclusions

Figure 1

As a Share of All Property Transfers

www.lao.ca.govLegislativeAnalyst’sOfce 3

AN LAO BRIEF

Many Children Receive

Significant Tax Break.

Typically, the longer a home

is owned, the higher the

property tax increase at the

time of a transfer. Many

inherited properties have been

owned for decades. Because

of this, the tax break provided

to children by allowing them

to avoid reassessment oen

is large. e typical home

inherited in Los Angeles

County during the past

decade had been owned by the

parents for nearly 30 years.

For a home owned this long,

the inheritance exclusion

reduces the child’s property

tax bill by $3,000 to $4,000 per year.

Number of Inherited Properties Likely to

Grow. California property owners are getting

older. e share of homeowners over 65 increased

from 24percent in 2005 to 31percent in 2015. is

trend is likely to continue in coming years as baby

boomers—a major demographic group—continue

to age. is could lead to an increasing number

of older homeowners looking to transition their

homes to their children. is, in turn, could result

in an uptick in the use of the inheritance exclusion.

Recent experience supports this expectation. As

Figure2 shows, during the past decade counties

that had more older homeowners also had more

inheritance exclusions. is suggests a relationship

between aging homeowners and inheritance

exclusions which could lead to a rise in inheritance

exclusions as homeowners get older.

Signicant and Growing Fiscal Cost

Reduction in Property Tax Revenues. e

widespread use of the inheritance exclusion has

had a notable eect on property tax revenues. We

estimate that in 2015-16 parent-to-child exclusions

reduced statewide property tax revenues by around

$1.5billion from what they would be in the absence

of the exclusion. is is about 2.5percent of total

statewide property tax revenue. is share is higher

in some counties, such as Mendocino (9percent),

San Luis Obispo (7percent), El Dorado (6percent),

Sonoma (6percent), and Santa Barbara (5percent).

Figure3 reports our estimates of these scal eects

by county.

Greater Losses Likely in Future. It is likely the

scal eect of this exclusion will grow in future years

as California’s homeowners continue to age and the

use of the inheritance exclusion increases. While

the extent of this increase is dicult to predict, if

Counties With More Older Homeowners

Had More Inheritance Exclusions

Inherited Properties as a Share of All Transfers,

California Counties (2010-2014)

Figure 2

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18%

Least Owners Over 65 Most Owners Over 65

Share of Homeowners Over 65

4 LegislativeAnalyst’sOfcewww.lao.ca.gov

AN LAO BRIEF

Amplication of

Taxpayer Inequities

Inequities Among

Similar Taxpayers. Because

a property’s assessed value

greatly depends on how

long ago it was purchased,

signicant dierences arise

among property owners

solely because they purchased

their properties at dierent

times. Substantial dierences

occur even among property

owners of similar ages,

incomes, and wealth. For

example, there is signicant

variation among similar

homeowners in the Bay

Area. Looking at 45 to 55

year old homeowners with

homes worth $650,000 to

$750,000 and incomes of

$80,000 to $100,000 (values

characteristic of the region),

property tax payments in

2015 ranged from less than

$2,000 to over $8,000.

Inheritance Rules

Amplify Inequities.

Inheritance exclusions

exacerbate underlying

taxpayer inequities. is

is because inheritance

exclusions eectively

lengthen the amount of time

a property can go without

being reassessed. To see how

this happens, consider an example of two identical

homes built in the same neighborhood in 1980:

Millions of DollarsShare of Revenue

Fiscal Effects of Inheritance Exclusions

Estimated Reduction in Annual Property Taxes (2015-16)

Figure 3

Sierra

San Benito

Yuba

Kings

Lake

Sutter

Kern

Yolo

Merced

Imperial

Napa

Nevada

Tulare

Butte

Humboldt

Stanislaus

Solano

Mendocino

San Joaquin

Placer

Santa Cruz

Fresno

El Dorado

Riverside

Monterey

Marin

Sacramento

Ventura

San Luis Obispo

Santa Barbara

Sonoma

San Bernardino

Contra Costa

Alameda

San Francisco

San Mateo

Santa Clara

San Diego

Orange

Los Angeles

$250 10

the relationship suggested by Figure2 is true it is

possible that annual property tax losses attributable

to inheritance exclusions could increase by several

hundred million dollars over the next decade.

www.lao.ca.govLegislativeAnalyst’sOfce 5

AN LAO BRIEF

• Home 1 is purchased in 1980 and owned

continuously by the original owners until

their death 50 years later, at which time the

home is inherited by their child.

• Home 2, in contrast, is sold roughly every

15years—around the typical length of

ownership of a home in California.

We trace the property tax bills of these two

homes over several decades in Figure4 under

the assumption that the homes appreciate at

historically typical rates for California homes. By

2030, home1’s bill would be one-third as much

as home2’s bill. In the absence of the inheritance

exclusion, when home1 passes to the original

owner’s child it would be reassessed. is would

erase much of the dierence in property tax

payments between home1 and home2. With the

inheritance exclusion, however, the new owner of

home1 maintains their parent’s lower tax payment.

Over the child’s lifetime, the dierence in tax

payments between home1 and home2 continues

to grow. By 2060 home1’s bill will be one-sixth as

much as home2’s bill.

Unintended Housing Market Eects

Many Inherited Primary Residences

Converted to Other Uses. Inheritance exclusions

appear to be encouraging children to hold on to

their parents’ homes to use as rentals or other

purposes instead of putting them on the for

sale market. A look at inherited homes in Los

Angeles County during the last decade supports

this nding. Figure5 shows the share of homes

that received the homeowner’s exemption—a

tax reduction available only for primary

residences—before and aer inheritance. Before

inheritance, about 70percent of homes claimed

the homeowner’s exemption, compared to about

40percent aer inheritance. is suggests that

many of these homes are being converted from

primary residences to other uses.

It is possible that this trend arises because

people intrinsically make dierent decisions about

inherited property regardless

of their tax treatment. A

closer look at the data from

Los Angeles County, however,

suggests otherwise. Figure6

breaks down the share of

primary residences converted

to other uses by the amount

of tax savings received by the

child. As Figure6 shows, the

share of primary residences

converted to other uses is

highest among those receiving

the most tax savings. A little

over 60percent of children

receiving the highest tax

savings converted their

Home 1

Home 1 Without

Inheritance Exclusion

Home 2

Home 1 is owned continuously by

the same owners until their death

in 2030 and is then inherited by

their child.

Home 2 is sold roughly every

15 years.

Inheritance Exclusion Amplifies Taxpayer Inequities

Property Tax Bill of Two Hypothetical Identical Homes (2016 Dollars)

Figure 4

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

$12,000

1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050 2060

6 LegislativeAnalyst’sOfcewww.lao.ca.gov

AN LAO BRIEF

Inherited Primary Residences

Being Converted to Other Uses

Share of Homes Claiming Homeowner's Exemption

Los Angeles County, 2007-2014

Figure 5

10

20

30

40

50

60

70%

After TransferBefore Transfer

Inherited Homes

Other Home Sales

inherited home to another

use, compared to just under

half of children receiving the

least savings. is suggests

that the tax savings provided

by the inheritance exclusion

may be factoring into the

decision of some children to

convert their parent’s primary

residence to rentals or other

uses.

Contributes to Limited

Availability of Homes for

Sale. e conversion of

inherited properties from

primary residences to other

uses could be exacerbating

challenges for home buyers

created by the state’s tight

housing markets. In many

parts of California, there is a

very limited supply of homes

for sale and buying a home is

highly competitive. Figure7

(see next page) shows that the

inventory of homes for sale

is consistently more limited

in California than the rest

of the country. is limited

inventory—a consequence

of many factors including

too little home building and

an aging population—has

driven up the price of housing

in California and made the

home buying experience

more dicult for many.

When inherited homes are

held o the for sale market,

Higher Tax Savings May Encourage Conversions

Share of Inherited Primary Residences Converted to Other Uses

Los Angeles County, 2006-2016

Figure 6

10

20

30

40

50

60%

Least Savings Most Savings

www.lao.ca.govLegislativeAnalyst’sOfce 7

AN LAO BRIEF

these issues are amplied.

On the ip side, the shi of

inherited homes to the rental

market could put downward

pressure on rents. e data

we reviewed, however, does

not allow us to determine

how many properties are

being converted to rentals as

opposed to other uses—such

as vacation homes. On net,

the shi of homes from

the for-sale market to the

rental market likely results

in fewer Californians being

homeowners and more being

renters.

REVISITING THE INHERITANCE EXCLUSION

It has been decades since Californians voted to

create the inherited property exclusion. Since then,

this decision has had signicant consequences,

yet little attention has been paid to reviewing it.

Moreover, indications are that use of the exclusion

will grow in the future. In light of this, the

Legislature may want to revisit the inheritance

exclusion. As a starting point, the Legislature

would want to consider what goal it wishes to

achieve by having an inheritance exclusion. Is the

goal to ensure that a family continues to occupy a

particular property? Or to maintain ownership of a

particular property within a family? Or to promote

property inheritance in and of itself?

Dierent goals suggest dierent policies. If

the goal is to unconditionally promote property

inheritance, maintaining the existing inheritance

exclusion makes sense. If, however, the goal is more

narrow—such as making sure a family continues

to occupy a particular home—the scope of the

existing inheritance exclusion is far too broad.

Reasons the Existing Policy May Be Too Broad

Property Taxes May Not Be Big Barrier to

Continued Ownership. One potential rationale

for the inheritance exclusion is to prevent property

taxes from making it prohibitively expensive for

a family continue to own a particular property.

e concern may be that if a property is reassessed

at inheritance the beneciary will be unable to

aord the higher property tax payment, forcing

them to sell the property. ere are reasons,

however, to believe that many beneciaries are in

a comparatively good nancial situation to absorb

the costs resulting from reassessment:

• Children of Homeowners Tend to Be

More Afuent. Children of homeowners

tend to be nancially better o as adults.

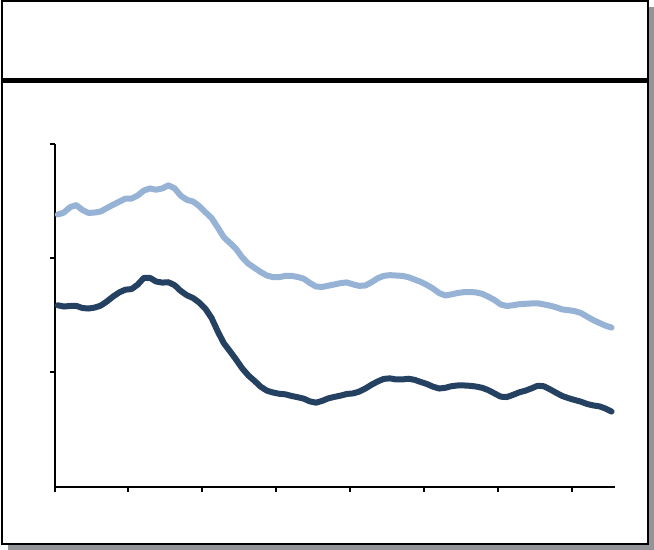

Limited Availability of Homes for Sale in California

Number of Homes for Sale as a Share of All Single Family Homes

Figure 7

California

U.S.

1

2

3%

2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

8 LegislativeAnalyst’sOfcewww.lao.ca.gov

AN LAO BRIEF

Data from the Panel Survey of Income

Dynamics suggests that Californians who

grew up in a home owned by their parents

had a median income over $70,000 in

2015, compared to less than $50,000 for

those whose parents were renters. Beyond

income, several nationwide studies have

found that children of homeowners tend to

be better o as adults in various categories

including educational attainment and

homeownership.

• Many Inherited Properties Have Low

Ownership Costs. In addition to property

taxes homeowners face costs for their

mortgage, insurance, maintenance, and

repairs. ese costs tend to be lower

for properties that have been owned

for many years—as is true of many

inherited properties—largely because their

mortgages have been paid o. According

to American Community Survey data, in

2015 just under 60percent of homes owned

30 years or longer were owned free and

clear, compared to less than a quarter of all

homes. Consequently, monthly ownership

costs for these homeowners were around

$1,000 less than the typical homeowner

($1,650 vs. $670). Because most inherited

homes have been owned for decades,

children typically are receiving a property

with lower ownership costs.

• Property Inheritance Provides Financial

Flexibility. In addition to lower ownership

costs, an additional benet of inheriting

a property without a mortgage is a

signicant increase in borrowing capacity.

Many inherited properties have signicant

equity. is oers beneciaries the option

of accessing cash through nancial

instruments like home equity loans.

Many Children Not Occupying Inherited

Properties. Another potential rationale for the

inheritance exclusion is to ensure the continued

occupancy of a property by a single family. Many

children, however, do not appear to be occupying

their inherited properties. As discussed earlier,

it appears that many inherited homes are being

converted to rentals or other uses. As a result, we

found that in Los Angeles County only a minority

of homes inherited over the last decade are

claiming the homeowner’s exemption. is suggests

that in most cases, the family is not continuing to

occupy the inherited property.

Potential Alternatives

If the Legislature feels the existing policy is

too broad, it has several options to better focus the

exclusion on achieving particular goals. In addition

to better aligning the policy with a particular

objective, narrowing the exclusion would help

to minimize some of the drawbacks discussed

in the prior section. Below are some options the

Legislature could consider. ese options could be

adopted individually or could be combined. Any

changes ultimately would have to be placed before

voters for their approval.

Limit to Homes Used as a Primary Residence.

One option is to limit the exclusion to homes that

are occupied by the family member following

inheritance. Inherited homes used as rentals or

second homes would be subject to reassessment.

Such a change could possibly cut in half the

property tax losses resulting from the existing

exclusion.

Apply Means Testing. Another option is to

require means testing to determine eligibility for

the exclusion. e Legislature could set an income

threshold under which a child’s income would have

to fall to be eligible for the inheritance exclusion.

Phase In Property Tax Increase. A third

option is to phase in over several years the property

www.lao.ca.govLegislativeAnalyst’sOfce 9

AN LAO BRIEF

tax increase resulting from the reassessment of

an inherited property. is change would reduce

the overall nancial benet provided by the

exclusion—in recognition of the relative auence

of many beneciaries—while still providing some

short-term relief. e interim period during which

the increase is phased in could provide the family

member time to make nancial arrangements to

accommodate the ongoing ownership costs of their

inherited property.

CONCLUSION

When a property changes hands the taxes

paid for the property typically increase—oen

substantially. is is not true, however, for

most inherited property. ree decades ago, the

Legislature and voters decided that most inherited

property should be excluded from reassessment.

is has been a consequential decision. Many have

beneted from the tax savings this policy aords.

Nonetheless, the inheritance exclusion raises some

policy concerns about taxpayer equity and adverse

eects on real estate markets.

In light of these consequences, the Legislature

may want to revisit the inheritance exclusion.

We suggest the Legislature consider what goal it

wishes to achieve with this policy. If the goal is to

prevent property taxes from making it prohibitively

expensive for a family to continue to occupy a

home, the existing policy is craed too broadly

and there are options available to better target

the benets. Ultimately, however, any changes to

the inheritance exclusion would have to be placed

before voters.

10 LegislativeAnalyst’sOfcewww.lao.ca.gov

AN LAO BRIEF

www.lao.ca.govLegislativeAnalyst’sOfce 11

AN LAO BRIEF

AN LAO B R I E F

12 LegislativeAnalyst’sOfcewww.lao.ca.gov

LAO Publications

This brief was prepared by Brian Uhler, and reviewed by Jason Sisney. The Legislative Analyst’s Ofce (LAO) is a

nonpartisan ofce that provides scal and policy information and advice to the Legislature.

To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This brief and others, as well as an e-mail subscription service,

are available on the LAO’s website at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000,

Sacramento, CA 95814.